The Spirit of 1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

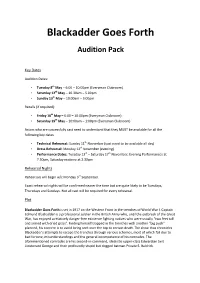

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

TEXT-PS-122-Anthology.Pdf

Teachers & Writers Collaborative Spring 2018 T&W Collaborative Teaching Artist: Olaya Barr NYU Education Associate: India Gonzalez PS/IS 122Q Academy for the Intellectually Gifted Principal: Anna Aprea Assistant Principals: Alba Carlucci & Michael Pascarelli 6th-Grade ELA Teacher (Classes 506, 501, 509 & 504): Irene Pappas 1 To see your young author published in our magazine please visit teachersandwritersmagazine.org. TEACHERS & WRITERS COLLABORATIVE (T&W) partners with New York City schools and community-based organizations to offer dynamic creative writing programs led by professional writers. Since 1967, T&W has worked with more than 750,000 K-12 students and more than 25,000 teachers at schools throughout New York City; published more than 80 books and an online magazine about creative writing education; and provided free resources for students, teachers, and writers on our website (www.twc.org). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This residency was sponsored by New York City Department of Education, E.H.A. Foundation, and Teachers & Writers Collaborative (T&W). T&W programs are made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. T&W is also grateful for support from the following: Amazon.com, Aroha Philanthropies, Bay and Paul Foundations, Bydale Foundation, Cerimon Fund, Charles Lawrence Keith and Clara Miller Foundation, Con Edison, E.H.A. Foundation, Hans and Ruth Cahnmann Family Fund, ING Financial Services, Jerome Foundation, Kenneth Koch Literary Estate, Laura B. -

February 2018 Pits Close and a Strike Is Called

01.cover_Layout 1 08/02/2018 15:47 Page 1 02.specsavers_Layout 1 07/02/2018 16:56 Page 1 03.contents_contents june 06.qxd 07/02/2018 17:26 Page 1 WELCOME TO BREEZE Feel the Breeze! Well, here we are in the midst of many changes up and down the country and we’ve been busy too! BUSINESS OWNERS Want to let the community around you We’ve been around now for no less than fifteen years and in that time know you are here - then contact our team we have received such a warm reception from our loyal readers. and be a part of the Breeze success. Sometimes though it is time for a ‘spring clean’ so here we are with our Just call Sandra on 07967 282558 refreshed design and improved content. We are still here as your No.1 favourite community magazine! READERS - Enjoy reading about local clubs & events We are online as well don’t forget, giving you the chance to look up back and tell us about yours - we’ll do our best issues and see what we’ve covered over the year so don’t worry if you to promote your community. And don’t ever misplace us - we’re on facebook or simply pop online at forget to support your local businesses - www.breeze-magazine.co.uk mention you saw them here in Breeze! Are you a reader with an idea of what you want to see in the magazine? Do you have an interesting activity or run a local club in our area? Well why not get in touch? Just email us on [email protected] OUR CONTACTS: If you are one of the many local business who kindly choose us to Advertising Sales: 07967 282 558 advertise your business then we hope you also like our new look - e: [email protected] a superb media format for telling Breeze readers about what you do! Editorial for clubs / charities etc: Facebook Page - Look for Breeze Magazine, like us and share your page on ours e: [email protected] Now available to read on Smart phones & Tablets. -

