Oman Foreign Policy Towards the Arab Spring in the Framework of Strategic Hedging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amir Mourns H M Sultan Qaboos

www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 24 | Number 8134 SUNDAY 12 JANUARY 2020 17 JUMADA I - 1441 2 RIYALS BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 ARTIC expands Rublev wins operational Qatar hotel portfolio ExxonMobil in Qatar Open Enjoy unlimited local data and calls with the new Qatarna 5G plans Amir, Putin hold phone talks, Amir mourns H M Sultan Qaboos discuss regional Qatar announces ‘Oman to continue path developments three days of QNA — DOHA mourning This is a sad day for all the Gulf people, as for the laid by Sultan Qaboos’ brothers in Oman. With great sorrow, we received in Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Qatar the news of the departure of Sultan Qaboos to the QNA — MUSCAT set by the late H M Sultan Hamad Al Thani held a tele- QNA — DOHA mercy of Allah The Almighty, leaving behind a rising Qaboos in bolstering cooper- phone conversation yesterday country and a great legacy that everyone cherishes. It is H M Sultan Haitham bin ation with brothers in the GCC with H E President Vladimir Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin a great loss for the Arab and Islamic nations. We offer Tariq bin Taimur Al Said was and the Arab world without Putin of the friendly Russian Hamad Al Thani mourned condolences to the brotherly Omani people and we pray announced as the new Sultan interfering in the affairs of Federation. yesterday the death of H M to Allah for His Majesty the Supreme Paradise. of Oman, in succession to the others. Peace and coexistence During the phone call, they Sultan Qaboos bin Said bin late H M Sultan Qaboos bin will remain as cornerstones of discussed a number of regional Taimur of the Sultanate of and international issues of Oman, who passed away on common concern, especially Friday evening. -

Oman Succession Crisis 2020

Oman Succession Crisis 2020 Invited Perspective Series Strategic Multilayer Assessment’s (SMA) Strategic Implications of Population Dynamics in the Central Region Effort This essay was written before the death of Sultan Qaboos on 20 January 2020. MARCH 18 STRATEGIC MULTILAYER ASSESSMENT Author: Vern Liebl, CAOCL, MCU Series Editor: Mariah Yager, NSI Inc. This paper represents the views and opinions of the contributing1 authors. This paper does not represent official USG policy or position. Vern Liebl Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University Vern Liebl is an analyst currently sitting as the Middle East Desk Officer in the Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning (CAOCL). Mr. Liebl has been with CAOCL since 2011, spending most of his time preparing Marines and sailors to deploy to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and other interesting locales. Prior to joining CAOCL, Mr. Liebl worked with the Joint Improvised Explosives Device Defeat Organization as a Cultural SME and, before that, with Booz Allen Hamilton as a Strategic Islamic Narrative Analyst. Mr. Liebl retired from the Marine Corps, but while serving, he had combat tours to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen, as well as numerous other deployments to many of the countries of the Middle East and Horn of Africa. He has an extensive background in intelligence, specifically focused on the Middle East and South Asia. Mr. Liebl has a Bachelor’s degree in political science from University of Oregon, a Master’s degree in Islamic History from the University of Utah, and a second Master’s degree in National Security and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College (where he graduated with “Highest Distinction” and focused on Islamic Economics). -

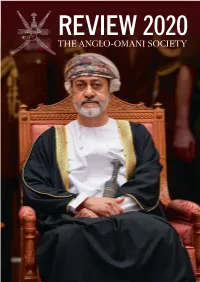

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

University of London Oman and the West

University of London Oman and the West: State Formation in Oman since 1920 A thesis submitted to the London School of Economics and Political Science in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Francis Carey Owtram 1999 UMI Number: U126805 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U126805 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 bLOSiL ZZLL d ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the external and internal influences on the process of state formation in Oman since 1920 and places this process in comparative perspective with the other states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. It considers the extent to which the concepts of informal empire and collaboration are useful in analysing the relationship between Oman, Britain and the United States. The theoretical framework is the historical materialist paradigm of International Relations. State formation in Oman since 1920 is examined in a historical narrative structured by three themes: (1) the international context of Western involvement, (2) the development of Western strategic interests in Oman and (3) their economic, social and political impact on Oman. -

