Videogames, War and Operational Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Falcon 3 Tactics Manual

The Falcon 3.0 Manual Tactics Section - Introduction to the Geometry of Air Combat by Ed "Skater" Lynch For those of you that are "old salts" when it comes to flight sims, and for those of you that are new to flight sims, this article should be of some value to you. This is largely a reprint from the manual of one of the best combat flight sims ever released. Spectrum Holobyte's Falcon 3.0 was indeed the father of all modern, "realistic" combat flight sims. The F3 manual was one hell of a paper weight. Weighing in at something like seven pounds, the F3 manual was jam packed with information on flying the sim, and the usage of tactics, and the deployment of weapons and the employment of the aircraft. Here is a little jewel from the tactics section. Enjoy! Credit goes to Microprose / Hasbro Interactive, Spectrum Holobyte, and the Falcon 3.0 team. Introduction to the Geometry of Air Combat In order to become a great fighter pilot, you must perform great BFM. Now, in order to perform BFM, a fighter pilot must understand his positional relationship to the target from three perspectives: positional geometry, attack geometry and the weapons envelope. Positional Geometry Angle-off, range and aspect angle are terms used in BFM discussions to describe the relative advantage or disadvantage that one aircraft has in relation to another. Angle-Off Angle-Off is the difference, measured in degrees, between your heading and the bandit's. This angle provides information about the relative fuselage alignment between the pilot's jet and the bandit's. -

Video Game Collection MS 17 00 Game This Collection Includes Early Game Systems and Games As Well As Computer Games

Finding Aid Report Video Game Collection MS 17_00 Game This collection includes early game systems and games as well as computer games. Many of these materials were given to the WPI Archives in 2005 and 2006, around the time Gordon Library hosted a Video Game traveling exhibit from Stanford University. As well as MS 17, which is a general video game collection, there are other game collections in the Archives, with other MS numbers. Container List Container Folder Date Title None Series I - Atari Systems & Games MS 17_01 Game This collection includes video game systems, related equipment, and video games. The following games do not work, per IQP group 2009-2010: Asteroids (1 of 2), Battlezone, Berzerk, Big Bird's Egg Catch, Chopper Command, Frogger, Laser Blast, Maze Craze, Missile Command, RealSports Football, Seaquest, Stampede, Video Olympics Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 Atari Video Game Console & Controllers 2 Original Atari Video Game Consoles with 4 of the original joystick controllers Box 2 Atari Electronic Ware This box includes miscellaneous electronic equipment for the Atari videogame system. Includes: 2 Original joystick controllers, 2 TAC-2 Totally Accurate controllers, 1 Red Command controller, Atari 5200 Series Controller, 2 Pong Paddle Controllers, a TV/Antenna Converter, and a power converter. Box 3 Atari Video Games This box includes all Atari video games in the WPI collection: Air Sea Battle, Asteroids (2), Backgammon, Battlezone, Berzerk (2), Big Bird's Egg Catch, Breakout, Casino, Cookie Monster Munch, Chopper Command, Combat, Defender, Donkey Kong, E.T., Frogger, Haunted House, Sneak'n Peek, Surround, Street Racer, Video Chess Box 4 AtariVideo Games This box includes the following videogames for Atari: Word Zapper, Towering Inferno, Football, Stampede, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ms. -

The Foundations of Song Bird

Running head: THE FOUNDATIONS OF SONG BIRD GENDER SPECTRUM NEUTRALITY AND THE EFFECT OF GENDER DICHOTOMY WITHIN VIDEO GAME DESIGN AS CONCEPTUALIZED IN: THE FOUNDATIONS OF SONG BIRD A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY CALEB JOHN NOFFSINGER DR. MICHAEL LEE – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2018 THE FOUNDATIONS OF SONG BIRD 2 ABSTRACT Song Bird is an original creative project proposed and designed by Caleb Noffsinger at Ball State University for the fulfillment of a master’s degree in Telecommunication: Digital Storytelling. The world that will be established is a high fantasy world in which humans have risen to a point that they don’t need the protection of their deities and seek to hunt them down as their ultimate test of skill. This thesis focuses more so on the design of the primary character, Val, and the concept of gender neutrality as portrayed by video game culture. This paper will also showcase world building, character designs for the supporting cast, and examples of character models as examples. The hope is to use this as a framework for continued progress and as an example of how the video game industry can further include previously alienated communities. THE FOUNDATIONS OF SONG BIRD 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 4 Chapter 1: Literature Review. 8 Chapter 2: Ludology vs. Narratology . .14 Chapter 3: Song Bird, the Narrative, and How I Got Here. 18 Chapter 4: A World of Problems . 24 Chapter 5: The World of Dichotomous Gaming: The Gender-Neutral Character . -

