The Thoughts of the Emperor M. Aurelius Antoninus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Alias Walter Lam Or Lam San Ping). A-5366278, Yokoya, Yoshi Or Sei Cho Or Shiqu Ono Or Yoshi Mori Or Toshi Toyoshima

B44 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—MAY 23, 1951 [65 STAT. A-3726892, Yau, Lam Chai or Walter Lum or Lum Chai You (alias Walter Lam or Lam San Ping). A-5366278, Yokoya, Yoshi or Sei Cho or Shiqu Ono or Yoshi Mori or Toshi Toyoshima. A-7203890, Young, Choy Shie or Choy Sie Young or Choy Yong. A-96:87179, Yuen, Wong or Wong Yun. A-1344004, Yunger, Anna Steibel or Anna Kirch (inaiden name). A-2383005, Zainudin, Yousuf or Esouf Jainodin or Eusoof Jainoo. A-5819992, Zamparo, Frank or Francesco Zamparo. A-5292396, Zanicos, Kyriakos. A-2795128, Zolas, Astghik formerly Boyadjian (nee Hatabian). A-7011519, Zolas, Edward. A-7011518, Zolas, Astghik Fimi. A-4043587, Zorrilla, Jesus Aparicio or Jesus Ziorilla or Zorrilla. A-7598245, Mora y Gonzales, Isidoro Felipe de. Agreed to May 23, 1951. May 23, 1951 [S. Con. Res. 10] DEPORTATION SUSPENSIONS Resolved hy the Senate (the House of Representatives concurrmgr), That the Congress favors the suspension of deportation in the case of each alien hereinafter named, in which case the Attorney General has suspended deportation for more than six months: A-2045097, Abalo, Gelestino or George Abalo or Celestine Aballe. A-5706398, Ackerman, 2Jelda (nee Schneider). A-4158878, Agaccio, Edmondo Giuseppe or Edmondo Joseph Agaccio or Joe Agaccio or Edmondo Ogaccio. A-5310181, Akiyama, Sumiyuki or Stanley Akiyama. A-7112346, Allen, Arthur Albert (alias Albert Allen). A-6719955, Almaz, Paul Salin. A-3311107, Alves, Jose Lino. A-4736061, Anagnostidis, Constantin Emanuel or Gustav or Con- stantin Emannel or Constantin Emanuel Efstratiadis or Lorenz Melerand or Milerand. A-744135, Angelaras, Dimetrios. -

Rhetorics of Stoic Philosophy in Eighteenth-Century Discourses of Sentiment

Out of Closets: Rhetorics of Stoic Philosophy in Eighteenth-Century Discourses of Sentiment Randall Cream The Spectator was one of those cultural icons whose importance was obvious even as it was being established. While it was not the first popular broadsheet to captivate its London readership, the Spectator proved to be a powerful voice in the rapid transformation of London culture in the early decades of the eighteenth century. In their publication of the Spectator, Joseph Addison and Richard Steele were able to substantially affect the eighteenth-century marketplace of ideas by regularizing the cultivation of morality as central to this milieu. Within the pages of the Spectator, morality emerges as a reciprocal relationship between virtuous individuals and a just civil society, forging a bridge between public good and private virtue while retaining the separate categories.1 As Alan McKenzie notes, the Spectator’s focus on social relations as a proper ethical sphere coincides with its function “of inculcating classical values and morals for a new, partly financial and mercantile public” (89).2 McKenzie’s work analyzes the complex relationship developed between the Spectator and its reader, a relationship that characterizes moral instruction, social connections, and self-understanding as “‘humanizing’ this new public” (89). But we can go further. One function of the Spectator’s specific combination of an ethics of interiority and a socialized network of moral relationships is the articulation of a subjectivity characterized by affective performance and self-restraint. This curious subjectivity, profoundly eighteenth-century in its split focus, is intricately linked to the discourses that compose the Spectator. -

