Moving the Race Conversation Forward Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESTAURANT Italian Restaurant CLEANING Performance & Delicatessen Page 3 Page 9 Page 12 Page 13

WILL GO Buon Appetito FREE RESTAURANT Italian Restaurant CLEANING Performance & Delicatessen Page 3 Page 9 Page 12 Page 13 4141stst TV AnniversaryAnniversary A WEEKLY MAGAZINE June 24 - June 30, 2017 JAN.1976JAN.1976 Call 917-232-5501 www.TVTALKMAG.com JAN. 2017 Email: [email protected] Refer a Friend to our Car Wash Club FULL SERVICE & Receive One Month of Car Wash Club FREE Only $8.00 (Offer valid for members of 6 months or more) DETAIL Regularly $11.96 SPECIALS Includes: Exterior Wash • Vacuum CAR WASH Inside Windows • Dust Dash Console • QUICK LUBE Offer Valid Tuesdays & Wednesdays Only Not to be combined with any other offer. • AUTO REPAIR With this coupon only. Expires 6/30/17 1505 Kennedy Blvd. (at City Line) Jersey City, NJ • Call 201-434-3355 Open 7 Days Mon.-Sat. 8 AM-6 PM • Sun. 8 AM-4 PM • All Major Credit Cards Accepted A tale of two women as Ghost faces DAYTIME TV WEEKDAYS prison in Season 4 of ‘Power’ AFTERNOON WILL GO CLEANING PIPELINE By George Dickie themselves. So that sort of vulnerable, in- 2:00 ^ The Talk By Jay Bobbin love girl that was starting to bloom with $ Steve Harvey For three seasons on Starz’s “Power,” % Harry Q: I was very impressed with Navi, who Ghost ... she sort of slings back and she _ drug kingpin-turned-nightclub maven Who Wants to Be a Millionaire CARPET, RUGS played Michael Jackson in a recent Lifetime seals herself against him because she al- ( Arthur movie. What’s his background? — Jean Price, James “Ghost” St. -

“Facebook Is Hurting People at Scale”: Mark Zuckerberg's

“Facebook Is Hurting People At Scale”: Mark Zuckerberg’s Employees Reckon With The Social Network They’ve Built As the US heads toward a crucial and contentious presidential election, the world's largest social network is facing an unprecedented cultural crisis. By Ryan Mac and Craig Silverman Posted on July 23, 2020, at 11:37 a.m. ET On July 1, Max Wang, a Boston-based software engineer who was leaving Facebook after more than seven years, shared a video on the company’s internal discussion board that was meant to serve as a warning. “I think Facebook is hurting people at scale,” he wrote in a note accompanying the video. “If you think so too, maybe give this a watch.” Most employees on their way out of the “Mark Zuckerberg production” typically post photos of their company badges along with farewell notes thanking their colleagues. Wang opted for a clip of himself speaking directly to the camera. What followed was a 24-minute clear-eyed hammering of Facebook’s leadership and decision-making over the previous year. The video was a distillation of months of internal strife, protest, and departures that followed the company’s decision to leave untouched a post from President Donald Trump that seemingly called for violence against people protesting the police killing of George Floyd. And while Wang’s message wasn’t necessarily unique, his assessment of the company’s ongoing failure to protect its users — an evaluation informed by his lengthy tenure at the company — provided one of the most stunningly pointed rebukes of Facebook to date. -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

1 United States District Court

Case 1:16-cv-08215 Document 1 Filed 10/20/16 Page 1 of 17 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK COLOR OF CHANGE and CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS, Plaintiffs, v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, and FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 1. This is an action under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. §§ 552 et seq., seeking declaratory, injunctive, and other appropriate relief to compel the Defendants, the United States Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) (collectively “Defendants”), to produce agency records that have been improperly withheld from Plaintiffs, Color of Change (“COC”) and the Center for Constitutional Rights (“CCR”) (collectively “Plaintiffs”). 2. Plaintiffs’ submitted a FOIA request to Defendants on July 5, 2016, seeking records related to federal government surveillance and monitoring of protest activities related to the Movement for Black Lives (“MBL”). See July 5, 2016 FOIA Request Letter from COC and CCR (“Request”), attached as Exhibit A. The Request documented the compelling and urgent need for public disclosure of information related 1 Case 1:16-cv-08215 Document 1 Filed 10/20/16 Page 2 of 17 to federal responses to public protests. Plaintiffs’ sought expedited processing and a fee waiver. 3. Police violence, criminal justice, and racial inequity are now the subjects of an impassioned national, political debate. MBL has played a significant role in bringing this discussion to the forefront by holding demonstrations in cities throughout the country, often in response to deadly police shootings of Black people. -

