Proposal for a Bangla (Or Bengali) Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Bengali Keyboar

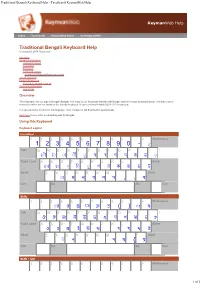

Traditional Bengali Keyboard Help - Tavultesoft KeymanWeb Help Keyman Web Help Index Tavultesoft KeymanWeb Demo Get KeymanWeb Traditional Bengali Keyboard Help Keyboard © 2008 Tavultesoft Overview Using this Keyboard Keyboard Layout Quickstart Examples Keyboard Details Complete Keyboard Reference Chart Troubleshooting Further Resources Related Keyboard Layouts Technical Information Authorship Overview This keyboard lets you type in Bengali (Bangla). It is easy to use for people familiar with Bengali and the Inscript keyboard layout. It includes some characters which are not found on the Inscript keyboard. It uses a normal English (QWERTY) keyboard. If a special font is needed for this language, most computers will download it automatically. Click here to see other keyboard layouts for Bengali. Using this Keyboard Keyboard Layout Unshifted ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Backspace 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - ◌ Tab Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ Caps Lock A S D F G H J K L ; ' Enter ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ Shift Z X C V B N M , . / Shift ◌ , . Ctrl Alt Alt Ctrl Shift ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Backspace ◌ !" # $ ( ) ◌% & Tab Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ ' ( ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 Caps Lock A S D F G H J K L ; ' Enter 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 : ; < Shift Z X C V B N M , . / Shift ◌= > ? " { @ Ctrl Alt Alt Ctrl Shift + Ctrl ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Backspace 1 of 5 Traditional Bengali Keyboard Help - Tavultesoft KeymanWeb Help Tab Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ Caps Lock A S D F G H J K L ; ' Enter Shift Z X C V B N M , . -

Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM Journal Homepage

Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology vol. 16. n. 1 (2020) 125-132 – ISSN 1973 – 2880 Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM journal homepage: http://www.antrocom.net Literacy Trends and Differences of Scheduled Tribes in West Bengal:A Community Level Analysis Sarnali Dutta1 and Samiran Bisai2 1Research Scholar, 2Associate Professor. Department of Anthropology & Tribal Studies, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal, India. Corresponding author: [email protected] keywords abstract Census data, India, Literacy, The present paper is based entirely on secondary sources of information, mainly drawn Tribal, West Bengal from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses of India and West Bengal. In this paper, an attempt has been made to analyse the present literacy trends of the ethnic communities of West Bengal, and comparing the data over a decade (2001 – 2011). The difference between male and female has also been focused. The fact remains that a large number of tribal women might have missed educational opportunities at different stages and in order to empower them varieties of skill training programmes have to be designed and organised. Implementation of systematic processes like Information Education Communication (IEC) should be done to educate communities. Introduction The term, tribe, comes from the word ‘tribus’ which in Latin is used to identify a group of persons forming a community and claiming descent from a common ancestor (Fried, 1975). Literacy is an important indicator of development among ethnic communities. According to Census, literacy is defined to be the ability to read and write a simple sentence in one’s own language understanding it; it is in this context that education has to be viewed from a modern perspective. -

