Interview with Leonard Beetstra # AI-A-L-2008-034 Interview # 1: December 4, 2007 Interviewer: Phil Pogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beck 1-1000 Numbered Checklist 1962-1975

Free checklist, download at http://www.beck.ormurray.com/ Beck Number QTY W=Winick B "SPACE" Ship/Location Hull Number Location Cachet/ Event Cancel Date MT, Comment BL=Beck Log, If just a "LOW" number, it means that both Hand agree. "CREW" 1-Prototype No record of USS Richard E Byrd DDG-23 Seattle, WA Launching FEB 6/?130PM/1962 MT No Beck number. count 1-Prototype No record of USS Buchanan DDG-14 Commission FEB/7/1962/A.M. HB No Beck number. count 1-Prototype No record of USS James Madison SSBN-627 Newport News, Keel Laying MAR 5/930 AM/1962 MT No Beck number count VA Prototype No record of USS John C Calhoun SSBN-630 Newport News, Keel Laying MT No Beck number count VA JUN 4/230PM/1962 Prototype No record of USS Tattnall DDG-19 Westwego, LA Launching FEB 13/9 AM/1962 HT count 1-"S" No record of USS Enterprise CVAN-65 Independence JUL/4/8 AM/1962 HB count Day 1 43 USS Thomas Jefferson SSBN-618 Newport News, Launching FEB/24/12:30PM/1962 MT VA 2 52 USS England DLG-22 San Pedro, CA Launching MAR 6/9AM/1962 MT 3 72 USS Sam Houston SSBN-609 Newport News, Commission MAR 6/2PM/1962 MT VA 3 USS Sam Houston SSBN-609 Newport News, Commission MR 06 2 PM/1962 HT eBay VA 4 108 USS Thomas A Edison SSBN-610 Groton, CT Commission MAR 10/5:30PM/1962 MT 5 84 USS Pollack SSN-603 Camden, NJ Launching MAR17/11-AM/1962 MT 6 230 USS Dace SSN-607 Pascagoula, Launching AUG 18/1962/12M MT MS 6 Cachet Variety. -

The Alliance of Military Reunions

The Alliance of Military Reunions Louis "Skip" Sander, Executive Director [email protected] – www.amr1.org – (412) 367-1376 153 Mayer Drive, Pittsburgh PA 15237 Directory of Military Reunions How to Use This List... Members are listed alphabetically within their service branch. To jump to a service branch, just click its name below. To visit a group's web site, just click its name. Groups with names in gray do not currently have a public web site. If you want to contact one of the latter, just send us an email. To learn more about a member's ship or unit, click the • to the left of its name. Air Force Army Coast Guard Marine Corps Navy Other AIR FORCE, including WWII USAAF ● 1st Computation Tech Squadron ● 3rd Air Rescue Squadron, Det. 1, Korea 1951-52 ● 6th Weather Squadron (Mobile) ● 7th Fighter Command Association WWII ● 8th Air Force Historical Society ● 9th Physiological Support Squadron ● 10th Security Police Association ● 11th Bombardment Group Association (H) ● 11th & 12th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadrons Joint Reunion ● 13 Jungle Air Force Veterans Association ● 15th Radio Squadron Mobile (RSM) USAFSS ● 20th Fighter Wing Association ● 34th Bomb Squadron ● 34th Tactical Fighter Squadron, Korat Thailand ● 39th Fighter Squadron Association ● 47th Bomb Wing Association ● 48th Communications Squadron Association ● 51st Munitions Maintenance Squadron Association ● 55th & 58th Weather Reconnaissance Squadrons ● 57th TCS/MAS/AS/WPS (Troop Carrier Squadron, Military Airlift Squadron, Airlift Squadron, Weapons Squadron) Military -

Americanlegionvo1371amer.Pdf (7.501Mb)