A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo's Hardware and Software

A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo’s Hardware and Software History Marilyn Sugiarto A Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2017 © Marilyn Sugiarto, 2017 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By Marilyn Sugiarto Entitled A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo’s Hardware and Software History and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: __________________________________ Chair Dr. Maurice Charland __________________________________ Examiner Dr. Fenwick McKelvey __________________________________ Examiner Dr. Elizabeth Miller __________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Mia Consalvo Approved by __________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director __________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty Date __________________________________________________ iii Abstract A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo’s Hardware and Software History Marilyn Sugiarto Since 1985, the American video game market and its consumers have acknowledged the significance of Nintendo on the broader development of the industry; however, the place of Nintendo in the North American -

Nintendo Game Boy

Nintendo Game Boy Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 4 in 1: #1 Sachen 4-in-1 Fun Pak Interplay Productions 4-in-1 Funpak: Volume II Interplay Productions Addams Family, The Ocean Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt Ocean Adventure Island II: Aliens in Paradise, Hudson's Hudson Soft Adventure Island II: Aliens in Paradise, Hudson's: Electro Brain Rerelease Electro Brain Adventure Island, Hudson's Hudson Soft Adventure Island, Hudson's: Electro Brain Rerelease Electro Brain Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends, The THQ Adventures of Star Saver, The Taito Aerostar VIC Tokai Aerostar: Sunsoft Rerelease Sunsoft Aladdin, Disney's Virgin Interactive Aladdin, Disney's: THQ Rerelease THQ Alfred Chicken Mindscape Alien vs Predator: The Last of His Clan Activision Alien³ LJN All-Star Baseball '99 Acclaim Alleyway Nintendo Altered Space Sony Imagesoft Amazing Penguin Natsume Amazing Spider-Man 3, The: Invasion of the Spider-Slayers LJN Amazing Spider-Man, The LJN Amazing Tater Atlus Animaniacs Konami Arcade Classic #1: Asteroids & Missile Command Nintendo Arcade Classic #2: Centipede & Millipede Nintendo Arcade Classic No. 3: Galaga & Galaxian Nintendo Arcade Classic No. 4: Defender / Joust Nintendo Asteroids Accolade Atomic Punk Hudson Soft Attack of the Killer Tomatoes THQ Avenging Spirit Jaleco Balloon Kid Nintendo Barbie Game Girl Hi-Tech Express Bart Simpson's Escape From Camp Deadly Acclaim Baseball Nintendo Bases Loaded Jaleco Batman Sunsoft Batman Forever Acclaim Batman: Return of the -

1 Pitch Proposals Company: Spectrum Holobyte Project: Top Gun

Pitch Proposals Company: Spectrum HoloByte Project: Top Gun Platform/Format: Print Description: This pitch was presented to Nintendo and accepted for co-development on the gaming platform that became the Nintendo-64. In addition to introducing the overall concept for the game, it presented the basic game mechanics, and the risks associated with development. Like film, the risks in game development can be fairly well qualified up front. What's the game engine? Who is on the development team? Can we tie it to a valuable license? Unlike film, however, the audience demands technical innovation in each offering, so there's a culture of risk-taking in games that doesn't seem to pervade the film industry. Experienced developers know that there must be something substantial in terms of technology, personnel, and risk management behind the pitch. Notes: Use the Jump to... menu below to access individual chapters. Top Gun High Concept For the Nintendo Ultra64 September 8, 1994 High Concept: You strap into an F-14 Tomcat as Maverick, ace of Top Gun. The Cadre has struck again, this time dropping a diplomatic transport into the Sea of Japan. You and the Top Gun team have scrambled to respond in a game that combines the most polished flight sim technology and network play with rippin’ fast dogfighting for the Ultra64 consoles. Flaps are down; you’re cleared for take-off! You’re the best of the best, said the commanding officer. And it’s time to prove it. Welcome to Top Gun, the elite training academy for the Navy’s best fighter pilots. -

Android Tetris Free Download Android Tetris Free Download

android tetris free download Android tetris free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66b57908c8dbc447 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Tetris. Tetris -- the foundation for most modern puzzle games, and also one of the most highly acclaimed video games of all times -- has done it again and reinvented itself for smartphones. This time around it brings a slight twist to standard gameplay, making for an even more fluid experience on your Android. Thanks to revamped controls, rather than securing where your tetris blocks fall, your aim switches over to choosing from a set list of spots they can fall into. That makes the overall experience a lot less mentally taxing without deviating too much from standard play. As you've come to expect from almost any Tetris game, this new version includes several different game modes for you to choose from. Marathon and Galaxy Tetris are the two main modalities you can play in, and where you'll want to set the high score. -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power. -

Hardware Manufacturers and Software Publishers' Playing-To-Win

Theory and Evidence PLAYING THE GAME: Hardware manufacturers and software publishers’ playing-to-win strategies within the video game industry by Rebecca Kleinstein An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2005 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Sam Craig Professor Adam Brandenburger Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisors Abstract This paper presents an overview and analysis of the explosive growth and evolution of the home video game industry over successive generations of hardware consoles. The analytical tools of Game Theory, ‘Value Nets’ and ‘Added Value,’ are used to examine the duality of both the complementary and the competitive aspects of the relationships between video game hardware (console) manufacturers and third-party software publishers. This research has chronicled the emergence of the third-party publishers from an essentially underappreciated commodity in the 8-bit generation to an industry-leading powerhouse on near-equal footing with the hardware manufacturers in the current 128-bit generation. 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. What are video games? ............................................................................................................ 4 3. Who are the ‘players’ in the video game industry? .............................................................. -