75 Characters Maximum

Kannada Script LGR Proposal Introduction, Current Analysis and Next Steps Dr. U.B. Pavanaja NBGP F2F Meeting, Colombo 14 December 2017 | 1 Agenda 1 2 3 Introduction to Repertoire Analysis Within Script Kannada Script Variants 4 5 6 Cross-Script WLE Rules Current Status and Variants Next Steps for Completion | 2 Introduction to Kannada Script Population – there are about 60 million speakers of Kannada language which uses Kannada script. Geographical area - Kannada is spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka State of India. It is also spoken by significant linguistic minorities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Goa and abroad Languages written in Kannada script – Kannada, Tulu, Kodava (Coorgi), Konkani, Havyaka, Sanketi, Beary (byaari), Arebaase, Koraga | 3 Classification of Characters Swaras (vowels) Letter ಅ ಆ ಇ ಈ ಉ ಊ ಋ ಎ ಏ ಐ ಒ ಓ ಔ Vowel sign/ N/Aಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ matra Yogavahas In Kannada, all consonants Anusvara ಅಂ (vyanjanas) when written as ಕ (ka), ಖ (kha), ಗ (ga), etc. actually have a built-in vowel sign (matra) Visarga ಅಃ of vowel ಅ (a) in them. | 4 Classification of Characters Vargeeya vyanjana (structured consonants) voiceless voiceless aspirate voiced voiced aspirate nasal Velars ಕ ಖ ಗ ಘ ಙ Palatals ಚ ಛ ಜ ಝ ಞ Retroflex ಟ ಠ ಡ ಢ ಣ Dentals ತ ಥ ದ ಧ ನ Labials ಪ ಫ ಬ ಭ ಮ Avargeeya vyanjana (unstructured consonants) ಯ ರ ಱ (obsolete) ಲ ವ ಶ ಷ ಸ ಹ ಳ ೞ (obsolete) | 5 Repertoire Included-1 Sr. Unicode Glyph Character Name Unicode Indic Ref Widespread No. Code General Syllabic use ? Point Category Category [Yes/No] 1 0C82 ಂ KANNADA SIGN ANUSVARA Mc Anusvara Yes 2 0C83 ಂ KANNADA SIGN VISARGA Mc Visarga Yes 3 0C85 ಅ KANNADA LETTER A Lo Vowel Yes 4 0C86 ಆ KANNADA LETTER AA Lo Vowel Yes 5 0C87 ಇ KANNADA LETTER I Lo Vowel Yes 6 0C88 ಈ KANNADA LETTER II Lo Vowel Yes 7 0C89 ಉ KANNADA LETTER U Lo Vowel Yes 8 0C8A ಊ KANNADA LETTER UU Lo Vowel Yes KANNADA LETTER VOCALIC 9 0C8B ಋ R Lo Vowel Yes 10 0C8E ಎ KANNADA LETTER E Lo Vowel Yes | 6 Repertoire Included-2 Sr. -

A Case Study on Dhallywood Film Industry, Bangladesh

Research Article, ISSN 2304-2613 (Print); ISSN 2305-8730 (Online) Determinants of Watching a Film: A Case Study on Dhallywood Film Industry, Bangladesh Mst. Farjana Easmin1, Afjal Hossain2*, Anup Kumar Mandal3 1Lecturer, Department of History, Shahid Ziaur Rahman Degree College, Shaheberhat, Barisal, BANGLADESH 2Associate Professor, Department of Marketing, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, BANGLADESH 3Assistant Professor, Department of Economics and Sociology, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, BANGLADESH *E-mail for correspondence: [email protected] https://doi.org/10.18034/abr.v8i3.164 ABSTRACT The purpose of the study is to classify the different factors influencing the success of a Bengali film, and in this regard, a total sample of 296 respondents has been interviewed through a structured questionnaire. To test the study, Pearson’s product moment correlation, ANOVA and KMO statistic has been used and factor analysis is used to group the factors needed to develop for producing a successful film. The study reveals that the first factor (named convenient factor) is the most important factor for producing a film as well as to grab the attention of the audiences by 92% and competitive advantage by 71%, uniqueness by 81%, supports by 64%, features by 53%, quality of the film by 77% are next consideration consecutively according to the general people perception. The implication of the study is that the film makers and promoters should consider the factors properly for watching more films of the Dhallywood industry in relation to the foreign films especially Hindi, Tamil and English. The government can also take the initiative for the betterment of the industry through proper governance and subsidize if possible. -

Using 'North Wind and the Sun' Texts to Sample Phoneme Inventories

Blowing in the wind: Using ‘North Wind and the Sun’ texts to sample phoneme inventories Louise Baird ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University [email protected] Nicholas Evans ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University [email protected] Simon J. Greenhill ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University & Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History [email protected] Language documentation faces a persistent and pervasive problem: How much material is enough to represent a language fully? How much text would we need to sample the full phoneme inventory of a language? In the phonetic/phonemic domain, what proportion of the phoneme inventory can we expect to sample in a text of a given length? Answering these questions in a quantifiable way is tricky, but asking them is necessary. The cumulative col- lection of Illustrative Texts published in the Illustration series in this journal over more than four decades (mostly renditions of the ‘North Wind and the Sun’) gives us an ideal dataset for pursuing these questions. Here we investigate a tractable subset of the above questions, namely: What proportion of a language’s phoneme inventory do these texts enable us to recover, in the minimal sense of having at least one allophone of each phoneme? We find that, even with this low bar, only three languages (Modern Greek, Shipibo and the Treger dialect of Breton) attest all phonemes in these texts. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

