Paella Party!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instruction Manual Instruction Piezas De Repuesto Se Pueden Encontrar En Línea

1 www.AromaCo.com/Support . ARC-687D-1NG found online. Visit online. found replacement parts can be be can parts replacement questions and even even and questions Manual de instrucciones Answers to many common common many to Answers La arrocera favorita de los Estados Unidos Arrocera y vaporera 1-800-276-6286 . ¿Preguntas o dudas acerca Call us toll-free at toll-free us Call de su arrocera? experts are happy to help. to happy are experts Antes de regresar a la tienda... Aromas customer service service customer Aromas Nos expertos de servicio al cliente Before returning to the store... the to returning Before estará encantado de ayudarle. Llámenos al número gratuito a about your rice cooker? rice your about 1-800-276-6286. Questions or concerns concerns or Questions Americas Favorite Rice Cooker Rice Favorite Americas Rice Cooker & Food Steamer Food & Cooker Rice Las respuestas a muchas preguntas comunes e incluso Instruction Manual Instruction piezas de repuesto se pueden encontrar en línea. Visita: www.AromaCo.com/Support. ARC-687D-1NG 54 Todos los derechos reservados. derechos los Todos ©2012 Aroma Housewares Company Housewares Aroma ©2012 www.AromaCo.com 1-800-276-6286 U.S.A. San Diego, CA 92121 CA Diego, San 6469 Flanders Drive Flanders 6469 Aroma Housewares Co. Housewares Aroma Congratulations on your purchase of the Aroma® 14-Cup Digital Rice Cooker. In no time at all, youll be making fantastic, restaurant-quality rice at the touch of a button! Por: Publicada Whether long, medium or short grain, this cooker is specially calibrated to prepare all varieties of rice, including tough-to-cook whole grain brown rice, to uffy perfection. -

2021 United Way Cookbook Index

Index Ahi Carpaccio ........................................................................................... 1 Almond Graham Crackers .................................................................... 121 Aunty Elaine’s Magic Jello .................................................................... 122 Baby Arugula and Watermelon Summer Salad ...................................... 21 Baked Chicken ....................................................................................... 55 Baked Shoyu Chicken ............................................................................ 56 Baked Spaghetti ..................................................................................... 57 Baked Sushi ........................................................................................... 22 Baked Tofu.............................................................................................. 59 Baked Tofu (Ornish Friendly) .................................................................. 58 Balsamic Glaze..................................................................................... 148 Banana Bread....................................................................................... 123 Banana Muffins with Fancy Topping ..................................................... 124 BBQ Hamburger Patties ......................................................................... 60 Beef or Chicken Broccoli ........................................................................ 61 Beef Stew .............................................................................................. -

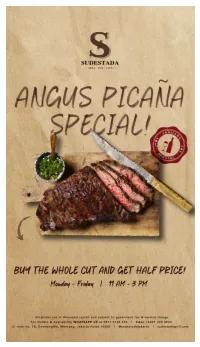

Sudestada-ALL-Menu-2.Pdf

est. 2019 ALL DAY MENU #SudestadaJakarta BIENVENIDO A SUDESTADA JAKARTA Welcome to SUDESTADA JAKARTA, a specialty Argentinian Grill, Bar and Cafe inspired by the vivacious Latin culture. SUDESTADA /su.des.ta.da/ (n.) “powerful wind, particularly the cool strong breeze before a mighty storm” is regarded as an auspicious name in Argentinian culture that brings good luck. Bringing vibrant Argentinian charm to Jakarta’s Aer a taste of our honest cuisine and being culinary scene, Sudestada's guests can expect a immersed in the enchanting neoclassical wholesome and authentic dining experience. ambiance, the wines and the culture, you may Under the helm of our well-seasoned executive come as a guest, but you will leave as el amigo. chef, Victor Taborda, an Argentine native with his team of experienced cooks, their passion and Buen provecho, hope create a new benchmark for Latin culinary oerings, taking them to new heights with contemporary touches that translates from the Enjoy�Your�Meal! plate to your palate. @sudestadajakarta 1 Chef Victor is an Argentinian native of Neuquen, a beautiful town on northern Patagonia. Spent his childhood helping out in his father’s steakhouse has allowed Victor to absorb the concepts of Argentinian Asado by blood. He shares his profound love for his country and its remarkable cuisine to a wider audience who are constantly hungry for food and authentic experiences, Jakarta and beyond. Chef Victor Taborda Argentinian Style Pizzas PIZZAS ARGENTINAS NAPOLITANA Tomatoes, oregano, green olives ..................... 140 PEPPERONI Beef pepperoni .................................................. 150 MORRONES Y JAMON Red bell peppers and ham ................... 170 MOZZARELLA Tomato sauce and olives ............................... -