Downloaded 2021-10-02T20:08:21Z

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Where Does Law Come From? Authors(s) Casey, Gerard Publication date 2010-12 Publication information Philosophical Inquiry, 32 (3-4): 85-92 Publisher Philosophy Documentation Center Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/5108 Publisher's version (DOI) 10.5840/philinquiry2010323/45 Downloaded 2021-10-02T20:08:21Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Where Does Law Come From? Gerard Casey University College Dublin Dublin 4, Ireland Ph. 353 1 716 8201 Email. [email protected] 1 Abstract Law, like language, is the product of social evolution, embodied in custom. The conditions for the emergence of law—embodiment, scarcity, rationality, relatedness and plurality—are outlined, and the context for the emergence of law—dispute resolution— is analysed. Adjudication procedures, rules and enforcement mechanisms, the elements of law, emerge from this context. The characteristics of such a customarily evolved law are its severely limited scope, its negativity, and its horizontality. It is suggested that a legal system (or systems) based on the principles of archaic law could answer the needs of social order without permitting the paternalistic interferences with liberty characteristic of contemporary legal systems. 2 I: Introduction In the darkest days of World War I, the following conversation took place in the trenches between the courage-challenged but cynical Captain Blackadder and the intelligence- challenged but phlegmatic Private Baldrick. -

For King and Country: Reconsidering the Great War Soldier in Britain, 1914-1945

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 For King and Country: Reconsidering the Great War Soldier in Britain, 1914-1945 Nicholas John Schaefer University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Schaefer, Nicholas John, "For King and Country: Reconsidering the Great War Soldier in Britain, 1914-1945" (2017). Master's Theses. 297. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/297 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOR KING AND COUNTRY: RECONSIDERING THE GREAT WAR SOLDIER IN BRITAIN, 1914-1945 by Nicholas John Schaefer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 FOR KING AND COUNTRY: RECONSIDERING THE GREAT WAR SOLDIER IN BRITAIN, 1914-1945 by Nicholas John Schaefer August 2017 Approved by: ________________________________________________ Dr. Allison Abra, Committee Chair Assistant Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Andrew A. Wiest, Committee Member Distinguished Professor, History ________________________________________________ -

Faith in Conflict: a Study of British Experiences in the First World War with Particular Reference to the English Midlands

FAITH IN CONFLICT: A STUDY OF BRITISH EXPERIENCES IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS by STUART ANDREW BELL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham January 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The thesis addresses the question, ‘How did the First World War affect the religious faith of the people of Britain?’ The ways in which wartime preachers, hymn-writers, diarists and letter-writers expressed their faith are examined. For the vast majority, the War was both a military and a spiritual conflict of right against might and the rhetoric of a Holy War was popular. Questions of divine omnipotence and providence troubled many, the standard response being that war was a consequence of God’s gift of free will. The language of sacrifice dominated public discourse, with many asserting that the salvation of the fallen was ensured by their own sacrifice. -

Open Rshafer Doctoraldissertation Creaturecomforts Revisedandformatted.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts CREATURE COMFORTS: THE EXCHANGE AND CONSUMPTION OF SUGAR, TOBACCO, AND OTHER EVERYDAY STIMULANTS DURING THE GREAT WAR A Dissertation in History by Robert W. Shafer © 2014 Robert W. Shafer Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 The dissertation of Robert W. Shafer was reviewed and approved* by the following: Sophie De Schaepdrijver Associate Professor of History Dissertation Adviser and Committee Chair Philip Jenkins Emeritus Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Humanities Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History Daniel Purdy Professor of German Studies Jonathan Brockopp Associate Professor of History and Religious Studies Director of Graduate Studies in History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This project explores the mobilization efforts undertaken during the First World War in their broadest sense. No war to date required nor mobilized the amount of materiél that was consumed from 1914-1918. These efforts included not only the physical organization and deployment of men and supplies. Recent scholarship has shown that morale was also mobilized and remobilized during the war. This study focuses on where these efforts converge: the use of everyday psychoactive stimulants and their effects on morale at the front, and the economic mobilization of these goods and industries en masse. As such, this project highlights the importance of a variety of agricultural products that are quite unnecessary to human subsistence, but have nonetheless come to be considered indispensable from everyday consumption. These ordinary goods include sugar, tobacco, coffee, tea, as well as alcoholic beverages. -

