Encountering the Environment: Rural Communities in England, 1086-1348

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hereward and the Barony of Bourne File:///C:/Edrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/Hereward.Htm

hereward and the Barony of Bourne file:///C:/EDrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/hereward.htm Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 29 (1994), 7-10. Hereward 'the Wake' and the Barony of Bourne: a Reassessment of a Fenland Legend [1] Hereward, generally known as 'the Wake', is second only to Robin Hood in the pantheon of English heroes. From at least the early twelfth century his deeds were celebrated in Anglo-Norman aristocratic circles, and he was no doubt the subject of many a popular tale and song from an early period. [2] But throughout the Middle Ages Hereward's fame was local, being confined to the East Midlands and East Anglia. [3] It was only in the nineteenth century that the rebel became a truly national icon with the publication of Charles Kingsley novel Hereward the Wake .[4] The transformation was particularly Victorian: Hereward is portrayed as a prototype John Bull, a champion of the English nation. The assessment of historians has generally been more sober. Racial overtones have persisted in many accounts, but it has been tacitly accepted that Hereward expressed the fears and frustrations of a landed community under threat. Paradoxically, however, in the light of the nature of that community, the high social standing that the tradition has accorded him has been denied. [5] The earliest recorded notice of Hereward is the almost contemporary annal for 1071 in the D version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Northern recension probably produced at York,[6] its account of the events in the fenland are terse. It records the plunder of Peterborough in 1070 'by the men that Bishop Æthelric [late of Durham] had excommunicated because they had taken there all that he had', and the rebellion of Earls Edwin and Morcar in the following year. -

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

Just Dogs Live, East of England Showground, Peterborough, Pe2 6Xe

Present British Flyball Association 48 Team LIMITED OPEN SANCTIONED TOURNAMENT at JUST DOGS LIVE, EAST OF ENGLAND SHOWGROUND, PETERBOROUGH, PE2 6XE on Saturday 10th and Sunday 11th July 2010 Closing date for entries: 10th June 2010 For further information contact: Ellen Schofield Telephone: 01353 659950 / 07725 904831 Address: 43 Briars End, Witchford, Ely, Cambs, CB6 2GB E-mail: [email protected] This tournament is being held alongside the Just Dogs Live Event on the 9th/10th/11th July 2010. Just Dogs Live incorporates the East of England Championship Dog Show and will include the traditional Crufts qualifier showing classes. The show, now in its second year, will also feature additional attractions, including demonstrations and competitions to ensure the event is a fantastic day out for all dog lovers, young and old. Just a selection of the demos, have-a-gos and competitions that are happening are… Laines Shooting School & Mullenscote Gundogs Essex Dog Display Team Canine Partners Pets As Therapy Prison Dog Display Scurry Bandits For more information please see their website - http://www.justdogslive.co.uk/ The area of the showground that is covered by the BFA sanctioned tournament is not part of UK Kennel Club Licensed show, and you are free to come and go within this area as you please. If you wish to visit the main show you are also free to do so, and we will supply you with wrist bands to enable you to enter the show FOC. However, if you wish to take your dog into the KC area of the showground, you will be required to sign a declaration form in accordance with the KC rules. -

Castor Village – Overview 1066 to 2000

Chapter 5 Castor Village – Overview 1066 to 2000 Introduction One of the earliest recorded descriptions of Castor as a village is by a travelling historian, William Camden who, in 1612, wrote: ‘The Avon or Nen river, running under a beautiful bridge at Walmesford (Wansford), passes by Durobrivae, a very ancient city, called in Saxon Dormancaster, took up a great deal of ground on each side of the river in both counties. For the little village of Castor which stands one mile from the river, seems to have been part of it, by the inlaid chequered pavements found there. And doubtless it was a place of more than ordinary note; in the adjoining fields (which instead of Dormanton they call Normangate) such quantities of Roman coins are thrown up you would think they had been sewn. Ermine Street, known as the forty foot way or The Way of St Kyneburgha, now known as Lady Connyburrow’s Way must have been up towards Water Newton, if one may judge from, it seems to have been paved with a sort of cubical bricks and tiles.’ [1] By Camden’s time, Castor was a village made up of a collection of tenant farms and cottages, remaining much the same until the time of the Second World War. The village had developed out of the late Saxon village of the time of the Domesday Book, that village having itself grown up among the ruins of the extensive Roman villa and estate that preceded it. The pre-conquest (1066) settlement of Castor is described in earlier chapters. -