Haband comforl joe slacks matching shirts $15.95ea. 100 Fairview Ave., WHAT WHAT HOW WHAT HOW 7TE-03V waIst? INSEAM? MANY? 7TE-16R MANY? Prospect Park, NJ 07530 B Khaki F Aqua Please send me C Royal A Ligint Blue pairs of slacks. I enclose D Teal E Teal purchase price G Grey B Wtiite plus $3.95 toward postage M Navy C Grey and liandling. Check Enclosed Exp.: LIFETIME GUARANTEE: 100% Satisfaction Guaranteed or _Apt.#_ Full Refund of Purchase Price At Any Time! -Zip. I Full S-t-r-e-t-c-li Waist Wear them with a belt or without; either way, you'll love the comfort! \ khaki Crisp, cool fabric is from famous Wamsutta Springs Mills. The polyester and cotton blend is just right for machine wash and dry easy care! Plus you get: • Full elastic waist & belt loops • Front zipper & button closure • NO-IRON wash & wear • 2 slash front pockets • 2 back patch pockets • Full cut made in U.S.A. •5 FAVORITE COLORS: Choose from Khaki, Grey, Royal, Navy, & Teal. WAISTS: 30-32-34-35-36-37- 38-39-40-41-42-43-44 *BIG MEN'S: Add»2.50 per pair for 46-48-50-52-54 INSEAMS: S(27-28], M(29-30) L(31-32), XL(33-34) Matching shirt 15*£4ch Handsome color-matclied yarn-dyed trim accents chest and shoulder.l-landy chest pocket. Cotton/polyester knit. Wash & wear care. Imported. Sizes: S(14-14'4), M(15-15'/2), L{16-16'/j),XL{17-17y2), 'Add ^2.50 per shirt for: 2XL(18-18'/2),and aXMig-IO'/^) ^^^^J lOO Fairview Ave., Prospect ParK,NJ 07530 26 The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. -

USS PRICHETT LOOK out Jan 2011

JANUARY 2011 Volume IV Issue III USS PRICHETT DD-561 REUNION ASSOCIATION LOOK OUT Prez Says WE ARE ON THE WEB www.ussprichettdd561. Hello Shipmates and Friends, I hope this finds everyone healthy, happy and warm. We have the happy part down, Mary Ann blew the healthy part (flu) and it definitely is not warm here. Another year is underway. This year we are going to push everyone to recruit missing shipmates. We know they are out there and some of you may have leads to find them. We have too many shipmates in our directory that have not shown any interest in the Association or attending the reunions. We need to put a hand out to them and bring them back on board. At the present it looks like the officer’s board meeting will be the last weekend of February and probably in Tunica, Mississippi. I believe most of the board plans on arriving on Friday night but we may not be able to make it until Saturday. If you are in the area stop by and say hello. The hotel has not been picked yet so give me a shout when it gets closer and I will have the details. This year we are planning on setting up our ship store on our web site. You will be able to view what we have and then give us a call and we will get it out to you. There are a lot of sweatshirts in the store that feel pretty good right now along with some jackets. -

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents Background This ships list is intended to provide VA regional offices with a resource for determining whether a particular US Navy or Coast Guard Veteran of the Vietnam era is eligible for the presumption of Agent Orange herbicide exposure based on operations of the Veteran’s ship. According to 38 CFR § 3.307(a)(6)(iii), eligibility for the presumption of Agent Orange exposure requires that a Veteran’s military service involved “duty or visitation in the Republic of Vietnam” between January 9, 1962 and May 7, 1975. This includes service within the country of Vietnam itself or aboard a ship that operated on the inland waterways of Vietnam. However, this does not include service aboard a large ocean- going ship that operated only on the offshore waters of Vietnam, unless evidence shows that a Veteran went ashore. Inland waterways include rivers, canals, estuaries, and deltas. They do not include open deep-water bays and harbors such as those at Da Nang Harbor, Qui Nhon Bay Harbor, Nha Trang Harbor, Cam Ranh Bay Harbor, Vung Tau Harbor, or Ganh Rai Bay. These are considered to be part of the offshore waters of Vietnam because of their deep-water anchorage capabilities and open access to the South China Sea. In order to promote consistent application of the term “inland waterways”, VA has determined that Ganh Rai Bay and Qui Nhon Bay Harbor are no longer considered to be inland waterways, but rather are considered open water bays. -

Hydraulics Laboratory Stratified Flow Channel Pumps History

Hydraulics Laboratory Stratified Flow Channel Pumps History Douglas Alden Senior Development Engineer Hydraulics Laboratory Technology Application Group Integrative Oceanography Division Scripps Institution of Oceanography UC San Diego 4 Apr 2014 The Hydraulics Laboratory Stratified Flow Channel (SFC) was developed to enhance the understanding of fluid mechanics crucial to many ocean processes and studies. It was dedicated 4 Jun 1982. HLab lore had it that the two pumps used for the channel were surplus US Navy inventory out of a WWII Destroyer. Recent research has determined that the pumps did come from a US Navy Fletcher-class Destroyer. A letter from Mr. Charles E. Pybas from Warren Pump Houdaille, Warren MA to John Powell dated 5 June 1980 included documentation on the pumps which were part of an order of 25” Main Condenser Circulating Pumps delivered to the US Navy during the height of WWII. The pumps were delivered to the US Navy for DD-554 – hull 11 to DD-568 – hull 25 over the time period from 1 Oct 1942 to 1 Aug 1943. John Powell inspecting the SFC (undated). Fletcher-class Destroyers1 DD-554 USS Franks Sold for scrap 1 Aug 1973 DD-555 USS Haggard Broken up for scrap at Norfolk Navy Yard 6 Mar 1946 DD-556 USS Hailey Sunk as a target 1982 by Brazil DD-557 USS Johnston Sunk by Japanese warships off Samar 25 Oct 1944 DD-558 USS Laws Sold for scrap 3 Dec 1973 DD-559 USS Longshaw Grounded off Okinawa and sunk by Japanese shore batteries 18 May 1945 DD-560 USS Morrison Sunk by Japanese Kamikaze aircraft off Okinawa 4 May 1945 DD-561 -