Sunhelmet Sue by the Same Author

ERICK BERRY CrOPmiGHT DEPOSIT. SUNHELMET SUE BY THE SAME AUTHOR GIRLS IN AFRICA BLACK FOLK TALES PENNY WHISTLE HUMOO THE HIPPO AND LITTLE BOY BUMBO ILLUSTRATIONS OF CYNTHIA JUMA OF THE HILLS CAREERS OF CYNTHIA SOJO MOM DU JOS THE WINGED GIRL OF KNOSSOS STRINGS TO ADVENTURE THE HOUSE THAT JILL BUILT (AlHie MaXOIl) > If far treasure the c&vewis just tfte place!” SUNHELMET SUE Eric\ Berry Boston 1936 New Yor\ LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD COMPANY Copyright, 1936, by LOTHROP, LEE AND SHEPARD COMPANY All rights reserved. No part of this book may be re¬ produced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in magazine or newspaper. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA £' GClA 971G9 3 ~ f J For ‘Dorinda’ in appreciation of charm and courage Contents CHAPTER PAGE I. Stowaway .... II II. A Parachute Jump to Africa 31 III. By Cargo Boat to Nigeria 50 IV. The Sunhelmet becomes a Fixture 64 V. To Yar?. 72 VI. The Secretary Hires a Secretary 8l VII. Alone in Africa 93 VIII. The Little Judge . 109 IX. Wet Squeeze .... 117 X. On the Trail of Yar . 123 XI. To Yar by a Shoot-the-Shoot 133 XII. Long Ago a Great City 144 XIII. Another Archaeological Trip 151 XIV. Evil Spirits .... 158 XV. The Heroine of Katsina 172 XVI. A Real Discovery . 186 XVII. Yar Yields up a Secret 204 XVIII. The Flight Again . 213 XIX. Lost: Rum a Cave . 224 XX. -

The First World War in British Theatre

The First World War in British Theatre Nathan Gregory Finger Macquarie University, Department of English In the Somme valley, the back of language broke. It could no longer carry its former meanings. World War I changed the life of words and images in art, radically and forever. —ROBERT HUGHES This thesis is submitted to Macquarie University in fulfilment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy in English. The work is entirely my own and has not been submitted elsewhere for examination. Signed: Nathan Finger Date: ii Acknowledgments First and foremost thanks must go to Paul for the guidance and advice you gave every step of way, especially in the wayward early days of this project. Without your help I’m quite certain I never would have made it. Second, to the people who endured living with me during this process. Anita, Tom and Angela, that means you guys. You fed me and provided much needed social interaction. But let’s face it, I really am the perfect housemate. My comrade throughout all of this, Jenn. Whenever confusion set in, or things looked dark, or I needed a second opinion on when to use a hyphen, you were always there. I can’t imagine having done this without you. I think it made all the difference. And finally, Mum and Dad, for a hundred thousand reasons that could never be listed. For everything. iii Abstract More than a century since its declaration, the First World War is universally accepted as one of the defining events of the twentieth century. Socially, politically, economically and culturally the war is viewed as having been a watershed and marks the boundary between all facets of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. -

Concerted Applications of Gas Electron Diffraction and Computational Chemistry

Structure and Dynamics by Experiment and Theory: Concerted Applications of Gas Electron Diffraction and Computational Chemistry Conor Douglas Rankine Doctor of Philosophy University of York Chemistry June 2019 To everyone in the C/A/057 Phys. Chem. Office: “Well …whatever [your plan] was, I’m sure it was better than my plan to get out of all this by pretending to be mad. I mean, who would have noticed another madman ‘round here?” Edmund Blackadder. “Goodbyeee”. Blackadder Goes Forth. BBC. 2 Nov. 1989. ii Abstract To plan and prepare the strongest research proposals for time-resolved gas electron diffraction (TRGED) experiments, the author has launched and overseen the development of two new research programmes in the Wann Electron Diffraction Group. A time-averaged gas electron diffraction (GED) programme has seen the technique re- established in the UK following the relocation, recommission, and modernisation of a 1960s gas electron diffractometer. Two case studies – a) 4-(dimethylamino)benzonitrile, and b) tinII bis(trifluoroacetate), ditinII μ-oxy-bis-μ-trifluoroacetate, and tinIV tetrakis(trifluoroacetate) – highlight the range of chemical samples that are accessible to study using the upgraded gas electron diffractometer. A computational chemistry programme has seen trajectory surface-hopping dynamics (TSHD) introduced to the Wann Electron Diffraction Group, delivering a paradigm shift in the ability of the research group to plan and interpret TRGED experiments. Parallel Python code has been developed to simulate TRGED data and benchmarked with up to 64 CPU cores as part of this programme. High performance is achieved in the strong and weak parallel scaling regimes. The interplay between the two programmes is illustrated in three case studies: the photolysis of 1,2-diiodotetrafluoroethane, the photofission of the disulfide bond in 1,2-dithiane, and the photoisomerisation of E-cinnamonitrile. -