BRANDI COLLINS-DEXTER Senior Campaign Director, Color of Change

TESTIMONY OF BRANDI COLLINS-DEXTER Senior Campaign Director, Color Of Change Before the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology and the Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce United States House Committee on Energy and Commerce Hearing on “A Country in Crisis: How Disinformation Online is Dividing the Nation.” June 24, 2020 Good morning Chairwoman Schakowsky, Subcommittee Chairman Mike Doyle, and Members of the subcommittees. I am Brandi Collins-Dexter, Senior Campaign Director at Color of Change. We are the country’s largest racial justice organization, with currently seven million members taking actions in service of civil rights, justice, and equity. For nearly a year, I have been a research fellow at Harvard Kennedy's Shorenstein Center, working on documenting racialized disinformation campaigns. Freedom of expression and the right to protest are often uplifted as core American values. In schools and in the media, we’re told that what makes America “great” can be found in our history of fighting in the name of freedom: from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War to the March on Washington. But often the celebration or condemnation of protest is contingent on who is doing the protesting, as well as how and when they choose to protest. This often dictates whether that protest is seen as a lawful exercise of First Amendment rights, revolutionary, counterproductive, a lawless riot, or “an orgy of violence.” 1 Indeed, contemporary local journalists covering the March on Washington back then speculated that it would be impossible to bring more than “100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incidents and possibly rioting.”2 Only in hindsight is that moment universally accepted as a positive catalyst for change. -

Philanthropy New York 38Th Annual Meeting Program FINAL

3 8 T H A N N U A L M E E T I N G THE POWER OF PARTICIPATION J U N E 1 6 , 2 0 1 7 • N E W Y O R K , N Y TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Message from the President and Board Chair 2 Board Members 3 Board Candidates 4 Annual Meeting Program 7 Tweet Cheat Sheet 8 Speakers and Presenters 17 Related PSO Information 21 Philanthropy New York Staff 23 Philanthropy New York Committees, Working Groups and Networks Special thanks to JPMorgan Chase & Co., our generous host for the Philanthropy New York 38th Annual Meeting MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT AND BOARD CHAIR A Continuation and a New Beginning Welcome to Philanthropy New York’s 38th Annual Meeting: The Power of Participation. Today is both a continuation and a new beginning for Philanthropy New York. Over the years, we have presented many programs on issues related to democratic participation and showcased the initiatives of funders who have supported both ground-level organizing and systematic reforms. As we all know, the conversations around the challenges to our democratic system did not begin with a single election. The flaws of our electoral systems, voter disenfranchisement and the long simmering erosion of public trust in government and media have been part of the American landscape for some time. While the diagnosis of what ails our democracy has been discussed for years, the enthusiasm and consensus around taking action has grown significantly since the last national election. Looking at how attitudes around race, gender, and immigration, to name some of the core issues, have combined with inadequate or erroneous knowledge, to influence our democracy is now a national conversation. -

Record V16.19

Stacks of history Inside this edition: April ‘Middle Tennessee Record’ Intercultural event draws CNN anchor, page 2 celebrates MTSU’s library legacy Celebrate excellence with president, page 5 see page 3 Exchange student is going places, page 8 Back ffrom the ffiielld,, page 6 a publication for the Middle Tennessee State University community April 7, 2008 • Vol. 16/No. 19 Women’s sports Learn more about new facilities policy by Tom Tozer The WebViewer Calendar dis- Conference Room, Learning Resource at MTSU marks plays event information from R25, an Center computer labs and the eed your space? The event-management software system. Campus Recreation Center. With the proud heritage Resource25 WebViewer, R25 and WebViewer were implement- addition of other schedulers and facil- N MTSU’s master calendar, is ed for academics in 1999. Gradually, ities to R25, scheduling events on nonacademic spaces were added. campus has become more diverse and by Alesha Brown an easily accessible place to find it— and to learn what, when and where comprehensive. This expansion of events and classes are happening schedulers has led to some changes in resh from Women's History throughout the campus. The calendar SSaavvee tthhee ddaatteess!! the policies and procedures for sched- uling space on campus. Month celebrations, and is found at www.mtsu.edu/webviewer. Apriill 16,, 1::30 p..m.. F with the NCAA Women’s Once you have this information Event Coordination has played a Basketball Tournament set for and know what spaces would be Apriill 29,, 10 a..m.. crucial role in working with the cam- April 6-8, spring is a timely season appropriate for your needs, you can pus community, university adminis- to think about the role and history visit the Event Coordination Web site tration and the Tennessee Board of of women’s sports. -