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Originally translated by Meric Casaubon About this edition Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus was Emperor of Rome from 161 to his death, the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” He was nephew, son-in-law, and adoptive son of Antonius Pius. Marcus Aurelius was one of the most important Stoic philosophers, cited by H.P. Blavatsky amongst famous classic sages and writers such as Plato, Eu- ripides, Socrates, Aristophanes, Pindar, Plutarch, Isocrates, Diodorus, Cicero, and Epictetus.1 This edition was originally translated out of the Greek by Meric Casaubon in 1634 as “The Golden Book of Marcus Aurelius,” with an Introduction by W.H.D. Rouse. It was subsequently edited by Ernest Rhys. London: J.M. Dent & Co; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co, 1906; Everyman’s Library. 1 Cf. Blavatsky Collected Writings, (THE ORIGIN OF THE MYSTERIES) XIV p. 257 Marcus Aurelius' Meditations - tr. Casaubon v. 8.16, uploaded to www.philaletheians.co.uk, 14 July 2013 Page 1 of 128 LIVING THE LIFE SERIES MEDITATIONS OF MARCUS AURELIUS Chief English translations of Marcus Aurelius Meric Casaubon, 1634; Jeremy Collier, 1701; James Thomson, 1747; R. Graves, 1792; H. McCormac, 1844; George Long, 1862; G.H. Rendall, 1898; and J. Jackson, 1906. Renan’s “Marc-Aurèle” — in his “History of the Origins of Christianity,” which ap- peared in 1882 — is the most vital and original book to be had relating to the time of Marcus Aurelius. Pater’s “Marius the Epicurean” forms another outside commentary, which is of service in the imaginative attempt to create again the period.2 Contents Introduction 3 THE FIRST BOOK 12 THE SECOND BOOK 19 THE THIRD BOOK 23 THE FOURTH BOOK 29 THE FIFTH BOOK 38 THE SIXTH BOOK 47 THE SEVENTH BOOK 57 THE EIGHTH BOOK 67 THE NINTH BOOK 77 THE TENTH BOOK 86 THE ELEVENTH BOOK 96 THE TWELFTH BOOK 104 Appendix 110 Notes 122 Glossary 123 A parting thought 128 2 [Brought forward from p. -

Bullard Eva 2013 MA.Pdf

Marcomannia in the making. by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Eva Bullard 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Marcomannia in the making by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member During the last stages of the Marcommani Wars in the late second century A.D., Roman literary sources recorded that the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was planning to annex the Germanic territory of the Marcomannic and Quadic tribes. This work will propose that Marcus Aurelius was going to create a province called Marcomannia. The thesis will be supported by archaeological data originating from excavations in the Roman installation at Mušov, Moravia, Czech Republic. The investigation will examine the history of the non-Roman region beyond the northern Danubian frontier, the character of Roman occupation and creation of other Roman provinces on the Danube, and consult primary sources and modern research on the topic of Roman expansion and empire building during the principate. iv Table of Contents Supervisory Committee ..................................................................................................... -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abrev Nicknames

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abrev Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abby, Abbie, Ab, Gail, Nabby, Gubby, Deborah, Gobinet Gobnait Gobnata Gubbie, Debbie Abraham Ab, Abr, Ab, Abr, Abe, Abby Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abram Adam Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Aggie, Aggy, Assie, Inez, Nessa Nancy Aigneis Agnus, Agna, Agneta Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Lena Eileen Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Al, Bert, Albie, Bertie Ailbhe Albertus, Alberti Alexander Alexr Ala, Alec, Alex, Andi, Ec, Lex, Xandra, Ales Alistair, Alaster, Sandy Alastar, Saunder Alexander Alfred Al, Fred Ailfrid Alfredus Alice Eily, Alcy, Alicia, Allie, Elsie, Lisa, Ally, Alica Ellen Ailis, Eilish Alicia, Alecia, Alesia, Alitia Alicia Allie, Elsie, Lisa Alisha, Elisha Ailis, Ailise Alicia Allowshis Allow Aloysius, Aloyisius Aloysius Al, Ally, Lou Lewis Alaois Aloysius Ambrose Brose, Amy Anmchadh Ambrosius, Anmchadus, Animosus Amelia Amy, Emily, Mel, Millie Anastasia Anty, Ana, Stacy, Ant, Statia, Stais, Anstice, Anastatia, Anstace Annstas Anastasia Stasia, Ansty, Stacey Andrew And,Andw,Andrw Andy, Ansey, Drew Aindreas Andreas Ann/Anne Annie, Anna, Ana, Hannah, Hanna, Hana, Nancy, Nany, Nana, Nan, Nanny, Nainseadh, Neans Anna Hanah, Hanorah, Nannie, Susanna Nance, Nanno, Nano Anthony Ant Tony, Antony, Anton, Anto, Anty Anntoin, Antoin, Antoine Antonius, Antonious Archibald Archy, Archie Giolla Easpuig Arthur Artr, Arthr Art, Arty Artur Arcturus, Arturus Augustine Austin, Gus, Gustus, Gussy Augustus Aibhistin, Aguistin Augustinus, Augustinius Austin -

