Film, Literature, and Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Adaptation

Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Bókmenntir, Menning og Miðlun The Art of Adaptation The move from page to stage/screen, as seen through three films Margrét Ann Thors 301287-3139 Leiðbeinandi: Guðrún Björk Guðsteinsdóttir Janúar 2020 2 Big TAKK to ÓBS, “Óskar Helps,” for being IMDB and the (very) best 3 Abstract This paper looks at the art of adaptation, specifically the move from page to screen/stage, through the lens of three films from the early aughts: Spike Jonze’s Adaptation, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman, or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance, and Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? The analysis identifies three main adaptation-related themes woven throughout each of these films, namely, duality/the double, artistic madness/genius, and meta- commentary on the art of adaptation. Ultimately, the paper seeks to argue that contrary to common opinion, adaptations need not be viewed as derivatives of or secondary to their source text; rather, just as in nature species shift, change, and evolve over time to better suit their environment, so too do (and should) narratives change to suit new media, cultural mores, and modes of storytelling. The analysis begins with a theoretical framing that draws on T.S. Eliot’s, Linda Hutcheon’s, Kamilla Elliott’s, and Julie Sanders’s thoughts about the art of adaptation. The framing then extends to notions of duality/the double and artistic madness/genius, both of which feature prominently in the films discussed herein. Finally, the framing concludes with a discussion of postmodernism, and the basis on which these films can be situated within the postmodern artistic landscape. -

Film Adaptation As an Act of Communication: Adopting a Translation-Oriented Approach to the Analysis of Adaptation Shifts Katerina Perdikaki

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:10 p.m. Meta Journal des traducteurs Translators’ Journal Film Adaptation as an Act of Communication: Adopting a Translation-oriented Approach to the Analysis of Adaptation Shifts Katerina Perdikaki Volume 62, Number 1, April 2017 Article abstract Contemporary theoretical trends in Adaptation Studies and Translation Studies URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1040464ar (Aragay 2005; Catrysse 2014; Milton 2009; Venuti 2007) envisage synergies DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1040464ar between the two areas that can contribute to the sociocultural and artistic value of adaptations. This suggests the application of theoretical insights See table of contents derived from Translation Studies to the adaptation of novels for the screen (i.e., film adaptations). It is argued that the process of transposing a novel into a filmic product entails an act of bidirectional communication between the book, Publisher(s) the novel and the involved contexts of production and reception. Particular emphasis is placed on the role that context plays in this communication. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Context here is taken to include paratextual material pertinent to the adapted text and to the film. Such paratext may lead to fruitful analyses of adaptations ISSN and, thus, surpass the myopic criterion of fidelity which has traditionally dominated Adaptation Studies. The analysis uses examples of adaptation shifts 0026-0452 (print) (i.e., changes between the source novel and the film adaptation) from the film 1492-1421 (digital) P.S. I Love You (LaGravenese 2007), which are examined against interviews of the author, the director and the cast, the film trailer and one film review. -

Literature on Screen, a History: in the Gap Timothy Corrigan University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (CIMS) Cinema and Media Studies Program 9-2007 Literature on Screen, A History: In the Gap Timothy Corrigan University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/cims_papers Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Film Production Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Corrigan, T. (2007). Literature on Screen, A History: In the Gap. In D. Cartmell & I. Whelehan (Eds.), The aC mbridge Companion to Literature on Screen (pp. 29-44). New York: Cambridge University Press. [10.1017/CCOL0521849624.003] This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/cims_papers/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Literature on Screen, A History: In the Gap Abstract Perhaps more than any other film practices, cinematic adaptations have drawn the attention, scorn, and admiration of movie viewers, historians, and scholars since 1895. Indeed, even before this origin of the movies - with the first public projections of films by Auguste and Louis Lumière in France and Max and Emil Skladanowsky in Germany - critical voices worried about how photography had already encroached on traditional aesthetic terrains and disciplines, recuperating and presumably demeaning pictorial or dramatic subjects by adapting them as mechanical reproductions. After 1895, however, film culture moved quickly to turn this cultural anxiety to its advantage, as filmmakers worked to attract audiences with well-known images from books now brought to life as Cinderella (1900), Gulliver's Travels (1902), and The aD mnation of Faust (1904). -