Crisostomo-Main Menu.Pdf

APPETIZERS Protacio’s Pride 345 Baked New Zealand mussels with garlic and cheese Bagumbayan Lechon 295 Lechon kawali chips with liver sauce and spicy vinegar dip Kinilaw ni Custodio 295 Kinilaw na tuna with gata HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Tinapa ni Tiburcio 200 310 Smoked milkfish with salted egg Caracol Ginataang kuhol with kangkong wrapped in crispy lumpia wrapper Tarsilo Squid al Jillo 310 Sautéed baby squid in olive oil with chili and garlic HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Calamares ni Tales 325 Fried baby squid with garlic mayo dip and sweet chili sauce Mang Pablo 385 Crispy beef tapa Paulita 175 Mangga at singkamas with bagoong Macaraig 255 Bituka ng manok AVAILABLE IN CLASSIC OR SPICY Bolas de Fuego 255 Deep-fried fish and squid balls with garlic vinegar, sweet chili, and fish ball sauce HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Lourdes 275 Deep-fried baby crabs SEASONAL Sinuglaw Tarsilo 335 Kinilaw na tuna with grilled liempo Lucas 375 Chicharon bulaklak at balat ng baboy SIZZLING Joaquin 625 Tender beef bulalo with mushroom gravy Sisig Linares 250 Classic sizzling pork sisig WITH EGG 285 Victoria 450 Setas Salpicao 225 Sizzling salmon belly with sampalok sauce Sizzling button mushroom sautéed in garlic and olive oil KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Carriedo 385 Sautéed shrimp gambas cooked -

Shellfish and Chicken Paella

Shellfish and Chicken Paella Paella is arguably the national dish of Spain, and the best ones, it is said, come from Valencia in the south. Gloria and I had our best paella there in an unassuming little restaurant where the lady owner was the chef. I have made paella with all varieties of rice, although conventionally it is made with Spanish short-grain. Italian Arborio rice, French rice from Camargue, and Asian or American rice work as well. Although true paella is made in a shallow tin pan on an open fire and can include rabbit as well as snails or eel, I make mine with chorizo sausage and chicken thighs, adding shellfish at the last moment. I also cover the pan, which is not the traditional procedure, because this helps the mixture cook more evenly. The chicken, chorizo, mushrooms, onion, and garlic can be browned a couple of hours ahead. I like to use commercial alcaparrado, a mixture of olives, red pimientos, and capers that my wife uses in her Caribbean cooking, and hot salsa, both of which are available in markets. 4 Servings • 3 tablespoons good olive oil • 1 chorizo sausage (about 1/4 pound), skinned and cut into 12 slices • 4 small skinless chicken thighs (about 1 pound total) • 1 cup diced (1/2-inch) white mushrooms • 1 cup coarsely chopped onion • 1 tablespoon coarsely chopped garlic • 1 1/4 cups short-grain rice (Spanish, Italian, French, Asian, or American) • 1 cup alcaparrado, drained and rinsed under cold water, or a mixture of equal parts diced green olives, red pimiento, capers, and garlic • 1 cup canned diced tomatoes in sauce • About 11/2 teaspoons saffron pistils • 1/3 cup hot salsa • 1 1/4 cups chicken stock, homemade (page 37), or low-salt canned chicken broth • 1 1/4 teaspoons salt • 20 mussels (about 14 ounces total), washed and debearded • 5 large sea scallops (about 6 ounces total), rinsed under cold water to remove any sand • 12 uncooked large shrimp (about 1/2 pound total), with shells left on • 1/2 cup frozen petite peas Heat the oil in a large saucepan. -

