From the Front Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Registered Ngos

LIST OF REGISTERED NGOS Name of the NGO Cause Website Contact Details FCRA Able Disabled All ADAPT endeavours to provide equal opportunities to disabled people People especially in the field of education and employment. The society also Dr.Anita Prabhu Together(Formerly conducts awareness programs about rights of the disabled, provides www.adaptssi.org 9820588314 Yes The Spastics therapy services to them and empowers mothers of disabled children [email protected] Society of India) by providing education and training for income generation. Amcha Ghar, a home for girls is dedicated to helpless female children - irrespective of their religion or caste- who are susceptible to the Susheela Singh vulnerable conditions of living on the street. The home aims to educate Amcha Ghar www.amchaghar.org 9892270729 Yes the girls in an English medium school, to train and transform them into amchaghar2yahoo.com skilled adult women who are able to live an independent life in the main stream of society. AAA aims to be the premier non-profit global body that represents & promotes the interests of individuals who have studied in the United Yasmin Shaikh States of America & those who wish to study in the United States of American Alumni 9987156303 America. It provides thought leadership in the area of educational, www.americanalumni.net Association american.alumni.association cultural and economic ties between India and the U.S. It includes many @gmail.com prominent members from the Indian Industries, Trade and Commerce and Multinational companies. An independent registered trust in India that provides immediate Chadrakant Deshpande AmeriCares India response to emergency medical needs and supports long-term www.americaresindia.org 9920692629 Foundation humanitarian assistance programs in India and in neighbouring [email protected] countries, irrespective of race, creed or political persuasion. -

April + Miscellaneous

April + Miscellaneous NATIONAL Goa State Government has decided to launch its own app-based taxi service at some key tourist destinations across the state. World-class Interpretation Centre and tourist facilities was inaugurated at Konark Sun Temple at Konark, which coincides with Utkal Divas celebrationsin Od A ten-member committee headed by the I&B Secretary is to regulate digital broadcasting & online news portal Election Commission will set up 'Pink' polling booths, for the first time in Karnataka, for the May 12 election to the Legislative Assembly. ‘Hamar Haathi, Hamar Saathi’: Jharkhand starts elephant bulletin on radio to check man-animal conflict. The special bulletin, which will be aired twice daily — at 8.30am and 4.30pm, informed listeners about the locations where herds of elephants have been spotted and the direction in which they might be headed. Know more Jharkhand along with Chhattisgarh and Odisha is home to 10% of the country’s elephant population, and account for approximately 65% of human casualties in conflicts with wild herds or stray bulls Jammu's gets its first tulip garden at Sanasar is attracting nature enthusiasts from all over the country. Sikkim announced monthly pension for farmers engaged in organic farming in the state. Sikkim is the first fully organic state in the country. © Clat Possible. All rights reserved. Unauthorized copying, sale, distribution or circulation of any of the contents of this work is a punishable offence under the laws of India. www.clatpossible.com A Team Satyam Offering April + Miscellaneous The UIDAI has brought in secure digitally-signed QR Code on e-Aadhaar that will now contain photograph of the Aadhaar holder too, in addition to demographic details, to facilitate better offline verification of an individual. -

A Study on Rights of Lgbt and Transgender Community – Human Rights Perspective Tarunika.J Iii Year Bba.Llb, Saveetha School of Law, Saveetha University

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 04 Issue 10 September 2017 A Study On Rights Of Lgbt And Transgender Community – Human Rights Perspective Tarunika.J Iii Year Bba.Llb, Saveetha School Of Law, Saveetha University. INTRODUCTION: At first there are some basic terminologies passed after the support of all political which are to be known before going into this parties in Rajya sabha. It gave rights akin concept. Basically the word ‘sex’ is the SC/ST’s who get enrolled in the schools something which is a cursory examination and jobs in government which is a perfect that is assigned by birth. The word ‘gender’ way to protect then against sexual abuse. is the one that reflects the social or cultural But at recent times there is a conflict that the difference rather than biological reflection, transgender who were given the identity of which in simple words can be said as state third gender are been sent for of being male or female. The other term reconsideration. ‘sexual orientation’ is the feeling of Though there are some negatives, the emotional or sexual attraction for others. government has made Sec 377 of Indian The Constitution of India has given the right Penal Code as unconstitutional. The Chapter to life and personal liberty in Article 21 as a XVI of the Indian Penal Code which deals fundamental right conferred to all people about Offences affecting human body in within the territory of India. And by this it which section 377 of Indian Penal Code can be said that even the people belonging to deals with unnatural offences which defines transgender and the LGBT community shall unnatural offences as “whoever voluntarily exercise this birth right. -