CALENDAR January 23

BOWDOIN COLLEGE / ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND Cinema Studies CINE 2116 / SPAN 3116: Spanish Cinema: Taboo and Tradition Spring 2019 / MW 10:05 Elena Cueto Asín. Sills Hall 210 – 725‐3312 – email: [email protected] Office hours: Monday 2:45‐4, or by appointment. This course introduces students to film produced in Spain, from the silent era to the present, focusing on the ways in which cinema can be a vehicle for promoting social and cultural values, as well as for exposing social, religious, sexual, or historical taboos in the form of counterculture, protest, or as a means for society to process change or cope with issues from the past. Looks at the role of film genre, authorship, and narrative in creating languages for perpetuating or contesting tradition, and how these apply to the specific Spanish context. GRADE Class Participation 40% Essays 60% MATERIALS Film available on reserve at the LMC or/and on‐line. Readings on‐line and posted on blackboard CALENDAR January 23. Introduction January 28 ¡Átame! - Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Pedro Almodóvar 1989) Harmony Wu “The Perverse Pleasures of Almodovar’s Átame” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 5 (3) 2004: 261-271. Reviews and controversy: New York Times: February 11, April 22 and 23, June 24, May 4, May 24, July 20 of 1989 January 30 Silent Cinema: The Unconventional and the Conventional El perro andaluz- Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel 1927) Jordan Cox “Suffering as a Form of Pleasure: An Exploration of Black Humor in Un Chien Andalou” Film Matters 5(3) 2014: 14-18 February 4 and 6 La aldea maldita- The Cursed Village (Florian Rey 1929) Tatjana Pavlović 100 years of Spanish cinema [electronic resource] Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 15-20 Sánchez Vidal, Agustin. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Avance Largometrajes 2014Feature Films Preview

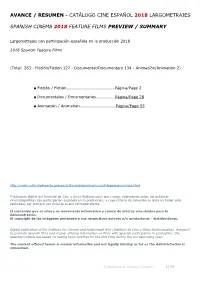

AVANCE / RESUMEN - CATÁLOGO CINE ESPAÑOL 2018 LARGOMETRAJES SPANISH CINEMA 2018 FEATURE FILMS PREVIEW / SUMMARY Largometrajes con participación española en la producción 2018 2018 Spanish Feature Films (Total: 263 - Ficción/Fiction 127 - Documental/Documentary 134 - Animación/Animation 2) ■ Ficción / Fiction…………………………………………Página/Page 2 ■ Documentales / Documentaries……………...Página/Page 28 ■ Animación / Animation……………………………..Página/Page 55 http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/cine/mc/catalogodecine/inicio.html Publicación digital del Instituto de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales que recoge información sobre las películas cinematográficas con participación española en la producción, y cuyo criterio de selección se basa en haber sido calificadas por primera vez durante el año correspondiente. El contenido que se ofrece es meramente informativo y carece de efectos vinculantes para la Administración. El copyright de las imágenes pertenece a sus respectivos autores y/o productoras - distribuidoras. Digital publication of the Institute for Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (Instituto de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales), designed to promote Spanish films and mainly offering information on films with Spanish participation in production; the selection criteria are based on having been certified for the first time during the corresponding year. The content offered herein is merely informative and not legally binding as far as the Administration is concerned. © Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte 1 | 55 LARGOMETRAJES 2018 SPANISH FEATURE FILMS - FICCIÓN / FICTION #SEGUIDORES - #FOLLOWERS Dirección/Director: Iván Fernández de Córdoba Productoras/Prod. Companies: NAUTILUS FILMS & PROJECTS, S.L. Intérpretes/Cast: Sara Sálamo, Jaime Olías, Rodrigo Poisón, María Almudéver, Norma Ruiz y Aroa Ortigosa Drama 76’ No recomendada para menores de 12 años / Not recommended for audiences under 12 https://www.facebook.com/seguidoreslapelicula/ ; https://www.instagram.com/seguidoreslapelicula/ Tráiler: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RK5vUNlMJNc ¿QUÉ TE JUEGAS? - GET HER.. -

