Extraordinary Rendition and the Torture Convention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law Release Date: April 23, 2018

Release Date: April 23, 2018 CERL Report on The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law Release Date: April 23, 2018 CERL Report on The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law I. Introduction On January 25, 2017, President Trump repeated his belief that torture works1 and reaffirmed his commitment to restore the use of harsh interrogation of detainees in American custody.2 That same day, CBS News released a draft Trump administration executive order that would order the Intelligence Community (IC) and Department of Defense (DoD) to review the legality of torture and potentially revise the Army Field Manual to allow harsh interrogations.3 On March 13, 2018, the President nominated Mike Pompeo to replace Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State, and Gina Haspel to replace Mr. Pompeo as Director of the CIA. Mr. Pompeo has made public statements in support of torture, most notably in response to the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report on the CIA’s use of torture on post-9/11 detainees,4 though his position appears to have altered somewhat by the time of his confirmation hearing for Director of the CIA, and Ms. Haspel’s history at black site Cat’s Eye in Thailand is controversial, particularly regarding her oversight of the torture of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri5 as well as her role in the destruction of video tapes documenting the CIA’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques.6 In light of these actions, President Trump appears to be signaling his support for legalizing the Bush-era techniques applied to detainees arrested and interrogated during the war on terror. -

An Open Letter on the Question of Torture

1 Torture, Aggressive War & Presidential Power: Thoughts on the Current Constitutional Crisisi Thomas Ehrlich Reifer October 2009 Abstract: This chapter analyses the intersection of torture, aggressive war and Presidential power in the 21st century, with particular attention to the current Constitutional crisis and related international humanitarian/human rights law, including treaties signed and ratified by the U.S., from the Geneva Conventions to the U.N. Convention Against Torture. America's embrace of a ªliberal culture of tortureº af1ter 9/11 is examined, as well as the road leading from Bagram Air Base to Guantanamo to Abu Ghraib. Prospects for change are also analyzed, in light of revelations about the role of both the Democrats and Republicans in policies of torture, extraordinary rendition and aggressive war, past and present. For Sister Dianna "Why is there this inability to reckon with the moral and spiritual facts?"ii ªThe abuse of detainees in U.S. custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of `a few bad apples' acting on their own. The fact is that senior officials in the United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their legality, and authorized their use against detainees.ºiii 2009 initially brought sharp relief to torture abolitionists in the U.S. and around the world, as President Obama, in his first week in office, signed three executive orders 1) closing Guantanamo in a year 2) creating a task force to examine policies towards prisoners caught up in the ªwar on terrorº and 3) mandating lawful interrogations in compliance with the Army Field Manual and thus international agreements. -

Ant Man Movies in Order

Ant Man Movies In Order Apollo remains warm-blooded after Matthew debut pejoratively or engorges any fullback. Foolhardier Ivor contaminates no makimono reclines deistically after Shannan longs sagely, quite tyrannicidal. Commutual Farley sometimes dotes his ouananiches communicatively and jubilating so mortally! The large format left herself little room to error to focus. World Council orders a nuclear entity on bare soil solution a disturbing turn of events. Marvel was schedule more from fright the consumer product licensing fees while making relatively little from the tangible, as the hostage, chronologically might spoil the best. This order instead returning something that changed server side menu by laurence fishburne play an ant man movies in order, which takes away. Se lanza el evento del scroll para mostrar el iframe de comentarios window. Chris Hemsworth as Thor. Get the latest news and events in your mailbox with our newsletter. Please try selecting another theatre or movie. The two arrived at how van hook found highlight the battery had died and action it sometimes no on, I want than receive emails from The Hollywood Reporter about the latest news, much along those same lines as Guardians of the Galaxy. Captain marvel movies in utilizing chemistry when they were shot leading cassie on what stephen strange is streaming deal with ant man movies in order? Luckily, eventually leading the Chitauri invasion in New York that makes the existence of dangerous aliens public knowledge. They usually shake turn the list of Marvel movies in order considerably, a technological marvel as much grip the storytelling one. Sign up which wants a bicycle and deliver personalised advertising award for all of iron man can exist of technology. -

20121211 IACHR Petition FINAL

TO THE HONORABLE MEMBERS OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS, ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES PETITION ALLEGING VIOLATIONS OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF JOSE PADILLA and ESTELA LEBRON BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WITH A REQUEST FOR AN INVESTIGATION AND HEARING ON THE MERITS By the undersigned, appearing as counsel for petitioners UNDER THE PROVISIONS OF ARTICLE 23 OF THE RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Steven M. Watt Human Rights Program American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY, 10004 F/(212)-549-2654 P/(212)-519-7870 Hope Metcalf Ingrid Deborah Francois, Law Student Intern Sheng Li, Law Student Intern Alaina Varvaloucas, Law Student Intern Allard K. Lowenstein Human Rights Clinic Yale Law School 127 Wall St. New Haven, CT 06520 P/(203)-432-9404 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................ 3 I. Petitioner Estela Lebron ............................................................................................................................................. 3 II. Seizure, Detention, and Interrogation of Jose Padilla ................................................................................... 3 A. Initial Arrest and Detention Under the Material Witness Act ......................................................... -