Stepping up ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019

Stepping Up ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 Annual Report 2018-2019 1 Images © Parveen Lamabam, Pranab K. Aich and Prashant Panjar for Alliance India Unless otherwise stated, the appearance of individuals in this publication gives no indication of their HIV status. Design by Sunil Butola Published: December 2019 © Alliance India Information contained in the publication may be freely reproduced, published or otherwise used for non-profit purposes without permission from Alliance India. However, Alliance India requests to be cited as the source of the information. Recommended Citation: Alliance India, Stepping Up, Annual Report 2018-2019, New Delhi India HIV/AIDS Alliance 6 Community Centre, Zamrudpur Kailash Colony Extension New Delhi 110048 T +91-11-4536-7700 [email protected] Follow Alliance India on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/indiahivaidsalliance Stepping Up ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 Annual Report 2018-2019 3 Message from the Chief Executive I have been very fortunate to be a bigger part of Alliance India’s 20 years of journey. Alliance India did not take a long time from being a dependent local partner to becoming a fully independent and credible national organization, because the community most affected by HIV was always in the center of all initiatives that Alliance India has taken. We have three key parameters through which we pass our decisions, we amplify community voices; we fast track newer methods and technologies for improving quality of lives of most marginalised people – men who have sex with men, transgender, people who use drugs, women in sex work, people living with HIV and young people in all the above categories; and we supplement and complement the national programme in partnership with government and other stakeholders. -

Geographies of Health and Development

GEOGRAPHIES OF HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT Geographies of Health Series Editors Allison Williams, Associate Professor, School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, Canada Susan Elliott, Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Management and School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Canada There is growing interest in the geographies of health and a continued interest in what has more traditionally been labeled medical geography. The traditional focus of ‘medical geography’ on areas such as disease ecology, health service provision and disease mapping (all of which continue to reflect a mainly quantitative approach to inquiry) has evolved to a focus on a broader, theoretically informed epistemology of health geographies in an expanded international reach. As a result, we now find this subdiscipline characterized by a strongly theoretically-informed research agenda, embracing a range of methods (quantitative; qualitative and the integration of the two) of inquiry concerned with questions of: risk; representation and meaning; inequality and power; culture and difference, among others. Health mapping and modeling has simultaneously been strengthened by the technical advances made in multilevel modeling, advanced spatial analytic methods and GIS, while further engaging in questions related to health inequalities, population health and environmental degradation. This series publishes superior quality research monographs and edited collections representing contemporary applications in the field; this encompasses original research as well as advances in methods, techniques and theories. The Geographies of Health series will capture the interest of a broad body of scholars, within the social sciences, the health sciences and beyond. Also in the series Soundscapes of Wellbeing in Popular Music Gavin J. -

Language, Literature and Culture of Western Odisha Tila Kumar

SOCIAL TRENDS1 Journal of the Department of Sociology of North Bengal University Vol. 5, 31 March 2018; ISSN: 2348-6538 UGC Approved Social Relationships Through Feminist Lens Jhuma Chakraborty Abstract: This paper endeavours to discuss two real life relationships from the perspective of two philosophers- Carol Gilligan, a renowned psychologist and philosopher and Simone de Beauvoir an existentialist philosopher. I will show how the readings of these relations become difficult from the perspectives of two philosophies. Both of them have critiqued the patriarchal top down structure like any other feminist and have explored and interpreted human relations from novel perspectives. Gilligan maintains that human beings are essentially related. Gilligan suggests that the entire relational network of a society can be sustained through care and empathetic listening of the voices of the ‘Other’. Beauvoir is an existentialist philosopher who maintains that human existence creates his/her being through freedom. One should go beyond the constraints of our contingent existence and give meaning to everyday relations through a never-ending venture of taking new projects. Keywords: Relational self, voice, empathetic listening, freedom, facticity. Introduction My paper focuses on two stories and their interpretation from feminist perspective. I am concerned with the ethical aspect of the two happenings. I want to discuss them from feminist perspective simply because patriarchal values will not appreciate the moral dilemma involved in these two stories. These are real life stories and are not a product of my imagination. The names of the characters are the only changes that I have made and the rest has been a description of what actually occurred. -