A. Detailed Course Structure of MA (Linguistics)

A. Detailed Course Structure of M.A. (Linguistics) Semester I Course Course Title Status Module & Marks Credits Code LIN 101 Introduction to Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Linguistics LIN 102 Levels of Language Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Study LIN 103 Phonetics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 104 Basic Morphology & Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Basic Syntax LIN 105 Indo-European Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Linguistics & Schools of Linguistics Semester II LIN 201 Phonology Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 202 Introduction to Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Semantics & Pragmatics LIN 203 Historical Linguistics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 204 Indo-Aryan Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Linguistics LIN 205 Lexicography Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Semester III LIN 301 Sociolinguistics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 302 Psycholinguistics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 303 Old Indo-Aryan Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective Lin 304 Middle Indo-Aryan Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 305 Bengali Linguistics Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 1 Specific Elective LIN 306 Stylistics Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 307 Discourse Analysis Generic 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Elective Semester IV LIN 401 Advanced Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Morphology & Advanced Syntax LIN 402 Field Methods Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 403 New Indo-Aryan Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 404 Language & the Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Nation Specific Elective LIN 405 Language Teaching Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 406 Term Paper Discipline 50 6 Specific Elective LIN 407 Language Generic 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Classification & Elective Typology B. -

Tribes in India

SIXTH SEMESTER (HONS) PAPER: DSE3T/ UNIT-I TRIBES IN INDIA Brief History: The tribal population is found in almost all parts of the world. India is one of the two largest concentrations of tribal population. The tribal community constitutes an important part of Indian social structure. Tribes are earliest communities as they are the first settlers. The tribal are said to be the original inhabitants of this land. These groups are still in primitive stage and often referred to as Primitive or Adavasis, Aborigines or Girijans and so on. The tribal population in India, according to 2011 census is 8.6%. At present India has the second largest population in the world next to Africa. Our most of the tribal population is concentrated in the eastern (West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Jharkhand) and central (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattishgarh, Andhra Pradesh) tribal belt. Among the major tribes, the population of Bhil is about six million followed by the Gond (about 5 million), the Santal (about 4 million), and the Oraon (about 2 million). Tribals are called variously in different countries. For instance, in the United States of America, they are known as ‘Red Indians’, in Australia as ‘Aborigines’, in the European countries as ‘Gypsys’ , in the African and Asian countries as ‘Tribals’. The term ‘tribes’ in the Indian context today are referred as ‘Scheduled Tribes’. These communities are regarded as the earliest among the present inhabitants of India. And it is considered that they have survived here with their unchanging ways of life for centuries. Many of the tribals are still in a primitive stage and far from the impact of modern civilization. -

The Syllable Structure of Bangla in Optimality Theory and Its Application to the Analysis of Verbal Inflectional Paradigms in Distributed Morphology

The syllable structure of Bangla in Optimality Theory and its application to the analysis of verbal inflectional paradigms in Distributed Morphology von Somdev Kar Philosophische Dissertation angenommen von der Neuphilologischen Fakultät der Universität Tübingen am 09. Januar 2009 Tübingen 2009 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Neuphilologischen Fakultät der Universität Tübingen Hauptberichterstatter : Prof. Hubert Truckenbrodt, Ph.D. Mitberichterstatter : PD Dr. Ingo Hertrich Dekan : Prof. Dr. Joachim Knape ii To my parents... iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I owe a great debt of gratitude to Prof. Hubert Truckenbrodt who was extremely kind to agree to be my research adviser and to help me to formulate this work. His invaluable guidance, suggestions, feedbacks and above all his robust optimism steered me to come up with this study. Prof. Probal Dasgupta (ISI) and Prof. Gautam Sengupta (HCU) provided insightful comments that have given me a different perspective to various linguistic issues of Bangla. I thank them for their valuable time and kind help to me. I thank Prof. Sengupta, Dr. Niladri Sekhar Dash and CIIL, Mysore for their help, cooperation and support to access the Bangla corpus I used in this work. In this connection I thank Armin Buch (Tübingen) who worked on the extraction of data from the raw files of the corpus used in this study. And, I wish to thank Ronny Medda, who read a draft of this work with much patience and gave me valuable feedbacks. Many people have helped in different ways. I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratefulness to Prof. Josef Bayer for sending me some important literature, Prof. -