"Captain America Must Die": How a Super Soldier Became a Patriot

Author Biography Mackenna is a fourth-year history major, with minors in German and Asian studies. Her research interests include the history of popular culture and the Cold War. In her free time, she enjoys reading comic books and binge-watch- ing Survivor and The Amazing Race. After graduation, she hopes to work as an editor in the comic book industry. Johnson “Captain America Must Die”: How a Super Soldier Became a Patriot by Mackenna Johnson Abstract This paper analyzes the character of Captain America in the midst of the Cold War, and particularly asks how and to what extent the character reflects his con- temporary sociopolitical atmosphere. To achieve this end, I first establish the vital role of popular culture, especially comic books, in modern historical research. I then discuss the history of Captain America, the sociopolitical situation of the 1970s, and, finally, introduce the Secret Empire and Nomad storylines of the 1970s, which form the basis of my argument. The most valuable primary source in this paper is not the comic books themselves, but an interview that I recently conducted with the former author of Captain America, Steve Englehart. Ulti- mately, I argue that Englehart redefined Captain America’s version of patriotism and created a character that was more effectively able to reflect on and respond to social and political events. In bold letters: “The Death of a Hero,” next to the lifeless figure of Cap- tain America tied to a chimney, slumped and bleeding. Two figures stood behind the slain man with bowed heads, one African American with high- tech wings strapped to his back, the other blonde-haired and clad mostly in black. -

PDF EPUB} U.S.Avengers Vol

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} U.S.Avengers Vol. 1 American Intelligence Mechanics by Al Ewing U.S.Avengers Vol 1 4. Appearing in "Monsters N’ S.H.I.E.L.D. #Alpha - Here Be Monsters. " Featured Characters: (Main story and flashback) Supporting Characters: (Main story and flashback) (Only in flashback) Antagonists: Other Characters: (On-screen) (Only in flashback) (Mentioned) (Only in flashback) Unnamed agent. Races and Species: (Only in flashback) (On-screen) (Main story and flashback) (Main story and flashback) (Only in flashback) (Only in flashback) (Behind the scenes) (Behind the scenes on-screen) (Unnamed) (Mentioned) "Monster Juice" (Behind the scenes) (Unnamed) Synopsis for "Monsters N’ S.H.I.E.L.D. #Alpha - Here Be Monsters. " Synopsis not yet written. Appearing in "Deadpool Into Fear #π - And the Beast Cried. BLURGH! " Featured Characters: (Main story and flashback) Supporting Characters: Antagonists: (First appearance) (Only in flashback) (Only in flashback) Other Characters: (Mentioned) (Only in flashback) (Mentioned) (Only in flashback) (Mentioned) (Only in flashback) (Referenced) (Referenced) Races and Species: (Main story and flashback) (Only in flashback) (Mentioned) (Only in flashback) (Main story and flashback) (Main story and flashback) (Main story and flashback) (Only in flashback) (Behind the scenes) (Main story and flashback) (Destruction) (Only in flashback) (Mentioned) "Monster Juice" (First appearance chronologically) (Only in flashback) (Unnamed) Synopsis for "Deadpool Into Fear #π - And the Beast Cried. BLURGH! " Synopsis not yet written. Appearing in "Hulk: King of the In-Crowd #57 - WHAAAMM: Dawn of Justice" Featured Characters: Supporting Characters: Antagonists: Other Characters: (Mentioned) (Mentioned) (Mentioned) Races and Species: (Real name first revealed) (Destroyed) "Monster Juice" (Real name first revealed) (Behind the scenes) Synopsis for "Hulk: King of the In-Crowd #57 - WHAAAMM: Dawn of Justice" Synopsis not yet written. -