Shanlon “Shan” Wu Is a Former Federal Prosecutor Who Served in The

[email protected] _____________________________________________________________________ Legal analysis & commentary delivered with clarity, savvy, & humor. Shan excels at breaking down complex legal & political topics into plain language with thought-provoking points of view. He is a CNN legal analyst, appears regularly on National Public Radio & his writing is regularly published in national print & digital platforms. Shanlon “Shan” Wu is a former federal prosecutor who served in the Clinton Administration as Counsel to Attorney General Janet Reno and is now a nationally known criminal defense & college student defense lawyer. He appears regularly on CNN, National Public Radio, podcasts and streaming media, offering insightful, often humorous analysis on issues including the Trump impeachments, Mueller Russian probe, sex crimes and politics inside the Department of Justice. Recent notable cases include his representation of Rick Gates – co-defendant with Paul Manafort – in the Mueller Russian probe as well as the case of Mimi Groves – a University of Tennessee cheerleader who was victimized by “cancel culture.” Shan’s writing on topics such as racism in the law, the Mid-Term Elections, sexual assault, and the Harvard Affirmative Action lawsuit brought by Asian American students, reflects a style honed by a MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College and an English Literature degree from Vassar College. His work has appeared in CNN Opinions, The Washington Post, The Hill, xoJane, and The Daily Beast. As the only child of Chinese immigrants who were political refugees, Shan brings a strong Asian American and minority perspective to the political and legal issues of the day. From his days of being the only Asian amateur boxer in tournaments and the first Asian American to win Best Advocate as both a first-year and upper-classman at Georgetown law school, to now being one of the only Asian lawyers on national television - Shan has always blazed his own trail. -

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S. Security State A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Mia Louisa Fischer IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Mary Douglas Vavrus, Co-Adviser Dr. Jigna Desai, Co-Adviser June 2016 © Mia Louisa Fischer 2016 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family back home in Germany for their unconditional support of my academic endeavors. Thanks and love especially to my Mom who always encouraged me to be creative and queer – far before I knew what that really meant. If I have any talent for teaching it undoubtedly comes from seeing her as a passionate elementary school teacher growing up. I am very thankful that my 92-year-old grandma still gets to see her youngest grandchild graduate and finally get a “real job.” I know it’s taking a big worry off of her. There are already several medical doctors in the family, now you can add a Doctor of Philosophy to the list. I promise I will come home to visit again soon. Thanks also to my sister, Kim who has been there through the ups and downs, and made sure I stayed on track when things were falling apart. To my dad, thank you for encouraging me to follow my dreams even if I chased them some 3,000 miles across the ocean. To my Minneapolis ersatz family, the Kasellas – thank you for giving me a home away from home over the past five years. -

Industry Response to Social Justice

INDUSTRY RESPONSE TO SOCIAL JUSTICE A+E Networks • A+E Networks has produced “The Time Is Now: Race and Resolution,” which aired across all A+E networks in partnership with the NAACP and OZY (an international media and entertainment company which describes its mission as helping curious people see a broader and a bolder world). o This important conversation features influential social justice voices discussing the ways systemic racism, implicit bias, and economic inequality are afflicting our nation, and pathways forward to help achieve lasting change. AMC Networks • AMC Networks has invited each of its 1,000 U.S. employees to identify charitable organizations that tackle issues related to racial inequality to receive a $1,000 donation from the company (so, $1,000 from EACH employee = about $1 million). o The company’s goal is to have the donations be spread among organizations that employees already work with or support in other ways. (AMC Networks took a similar approach earlier this year in giving employees $1,000 apiece to donate to coronavirus-related relief efforts.) • The company also gave employees June 4 as a day off for a “Day of Reflection.” • The company also observed a nearly nine-minute blackout on June 4 across its five cable channels — AMC, SundanceTV, IFC, We TV and BBC America; and, it hosted a company town hall to discuss social justice and inequality issues on June 5. Comcast • Comcast Corp. unveiled a $100 million plan to support social justice and equality. o Comcast Chief Executive Brian Roberts said that the company would set aside $75 million in cash and $25 million in advertising inventory to fight injustice against “any race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation or ability.” o The funds and ad space will be distributed over the next three years. -