LGBT Movement in India Hena Khatun Research Scholar, Deptt

SOCIAL TRENDS217 Journal of the Department of Sociology of North Bengal University Vol. 5, 31 March 2018; ISSN: 2348-6538 UGC Approved LGBT Movement in India Hena Khatun Research Scholar, Deptt. of Humanities and Social Sciences IIT (1SM) Dhanbad Abstract: Although sexual diversity was prominent in ancient India, heterosexuality has become the norm of present times. People with different sexual orientation other than heterosexuality are subjected to various forms of violence and are made to live on the margin of society. This paper, which is based on existing literatures and newspaper articles, aims at first to discuss the diverse sexual past of Indian society and how with the advent of colonial rule, heterosexuality became the dominant and only ‘accepted’ form of sexuality. It also aims at discussing the trajectory of LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual and Transgender) movement in India and the role of various NGOs and other organization in it. At last there are some suggestions regarding social acceptability of sexual diversity which if comes along with legal safeguards, would create a better society. Keywords: Sexuality, section 377 (Indian Penal Code-IPC), LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual and Transgender). Introduction LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) is the initialism generally used to refer to the people with diverse sexual orientation and gender identity. It is problematic to bring all diverse sexualities and gender identities under one umbrella term and therefore many other abbreviations such as I (Intersexes), Q (Queer) are being added day by day to the initialism LGBT. Sexual diversity is the integral part of human history; there have always been people with homosexual (sexual orientation towards same sex), bisexual (sexual orientation towards both same and opposite sex) orientation and diverse gender identity (transgender, cross-dresser etc). -

Mapping Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks in South Asia REPORT

APCOM Report No. 2, July 2008 South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks Mapping Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks in South Asia REPORT No. 2, July 2008 © 2008 APCOM. All rights reserved. South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks APCOM Report No. 2, July 2008 South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks Acknowledgments This study, undertaken by SAATHI’s Calcutta office, and commissioned by APCOM, was conducted with financial support from UNAIDS, as part of their ongoing support to APCOM. We are grateful to both UNAIDS and SAATHII for their support and contribution. APCOM Report No. 2, July 2008 South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks APCOM Report No. 2, July 2008 South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks The Asia Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual Health (APCOM) is a regional coalition of MSM and HIV community-based organisations and networks, the government sector, donors, technical experts and the UN system. The main purpose is advocating for political support and increases in investment and coverage of HIV services for males who have sex with males (MSM) and transgenders in Asia and the Pacific. APCOM promotes the principles of good practice and lessons learnt by bringing together representatives from diverse groups in an effort to share experience, knowledge and expertise. The APCOM website includes additional resource materials including this Report, Policy Briefs, Commentaries, reports, news stories and APCOM membership registration. For more information, please visit www.msmasia.org. APCOM Report No. 2, July 2008 South Asian Transgender Groups, Organisations and Networks Defining the term transgender in the context of South Asia Broadly speaking, transgender people are individuals whose gender expression and/or gender identity differs from conven- tional expectations based on the biological sex they were born into. -

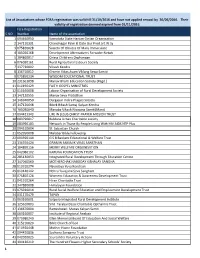

S.NO Fcra Registration Number Name of the Association 1 094640050

List of Associations whose FCRA registration was valid till 31/10/2016 and have not applied renwal by 30/06/2016. Their validity of registration deemed expired from 01/11/2016. Fcra Registration S.NO Number Name of the association 1 094640050 Karnataka State Harijan Girijan Organisation 2 147110331 Chandnagar Palm & Date Gur Prod.art.W.Sy 3 075820028 Society Of Oblates Of Mary Immaculate 4 105020168 Development Alternativers Forwider Netwk 5 104860017 Orissa Childrens Orphanage 6 076030161 Rural Agricultural Labours Society 7 337730002 Vikash Kendra 8 136710012 Gramin Vikas Avam Viklang Sewa Samiti 9 075850234 WISDOM EDUCATIONAL TRUST 10 231661098 Manav Bharti Education Society (Regd.) 11 010190429 FAITH GOSPEL MINISTRIES 12 010160008 Labour Organisation of Rural Development Society 13 147120555 Manav Seva Pratisthan 14 146940050 Durgapur Indira Pragati Society 15 147120648 Bibek Bikash Samaj Kalyan Kendra 16 105030040 Manaba Vikash Niyajana Samiti(Mani) 17 094421343 LIFE IN JESUS CHRIST PRAYER MISSION TRUST 18 083790017 Buldana Urban Charitable society 19 083990183 Network in Thane By People Living With HIV AIDS NTP Plus 20 094510004 St. Sebastian Church 21 052950008 Malabar Bible Fellowship 22 094590144 G S B Bankers Educational & Welfare Trust 23 136550424 GRAMIN SAMAJIK VIKAS SANSTHAN 24 104890156 MERRY WELFARE ORGANISATION 25 042080102 KARUNA FOUNDATION TRUST 26 285130053 Integrated Rural Development Through Education Centre 27 147040560 MOTHERCHAK NABODAY KISHALAY SANGHA 28 010310274 Navodaya Yuva Kendram 29 010140142 Nehru Yuvajana Seva Sangham 30 075850126 Womens Education & Awareness Development Trust 31 041910264 Hiran Charitable Trust 32 347880008 Himalayan Foundation 33 075920014 Rural Social Welfare Education and Emploument Development Trust 34 031170479 TAPAN 35 063160001 Satpura Integrated Rural Development Institute 36 125610003 Smt. -