Rafael Azcona: Atrapados Por La Vida

Juan Carlos Frugone Rafael Azcona: atrapados por la vida 2003 - Reservados todos los derechos Permitido el uso sin fines comerciales Juan Carlos Frugone Rafael Azcona: atrapados por la vida Quiero expresar mi agradecimiento profundo a Cristina Olivares, Ignacio Darnaude Díaz, Fernando Lara y Manuela García de la Vega, quienes -de una u otra manera- me han ayudado para que este libro sea una realidad. También, por sus consejos, un agradecimiento para Luis Sanz y José Luis García Sánchez. Y ¿por qué no?, a Rafael Azcona, quien no concede nunca una entrevista, pero me concedió la riqueza irreproducible de muchas horas de su charla. Juan Carlos Frugone [5] Es absurdo preguntarle a un autor una explicación de su obra, ya que esta explicación bien puede ser lo que su obra buscaba. La invención de la fábula precede a la comprensión de su moraleja. JORGE LUIS BORGES [7] ¿Por qué Rafael Azcona? Rafael Azcona no sabe nada de cine. Porque ¿quién que sepa de cine puede negar su aporte indudable a muchas de las obras maestras del cine español e italiano de los últimos treinta años? Él lo niega. Todos sabemos que el cine es obra de un director, de la persona cuyo nombre figura a continuación de ese cartel que señala «un film de». Pero no deja de ser curioso que el común denominador de películas como El cochecito, El pisito, Plácido, El verdugo, Ana y los lobos, El jardín de las delicias, La prima Angélica, Break-up, La gran comilona, Tamaño natural, La escopeta nacional, El anacoreta, La corte de faraón y muchísimas más de la misma envergadura, sea el nombre y el apellido de Rafael Azcona. -

80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20Am, Salomon 004

Brown University Department of Hispanic Studies HISP 1290J. Spain on Screen: 80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20am, Salomon 004 Prof. Sarah Thomas 84 Prospect Street, #301 [email protected] Tel.: (401) 863-2915 Office hours: Thursdays, 11am-1pm Course description: Spain’s is one of the most dynamic and at the same time overlooked of European cinemas. In recent years, Spain has become more internationally visible on screen, especially thanks to filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro, Pedro Almodóvar, and Juan Antonio Bayona. But where does Spanish cinema come from? What themes arise time and again over the course of decades? And what – if anything – can Spain’s cinema tell us about the nation? Does cinema reflect a culture or serve to shape it? This course traces major historical and thematic developments in Spanish cinema from silent films of the 1930s to globalized commercial cinema of the 21st century. Focusing on issues such as landscape, history, memory, violence, sexuality, gender, and the politics of representation, this course will give students a solid training in film analysis and also provide a wide-ranging introduction to Spanish culture. By the end of the semester, students will have gained the skills to write and speak critically about film (in Spanish!), as well as a deeper understanding and appreciation of Spain’s culture, history, and cinema. Prerequisite: HISP 0730, 0740, or equivalent. Films, all written work and many readings are in Spanish. This is a writing-designated course (WRIT) so students should be prepared to craft essays through multiple drafts in workshops with their peers and consultation with the professor. -

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title 10

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title Film Date Rating(%) 2046 1-Feb-2006 68 120BPM (Beats Per Minute) 24-Oct-2018 75 3 Coeurs 14-Jun-2017 64 35 Shots of Rum 13-Jan-2010 65 45 Years 20-Apr-2016 83 5 x 2 3-May-2006 65 A Bout de Souffle 23-May-2001 60 A Clockwork Orange 8-Nov-2000 81 A Fantastic Woman 3-Oct-2018 84 A Farewell to Arms 19-Nov-2014 70 A Highjacking 22-Jan-2014 92 A Late Quartet 15-Jan-2014 86 A Man Called Ove 8-Nov-2017 90 A Matter of Life and Death 7-Mar-2001 80 A One and A Two 23-Oct-2001 79 A Prairie Home Companion 19-Dec-2007 79 A Private War 15-May-2019 94 A Room and a Half 30-Mar-2011 75 A Royal Affair 3-Oct-2012 92 A Separation 21-Mar-2012 85 A Simple Life 8-May-2013 86 A Single Man 6-Oct-2010 79 A United Kingdom 22-Nov-2017 90 A Very Long Engagement 8-Jun-2005 80 A War 15-Feb-2017 91 A White Ribbon 21-Apr-2010 75 Abouna 3-Dec-2003 75 About Elly 26-Mar-2014 78 Accident 22-May-2002 72 After Love 14-Feb-2018 76 After the Storm 25-Oct-2017 77 After the Wedding 31-Oct-2007 86 Alice et Martin 10-May-2000 All About My Mother 11-Oct-2000 84 All the Wild Horses 22-May-2019 88 Almanya: Welcome To Germany 19-Oct-2016 88 Amal 14-Apr-2010 91 American Beauty 18-Oct-2000 83 American Honey 17-May-2017 67 American Splendor 9-Mar-2005 78 Amores Perros 7-Nov-2001 85 Amour 1-May-2013 85 Amy 8-Feb-2017 90 An Autumn Afternoon 2-Mar-2016 66 An Education 5-May-2010 86 Anna Karenina 17-Apr-2013 82 Another Year 2-Mar-2011 86 Apocalypse Now Redux 30-Jan-2002 77 Apollo 11 20-Nov-2019 95 Apostasy 6-Mar-2019 82 Aquarius 31-Jan-2018 73 -