Proposal to Encode 0D5F MALAYALAM LETTER ARCHAIC II

Proposal to encode 0D5F MALAYALAM LETTER ARCHAIC II Shriramana Sharma, jamadagni-at-gmail-dot-com, India 2012-May-22 §1. Introduction In the Malayalam Unicode encoding, the independent letter form for the long vowel Ī is: ഈ where the length mark ◌ൗ is appended to the short vowel ഇ to parallel the symbols for U/UU i.e. ഉ/ഊ. However, Ī was originally written as: As these are entirely different representations of Ī, although their sound value may be the same, it is proposed to encode the archaic form as a separate character. §2. Background As the core Unicode encoding for the major Indic scripts is based on ISCII, and the ISCII code chart for Malayalam only contained the modern form for the independent Ī [1, p 24]: … thus it is this written form that came to be encoded as 0D08 MALAYALAM LETTER II. While this “new” written form is seen in print as early as 1936 CE [2]: … there is no doubt that the much earlier form was parallel to the modern Grantha , both of which are derived from the old Grantha Ī as seen below: 1 ma - īdṛgvidhā | tatarāya īṇ Old Grantha from the Iḷaiyānputtūr copper plates [3, p 13]. Also seen is the Vatteḻuttu Ī of the same time (line 2, 2nd char from right) which also exhibits the two dots. Of course, both are derived from old South Indian Brahmi Ī which again has the two dots. It is said [entire paragraph: Radhakrishna Warrier, personal communication] that it was the poet Vaḷḷattōḷ Nārāyaṇa Mēnōn (1878–1958) who introduced the new form of Ī ഈ. -

Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized

SFG2305 GPOBA for OBA Sanitation Microfinance Program in Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized Small Ethnic Communities and Vulnerable Peoples Development Framework (SECVPDF) May 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Executive Summary 3 B. Introduction 5 1. Background and context 5 2. The GPOBA Sanitation Microfinance Programme 6 C. Social Impact Assessment 7 1. Ethnic Minorities/Indigenous Peoples in Bangladesh 7 2. Purpose of the Small Ethnic Communities and Vulnerable Peoples Development Framework (SECVPDF) 11 D. Information Disclosure, Consultation and Participation 11 E. Beneficial measures/unintended consequences 11 F. Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) 12 G. Monitoring and reporting 12 H. Institutional arrangement 12 A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY With the Government of Bangladesh driving its National Sanitation Campaign from 2003-2012, Bangladesh has made significant progress in reducing open defecation, from 34 percent in 1990 to just once percent of the national population in 20151. Despite these achievements, much remains to be done if Bangladesh is to achieve universal improved2 sanitation coverage by 2030, in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Bangladesh’s current rate of improved sanitation is 61 percent, growing at only 1.1 percent annually. To achieve the SDGs, Bangladesh will need to provide almost 50 million rural people with access to improved sanitation, and ensure services are extended to Bangladesh’s rural poor. Many households in rural Bangladesh do not have sufficient cash on hand to upgrade sanitation systems, but can afford the cost if they are able to spread the cost over time. -

Why Dots and Dashes Matter: Writing Bengali in Roman Script Colonial Contexts, of Non-Roman Scripts Generally, Except for Greek

Carmen Brandt Why Dots and Dashes Matter Writing Bengali in Roman Script A friend recently sent me a photo of an Indian restaurant called “Vagina Tandoori” and asked for my ‘official statement’ as a scholar of South Asian studies. After we had had a good laugh – as many other Internet users had before us – I was not shy of providing an answer, as I explained the potential reason behind this awkward name: the restaurant owners could be of Bengali origin and might have transcribed the Bengali term ভািগনা/bhāginā1 “nephew”2, the way they thought it should be written in Roman script. I have come across this transcription several times in Bangladesh. Beyond that, a male colleague of mine regularly gets emails from his “vagina”, i.e. from a friend in Bangla- desh who is much younger to him and refers to himself as his “nephew”. Even though the awkward restaurant name turned out to be a hoax,3 the writing of South Asian lan- guages – especially Bengali – in Roman script is, nonetheless, often a challenge. Hence, this essay reflects on these challenges, discusses in general why South Asian languages are often written in Roman script, and which options might be best to do so. The Roman Script – a Symbol of Colonial Conquest As I have already discussed in detail (Brandt 2020), in South Asia, the Roman script is often perceived as a symbol of foreign domination in past and present. Its 1 All Bengali words are transliterated according to the rules in Table 4 below. 2 That means the son of one’s sister or the son of one’s husband’s sister.