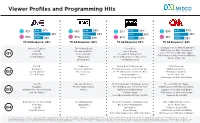

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits 42% 18-34 27% 55% 18-34 28% 33% 18-34 28% 59% 18-34 34% 35-54 41% 35-54 39% 35-54 43% 35-54 38% 58% 45% 55-65+ 32% 55-65+ 33% 67% 55-65+ 28% 41% 55-65+ 28% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 60% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 64% America’s Top Dog The Walking Dead Below Deck The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD Two and a Half Men Project Runway CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera State of the Union With Jake Tapper Alaska PD Better Call Saul Below Deck Sailing Yacht Q1 CNN Newsroom With Fredricka Whitfield Live PD: Wanted Talking Dead The Real Housewives of New Jersey Cuomo Prime Time Breaking Bad Vanderpump Rules Live PD Tombstone Below Deck Mediterranean CNN Newsroom Biography Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives of New York City CNN Newsroom Live Q2 Live PD: Wanted Better Call Saul The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Erin Burnett OutFront Live PD: Rewind Movies Vanderpump Rules Cuomo Prime Time Below Deck Sailing Yacht CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera Live PD Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives Of Orange County The Lead With Jake Tapper Biography Fear the Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin Q3 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On Movies Below Deck Mediterranean Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD: Wanted Southern Charm CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera The Real Housewives Of New York City Anderson Cooper 360 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On The Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Orange County CNN Tonight With Don Lemon Court Cam Talking Dead Below Deck Mediterranean Cuomo Prime Time Q4 Live PD Movies Below Deck Anderson Cooper 360 Live PD: Wanted Project Runway Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Watch What Happens Live With Andy Cohen CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin 1 Percentage of network viewers that have seen/heard a TV ad in the last 12 months that has led them to take action as defined as clicking on a banner ad, doing an internet search, going to the advertisers website, buying the product advertised or calling/visiting the advertiser. -

East Europe Tour Fails at Once Winning Iran European Heavyweights Criticize Warsaw Conference Back to His Side: POLITICS TEHRAN — U.S

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 20,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13327 Wednesday FEBRUARY 13, 2019 Bahman 24, 1397 Jumada Al thani 7, 1440 Tehran: Bolton U.S. seeking to repeat ACL: Iran’s Saipa down Troupes from 12 suffering from chronic Syrian scenario in Minerva Punjab at countries competing in delusion about Iran 2 Latin America 2 Preliminary Stage 2 15 Fajr theater festival 16 See page 2 Iran 82% self-sufficient in producing foodstuff ECONOMY TEHRAN — Some 82 current year (which ends on March 20, deskpercent of Iran’s food- 2019). stuff needs is being supplied by domestic In addition to supplying the domestic producers, Tasnim news agency reported needs, foodstuff account for a significant quoting an agricultural official. part of Iran’s non-oil exports. According to Deputy Agriculture Dairy products, sweets, saffron, tomato Minister Abbas Keshavarz, the coun- paste, juices and concentrates, animal food, try’s self-sufficiency rate in wheat pro- poultry and aquaculture, yeast, pasta, as East duction has increased from 65 percent in well as wheat flour and potato products the Iranian calendar year of 1392 (March are some of the main items exported from 2013-March 2014) to 105 percent in the Iran to the world markets. Great opportunities for Japanese Europe investment in Iran: Larijani POLITICS TEHRAN — Iranian a meeting with Chuichi Date, speaker of deskMajlis Speaker Ali Lar- Japan’s House of Councilors. ijani who was on tour of Tokyo proposed on Larijani said it is essential for the two Tuesday that there are great opportunities countries to take more steps in line with for Japan to invest in Iran.