Novel to Novel to Film: from Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway to Michael

Rogers 1 Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ Novel to Novel to Film: From Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway to Michael Cunningham’s and Daldry-Hare’s The Hours Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Literature at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Fall 2015 By Jacob Rogers ____________________ Thesis Director Dr. Kirk Boyle ____________________ Thesis Advisor Dr. Lorena Russell Rogers 2 All the famous novels of the world, with their well known characters, and their famous scenes, only asked, it seemed, to be put on the films. What could be easier and simpler? The cinema fell upon its prey with immense rapacity, and to this moment largely subsists upon the body of its unfortunate victim. But the results are disastrous to both. The alliance is unnatural. Eye and brain are torn asunder ruthlessly as they try vainly to work in couples. (Woolf, “The Movies and Reality”) Although adaptation’s detractors argue that “all the directorial Scheherezades of the world cannot add up to one Dostoevsky, it does seem to be more or less acceptable to adapt Romeo and Juliet into a respected high art form, like an opera or a ballet, but not to make it into a movie. If an adaptation is perceived as ‘lowering’ a story (according to some imagined hierarchy of medium or genre), response is likely to be negative...An adaptation is a derivation that is not derivative—a work that is second without being secondary. -

Film Adaptation As the Interface Between Creative Translation and Cultural Transformation

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 29 – January 2018 Film adaptation as the interface between creative translation and cultural transformation: The case of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby Katerina Perdikaki, University of Surrey ABSTRACT Adaptation is prominent in many facets of the creative industries, such as the performing arts (e.g. theatre, opera) and various forms of media (e.g. film, television, radio, video games). As such, adaptation can be regarded as the creative translation of a narrative from one medium or mode to another. This paper focuses on film adaptation and examines its role in cultural production and dissemination within the broader polysystem (Even-Zohar 1978a). Adaptation has been viewed as a process which can shed light on meaningful questions on a social, cultural and ideological level (cf. Casetti 2004; Corrigan 2014; Venuti 2007). Nevertheless, an integrated framework for the systematic analysis of adaptations seems to have remained under-researched. The paper puts forward a model for adaptation analysis which highlights the factors that condition adaptation as a process and as a product. In this way, adaptation is studied as a system monitored by economic, creative and social agendas which nevertheless transforms the communicating vessels of the literary system and the film industry. To illustrate this, the paper discusses how the two systems and various creative and socioeconomic considerations interlace in the latest film adaptation of The Great Gatsby (Luhrmann 2013). It concludes on the benefits of a holistic approach to adaptation. KEYWORDS Film adaptation, translation, polysystem, paratexts, creative industries, The Great Gatsby. 1. Introduction Adaptations play a crucial part in the contemporary creative industries. -

Where Has All the Magic Gone?: Audience Interpretive Strategies of the Hobbit’S Film- Novel Rivalry

. Volume 13, Issue 2 November 2016 Where has all the magic gone?: Audience interpretive strategies of The Hobbit’s film- novel rivalry Jonathan Ilan, Bar-Ilan University, Israel Amit Kama, Yezreel Valley Academic College, Israel Abstract: The complex relations between words and images are debated in various disciplines and have been in a variety of modes a thorny issue for centuries. Words are constantly used to represent or embody images (conceptualized as ekphrasis) and vice versa. At the same time, however, words are also considered not sufficient to represent the visual sign, which cannot rely entirely on text. Similarly, the visual cannot rely entirely on the verbal; its understanding should come from representational practices alone, as there is something in the image that is ‘purely image’. Films and novels are accordingly opposed, considered as two separate ‘pure’ entities that are not translatable, and yet share stylistic, narrative, and cultural connections. This essay tackles such relations as they are manifested in audience members’ discussions of the cinematographic Hobbit adaptation(s). More specifically, it is focused on their interpretive strategies in the ways these relate to the novel-film rivalry. Based on qualitative thematic analyses of the 251 Israeli respondents’ open-ended answers, we demonstrate how the film-novel rivalry unveils itself in the audience reception of the film(s) adaptations. Findings reveal diverse and even paradoxical tensions: From a standpoint that the movie is considered a perfect or even ‘better’ representation of the novel, to vehement criticism that it vandalizes the original and ‘misses’ its ‘purpose’ completely, designed entirely to make profit.