Suddensuccession

SUDDEN SUCCESSION Examining the Impact of Abrupt Change in the Middle East SIMON HENDERSON EDITOR REUTERS Oman After Qaboos: A National and Regional Void The ailing Sultan Qaboos bin Said al-Said, now seventy-nine years old, has no children and no announced successor, with only an ambiguous mechanism in place for the family council to choose one. This study con- siders the most likely candidates to succeed the sultan, Oman’s domestic economic challenges, and whether the country’s neutral foreign policy can survive Qaboos’s passing. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY POLICY NOTE 74 DECEMBER 2019 SUDDEN SUCCESSION: OMAN In November 2019, while presiding over Oman’s TABLE 1. ILL-FATED OMANI SULTANS National Day celebration at the Wudam naval base, Thuwaini bin r. 1856–66 Killed in his sleep by his Sultan Qaboos bin Said, who has ruled his country Said son Salem bin Thuwaini for nearly five decades, looked particularly frail. It was correspondingly of little surprise that on December 7 he Salem bin r. 1866–68 Deposed by his cousin departed for Belgium to undergo a series of medical Thuwaini Azzan bin Qais tests at Leuven’s University Hospitals. In 2014–15, the Azzan bin r. 1868–71 Not recognized by British; sultan spent eight months in Germany while receiving Qais killed in battle apparently successful treatment for colon cancer. But his latest trip abroad coincided with rumors of a signifi- Taimur bin r. 1913–32 Abdicated to his son Said Faisal bin Taimur under pressure cant deterioration in his health.1 Although he has now returned to Oman, the prognosis for any seventy-nine- Said bin r. -

Deputy Amir Offers Condolences to Sultan of Oman

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 QNB posts QR14.4bn net profi t in 2019; suggests Al-Attiyah slashes Sainz’s 60% cash dividend Dakar lead to 24 seconds published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11428 January 15, 2020 Jumada I 20, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets Bosnian envoy Deputy Amir off ers condolences to Sultan of Oman His Highness the Deputy Amir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani and HE the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa al-Thani in Muscat to off er their condolences to Sultan Haitham bin Tariq bin Taimur of Sultanate of Oman on the death of Sultan Qaboos bin Said bin Taimur yesterday. QNA ily, senior offi cials and dignitaries, Fatik bin Fahar al-Said, ambassador Later in the day, Sultan Haitham Muscat praying to the Almighty Allah to have of Qatar to Oman Sheikh Jassim bin met with HE the Speaker of the Shura mercy on the soul of Sultan Qaboos Abdulrahman al-Thani and the Qatari Council Ahmed bin Abdullah bin Zaid and to rest it in paradise, and to grant embassy staff . al-Mahmoud and the delegation ac- is Highness the Deputy Amir patience and solace to his family. The Deputy Amir was accompanied companying him at the Al Alam Palace. Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al- HE the Prime Minister and Minister by HE Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser and HE the Speaker off ered his condo- His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met the outgoing HThani off ered condolences to of Interior Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser a number of ministers. -

Oman and Japan

Oman and Japan Unknown Cultural Exchange between the two countries Haruo Endo Oman and Japan and Endo Oman Haruo Haruo Endo This book is basically a translation of the Japanese edition of “Oman Kenbunroku; Unknown cultural exchange between the two countries” Publisher: Haruo Endo Cover design: Mr Toshikazu Tamiya, D2 Design House © Prof. Haruo Endo/Muscat Printing Press, Muscat, Oman 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the copyright owners. Oman and Japan Unknown Cultural Exchange between the two countries Haruo Endo Haruo Endo (b.1933), Oman Expert, author of “Oman Today” , “The Arabian Peninsula” , “Records of Oman” and Japanese translator of “A Reformer on the Throne- Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al Said”. Awarded the Order of HM Sultan Qaboos for Culture, Science and Art (1st Class) in 2007. Preface In 2004, I was requested to give a lecture in Muscat to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the establishment of the Oman-Japan Friendship Association, sponsored jointly by the Oman-Japan Friendship Association, Muscat Municipality, the Historical Association of Oman and the Embassy of Japan. It was an unexpected honour for me to be given such an opportunity. The subject of the lecture was “History of Exchange between Japan and Oman”. After I had started on my preparation, I learned that there was no significant literature on this subject. I searched for materials from scratch. I then organized the materials relating to the history of human exchange, the development of trade since the Meiji period (1868-1912) and the cultural exchanges between both countries. -