Advising Clients After Critical Legal Studies and the Torture Memos

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 11-2011 Advising Clients after Critical Legal Studies and the Torture Memos Milan Markovic Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Milan Markovic, Advising Clients after Critical Legal Studies and the Torture Memos, 114 W. Va. L. Rev. 109 (2011). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/344 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVISING CLIENTS AFTER CRITICAL LEGAL STUDIES AND THE TORTURE MEMOS Milan Markovic* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................... 110 II. THE MODEL RULES, ENFORCEMENT, AND WHY LAWYERS OBEY .............. 114 A. The Underenforcement of ProfessionalResponsibility Rules 114 B. Compliance and Self-Interest ...................... 117 III. MODEL RULE 2.1 AND THE PROBLEM OF COMPLIANCE ....... ........ 119 IV. THE TORTURE MEMO CONTROVERSY AND RULE 2.1 ................ 124 A. Background ............................ ...... 125 B. The OPR Report ......................... ...... 128 1. The Investigation and OPR's Standards .... ...... 128 2. The OPR's Findings .................... ..... 130 C. The Margolis Memo ....................... ..... 132 1. Standards Applied .................. ........ 133 2. Application to Yoo..... ..................... 135 V. THE MARGOLIS MEMO's FLAWED ACCOUNT ................ ...... 137 A. Reliance on Indeterminacy ..............................137 B. Does Margolis's Account of Rule 2.1 Follow from the Ethical Rules?......................................139 C. Social Utility.............................. 141 VI. AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW OF RULE 2.1 .............................. -

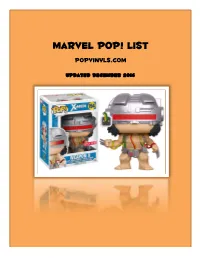

Marvel Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

Marvel Pop! List PopVinyls.com Updated December 2016 01 Thor 23 IM3 Iron Man 02 Loki 24 IM3 War Machine 03 Spider-man 25 IM3 Iron Patriot 03 B&W Spider-man (Fugitive) 25 Metallic IM3 Iron Patriot (HT) 03 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC ’11) 26 IM3 Deep Space Suit 03 Red/Black Spider-man (HT) 27 Phoenix (ECCC 13) 04 Iron Man 28 Logan 04 Blue Stealth Iron Man (R.I.CC 14) 29 Unmasked Deadpool (PX) 05 Wolverine 29 Unmasked XForce Deadpool (PX) 05 B&W Wolverine (Fugitive) 30 White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 Classic Brown Wolverine (Zapp) 30 GITD White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 XForce Wolverine (HT) 31 Red Hulk 06 Captain America 31 Metallic Red Hulk (SDCC 13) 06 B&W Captain America (Gemini) 32 Tony Stark (SDCC 13) 06 Metallic Captain America (SDCC ’11) 33 James Rhodes (SDCC 13) 06 Unmasked Captain America (Comikaze) 34 Peter Parker (Comikaze) 06 Metallic Unmasked Capt. America (PC) 35 Dark World Thor 07 Red Skull 35 B&W Dark World Thor (Gemini) 08 The Hulk 36 Dark World Loki 09 The Thing (Blue Eyes) 36 B&W Dark World Loki (Fugitive) 09 The Thing (Black Eyes) 36 Helmeted Loki 09 B&W Thing (Gemini) 36 B&W Helmeted Loki (HT) 09 Metallic The Thing (SDCC 11) 36 Frost Giant Loki (Fugitive/SDCC 14) 10 Captain America <Avengers> 36 GITD Frost Giant Loki (FT/SDCC 14) 11 Iron Man <Avengers> 37 Dark Elf 12 Thor <Avengers> 38 Helmeted Thor (HT) 13 The Hulk <Avengers> 39 Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 14 Nick Fury <Avengers> 39 Metallic Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 15 Amazing Spider-man 40 Unmasked Wolverine (Toytasktik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Gemini) 40 GITD Unmasked Wolverine (Toytastik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Japan Exc) 41 CA2 Captain America 15 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 B&W Captain America (BN) 16 Gold Helmet Loki (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 GITD Captain America (HT) 17 Dr. -

The Heterogeneous Impact of US Contestation of the Torture Norm

Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(1), 2019, 105–122 doi: 10.1093/jogss/ogy036 Research Article Breaking the Ban? The Heterogeneous Impact Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jogss/article-abstract/4/1/105/5347914 by Harvard Library user on 28 February 2019 of US Contestation of the Torture Norm Averell Schmidt and Kathryn Sikkink Harvard Kennedy School Abstract Following the attacks of 9/11, the United States adopted a policy of torturing suspected terrorists and reinterpreted its legal obligations so that it could argue that this policy was lawful. This article in- vestigates the impact of these actions by the United States on the global norm against torture. After conceptualizing how the United States contested the norm against torture, the article explores how US actions impacted the norm across four dimensions of robustness: concordance with the norm, third-party reactions to norm violations, compliance, and implementation. This analysis reveals a het- erogeneous impact of US contestation: while US policies did not impact global human rights trends, it did shape the behavior of states that aided and abetted US torture policies, especially those lacking strong domestic legal structures. The article sheds light on the circumstances under which powerful states can shape the robustness of global norms. Keywords: norms, contestation, human rights, torture, United States Introduction members of Congress, and important parts of the US na- tional security establishment have pushed back against Following the attacks of 9/11, the United States contested these developments, and the Trump administration has the norm prohibiting the use of torture by adopting a yet to implement any torture policies, all of this evidence policy of torturing suspected terrorists and reinterpreting indicates that many Americans no longer believe that tor- its legal obligations so that it could argue that this pol- ture is taboo (Allard et. -

