ENCYCLOPEDIA of CHRISTIAN EDUCATION Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin, Theology, Transmission, and Recurrent Impact of Landmarkism in the Southern Baptist Convention (1850-2012)

THE ORIGIN, THEOLOGY, TRANSMISSION, AND RECURRENT IMPACT OF LANDMARKISM IN THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION (1850-2012) by JAMES HOYLE MAPLES submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject CHURCH HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Supervisor: PROF M. H. MOGASHOA March 2014 © University of South Africa ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH DOCTORAL PROJECT UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Title: THE ORIGIN, THEOLOGY, TRANSMISSION, AND RECURRENT IMPACT OF LANDMARKISM IN THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION (1850-2012) Name of researcher: James Hoyle Maples Promoter: M. H. Mogashoa, Ph.D. Date Completed: March 2014 Landmarkism was a sectarian view of Baptist church history and practice. It arose in the mid-eighteenth century and was a dominant force in the first half-century of the life of the Southern Baptist Convention, America’s largest Protestant denomination. J. R. Graves was its chief architect, promoter, and apologist. He initiated or helped propagate controversies which shaped Southern Baptist life and practice. His influence spread Landmarkism throughout the Southern Baptist Convention through religious periodicals, books, and educational materials. Key Landmark figures in the seminaries and churches also promoted these views. After over fifty years of significant impact the influence of Landmarkism seemed to diminish eventually fading from sight. Many observers of Southern Baptist life relegated it to a movement of historical interest but no current impact. In an effort to examine this assumption, research was conducted which explored certain theological positions of Graves, other Landmarkers, and sects claimed as the true church by the promoters of Baptist church succession. -

Sermons Life Sketch

Sermons and Life Sketch of B.H. Carroll, D.D. Compiled by Rev. J. B. Cranfill Waco, Texas American Baptist Publication Society 1701 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. A Baptist Historical Resource Published by the Center for Theological Research at www.BaptistTheology.org ©2006 Transcription by Madison Grace Permissions: The purpose of this material is to serve the churches. Please feel free to distribute as widely as possible. We ask that you maintain the integrity of the document and the author’s wording by not making any alterations and by properly citing any secondary use of this transcription. The Center for Theological Research Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary Fort Worth, Texas Malcolm B. Yarnell, III, Director Life Sketch of B. H. Carroll J. B. Cranfill LIFE SKETCH OF B. H. CARROLL J. B. CRANFILL THERE are not many genuinely great men. To be gifted is a great endowment; but gifts are not graces. Some of the most gifted of men have possessed none of the elements of real greatness. It is only when depth of intellect and breadth of attainment are combined with greatness of heart and gentleness of spirit that there is real greatness. Dr. B. H. Carroll is, in the highest, broadest, and best sense of the term, a genuinely great man. In his gifts he towers a very giant among his fellows, while in the breadth of learning and research he ranks with the profoundest scholars of the time. But crowning all is his great heart-power, his gentleness and humility, and his consideration for the feelings of others. -

Theological Education Volume 40, Number 2 2005

Theological Education Volume 40, Number 2 2005 ISSUE FOCUS Listening to Theological Students and Scholars: Implications for the Character and Assessment of Learning for Religious Vocation Interview Study of Roman Catholic Students Frederic Maples and Katarina Schuth Interpreting Protestant Student Voices Yau Man Siew and Gary Peluso-Verdend Learning from the First Years: Noteworthy Conclusions from the Parish Experience of Recent Graduates of ATS Schools Michael I. N. Dash, Jimmy Dukes, and Gordon T. Smith To Theologians: From One Who Cares about Theology but is Not One of You Nicholas Wolterstorff ATS Luce Consultation on Theological Scholarship, May 2003 The Association of Theological Schools Crafting Research that will Contribute to Theological Education Mark G. Toulouse OPEN FORUM Academic Challenges for “Equipping the [new diverse] Saints for Ministry” Kathryn Mapes Theological Education and Hybrid Models of Distance Learning Steve Delamarter and Daniel L. Brunner A Response Regarding ATS Standard 10: Multiple Locations and Distance Education Louis Charles Willard Theological Education Index: 1964–2004 The Association of Theological Schools IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA ISSN 0040-5620 Theological Education is published semiannually by The Association of Theological Schools IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA 10 Summit Park Drive Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15275-1103 DANIEL O. ALESHIRE Executive Editor JEREMIAH J. McCARTHY Editor NANCY MERRILL Managing Editor LINDA D. TROSTLE Assistant Editor For subscription information or to order additional copies or selected back issues, please contact the Association. Email: [email protected] Website: www.ats.edu Phone: 412-788-6505 Fax: 412-788-6510 © 2005 The Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada All rights reserved. -