Uss Gearing Dd - 710

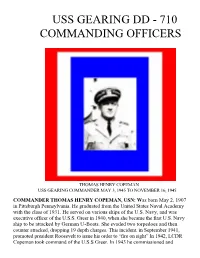

USS GEARING DD - 710 COMMANDING OFFICERS THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN USS GEARING COMMANDER MAY 3, 1945 TO NOVEMBER 16, 1945 COMMANDER THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN, USN: Was born May 2, 1907 in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy with the class of 1931. He served on various ships of the U.S. Navy, and was executive officer of the U.S.S. Greer in 1940, when she became the first U.S. Navy ship to be attacked by German U-Boats. She evaded two torpedoes and then counter attacked, dropping 19 depth charges. This incident, in September 1941, promoted president Roosevelt to issue his order to “fire on sight” In 1942, LCDR Copeman took command of the U.S.S Greer. In 1943 he commissioned and commanded the new Destroyer U.S.S. Brown, and on M ay 3, 1945 he commissioned and commanded the first of a new class of long hull Destroyer, the U.S.S. Gearing DD-710. Commander Copeman commanded the attack cargo ship U.S.S. Ogelethorpe in the Korean Theater of operations. From 1955 to 1956 he was chief staff officer, service force, sixth fleet, his final active duty was that of deputy t chief of staff of the 11 Naval district, He retired in July 1960 as Captain and made his home in Del Mar, California. His decorations included the Silver Star with combat V and the commendation medal with V and Star. Captain Copeman died on December 21, 1982 while hospitalized in San Diego, California. OBITUARY: The San Diego Union Tribune, Sunday 23, 1982 - Capt. -

Uss Gearing Dd - 710 Commanding Officers

USS GEARING DD - 710 COMMANDING OFFICERS THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN USS GEARING COMMANDER MAY 3, 1945 TO NOVEMBER 16, 1945 COMMANDER THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN, USN: Was born May 2, 1907 in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy with the class of 1931. He served on various ships of the U.S. Navy, and was executive officer of the U.S.S. Greer in 1940, when she became the first U.S. Navy ship to be attacked by German U-Boats. She evaded two torpedoes and then counter attacked, dropping 19 depth charges. This incident, in September 1941, promoted president Roosevelt to issue his order to “fire on sight” In 1942, LCDR Copeman took command of the U.S.S Greer. In 1943 he commissioned and commanded the new Destroyer U.S.S. Brown, and on May 3, 1945 he commissioned and commanded the first of a new class of long hull Destroyer, the U.S.S. Gearing DD-710. Commander Copeman commanded the attack cargo ship U.S.S. Ogelethorpe in the Korean Theater of operations. From 1955 to 1956 he was chief staff officer, service force, sixth fleet, his final active duty was that of deputy chief of staff of the 11th Naval district, He retired in July 1960 as Captain and made his home in Del Mar, California. His decorations included the Silver Star with combat V and the commendation medal with V and Star. Captain Copeman died on December 21, 1982 while hospitalized in San Diego, California. OBITUARY: TheSanDiegoUnionTribune, Sunday 23, 1982 - Capt. T. -

US Invasion Fleet, Guam, 12 July

US Invasion Fleet Guam 12 July - August 1944 Battleships USS Alabama (BB-60) USS California (BB-44) USS Colorado (BB-45) USS Idaho (BB-42) USS Indiana (BB-58) USS Iowa (BB-61) USS New Jersey (BB-62) USS New Mexico (BB-40) USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) USS Tennessee (BB-43) USS Washington (BB-56) Carriers: USS Anzio (CVE-57) USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24) USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) USS Cabot (CVL-28) USS Chenango (CVE-28) USS Corregidor (CVE-58) USS Essex (CV-9) USS Franklin (CV-13) USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) USS Hornet (CV-12) USS Kalinin Bay (CVE-68) USS Kitkun Bay (CVE-71) USS Kwajalein (CVE-98) USS Langley (CVL-27) USS Lexington (CV-16) USS Midway (CVE-63) USS Monteray (CVL-36) USS Nehenta Bay (CVE-74) USS Princeton (CVL-23) USS Sangamon (CVE-26) USS San Jacinto (CVL-30) USS Santee (CVE-29) USS Wasp (CV-18) USS Yorktown (CV-10) Cruisers: USS Biloxi (CL-80) USS Birmingham (CL-62) USS Boston (CA-6) USS Canberra (CA-70) USS Cleveland (CL-55) USS Denver (CL-58) USS Honolulu (CL-18) USS Houston (CL-81) USS Indianapolis (CA-35) USS Louisville (CA-28) USS Miami (CL-89) USS Minneapolis (CA-36) 1 USS Mobile (CL-63) USS Montpelier (CL-57) USS New Orleans (CA-32) USS Oakland (CL-95) USS Reno (CL-96) USS St. Louis (CL-49) USS San Diego (CL-53) USS San Francisco (CA-38) USS San Juan (CL-54) USS Santa Fe (CL-60) USS Vincennes (CL-64) USS Wichita (CA-15) Destroyers USS Abbot (DD-629) USS Acree (DE-167) USS Anthony (DD-515) USS Auliek (DD-569) USS Charles F. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