2013 7370 KELLY WINKLES ATTORNEY at LAW Deportationb(6), B(7)(C) Or Detained Information to Supply to the Coweta County State Court in Newnan, GA on and B(6), B(7)(C)

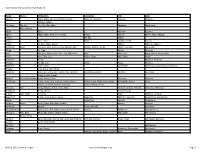

Recv'd in FOIA Case First Name Last Name Company Document Requested Number b(6), b(7)(c) 01/24/2013 7370 KELLY WINKLES ATTORNEY AT LAW deportationb(6), b(7)(c) or detained information to supply to the Coweta County State Court in Newnan, GA on and b(6), b(7)(c) 01/11/2013 7693 TARMO VAHTER EESTI AJALEHED AS all FBI documents about b(6), b(7)(c) 01/11/2013 7705 ANGELA BUSHNELL IMMIGRANTS FIRST, PLLC any and all documents relating to removal proceeding concerning b(6), b(7)(c) 01/10/2013 7710 NEIL SCHUSTER ATTORNEY AT LAW any and all central information for b(6), b(7)(c) 01/10/2013 7715 LSSI, ALLENWOOD a copy of the records belonging to b(6), b(7)(c) b(6), b(7)(c) b(6), b(7)(c) 01/10/2013 7908 copies of all information pertaining to b(6), b(7)(c) 01/10/2013 7909 MARK ZAID all records for maintained by the FBI b(6), b(7)(c) 01/10/2013 7912 KATHERINE MYRICK DEA HEADQUARTERS, any and all documents records located in the files of the US Drug ATTN; FOI/PA UNIT (SARF) Enforcement Administration related to b(6), b(7)(c) b(6), b(7)(c) coveringthe years 1969 to date b(6), b(7)(c) 01/10/2013 7916 REG. NO. any and all documents related to your extradixtion from the DR to HOUSING UNIT FCI U.S. b(6), b(7)(c) b(6), b(7)(c) b(6), b(7)(c) 01/08/2013 7930 FDC REG NO. -

Hamilton County (Ohio) Naturalization Records – Surname D

Hamilton County Naturalization Records – Surname D Applicant Age Country of Origin Departure Date Departure Port Arrive Date Entry Port Declaration Dec Date Vol Page Folder Naturalization Naturalization Date Restored Date Da Costa, Moses P. 37 England Liverpool New York T 04/03/1885 T F Daber, Nicholas 36 Bavaria Havre New Orleans T 12/26/1851 24 6 F F Dabinski, Casper 32 Prussia Bremen New York T 03/21/1856 26 40 F F Dabry, John Austria ? ? T 05/05/1890 T F Dacey, Daniel 21 Ireland London New York T 05/01/1854 8 319 F F Dacey, Daniel 21 Ireland London New York T 05/01/1854 9 193 F F DaCosta, Moses P. 37 England Liverpool New York T 04/03/1885 T F Dacy, Cornelius 25 Ireland Liverpool Boston T 07/29/1851 4 58 F F Dacy, Luke Ireland ? ? F T T 10/14/1892 Dacy, Timothy 25 Ireland Liverpool New Orleans T 07/29/1851 4 59 F F Daey, Jacob 26 Bavaria Antwerp New York T 08/04/1856 14 337 F F Dagenbach, Joseph A. 34 Germany Rotterdam New York T 03/19/1887 T F Dagenbach, Martin 22 Germany Rotterdam New York T 05/22/1882 T F Dahling, John 28 Mecklenburg Schwerin Hamburg New York T 10/06/1856 14 207 F F Dahlman, W. 25 Germany Antwerp New York T 12/08/1883 T F Dahlmann, David 37 Germany Havre New York T 10/14/1886 T F Dahlmans, Christian Germany Antwerp New York T 04/11/1887 T F Dahman, Peter Joseph 52 Prussia Liverpool New York T 12/??/1849 23 22 F F Dahmann, Henry 46 Hanover Bremen New Orleans T 10/01/1856 14 134 F F Dahms, Otto 35 Germany Rotterdam New York T 12/15/1893 T F Dahringer, Joseph 33 Germany Havre New York T 05/17/1884 T F Daigger, Anton Germany ? ? T 03/18/1878 T F Dailey, Con 16 Ireland ? New York F T T 10/20/1887 Dailey, Eugene 25 Ireland Queenstown Baltimore T 08/03/1886 T F Daily, ? ? ? ? T 10/28/1850 2 320 F F Daily, Carrell 34 Ireland Liverpool New York T 01/06/1860 27 32 F F Daily, Martin 50 Ireland Liverpool Buffalo T 09/27/1856 14 406 F F Dake, John 23 France Havre New Orleans T 03/11/1853 7 324 F F Dakin, Francis 26 Ireland Liverpool New Orleans T 12/27/1852 5 448 F F Dalberg, Albert M. -