Menu Marcelona ANG.Pdf

ENSALADAS Y SOPAS SOUPS AND SALADS Escudella barrellada 65 MAD Catalan chicken soup with pine nuts and noodles Gazpacho andaluz 60 MAD LAS PATATAS Y LOS HUEVOS Chilled mix vegetables soup, crouton POTATOES AND EGGS Ensaladilla rusa 60 MAD Patatas Bravas 50 MAD Russian salad Spicy potatoes, aïoli and tomato sauce Empedrat de cigrons amb bacalla 75 MAD Tortilla de patatas 55 MAD Salted cod fish and chickpeas salad Spanish omelette with potatoes and onions Escalibada amb anxoves i romesco 60 MAD Huevos estrellados con jamon 80 MAD Roasted bell pepper, anchovies, romesco sauce Fried egg with pork ham LAS PAELLAS Ous amb Sanfaina 70 MAD 1pers / 2PERS Poached egg, with ratatouille PAELLAS Paella de Arros negre amb 180 MAD / 280 MAD chipirons de platja LOS ENTRANTES DEL MAR Black rice with baby squid and garlic mayonnaise SEAFOOD APETIZERS Paella mixta 180 MAD / 280 MAD Paella with chicken and calamari Calamares a la romana 95 MAD Fried calamari Fideua de marisco 190 MAD / 300 MAD Vermicelli with seafood Pulpo a la gallega 80 MAD Octopus galician style LOS PLATOS FUERTES Boquerones en Vinagre 45 MAD MAIN COURSES Anchovies in vinegar Suquet de peix com a l’Emporda 190 MAD Catalan fisherman hot pot Mejillones en Vinagreta 80 MAD Mussels with bell pepper dressing Bacalla a la llauna dela tieta 180 MAD Cod fish, white beans and boiled egg Gambas al Ajillo 80 MAD Prawns, garlic and paprika Pollo al ajillo con pimientos 160 MAD Roasted chicken with garlic sauce Sardinas fritas con mahonesa 45 MAD Fried sardines with mayonnaise Mandonguillas amb sepia -

Brochure-World of Flavors.Pdf

SZECHWAN SHRIMP OVER COCONUT RICE Ingredients 4 Servings 12 Servings SAVORING Weights Measures Weights Measures Calrose or New Variety, uncooked medium grain rice 6 oz 1 cup 1 lb 2 oz 3 cups Water 3/4 cup 2 1/4 cups Coconut milk 3/4 cup 2 1/4 cups CALIFORNIA Butter 1 tbsp 3 tbsp TO MAKE SURE YOU RE Salt 1/2 tsp 1 1/2 tsp ’ Honey 1/3 cup 1 cup USING THE FINEST CALIFORNIA RICE… Soy sauce 3 tbsp 1/2 cup Chili garlic paste 3 tbsp 1/2 cup Shrimp, large and peeled 1 lb 3 lbs RICE LOOK FOR OUR CALIFORNIA PREMIUM RICE SEAL OR CHOOSE ONE OF THESE BRANDS THROUGH YOUR AREA SUPPLIER Vegetable oil 1 tbsp 3 tbsp Bell peppers, any color, matchstick strips 3 oz 1 cup 9 oz 3 cups Carrots, matchstick strips 3 1/2 oz 1 cup 10 1/2 oz 3 cups Snow peas, strips 2 3/4 oz 1 cup 8 3/4 oz 3 cups SWEET &SAVORY PILAF Sliced green onions 1/4 cup 3/4 cup DIRECTIONS: Ingredients 4 Servings 12 Servings TM Weights Measures Weights Measures 1. To prepare rice, combine rice, water, coconut milk, butter and salt in a large pot. Bring to a boil; reduce heat and simmer, covered, Butter 1 oz 2 tbsp 3 oz 6 tbsp for 20 minutes. Remove from heat and let stand for 10 minutes. Calrose uncooked medium grain rice 7 oz 1 cup 1 lb 5 oz 3 cups 2. To prepare shrimp, whisk together honey, soy sauce and chili TM Shallots, sliced 2 oz 2 medium 6 oz 6 medium garlic paste in a large bowl. -

Sofrito's Catering Menu Please Print This Menu, Check Selections, and Email Request Or Fax to 212-754-5959