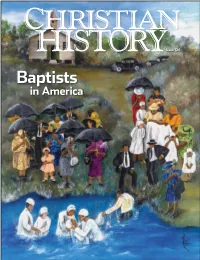

Baptists in America LIVE Streaming Many Baptists Have Preferred to Be Baptized in “Living Waters” Flowing in a River Or Stream On/ El S

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 126 Baptists in America Did you know? you Did AND CLI FOUNDING SCHOOLS,JOININGTHEAR Baptists “churchingthe MB “se-Baptist” (self-Baptist). “There is good warrant for (self-Baptist). “se-Baptist” manyfession Their shortened but of that Faith,” to described his group as “Christians Baptized on Pro so baptized he himself Smyth and his in followers 1609. dam convinced him baptism, the of need believer’s for established Anglican Mennonites Church). in Amster wanted(“Separatists” be to independent England’s of can became priest, aSeparatist in pastor Holland BaptistEarly founder John Smyth, originally an Angli SELF-SERVE BAPTISM ING TREES M selves,” M Y, - - - followers eventuallyfollowers did join the Mennonite Church. him as aMennonite. They refused, though his some of issue and asked the local Mennonite church baptize to rethought later He baptism the themselves.” put upon two men singly“For are church; no two so may men a manchurching himself,” Smyth wrote his about act. would later later would cated because his of Baptist beliefs. Ironically Brown Dunster had been fired and in his 1654 house confis In fact HarvardLeague Henry president College today. nial schools,which mostof are members the of Ivy Baptists often were barred from attending other colo Baptist oldest college1764—the in the United States. helped graduates found to Its Brown University in still it exists Bristol, England,founded at in today. 1679; The first Baptist college, Bristol Baptist was College, IVY-COVERED WALLSOFSEPARATION LIVE “E discharged -

Alumni News Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2021 with Funding from Princeton Theological Seminary Library

me eA Gren Re Sache fer >t, hatedehoneses ates ml te Mc ate tet ety atenre Nea ry De, ne an nl mtn pipe 1 he ether dn PEFR Nano Nw pags ap he Fao ber Pig Loot Saran ge Taw yore» min ae ater a he ar Pak Alpe, rel aster oii Main nat ole Pi sp oy. TaM Bros nb cloetey a San len eeee-se ie ~ - = elicit pte Date inten “gt Ne res hereto We 7 Meta a Nae Magan Fath maha eat mete ROR eae Pete eae gree mince ne Non Seng aggre Date, tee eh WO ie tierteP ae WW thet Sect eed Pw en Mee nthe Mea hn erin ne iP tetera oe ie - > %, a a eyeoe a «tthe, Ss oul AT me . a — a ate: in? oe " “ = a re > ™ i a eerie ‘ eat ain se Has i oe Re RS Raa chlarino Teta ck Itoh saree atte Racrciniomctincennen si eae A ete atete arn NER utuleeaie rae ‘ pinched fet Taha Mebx NS fate es Siete Matias ap” tyra aM Tak es yi 3 K 4 nies merpn ea Nena Aaa eae eee SA Menon ee anon Re ete Ingots eccipigy nd aibe-heapin te 7 ae hare bike tatriptpakogite Pe hone ces - Tera thay adios Pst ache ie Dali i iota Acta tettyawtn Re atehe Sicha z peace tana Serene liabestenrietiea Case . - ye wa - x - ist el areas a ea mine reer see eee eRe = pe tet. ra 0" ie arti eet ac SR ¥ ore a : haa Rate sla hen Tithe Pach terete Se be he Sin WSh PEE An ober ers Ore Serres Te fe canoe ae ete ea Se) = den? OU de oink ty ecortoae tata Spare ~ eee tere Sat rie ers Made HoMen Prt aie pag acing AL tne es Mee te by) m RB aM, Mabe Poel nM ve nh eh Pa oe He hs Ng aa he bn mn tow ho Detg xe Z farted pa See: Pa, 3 ete * arta. -