What Is the Relationship Between Dietary Patterns Consumed and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes?: Systematic Review Protocol

DRAFT – Current as of 4/20/2020 WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DIETARY PATTERNS CONSUMED AND RISK OF TYPE 2 DIABETES?: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROTOCOL This document describes the protocol for a systematic review to answer the following question: What is the relationship between dietary patterns consumed and risk of type 2 diabetes? The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, Dietary Patterns Subcommittee, answered this question using by conducting a systematic review with support from USDA’s Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR), part of which involved updating an existing NESR systematic review. NESR methodology for answering a systematic review question involves: • searching for and selecting articles, • extracting data and assessing the risk of bias of results from each included article, • synthesizing the evidence, • developing a conclusion statement, • grading the evidence underlying the conclusion statement, and • recommending future research. More information about NESR’s systematic review methodology, used in this systematic review update, is available on the NESR website: https://nesr.usda.gov/2020-dietary-guidelines-advisory- committee-systematic-reviews. The existing NESR systematic review updated as part of this work was conducted for the 2014 Dietary Patterns Systematic Review Project by a Technical Expert Collaborative and staff from USDA’s NESR. Complete documentation of the systematic review is available on NESR’s website: • https://nesr.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2019-04/DietaryPatternsReport-FullFinal.pdf • Methodology from the 2014 Dietary Patterns Systematic Review Project: https://nesr.usda.gov/dietary-patterns-systematic-review-project-methodology This protocol is up-to-date as of: 4/20/2020. This document reflects the protocol as it was implemented. -

In Defense of Stoicism

In Defense of Stoicism by ALEX HENDERSON* Georgetown University Abstract This article employs Cicero’s assault on Stoic philosophy inPro Murena as a point of departure to engage three critical aspects of Stoicism: indifference to worldly concerns, the sage as an ideal, and Stoic epistemology. It argues that Cicero’s analysis fails to clearly distinguish between these elements of Stoic philosophy and, therefore, presents Stoicism in a misleadingly unfavorable light. harges of bribery were brought against Lucius Licinius Murena in 62 bce. Despite entrenched opposition from the popular Cparty, Murena was able to enlist the aid of the famed orator and presiding consul Marcus Tullius Cicero. His prosecutor was the most conservative of senators—Marcus Porcius Cato, famed for his rectitude and his unbending adherence to Stoic philosophy. In order to defend Murena, who was almost certainly guilty, Cicero chose to go on the offensive and discredit his opponent by undermining Stoic philosophy in the eyes of the jury. Cicero portrays Stoicism as follows: A wise person never allows himself to be influenced… Philosophers are people who, however ugly, remain handsome; even if they are very poor, they are rich; even if they are slaves, they are kings. All sins are equal, so that every misdemeanor is a serious crime… The philosopher has no need to offer conjectures, never regrets what he has done, is never mistaken, never changes his mind.1 Cicero’s portrayal seems to argue that (1) the Stoics’ commitment to remain indifferent to worldly influence causes them to lack compassion for the circumstances of other people, (2) Stoics are too severe when * [email protected]. -

PROPAEDEUTICS: the FORMATION of a LA TIN SOPHIST Time And

CHAPTER ONE PROPAEDEUTICS: THE FORMATION OF A LA TIN SOPHIST Time and Place The extant version of Apuleius' account of his defence of himself against charges of practising magic provides the chronological framework for arranging many of the known events of his life. The trial was conducted before Claudius Maximus, the proconsul of Africa, in the coastal town of Sabrata, some sixty kilometres from Oea (modern Tripoli in Libya), where the events for which he was tried were alleged to have occurred. There is now general agreement that Maximus held the proconsulship of Africa during the one-year period 158/159; thus Apuleius' trial took place at that time as Maximus was conducting the assizes there. 1 The only other datable events recorded in Apuleius' writings are consistent with this date. In the Apology (85.2), he reproaches one of the plaintiffs for arranging to have read into the court record a distorted version of one of his wife's letters in the presence of the statues of the reigning emperor Antoninus Pius ( 138-161). 2 Florida 9, part of a speech presented by Apuleius in Carthage, bids farewell to Severianus at the end of his proconsulate of Africa in 164. 3 This is in fact the latest attested date for the life of Apuleius. 4 Other, less precise dates can be gleaned by a process of inference from, and reference to, the fixed dates. Apuleius states that at the time 1 Syme 1959: 316-7; for slightly different interpretations and additional details see Carratello 1963: 97-110 and Guey 1951 : 307-17. -