Annual Report 2018-19.Pdf

1 Hon'ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi delivering his address for Mann Ki Baat 2 Annual Report 2018-19 3 CONTENTS Highlights of the Year ..................................................................................................... 07 1. An Overview ............................................................................................................ 25 2. Role and Functions of the Ministry ................................................................................. 29 3. New Initiatives of the Ministry .......................................................................................... 33 4. Activities Under Information Sector ................................................................................. 39 5. Activities Under Broadcasting Sector .............................................................................. 89 6. Activities Under Films Sector ........................................................................................ 191 7. International Co-operation ........................................................................................... 239 8. Reservation for Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes ....................................................................................... 243 9. Representation of Physically Disabled Persons in Service .............................................. 245 10. Use of Hindi as Official Language ................................................................................... 249 11. Women Welfare Activities -

MSM and HIV/AIDS Risk in Asia Acknowledgments Executive Summary

SPECIAL REPORT August 2006 Risk inAsia: MSM andHIV/AIDS How CanItBeStopped? Epidemic AmongMSMand What IsFuelingthe Table of Contents Acknowledgments....................................................................................................................................i Executive Summary.................................................................................................................................1 Background................................................................................................................................................4 The.Asian.HIV/AIDS.Epidemic.Has.Targeted.Vulnerable.Communities...............................................4 HIV/AIDS.and.MSM.in.Asia:.A.Smoldering.Fire....................................................................................4 What Is the Target Population?.............................................................................................................5 Diverse.Populations;.Diverse.Terms.......................................................................................................5 MSM.as.a.Problematic.Categorization..................................................................................................5 MSM.in.Asia.Engage.in.a.Wide.Variety.of.Behaviors...........................................................................6 MSM.Exist.in.Both.Dense.and.Loose.Networks...................................................................................8 Lack of a Unified MSM Community.......................................................................................................8 -

1 Meeting on Issues Around Section 377, IPC Including Writ Petition Filed in Delhi High Court by Naz Foundation

Meeting on issues around Section 377, IPC including writ petition filed in Delhi High Court by Naz Foundation (India) Trust Venue: West End Hotel, Mumbai Date: 9 January 2005 Participants: KP (SAPPHO, Kolkata); RA (Samskar Alliance Project, Nizamabad, AP); PM (Darpan Foundation, Hyderabad); K (Friends, Hyderabad); CC (THAA, Chennai); AN (Snegyitham, Trichy, TN); KZ, CG, EF (Other Forum, Kolkata); SF (Coimbatore District Aravani Welfare Trust, TN); NS (Sahodaran, Pondicherry); PP (Suraksha, Hyderabad); Ch. Q (Prayatha, Nizamabad, AP); FA, MN, BB, Z, JK (SIAAP, Chennai); BQ, P (Sahodaran, Chennai); JRW (WINS, Tirupati, AP); FR (NIMSW/PLUS, Kolkata); PS (Mithrudu, Hyderabad); KB, NL (Humsaaya Welfare Sanstha, Mumbai); HD (SAATHII, Kolkata); ND (Manas Bengal, Kolkata); PVZ (NIPASHA+, Guntur); NF (SWAM, Chennai); EM (Spandhana, Mysore); RD (Gelaaya, Mysore); ON (LABIA, Mumbai); BD (Lakshya, Baroda); F, Dr. G (Udaan Trust, Mumbai); TH (PLUS, Kolkata); TC (Bandhan, Kolkata); BA (DMSC, Kolkata); MT (Naz Foundation International, Delhi) XTZ, OM, DU (Humsafar Trust, Mumbai); PX, SA (Naz Foundation India, Delhi); LA (New Delhi); M (Sangama, Bangalore); NSG, QP (FIRM, Kerala); VY (Mumbai); TO, XB (Gaybombay, Mumbai); NT (Aanchal Trust, Mumbai); MM (Voices against 377, Delhi); NA (Samapathik Trust, Pune); EC, MK and VB (Lawyers Collective HIV/AIDS Unit, Mumbai). EC started the meeting by welcoming all the participants and explained the material that had been handed out to them, which included minutes of the previous such meetings, a copy of the Delhi High Court (DHC) Order of September 2004 dismissing the petition challenging S.377, IPC and an agenda for the present meeting. Thereafter there was a round of introductions.