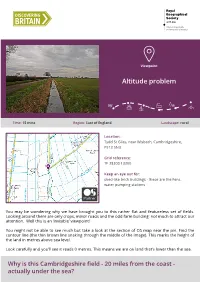

Altitude Problem

Viewpoint Altitude problem Time: 15 mins Region: East of England Landscape: rural Location: Tydd St Giles, near Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, PE13 5NU Grid reference: TF 38300 13300 Keep an eye out for: shed-like brick buildings - these are the Fens water pumping stations You may be wondering why we have brought you to this rather flat and featureless set of fields. Looking around there are only crops, minor roads and the odd farm building: not much to attract our attention. Well this is an ‘invisible’ viewpoint! You might not be able to see much but take a look at the section of OS map near the pin. Find the contour line (the thin brown line snaking through the middle of the image). This marks the height of the land in metres above sea level. Look carefully and you’ll see it reads 0 metres. This means we are on land that’s lower than the sea. Why is this Cambridgeshire field - 20 miles from the coast - actually under the sea? The answer is all around. Look for the long straight channels across the fields. In wet weather they are full of water. These are not natural rivers but artificial ditches, dug to drain water off the fields. So much water was drained away here that the soil dried out and shrank. This lowered the land so much that in places it is now below sea-level! But why was the land drained here and how? Originally the expanse of low-lying land from Cambridge through The Wash and up into Lincolnshire was inhospitable. -

Alwalton Hall, Alwalton, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire

ALWALTON HALL, ALWALTON, PETERBOROUGH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE ALWALTON HALL CHURCH STREET, ALWALTON, PETERBOROUGH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE An impressive village house believed to have been built for the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam; this Grade II listed property has beautiful proportions and is accompanied by mature gardens, former paddock land and stables extending in all, to approximately 4.05 acres. APPROXIMATE MILEAGES: A1 dual carriageway 0.4 miles • Peterborough train station 5 miles • Stamford 11 miles • Huntingdon train station 17 miles ACCOMMODATION IN BRIEF: Entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, dining room, TV room, kitchen, breakfast room, snooker room, office, study, utility, inner hall, extensive cellars and stores. Master bedroom with separate dressing room and ensuite bathroom, guest suite with dressing area and shower room, 7 further bedrooms and 3 further shower rooms. Swimming pool, Jacuzzi, pool room with changing rooms, bar and WCs, plant room, house boiler room, gardener’s WC, hobbies room and gym, stores, garaging for up to 4 cars, 3 stables and a tack room. Beautifully maintained gardens to the front and rear of the house extending to an immaculately kept former paddock edged with a conifer shelter belt. In all the property extends to approximately 4.05 acres (1.64 ha). Stamford office London office 9 High Street 17-18 Old Bond Street St. Martins London W1S 4PT Stamford PE9 2LF t 01780 484696 [email protected] SITUATION Alwalton lies to the west of the Cathedral city of Peterborough and to the east of the A1 dual carriageway, which is easily accessible. Th e village benefits from a Church, a public house serving food (Th e Cuckoo), a post office/village shop and a village hall. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

Download (11MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] "THE TRIBE OF DAN": The New Connexion of General Baptists 1770 -1891 A study in the transition from revival movement to established denomination. A Dissertation Presented to Glasgow University Faculty of Divinity In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Frank W . Rinaldi 1996 ProQuest Number: 10392300 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10392300 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. -

Farcet Farms Yaxley Fen, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire PE7 3HY an Outstanding Farm with Grade 1 Land Capable of Growing Root Crops, Field Vegetables and Cereals

Farcet Farms, Cambridgeshire Farcet Farms Yaxley Fen, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire PE7 3HY An outstanding farm with grade 1 land capable of growing root crops, field vegetables and cereals Peterborough 4 miles, Huntingdon 21 miles, A1(M) J16 4 miles Mainly grade 1 land over three farms | Irrigation licences for about 224,258m3 of water Refrigerated stores for 1,400t onions | Insulated storage for 500t onions | 1,650t grain storage A two bedroom dwelling and planning consent for a further dwelling | Two solar PV schemes About 1,265.26 acres (512.06 ha) in total For sale as a whole or in up to three lots Lot 1 – Yaxley Fen Farm About 481.88 acres (194.58 ha) Grade 1 land | Four sets of farm buildings 350 Tonne grain store | Two bedroom dwelling and planning application for a further dwelling Summer abstraction licence | Solar PV Lot 2 – Holme Road Farm About 521.45 acres (211.06 ha) Grade 1 and 3 land | 70,000m3 irrigation reservoir with ring main Lot 3 – Black Bush Farm About 262.93 acres (106.42 ha) Grade 1 and 2 land | Refrigerated stores for 1,400 tonnes onions | Further storage for 500 tonnes onions with drying floor | 1,300 tonne grain store | 50,000m3 irrigation reservoir with ring main | Solar PV 500000 600000 East Region 1:250 000 Series Agricultural Land Classification This map represents a generalised pattern of land classification grades and any enlargement of the scale of the map would be misleading. This map does not show subdivisions of Grade 3 which are normally mapped by more detailed survey work. -

ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Her Mon Mæg Giet Gesion Hiora Swæð