Sofrito's Catering Menu Please print this menu, check selections, and email request or fax to 212-754-5959 Appetizer / Entradas Half Tray Full Tray 10-15 16-30 Serving Serving Sofrito Famous Empanadas $2.50 each Minimum (Cheese, Beef, Chicken, Shrimp or Vegetable) 18 Mini Mofonguitos (Mini Plantain Mash Rounds) $ 7 5. $75.00 $140 .00 Rellenos de papa (Potato Puff stuffed with Ground beef) $75.00 $140.00 Bunuelos de Bacalao (Cod fish Puff) $75.00 $140.00 Mini Piononos (Sweet Plantain Stuffed w/ Ground Beef) $95.00 $175.00 Calamares Crujientes (Crispy Calamari) $100.00 $190.00 Chicharron de camaron (Crispy fried Shrimp) $120.00 $225.00 Chicharron de pollo (Crispy Adobo Chicken) $70.00 $120.00 Alcapurria (Crispy Fried Taro Root Stuffed w/ ground beef) $95.00 $175.00 Carne Frita (Fried Boneless Pork) $60.00 $110.00 Sopas/ Soup 2 Quarts 1 Gallon Sancocho $20.00 $40.00 Sopa de Pollo $20.00 $40.00 Ensaladas / Salads HalfTray Full Tray 10-15 16-30 Serving Serving Cesar Boricua with Plantain $30.00 $60.00 House Salad ( 7 Lettuce w/ House vinaigrette) $25.00 $50.00 Chopped Salad (mix green, tomatoes, red onion, chicks peas, cucumber, corn and carrot $45.00 $75.00 with honey lime vinaigrette) Seasonal Salad $45.00 $75.00 Carne y Pollo / Meat & Chicken Half Tray Full Tray 10-15 16-30 Serving Serving Chuletas De Cerdo ( Marinated Pork Chops Grilled or Fried) $80.00 $150.00 Pernil (Roast Pork) $75.00 $150.00 Pechuga De Pollo a la Parilla (Grilled Chicken Breast With Garlic Glaze) $75.00 $140.00 Churrasco (Skirt Steak) $150.00 $300.00 -

Don't Miss This Soups

Week of July 26 Monday – Friday Breakfast 7:30 am – 9:30 am Lunch 11:30 am – 1:30 pm butcher and baker: cuban, ham, roast pork, swiss, pickle, mustard on telera or grilled eggplant, hummus, spinach, tomato on ciabatta don't miss this masala: (H) chicken achari or aloo gobi, daal soup, basmati rice, naan Monday zen: shrimp lo mein or vegetable option with wok tossed vegetables weekly salad specials: southwest chicken, romaine, pico de gallo, black beans, corn, flame: chile verde slow braised pork, refried beans, kim’s spanish rice or plant-based shredded jack cheese, chipotle option ranch dressing butcher and baker: cuban, ham, roast pork, swiss, pickle, mustard on telera or grilled eggplant, hummus, spinach, tomato on ciabatta mixed greens, sun-dried tomato, quinoa, basil, heirloom tomato, cucumber, balsamic vinaigrette Tuesday zen: beef with tomato & egg or plant-based option mixed vegetables & brown rice butcher and baker: cuban, ham, roast pork, swiss, pickle, mustard on telera or grilled eggplant, hummus, spinach, tomato on ciabatta masala: (H) chicken biryani or vegetable biryani with riata zen: sam’s braised beef or plant-based option with mixed vegetables & jasmine rice Wednesday Soups flame: pizza your choice of bbq (H) chicken, onion, jalapeno or pepperoni or monday vegetable with peppers, mushroom, tomato, onion tomato basil sausage potato & kale butcher and baker: cuban, ham, roast pork, swiss, pickle, mustard on telera or grilled tuesday eggplant, hummus, spinach, tomato on ciabatta carrot ginger (H)chicken hot & sour Thursday masala: shrimp aloo curry or mattar paneer, basmati rice, daal & naan wednesday vegetarian minestrone split pea & ham butcher and baker: cuban, ham, roast pork, swiss, pickle, mustard on telera or grilled eggplant, hummus, spinach, tomato on ciabatta thursday (H) chicken orzo masala: (H) chicken paratha wrap or paneer wrap with daal soup cream of cauliflower zen: honey soy salmon or organic tofu with wok tossed vegetables & pineapple Friday friday cashew rice clam chowder vegetarian chili A.J. -

