{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 86 International Conference on Economics and Management, Education, Humanities and Social Sciences (EMEHSS 2017) Research on the Development Countermeasures of Qingjiang Gallery based on the Life Cycle Theory Xiaohui Shaoa, *, Chun Liub School of Management, Wuhan Industry and Business University, Wuhan 430065, China [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Qingjiang Gallery is located in Changyang County of Hubei province, which is a national geological park in Hubei province, became the national AAAAA level scenic area in 2012 officially. In order to achieve the sustainable development, how to enhance the core competitiveness and how to attract more tourists are the main problems that Qingjiang Gallery should focus on. This paper tries to do a questionnaire survey, based on the Life Cycle Theory to analyze the status quo of Qingjiang Gallery scenic area, then try to propose some development countermeasures. Keywords: Qingjiang Gallery, scenic area, life cycle, countermeasures. 1. Introduction of the Research Based on life cycle of tourism scenic spot research is based on life cycle theory to analyze the practical situation of tourism destinations. Through the case study Gray·R·Hovinen (1982) pointed out that the tourism development of Lancaster county has experienced five stages , thanks to its superior location and diversity of tourism resources the tourism destination has strong vitality, visitors won't have too big reduce in the long run [2]. Sheela Agarwal -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

An Improved Evaluation Scheme for Performing Quality Assessments of Unconsolidated Cultivated Land

sustainability Article An Improved Evaluation Scheme for Performing Quality Assessments of Unconsolidated Cultivated Land Lina Peng 1,2, Yan Hu 2,3, Jiyun Li 4 and Qingyun Du 1,5,6,* 1 School of Resource and Environmental Science, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] 2 Wuhan Hongfang Real Estate & Land Appraisal. Co, Ltd., Room 508, District, International Headquarters, Han Street, Wuchang District, Wuhan 430061, China; [email protected] 3 School of Logistics and Engineering Management, Hubei University of Economics, 8 Yangqiao Lake Road, Canglongdao Development Zone, Jiangxia District, Wuhan 430205, China 4 School of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Central China Normal University, 152 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] 5 Key Laboratory of GIS, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China 6 Key Laboratory of Digital Mapping and Land Information Application Engineering, National Administration of Surveying, Mapping and Geo-information, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079,China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-6877-8842; Fax: +86-27-6877-8893 Received: 5 June 2017; Accepted: 21 July 2017; Published: 27 July 2017 Abstract: Socioeconomic factors are extrinsic factors that drive spatial variability. They play an important role in land resource systems and sometimes are more important than that of the natural setting. The study aims to build a comprehensive framework for assessing unconsolidated cultivated land (UCL) in the south-central and southwestern portions of Hubei Province, China, which have not experienced project management and land consolidation, to identify the roles of natural and especially socioeconomic factors. -

Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in Figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011

37 Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 FAO WATER Irrigation in Southern REPORTS and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 37 Edited by Karen FRENKEN FAO Land and Water Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2012 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107282-0 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

Poll Results of Agm and Class

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (1) POLL RESULTS OF AGM AND CLASS MEETINGS HELD ON 20 MAY 2020; (2) PAYMENT OF FINAL DIVIDEND; (3) APPOINTMENT OF DIRECTORS AND SUPERVISORS; AND (4) AMENDMENTS TO THE ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION References are made to the notice of the 2019 annual general meeting, the notice of the first H shareholders class meeting of 2020 dated 3 April 2020 and the circular of the 2019 annual general meeting and the first H shareholders class meeting of 2020 dated 29 April 2020 (the “Circular”) of Bank of Guizhou Co., Ltd.* (the “Bank”). Unless otherwise defined herein, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the Circular. I. POLL RESULTS OF THE AGM AND THE CLASS MEETINGS The AGM and the Class Meetings were held at 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday, 20 May 2020 at the Guizhou Hall, First floor, International Conference Center of Guizhou Province (No.66, Beijing Road, Yunyan District, Guiyang City, Guizhou Province, the PRC). The convening and holding of the AGM and the Class Meetings were in compliance with the requirements of the applicable laws and regulations of the PRC, the Listing Rules and the Articles of Association. – 1 – The AGM As at the date of the AGM, the total number of issued ordinary Shares of the Bank was 14,588,046,744, including 12,388,046,744 Domestic Shares and 2,200,000,000 H Shares, representing the total number of the Shares entitled the Shareholders to attend the AGM. -