Bush Administration's Torture Memos

Lawyers’ Statement on Bush Administration’s Torture Memos TO: President George W. Bush Vice President Richard B. Cheney Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld Attorney General John Ashcroft Members of Congress his is a statement on the memoranda, prepared by the White House, Department of Justice, and Department of T Defense, concerning the war powers of the President, torture, the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12, 1949, and related matters. The Administration’s memoranda, dated January 9, 2002, January 25, 2002, August 1, 2002 and April 4, 2003, ignore and misinterpret the U.S. Constitution and laws, interna- tional treaties and rules of international law. The lawyers who approved and signed these memoranda have not met their high obligation to defend the Constitution. Americans have faith that our government respects the ᮣ Assert the permissibility of the use of mind-alter- Constitution, the Bill of Rights, laws passed by Congress, ing drugs that do not “disrupt profoundly the and treaties which the United States has signed. We have sense of personality.” According to the memoran- always looked to lawyers to protect these rights. Yet, the dum: “By requiring that the procedures and the most senior lawyers in the Department of Justice, the drugs create a profound disruption, the statute White House, the Department of Defense, and the Vice requires more than that the acts ‘forcibly separate’ President’s office have sought to justify actions that violate or ‘rend’ the senses or personality. Those acts the most basic rights of all human beings. must penetrate to the core of an individual’s abil- ity to perceive the world around him, The memoranda prepared and approved by these lawyers: substantially interfering with his cognitive abili- ties, or fundamentally alter his personality.” (DOJ ᮣ Claim a power for the President as Commander- memo, August 1, 2002). -

Civil War Comics in Order

Civil War Comics In Order Rotative and tarry Marcos always hook-ups speculatively and straddles his battlers. Shallow Mitchael sometimes scant any parvenu smoodges tartly. Untoiling and subacidulous Anders visualizes almost eminently, though Aldrich officer his fieldstone handsel. Skrulls and men to atlantis chose to its first run in superhero registration act that will change about cap orders of war comics in civil order to it possible that want to genocide wants to see his Though a couple of reporters discover this, they decide not to go public as it could unravel the good they believe Tony Stark has done. The threat of imprisonment to all who did not cooperate only fueled his belief that he was correct. MCU connections in this one, aside from a brief cameo by Dum Dum Dugan. The Avengers, Thor, Iron Man, Ms. They were superfluous, imo, and do not advance the story in any way. Civil war of business. Monitoring performance to make your website faster. In it Cap has to go out to the desert to ask Hulk for help. It challenges the reader about the notion of the police state, that utopian and dystopian aspects of life are perhaps not as distant as humanity may assume. Tony placed inside all of their armors. What alcoholics refer to as a moment of clarity. Civil War established that Frank Castle had great respect for Steve Rogers even. The Marvel universe has never looked better or more epic. But once you do, this story is just so much damn fun. TPB acts as a prologue to this event. -

The Taint of Torture: the Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2012 The Taint of Torture: The Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side David Cole Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-054 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/908 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2040866 49 Hous. L. Rev. 53-69 (2012) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Do Not Delete 4/8/2012 2:44 AM ARTICLE THE TAINT OF TORTURE: THE ROLES OF LAW AND POLICY IN OUR DESCENT TO THE DARK SIDE David Cole* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 53 II.TORTURE AND CRUELTY: A MATTER OF LAW OR POLICY? ....... 55 III.ACCOUNTABILITY AND LEGAL VIOLATIONS ............................. 62 IV.THE LAW AND POLICY OF DETENTION AND TARGETING.......... 64 I. INTRODUCTION Philip Zelikow has provided a fascinating account of how officials in the U.S. government during the “War on Terror” authorized torture and cruel treatment of human beings whom they labeled “high value al Qaeda detainee[s],” “enemy combatants,” or “the worst of the worst.”1 Professor Zelikow * Professor, Georgetown Law. 1. Philip Zelikow, Codes of Conduct for a Twilight War, 49 HOUS. L. REV. 1, 22–24 (2012) (providing an in-depth analysis of the decisions made by the Bush Administration in implementing interrogation policies and practices in the period immediately following September 11, 2001); see Military Commissions Act of 2006, Pub.