Index Hominum

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89724-2 - The Religion of Senators in the Roman Empire: Power and the Beyond Zsuzsanna Varhelyi Index More information Index hominum (Entries marked with an asterisk are debated identifications) 2 2 Aburnius Caedicianus, Q. (PIR A21), 142 Annaeus Lucanus, M. (PIR A611), 156 2 2 Acilius Attianus, P. (PIR A45), 31 Annaeus Placidus, T. (PIR A614), 97, 199 2 2 Acilius Aviola (PIR A48), 224 Annaeus Seneca, L. (PIR A617), 53, 57, 58, 59, Acilius Glabrio Cn. Cornelius Severus, M’. 63, 79, 80, 81, 87, 88, 158, 163, 164, 165, 171, 2 (PIR A73), 221 172, 173, 177, 180 2 Acilius Priscus A. Egrilius Plarianus, M. Annia Regilla (PIR A720), 43 2 2 (*PIR E48), 119, 224 Annius Arminius Donatus, C. (PIR 2 Acilius Severus (PIR A80), 224 A634), 217 2 2 Acilius Vibius Faustinus, M’.(PIR A86), 221 Annius Camars (PIR A638), 219 2 2 Aedius Celer, M. (PIR C626), 224 Annius Italicus Honoratus, L. (PIR A659), 144 2 2 Aelius Antipater (PIR A137), 217 Annius Largus, L. (PIR A662), 110 2 2 Aelius Coeranus Iun(ior), P. (PIR A162), 115 Annius Largus, L. (PIR A664), 221 2 2 Aemilius Arcanus, L. (PIR A333), 218 Annius Longus, L. (PIR A669), 219 2 Aemilius Carus, L. (PIR online, CIL III 1153), Annius Ravus, L. (PIR A684), 60, 221 142, 145 Anteius Orestes, P. (PIR online, RE Suppl. 2 Aemilius Carus, L. (PIR A338), 136, 137 14 [1974] 50 s.v. Antius 11a), 128 2 Aemilius Flaccus, M. (PIR A343), 118 Antistius Adventus Postumius Aquilinus, Q. -

Ashmolean Monumental Latin Inscriptions

30-Apr-19 Ashmolean Monumental Latin Inscriptions Acknowledgements Marta Adsarias (Universiteit van Amsterdam, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Bibliotheek Bijzondere Collecties); Benjamin Altshuler (CSAD); Abigail Baker (ASHLI); Alex Croom (Arbeia Museum); Hannah Cornwell (ASHLI); Charles Crowther (CSAD); Judith Curthoys (Christ Church, Oxford); Harriet Fisher (Corpus Christi College, Oxford); Suzanne Frey- Kupper (Warwick); Jenny Hall (Museum of London); Helen Hovey (Ashmolean Museum); Jane Masséglia (ASHLI); Lorenzo Miletti (University of Naples "Federico II"); Alessandro Moro (Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice); Ilaria Perzia (Ashmolean Museum); Stefania Peterlini (BSR); Angela Pinto (Biblioteca Nazionale "Vittorio Emanuele III" - Laboratorio fotografico digitale); Philomen Probert (Oxford); Jörg Prüfert (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz: Dept. of Conservation and Digitization); Nicholas Purcell (Brasenose College, Oxford); Paul Roberts (Ashmolean Museum); Maggy Sasanow (CSAD); Valerie Scott (BSR); Margareta Steinby (Helsinki/ Oxford); Will Stenhouse (Yeshiva University); Bryan Sitch (Manchester Museum); Conor Trainor (Warwick); Michael Vickers (Ashmolean Museum); Susan Walker (Ashmolean Museum); John Wilkes (Oxford) 1 30-Apr-19 Epigraphic conventions Abbreviations: a(bc) = An abbreviated word, which the editor has written out in full. a(---) = An abbreviated word, which cannot be completed. a(bc-) = An abbreviated word, which the editor has written out in full, but only the stem of the word is evident. Damage suffered