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Her mon mæg giet gesion hiora swæð EXECUTIVE EDITORS Simon Keynes, Rosalind Love and Andy Orchard Editorial Assistant Dr Brittany Schorn ([email protected]) ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD Professor Robert Bjork, Arizona State University, Tempe AZ 85287-4402, USA Professor John Blair, The Queen’s College, Oxford OX1 4AW, UK Professor Mary Clayton, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland Dr Richard Dance, St Catharine’s College, Cambridge CB2 1RL, UK Professor Roberta Frank, Dept of English, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA Professor Richard Gameson, Dept of History, Durham University, Durham DH1 3EX, UK Professor Helmut Gneuss, Universität München, Germany Professor Simon Keynes, Trinity College, Cambridge CB2 1TQ, UK Professor Michael Lapidge, Clare College, Cambridge CB2 1TL, UK Professor Patrizia Lendinara, Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione, Palermo, Italy Dr Rosalind Love, Robinson College, Cambridge CB3 9AN, UK Dr Rory Naismith, Clare College, Cambridge CB2 1TL, UK Professor Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, University of California, Berkeley, USA Professor Andrew Orchard, Pembroke College, Oxford OX1 1DW, UK Professor Paul G. Remley, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-4330, USA Professor Paul E. Szarmach, Medieval Academy of America, Cambridge MA 02138, USA PRODUCTION TEAM AT THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Sarah Westlake (Production Editor, Journals) <[email protected]> Daniel Pearce (Commissioning Editor) <[email protected]> Cambridge University Press, Edinburgh Building, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge CB2 8BS Clare Orchard (copyeditor) < [email protected]> Dr Debby Banham (proofreader) <[email protected]> CONTACTING MEMBERS OF THE EDITORIAL BOARD If in need of guidance whilst preparing a contribution, prospective contributors may wish to make contact with an editor whose area of interest and expertise is close to their own. -

East of England Agricultural Society Annual Report and Accounts 2017

Julian Proctor OBE President East of England Agricultural Society Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Education and Opportunities Sandra Lauridsen (Education Manager) and Tom Arthey (Marshal Papworth Chairman) with 15 short course and MSc Marshal Papworth students. Food and Farming Day drew 6,000 children from 69 schools to learn about food, farming and rural life. A huge thank you to 510 exhibitors, 109 businesses and over 100 volunteers who made it possible. Cultiv8, our group for young rural professionals held 9 meetings in the year with a focus on agricultural knowledge transfer and personal development. In Breakfast Week, we visited schools to educate over 400 children on the importance of a healthy breakfast and how to make one. Financial statements East of England Agricultural Society (A Company Limited by Guarantee) For the period ended 31 December 2017 Company No. 1589922 Registered Charity No. 283564 East of England Agricultural Society (a company limited by guarantee) 2 Financial statements for the period ended 31 December 2017 Company information Constitution: East of England Agricultural Society is a company limited by guarantee and a charity governed by its Memorandum and Articles of Association, incorporated on 7 October 1981 in England, with the last amendment on 19 March 2013 Charity registration 283564 number: Company 1589922 registration number: Registered office: East of England Showground Peterborough PE2 6XE Email: [email protected] Web: www.eastofengland.org.uk Directors at the T B W Beazley Chairman date the -

Huntingdonshire. [Kelly's

74 STANGROUND. HUNTINGDONSHIRE. [KELLY'S 1538, but is imperfect. The living is a vicarage, net destroyed by fire in 1899· Edward Westwood esq. yearly value £4oo, including 2I4 acres of glebe, with is lord of the manor. The principal landowners are residence, in the gift of the Master and Fellows of Em- Lieut.-Col. Charles I sham Strong J .P. the Corporatirm manuel College, Cambridge, and held since 1905 by the of Peterborough and the vicar. In the vicarage garden Rev. Edmund Gill Swain M.A. and formerly scholar of is an ancient cross, 5ft. 2in. in height, discovered on that college. The chapelry of Farcet was formerly an- the Farcet road, where, till 1865, it formed a bridge nexed to this living, but by Order in Council, 27th over a ditch. The soil is a rich loam; subsoil, clay February, 1885, the parishes are now separated. The and gravel. The chief crops are wheat, barley and Baptists and Primitive Methodists have places of war- beans. The area of South Stanground civil parish is ship here. The Cemetery, opened in IB9o, is under the I,279 acres of land and 8 of water; rateable value, control of a Joint Burial Committee of 6 members. £7,6I3; the population in 191I was 1,3-92. The popu Charities :-Edward Bellamy, in r657, left a rent-charge lation of Stanground ecclesiastical parish, which of £3 yearly to apprentice one boy alternately in this extends into the Isle of Ely, is 1,463. parish and Farcet: William Bellamy, in I704, and Robert Sexton, Arthur Seaward.