Oman in Focus 2010 Final.Pdf

Advisory services Concept to commissioning Ambassador’s Desk Feasibility studies Basic engineering FEED Detailed engineering EPCM services Oman’s 40th National Day PMC services Procurement solutions Pipelines Offshore topsides LNG, LPG, CNG Petroleum storage facilities Refineries Petrochemicals facilities Onshore surface facilities Heavy oil processing Clean development mechanism Carbon capture and storage Kapoor Deepak : Photo would like to share with you Sultanate of Oman’s historic tryst with the Renaissance which began I exactly 40 years ago. This new dawn of progress and prosperity has been remarkable. His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said had promised to transform the country “‘into a prosperous one with a bright future”’ and called on people to work in unity and cooperation for transforming the future of the nation. It turned into reality, as we celebrate the big achievement. This month of November,GLOBAL our beloved country Oman, SKILLS, commemorates the 40th anniversary of its National Day. It is a moment to celebrate not only the triumphs and achievements, but also the grandeur of the striving, the efforts LOCALbehind it, and the vision andEXPERTISE ideals which moulded it. Oman has made remarkable strides towards the development of its human resources which, in turn, has significantly contributed to its social development and economic growth. 0RWW_0DF'RQDOG_LV_D_JOREDO_PDQDJHPHQW__HQJLQHHULQJ_DQG_GHYHORSPHQW_FRQVXOWDQF The Economy was WXUQRYHU_RI_…ranked fourth in the__ELOOLRQ_DQG_RYHU________VWDII_RSHUDWLQJ_LQ_____FRXQWULHV__)RU_RYHU____ -

A Great Loss for Arab, Islamic World: Amir Haitham Named New Sultan of Oman QNA Muscat

SUNDAY JANUARY 12, 2020 JUMADA AL-AWWAL 17, 1441 VOL.13 NO. 4840 QR 2 Fajr: 5:01 am Dhuhr: 11:42 am Asr: 2:43 pm Maghrib: 5:04 pm Isha: 6:34 pm MAIN BRANCH LULU HYPER SANAYYA ALKHOR World 8 Business 9 Doha D-Ring Road Street-17 M & J Building Trump will try to block High-profile events to drive PARTLY CLOUDY MATAR QADEEM MANSOURA ABU HAMOUR BIN OMRAN HIGH : 20°C Near Ahli Bank Al Meera Petrol Station Al Meera Bolton impeachment hotel occupancy higher: LOW : 14°C alzamanexchange www.alzamanexchange.com 44441448 testimony QNTC official Amir MOURNS HM SULTAN QABOOS, OFFers CONDOleNCes A great loss for Arab, Islamic world: Amir Haitham named new Sultan of Oman QNA MUSCAT HAITHAM bin Tariq bin Taimur al Said was named as the new Sultan of the Sultan- ate of Oman. He succeeds Sul- tan Qaboos bin Said who died on Friday evening. A statement issued by Oman’s Defence Council said that Sultan Qaboos had chosen Haitham bin Tariq bin Taimur Amir declares three days of public mourning in Qatar al Said as the new Sultan in his will. The Royal Family had QNA The statement said the to have mercy on his soul and God Almighty, leaving behind communicated to the Defence DOHA news of HM Sultan Qaboos to rest it in peace in paradise a rising country and a great Council that they had appoint- bin Said bin Taimur’s passing along with martyrs and the legacy that everyone cher- ed Haitham bin Tariq al Said THE Amir HH Sheikh Tamim was received with hearts filled faithful, and prayed that Al- ishes. -

Qvcs Issue Over 144,000 Visas

www.thepeninsula.qa Tuesday 14 January 2020 Volume 24 | Number 8136 19 Jumada I - 1441 2 Riyals BUSINESS | 01 SPORT | 12 NPIM acquires Handball: Team Qatar 49% equity stake embarks on Asian in Stockyard Championship Hill Wind Farm mission Enjoy unlimited local data and calls with the new Qatarna 5G plans Two DFI-backed Father Amir offers condolences to Sultan of Oman films get Oscar Father Amir H H Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa nominations Al Thani offered AP MUHAMMED AFSAL condolences to H M THE PENINSULA Sultan Haitham bin Tariq bin Taimur Al Said of Two films supported by Doha the Sultanate of Oman Film Institute have won on the death of Sultan yesterday’s Oscar nomina- Qaboos bin Said bin tions. The Cave, a Syrian civil Taimur at Al Alam Palace war film directed by Feras in Muscat yesterday. Fayyad has been nominated H H the Father Amir also in best documentary feature offered condolences to category, while Brotherhood, Their Highnesses the by Montreal-based film- members of the royal maker Meryam Joobeur won family, senior officials the nomination in best live and dignitaries, praying action short films. to the Almighty Allah to “Congratulations to the have mercy on the soul entire teams of The Cave and of Sultan Qaboos and to Brotherhood, two DFI-granted rest it in paradise, and films that earned #Oscar nom- to grant patience and inations today! #Qatar solace to his family. H H #Oscars,” Doha Film Institute the Father Amir arrived tweeted yesterday. in the Sultanate of The Cave, tells the story of Oman earlier yesterday Syrian doctor Amani Ballour morning, where he was who worked in a fortified greeted by H H Sayyid underground hospital called Fatik bin Fahar Al Said; ‘the cave’ where she and her the Ambassador of the team defied constant bom- State of Qatar to the bardments to save thousands Sultanate of Oman, of lives during the five-year H E Sheikh Jassim bin siege of eastern Ghouta region. -