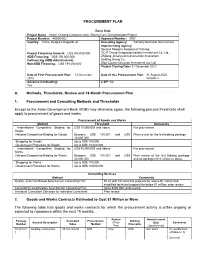

PROCUREMENT PLAN A. Methods, Thresholds, Review and 18-Month

PROCUREMENT PLAN Basic Data Project Name: Hubei Yichang Comprehensive Elderly Care Demonstration Project Project Number: 49309-002 Approval Number: 3767 Country: China, People's Republic of Executing Agency: Yichang Municipal Government Implementing Agency: Second People's Hospital of Yichang, Project Financing Amount: US$ 305,050,000 YCJT Group Kangyang Industry Investment Co. Ltd, ADB Financing: US$ 150,000,000 Zhijiang Jinrunyuan Construction Investment Cofinancing (ADB Administered): Holding,Group Co., Non-ADB Financing: US$ 155,050,000 Zigui County Chuyuan Investment Co. Ltd. Project Closing Date: 31 December 2024 Date of First Procurement Plan: 13 December Date of this Procurement Plan: 31 August 2020, 2018 Version 4 Advance Contracting: e-GP: No Yes A. Methods, Thresholds, Review and 18-Month Procurement Plan 1. Procurement and Consulting Methods and Thresholds Except as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) may otherwise agree, the following process thresholds shall apply to procurement of goods and works. Procurement of Goods and Works Method Threshold Comments International Competitive Bidding for US$ 10,000,001 and Above For prior review Goods National Competitive Bidding for Goods Between US$ 100,001 and US$ Prior review for the first bidding package 10,000,000 Shopping for Goods Up to US$ 100,000 Government Procedure for Goods Up to US$ 10,000,000 International Competitive Bidding for US$ 40,000,001 and Above For prior review Works National Competitive Bidding for Works Between US$ 100,001 and US$ Prior review of the first bidding package 40,000,000 and all packages $10 million or above Shopping for Works Up to US$ 100,000 Government Procedure for Works Up to US$ 10,000,000 Consulting Services Method Comments Quality- and Cost-Based Selection for Consulting Firm 80:20 with full technical proposal for above $1 million and simplified technical proposal for below $1 million, prior review Consultant's Qualification Selection for Consulting Firm Up to $200,000, prior review Individual Consultant Selection for Individual Consultant Prior review 2. -

For Personal Use Only 603 Page 1/3 15 July 2001

For personal use only 603 page 1/3 15 July 2001 Form 603 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671B Notice of initial substantial holder To Company Name/Scheme Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd ACN/ARSN 100686226 1. Details of substantial holder (1) Name HNA Tourism Group Co., Ltd (海航旅业集团有限公司) and each of the other entities set out at Annexure A. ACN/ARSN (if applicable) This notice is given by HNA Tourism Group Co., Ltd (海航旅业集团有限公司)on behalf of itself and each of the other entities named in the list of 1 pages annexed to this notice and marked A. The holder became a substantial holder on 23/06/2016 – 14/08/2017 1 2. Details of voting power The total number of votes attached to all the voting shares in the company or voting interests in the scheme that the substantial holder or an associate (2) had a relevant interest (3) in on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Class of Number of securities Person’s votes (5) Voting power (6) securities (4) ORD 1,676,736,791 1,676,736,791 19.82% 3. Details of relevant interests The nature of the relevant interest the substantial holder or an associate had in the following voting securities on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Holder of relevant interest Nature of relevant interest (7) Class and number of securities HNA Tourism (International) Investment Group Co., Ltd. acquired 60% of the issued capital of HNA Innovation Ventures (Hong Kong) Co., Limited on 14 August 2017 due to internal HNA Tourism (International) Investment restructuring (as described further at Annexure ORD 1,676,736,791 Group Co., Ltd. -