Game Review: Sid Meier's Civilization

Game Review: Sid Meier's Civilization next up previous Next: Identification Game Review: Sid Meier's Civilization Brian Palmer ● Identification ● Story-line ● Features ● Design ● Success ● Bibliography ● About this document ... Brian Palmer 2001-02-22 http://www.stanford.edu/~bpalmer/review/ [2/23/2001 3:19:18 PM] Identification next up previous Next: Story-line Up: Game Review: Sid Meier's Previous: Game Review: Sid Meier's Identification The subject of this review is Sid Meier's Civilization (hereafter Civilization or Civ), a game released in 1991 by MicroProse as an adaption of Avalon Hill's board game Civilization. The computer game was a smashing success and has been a gaming classic ever since. The most prominent designer of the game, Sid Meier, was also the programmer. The other chief designer was Bruce Shelley; but more than a score of other people helped with the game. A complete list of the game credits is given in [10]. Brian Palmer 2001-02-22 http://www.stanford.edu/~bpalmer/review/node1.html [2/23/2001 3:19:59 PM] Story-line next up previous Next: Features Up: Game Review: Sid Meier's Previous: Identification Story-line Civilization has elements of historical simulation within it, but is predominantly a ``4X'' turn-based strategy game. The term ``4X'' is explained by [1] as standing for the phrase ``eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, and eXterminate'' -- these four verbs provide a sketchy overview of the game. The player begins the game viewing a map with control over one or more `settler' units (a unit is a small figure which can be moved around the world map representing a specialized group of people). -

The Civilization Series and Sid Meier's Legacy

Civilization: Sid Meier’s Legacy. Nathan Mintz March 10, 2003. Case Study. From his humble origins as the co-founder of a garage startup, Sid Meier has grown to become a game industry superstar. Most prominent in his success has been the Civilization series, which has sold over five million copies in its half a dozen incarnations.1 The success of the Civilization series can be attributed to Sid’s unique philosophy for game design. Sid’s emphasis on interactivity over flashy animation, sound effects and action sequences makes him truly stand apart as a game designer. It is this model of game design that makes Civilization so unique and was the vital lynchpin in its success. In the beginning… Sid’s successful career as a game designer began in 1982 when a younger Sid and future business partner Bill Stealey were both working for General Instruments Corporation. Excited by their conversations about video games, they decided to come together and founded Microprose, one of many basement computer companies founded in the early 1980s.2 There first release, F-15 Strike Eagle, a flight simulator, came out later that year and went on to sell over one million copies worldwide.3 This initial success gave Microprose what it needed to take off: over the next seven years it would release eight new games including Silent Service, Sid Meier’s Pirates!, Red Storm Rising and F- 19 stealth fighter.4 Picture on title page taken from the “Civ III: Play The World” website available: http://www.civ3.com/ptw_screenshots.cfm. 1 “Firaxis Games: About Sid Meier” available: http://www.firaxis.com/company_sid.cfm. -

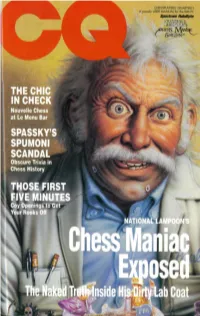

MANUAL for Ttie IBM PC Spectrum Hotobyte

CHESSPLAYERS' QUARTERLY A parody USER MANUAL for ttie IBM PC Spectrum HotoByte THE CHI IN CHEC Nouvelie Chess at Le Menu Bar SPASSKY'S SPUMONI SCANDAL Obscure Trivia in Chess History THOSE FIRS FIVE MINUTES Coy Openings to Your Rooks letter from the chairman LISTEN TO this... The new American Renaissance has leapt upon us, jaws agape. We have a President who was in the vicinity of the Great White North plunge software dope and wails on the sax. Our Mighty criminals naked through holes in the War Machine is turning aside its polar ice cap. I've witnessed Australian craving for destruction, and we've aborigines feed the villains to the wild learned to embrace our former enemies. dingos of the Outback. Piece by piece. South American rainforests are being Definitely not tres chic. preserved to give us that needed breath We'll continue to produce quality of fresh air. You, as a member of this software as long as you pay for it. great nation, have the opportunity to Without your cash, we fail. The make a profound difference. Stop industry fails. Soon there may be no software piracy. one left to invent that spreadsheet, It's been documented that software computerize your taxes, to create Tetris. pirates in foreign countries are Think about it. If you want to talk, subjected to penalties horrible if caught. we'll be there. Give us a call. We'd like In parts of Africa, offenders are strung to hear from you. spread-eagle between two trees to be See you on the funny pages.