Catering Menu

621 W Carson Street NOODLE MENU Carson CA 90745 • GUISADO : BIHON, MIKI, CANTON or MIXED • $20 (1/2) • $30 (S) (310) 834-6289 • (310) 533-0907 $50 (M) • $70 (L) • SOTANGHON • www.titacelias.com • PALABOK • SWEET SPAGHETTI • $25 (1/2) • $35 (S) • $55 (M) • $75 (L) Open daily from 7am - 9pm REAL FILIPINO HOME COOKING SINCE 1990 BEEF MENU * MORCON ($20 per pound • 5 pound minimum) Rolled marinated Beed flank sheet with Red Bell Pepper, Carrots, Sausage, Pork Fat pan roasted with Spices, Onions, Tomatoes. * MECHADO Beef chunks stewed in Spices, Tomato Sauce, DESSERT MENU Pineapple Juice, Red Bell Peppers and Potatoes. * CARIOCA $1.50/stick * BUCHI $1.50/pc POCHERO Caramelized rice flour balls. Caramelized rice flour balls with red beans. Beef chunks stewed in Pork and Beans, mixed with vegetables, plantain and sweet potatoes. TURON $0.75/pc BANANA-Q $1.75/stick Banana and Jackfruit fritters. Caramelized sweet Plantains. PAN FRY BEEF BBQ RIBS Meaty Ribs fried in special Sweet and Spicy Sauce. * KALAMAY HIRIN $30 (S) * GINATA'ANG BILO-BILO $25 (S) Rice Flour in Coconut Milk sauce. $60 (L) Tropical Fruits in Coconut Milk. $50 (L) BISTEK TAGALOG Marinated thin sliced Angus Beef cooked in Soy Sauce and Onions BICO $25 (S) GINATA'ANG MONGGO $25 (S) Sticky Rice with Jackfruit. $50 (L) Red Beans and Rice Pudding. $50 (L) BEEF CALDERETA KALAMAY UBE $25 (S) BIBINGKA MALAGKIT $25 (S) Beef chunks stewed in Tomato Sauce, Spices, Onions, Cheese, Coconut Milk, Chili. Rice Flour with Coconut Milk. $50 (L) Sweet Rice topped with Coconut Jam. -

One Pot Recipes

Girl Scouts of Greater Los Angeles Sep 2012 1 Girl Scouts of Greater Los Angeles TABLE OF CONTENTS COOKING PROGRESSION ............................................................................................ 1 ONE POT RECIPES ....................................................................................................... 2 Main Dishes .................................................................................................................... 2 Arroz Con Pollo (Chicken with Rice) ............................................................................ 2 Beef Skillet Supper ...................................................................................................... 2 Camp Chili ................................................................................................................... 2 Camper‟s Chicken n‟ Dumplings .................................................................................. 3 Campfire Stew ............................................................................................................. 3 Captain‟s Specialty ...................................................................................................... 3 Casualty, Casualty, or Mess ........................................................................................ 3 Catastrophe ............................................................................................................. 3 Mess ....................................................................................................................... -

Page 1 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 965 FL 019 564 AUTHOR

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 965 FL 019 564 AUTHOR Riego de Rios, Maria Isabelita TITLE A Composite Dictionary of Philippine Creole Spanish (PCS). INSTITUTION Linguistic Society of the Philippines, Manila.; Summer Inst. of Linguistics, Manila (Philippines). REPORT NO ISBN-971-1059-09-6; ISSN-0116-0516 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 218p.; Dissertation, Ateneo de Manila University. The editor of "Studies in Philippine Linguistics" is Fe T. Otanes. The author is a Sister in the R.V.M. order. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Vocabularies/Classifications/Dictionaries (134)-- Dissertations/Theses - Doctoral Dissertations (041) JOURNAL CIT Studies in Philippine Linguistics; v7 n2 1989 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Creoles; Dialect Studies; Dictionaries; English; Foreign Countries; *Language Classification; Language Research; *Language Variation; Linguistic Theory; *Spanish IDENTIFIERS *Cotabato Chabacano; *Philippines ABSTRACT This dictionary is a composite of four Philippine Creole Spanish dialects: Cotabato Chabacano and variants spoken in Ternate, Cavite City, and Zamboanga City. The volume contains 6,542 main lexical entries with corresponding entries with contrasting data from the three other variants. A concludins section summarizes findings of the dialect study that led to the dictionary's writing. Appended materials include a 99-item bibliography and materials related to the structural analysis of the dialects. An index also contains three alphabetical word lists of the variants. The research underlying the dictionary's construction is