INVESTIGATING the STYLE, FORM and GENRE of PERIOD DRAMA in 2010S BRITISH TELEVISION

A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2020 HERITAGE AND POST-HERITAGE: INVESTIGATING THE STYLE, FORM AND GENRE OF PERIOD DRAMA IN 2010s BRITISH TELEVISION WILL STANFORD This image is unavailable. Please consult reference on page ii for further information. ABBISS ii ABSTRACT This project analyses six period drama productions in British television of the 2010s, expanding Claire Monk’s term of ‘post-heritage’ into a critical framework. Its case studies establish a cycle of progressive representations of the past in recent television drama, which operate against the assumptions of ‘heritage’ nostalgia forwarded by earlier scholars. The post-heritage framework consists of five guiding elements: interrogation, subversion, subjectivity, self-consciousness and ambiguity. These inform the analysis of the project’s case studies, while also allowing the existence of post-heritage elements to be recognised in earlier period drama productions. The thesis is split into three distinct parts, which allow the heritage and post-heritage elements of the case studies to be associated with the characteristics and theoretical concepts of television drama. The first chapter of each part evaluates the institutional context of its case study, identifying its impact upon production through textual examples from the programme. The second chapter of each part focuses on close analysis, demonstrating the extent to which post- heritage elements can assist innovation in television drama. Part I focuses on televisual style, identifying the naturalist, realist and modernist aesthetics of television drama. Scholarly sources are used to connect these with periods of British television history. -

Intelligence Corps Meadows? 16

N il Desperandum Published for Haywards Heath & District Probus Club ISSUE 8 November 2020 Isolated but not alone Picture Credit: "Inverse proportions" by GB_Teddy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Index: 10. What does Pedagogy mean? 1. Oh, Dear God (or) Oh Dear, God 10. Some Jigsaws are difficult 1. Humour 11. What is a vomitirium? 1. Ants aren’t going to be hungry 11. What’s a ‘Pathogen’? 2. The True Story of the American Frontier's First 11. Social Distancing in the Animal World Gunfighter 12. Mennonite Trickster and Dramatic Hero 3. Rat empathy is surprisingly like human empathy 13. Is this the best speech ever? 3. Step up your walking game 14. How to Tell a Story 4. What has happened to all our English Wild Flower 15. Intelligence Corps Meadows? 16. A big black hole: It’s very hungry 4. Warfare History Network 16. Black History Month: Postboxes painted to honour 5. Pause for thought black Britons 5. Snappy one-liners (keep a straight face) 17. Lost Love 6. A young monk arrives at the Monastery… 17. Libel vs. Slander: What’s the difference? 7. The year 1985 18. Donald Trump 8. Random excerpts from Blackadder 19. 5 key dates in the Battle of Britain 9. ‘Pragmatic’ versus ‘Dogmatic’: What’s the Difference? 20. Has Social Distancing gone mad? 9. Pragmatic Quotations 20. Airbus and Commercial Hydrogen Planes 10. What happened next? 20. Dad’s Army 10. Wild Bison in Kent 21. Finish with a giggle Nil Desperandum ISSUE 8 November 2020 Isolated but not alone Oh, Dear God (or) Oh Dear, God It doesn’t seem right, that with all of your might, You haven’t observed yet, in man’s efforts to know you, we created thousands* of faiths, each claiming to be true, each one says and believes they are the closest to you.