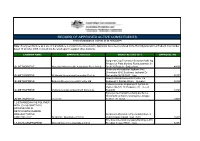

RECORD of APPROVED ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS This Information Is Current As at 19/02/2014

RECORD OF APPROVED ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS This information is current as at 19/02/2014 Note: Evergreen Nurture as a site of manufacture is known to be non-existent. Approvals have been restored to the Record pursuant to a Federal Court Order dated 13 October 2008. It should not be relied upon to support other products. COMMON NAME APPROVAL HOLDER MANUFACTURE SITE APPROVAL NO. Syngenta Crop Protection Schweizerhalle Ag Production Plant Muttenz Rothausstrasse 61 (S)-METHOPRENE Novartis Animal Health Australasia Pty. Limited Ch-4133 Pratteln Switzerland 44095 Wellmark International Jayhawk Fine Chemicals 8545 Southeast Jayhawk Dr (S)-METHOPRENE Wellmark International (australia) Pty Ltd Galena Ks 66739-0247 Usa 55179 Babolna Bioenvironmental Centre Ltd (S)-METHOPRENE Babolna Bioenvironmental Centre Ltd Budapest X Szallas Utca 6 Hungary 58495 Vyzkumny Ustav Organickych Syntez As Rybitvi 296 532 18 Pardubice 20 Czech (S)-METHOPRENE Vyzkumny Ustav Organickych Zyntez As Republic 59145 Synergetica-changzhou Gang Qu Bei Lu Weitang New District Changzhou Jiangsu (S)-METHOPRENE Zocor Inc 213033 Pr China 59428 1,2-ETHANEDIAMINE POLYMER WITH (CHLOROMETHYL) OXIRANE AND N- METHYLMETHANAMINE MANUFACTURING Buckman Laboratories Pty Ltd East Bomen CONCENTRATE Buckman Laboratories Pty Ltd Road Wagga Wagga Nsw 2650 56821 The Dow Chemical Company Building A-915 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE Dow Agrosciences Australia Limited Freeport Texas 77541 Usa 52481 COMMON NAME APPROVAL HOLDER MANUFACTURE SITE APPROVAL NO. Dow Chemical G.m.b.h. Werk Stade D-2160 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE Dow Agrosciences Australia Limited Stade Germany 52747 Agroquimicos De Levante (dalian) Company Limited 223-1 Jindong Road Jinzhou District 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE Agroquimicos De Levante, S.a. -

Yichang to Badong Expressway Project

IPP307 v2 World Bank Financed Highway Project Yiba Expressway in Hubei·P. R. China YBE_05 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yichang to Badong Expressway Project Social Assessment Report Final Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Financed Project Office of HPCD Social Survey Research Center of Peking University 22 September 2008 1 Preface Entrusted by the World Bank Financed Project Execution Office (PEO) under the Hubei Provincial Communications Department (HPCD), the Social Survey Research Center of Peking University (SSRCPKU) conducted an independent assessment on the “Project of the Stretch from Yichang to Badong of the Highway from Shanghai to Chengdu”. The Yiba stretch of the highway from Shanghai to Chengdu is lying in the west of Hubei Province which is at the joint of middle reaches and upper reaches of the Yangtze River. The project area administratively belongs to Yiling District Yichang City, Zigui County, Xingshang County and Badong County of Shien Tujia & Miao Autonomous Prefecture. It adjoins Jianghan Plain in the east, Chongqing City in the west, Yangtze River in the south and Shengnongjia Forest, Xiangfan City etc in the north. The highway, extending 173 km, begins in Baihe, connecting Jingyi highway, and ends up in Badong County in the joint of Hubei and Sichuan, joining Wufeng highway in Chongqing. Under the precondition of sticking to the World Bank’s policy, the social assessment is going to make a judgment of the social impact exerted by the project, advance certain measures, and in the meanwhile bring forward supervision and appraisement system. During July 1st and 9th, 2007, the assessment team conducted the social investigation in Yiling District Yichang City, Zigui County, XingshanCounty and Badong County. -

Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in Figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011

37 Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 FAO WATER Irrigation in Southern REPORTS and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 37 Edited by Karen FRENKEN FAO Land and Water Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2012 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107282-0 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

A Spatial Distribution Equilibrium Evaluation of Health Service Resources at Community Grid Scale in Yichang, China

sustainability Article A Spatial Distribution Equilibrium Evaluation of Health Service Resources at Community Grid Scale in Yichang, China Jingyuan Chen 1, Yuqi Bai 1,2,3,* , Pei Zhang 4,*, Jingyuan Qiu 2, Yichun Hu 5, Tianhao Wang 6, Chengzhong Xu 4 and Peng Gong 2,3 1 Faculty of Innovation and Design, City University of Macau, Taipa, Macau 999078, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Earth System Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] (J.Q.); [email protected] (P.G.) 3 Center for Healthy Cities, Institute for China Sustainable Urbanization, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100875, China 4 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Yichang 443000, China; [email protected] 5 Smart City Construction Office, Yichang 443000, China; [email protected] 6 Big Data Management Center, Yichang 443000, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.B.); [email protected] (P.Z.) Received: 11 November 2019; Accepted: 16 December 2019; Published: 19 December 2019 Abstract: Whether the supplies of health services and related facilities meet the demand is a critical issue when developing healthy cities. The importance of health services and related facilities in public health promotion has been adequately proved. However, since the community population and resource data are usually available at the scale of an administrative region; it is very difficult to perform further fine-scaled spatial distribution equilibrium evaluation studies. Such kinds of activities are highly expected for precise urban planning and management. Yichang is located in Hubei province, the central part of China, along the Yangzi River. It is leading both of China’s smart cities demonstration project and China’s healthy cities pilot project. -

Appropriate Flow Forecasting for Reservoir Operation

Appropriate flow forecasting for reservoir operation Promotion committee: prof. dr. ir. H.J. Grootenboer University of Twente, chairman/secretary prof. dr. S.J.M.H. Hulscher University of Twente, promotor dr. ir. C.M. Dohmen-Janssen University of Twente, assistant promotor dr. ir. M.J. Booij University of Twente, assistant promotor prof. dr. Y. Chen SunYat-Sen University prof. dr.ir. A.Y. Hoekstra University of Twente prof. dr. ir. A.E. Mynett UNESCO-IHE / WL | Delft Hydraulics prof. dr. ir. C.B. Vreugdenhil University of Twente prof. dr. Z. Su ITC / University of Twente Cover: Part of the Geheyan Reservoir on Qingjiang River in China (used as a case study in Chapter 2 in this dissertation), by courtesy of Xinyu Lu. ISBN 90-365-2226-9 Copyright © 2005 by Xiaohua Dong All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the author. Printed by PrintPartners Ipskamp BV, Enschede, the Netherlands APPROPRIATE FLOW FORECASTING FOR RESERVOIR OPERATION DISSERTATION to obtain the doctor’s degree at the University of Twente, on the authority of the rector magnificus, prof.dr. W.H.M. Zijm, on account of the decision of the graduation committee, to be publicly defended on Wednesday 24 August 2005 at 15.00 by Xiaohua Dong born on 7 January, 1972 in Zigui county, China This dissertation has been approved by the promotor prof. dr. S.J.M.H. Hulscher and the assistant promotors dr.