A History of Modern Oman Jeremy Jones and Nicholas Ridout Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00940-0 - A History of Modern Oman Jeremy Jones and Nicholas Ridout Index More information Index abayas , 196n1 in Oman, 72 – 74 , 92 – 93 , 131 Abd al-Aziz (Saudi Amir), 45 on Zanzibar, 71 , 74 Abd al-Aziz bin Said, 87 anti-Muslim/Islam perceptions in Abdallah ibn Faisal, 77 West, 237 Abduh, Mohammed, 73 Appadurai, Arjun, 69 Abdullah, Salem, 219n16 Arab League, 123 – 124 , 153 – 154 abolitionism, 50 , 58 Arab nationalism Omani cooperation with, 58 – 59 , 86 – 87 Dhofari participation in, 137 – 138 Abu Dhabi, 107n4 , 181 – 182 and Imamate, 106 , 117 – 118 , 123 – 124 Afghanistan, Omani support for US Arab rulers, legitimacy of, 251 – 252 intervention in, 234 – 235 Arab Spring, 248 – 250 afl aj (irrigation channels), 8 – 9 in Oman, 250 – 259 Africa, see East Africa Arab-Israeli confl ict, peace process, Africans, see East Africans 215 – 218 agriculture, 8 – 9 Arabian Nights , 13 – 14 Agriculture, Fisheries and Industries Arabian Peninsula Council, 203 oil exploration in, 95 – 96 , 100 – 102 Ahmad bin Hilal (ruler of Oman), 13 British concessions/interests, 101 – 102 , Ahmad bin Said (Imam/Sultan of Oman, 104 , 110 1749–1783), 17 – 18 , 23 and Buraimi dispute, 109 , 110 Muscat captured by, 32 – 34 Arabs rise to power, 27 – 32 in Oman, 6 – 8 , 27 Ahmadinejad, Mahmoud, 243 , 245 trade with China, 12 – 13 Al Bu Said dynasty, 2 , 87 Aramco Oil Company, 107 and constitutional monarchy, 227 – 228 Azd Arabs, 6 – 7 , 27 founding of, 17 – 18 , 23 Azzan bin Qays (Imam of Oman, and Ibadism, 10 1868–1871), 72 , 75 -

The Solitary Sultan and the Construction of the New Oman

Chapter 19 The solitary sultan and the construction of the new Oman John E Peterson On the surface, and to the casual visitor or observer, governing Oman undoubtedly would seem to be a snap. The country is so quiet that virtually no mention of Oman ever seems to reach most of the outside world—apart from glowing articles in travel pages of newspapers (one European journalist some years ago described the Sultanate as an 'Islamic California'). The present sultan, Qaboos bin Said of the Al Said family, has ruled since 1970, benevolently and almost single-handedly. Of course, though, there is more to Oman, to the Sultanate, and to governing the country than appears casually. Despite its present peaceful demeanour, Oman has had until recently something of a turbulent past. From early in the twentieth century until the mid-1950s, the interior was autonomous of the coast. When the present ruler's father occupied the interior in 1955, with the help of British forces, a complex and sustained civil war ensued. Although the ruler was able to assert effective control over the interior by 1959, insurgent activities and political opposition did not cease fully until after 1970.' The situation in the south, the Dhufar region, was at the same time more isolated but more serious. Annexed to the Sultanate in the nineteenth century, Dhufar gave the appearance of being more attached to Yemen than Oman. Opposition to the exceedingly paternalistic rule of the region by the present sultan's father began to emerge in the early 1960s. By the end of that decade, a full-scale rebellion was under way, led by a Marxist leadership whose goal was to overthrow all the Arab monarchies of the Gulf.