1. 376'6" B. 39'8", Dr. 17'9", S. 37 K.Cpl. 319; A. 5 5", 10 40Mm., 7 20Mm., 10 21" Tt., 6 Dcp., 2 Dct., Cl

(DD-561: dp. 2,940 tf.) ,1. 376'6" b. 39'8", dr. 17'9", s. 37 k.cpl. 319; a. 5 5", 10 40mm., 7 20mm., 10 21" tt., 6 dcp., 2 dct., cl. Fletcher) Prichett (DD-561) was laid down 20 July 1942 by the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Co., Seattle, Wash., Iaunched 31 July 1943, sponsored by Mrs. Orville A. Tucker, and commissioned 15 January 1944, Comdr. Cecil T. Caulfield in command. Following shakedown Prichett sailed 1 April 1944, for Majuro, thence to Manus where she joined the battleships of TF 58. On the 28th, TG 58.3 sortied and, rendezvousing with the fast carriers, steamed northeast. On the 29th and 30th they blasted Truk and, on 1 May, pounded Ponape. Then the force retired to Majuro, whence Prichett returned to Pearl Harbor. There fighter director equipment was installed and on 30 May she sailed west again, with TF 52 for the invasion of Saipan. Having screened the transports to the objective, she shifted her protective duties to the battleships as they bombarded the shore, then provided gunfire support to the troops landed on 15 June. During the Battle of the Philippine Sea she remained with the transports, then turned her guns on the neighboring Japanese held island of Tinian. Remaining in the Marianas until mid-August, she alternated gunfire support duties, screening duties and radar picket duties off Saipan with bombardment of Tinian until that island was invaded 24 July, then provided support services for the troops fighting there. In August she shifted to Guam to support mopping up operations and on the 17th got underway for Eniwetok to rejoin the fast carrier force, now designated TF 38. -

![The American Legion [Volume 134, No. 2 (February 1993)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3627/the-american-legion-volume-134-no-2-february-1993-4223627.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 134, No. 2 (February 1993)]

2 for $39.50 3 for $59. Haband Company 100 Fairview Ave., Regular Sizes: S(34-36) M(38-40) Prospect Park, NJ L(42-44) XL{46-48) 07530 "Big Men's Sizes: Add $4 for sizes: Send me 2XL(50-52) 3XL(54-56) WHAT HOW 7TY-3E7 SIZE? MANY? jackets. I enclose $ purchase A Tan-Multi price plus $2.95 B Grey-Multi toward postage C Blue-Multi and handling. D Stone-Plum Check Enclosed or SEND NO MONEY NOW if you use your: Exp.: / Name Street City _ .Zip. 100% SATISFACTION GUARANTEED or FULL REFUND of purchase price at any time! NOW UNDER *20! Thafs Right! Under $20 for a jacket you'll wear a full three seasons of the year! Under $20 for this handsome, broad- shouldered designer look. And under $20 for a jacket loaded with all these quality features! HURRYAM) SAVE! tan - \ multi Stay Warm! Stay Dry! Look Great! Feel Proud! • Tight-woven polyester and cotton poplin shell. • Water-repellent protection. • Fully nylon lined. • 3 big pockets (one hidden inside for security). • Soft, baseball style knit collar with contrast trim. • Adjustable snap cuffs. • Elasticized side hem. • Generous full cut and no-bind comfort fit. • An exclusive Haband quality import Use the coupon above and send today while this New Customer Special lasts! 7 The Magazine for a Strong America Vol.134, No. 2 February 1 993 VIETNAM TWENTY-FIVE YEARS LATER The countryside hasforgotten what man cannot. Photos by Geoffrey Clifford 1 TET TWENTY-FIVE YEARS LATER From thejungle to the Pentagon, five writers look back at the Tet Offensive.