The Princeton Seminary Bulletin

G-41 THE SEMINARY BULLETIN COMMENCEMENT 1979 Holy and Unholy Fire! Daniel C. Thomas The This-Worldliness of the New Testament Paul W. Meyer The Material Assumptions of Integrative Theology: The Conditions of Experiential Church Dogmatics E. David Willis A Kentuckian Comes to Princeton Seminary Lefferts A. Loetscher Biblical Metaphors and Theological Constructions George S. Hendry VOLUME II, NUMBER 3 NEW SERIES 1979 PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY James I. McCord John A. Mackay President President Emeritus BOARD OF TRUSTEES John M. Templeton, President David B. Watermulder, Vice-President Frederick E. Christian, Secretary Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company, New York, N.Y., Treasurer James F. Anderson Dale W. McMillen, Jr. Richard S. Armstrong Earl F. Palmer Clem E. Bininger William A. Pollard Eugene Carson Blake Clifford G. Pollock Robert W. Bold Woodbury Ransom James A. Colston Mrs. William H. Rea Mrs. James H. Evans Lydia M. Sarandan John T. Galloway William H. Scheide Mrs. Charles G. Gambrell Laird H. Simons, Jr. Francisco O. Garcia-Treto Frederick B. Speakman Mrs. Reuel D. Harmon Daniel C. Thomas Ms. Alexandra G. Hawkins William P. Thompson Bryant M. Kirkland James M. Tunnell, Jr. Johannes R. Krahmer Samuel G. Warr Raymond I. Lindquist Irving A. West J. Keith Louden Charles Wright Henry Luce III Ralph M. Wyman TRUSTEES EMERITI J. Douglas Brown Weir C. Ketler John G. Buchanan Harry G. Kuch Allan Maclachlan Frew John S. Linen Henry Hird Luther I. Replogle Miss Eleanor P. Kelly The Princeton Seminary Bulletin VOL. II NEW SERIES 1979 NUMBER 3 CONTENTS Holy and Unholy Fire! Daniel C. Thomas 2I 3 President’s Farewell Remarks to Class of 1979 fames I. -

Dividing Or Strengthening

Dividing or Strengthening: Five Ways of Christianity Supplement Sources and Development by Harry E. Winter, O.M.I. Published by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. ©2003 Harry E. Winter OMI ISBN:0-9740702-0-3 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Catholic Christianity ............................................................................... 7 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Scripture Image and Implications ......................................................................................................................... 8 Current Situation, Evangelicals Becoming Catholic ............................................................................................11 Spectrum, Presbyterianism ...................................................................................................................................12 Spectrum, Catholicism .........................................................................................................................................14 Further Characteristics .........................................................................................................................................21 Current Situation ..................................................................................................................................................22 -

Final Report of the Commission on Historic Campus Representations

BAYLOR UNIVERSITY Commission on Historic Campus Representations FINAL REPORT Prepared for the Baylor University Board of Regents and Administration December 2020 Table of Contents 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 9 Part 1 - Founders Mall Founders Mall Historic Representations Commission Assessment and Recommendations 31 Part 2 - Burleson Quadrangle Burleson Quadrangle Historic Representations Commission Assessment and Recommendations 53 Part 3 - Windmill Hill and Academy Hill at Independence Windmill Hill and Academy Hill Historic Representations Commission Assessment and Recommendations 65 Part 4 - Miscellaneous Historic Representations Mace, Founders Medal, and Mayborn Museum Exhibit Commission Assessment and Recommendations 74 Appendix 1 76 Appendix 2 81 Appendix 3 82 Endnotes COMMISSION ON HISTORIC CAMPUS REPRESENTATIONS I 1 Commission on Historic Campus Representations COMMISSION CO-CHAIRS Cheryl Gochis (B.A. ’91, M.A. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. (B.A. ’74, ’94), Vice President, Human M.A. ’76), Linden G. Bowers Alicia D.H. Monroe, M.D., Resources/Chief Human Professor of American History Provost and Senior Vice Resources Officer President for Academic and Coretta Pittman, Ph.D., Faculty Affairs, Baylor College of Dominque Hill, Director of Associate Professor of English Medicine and member, Baylor Wellness and Past-President, and Chair-Elect, Faculty Senate Board of Regents Black Faculty and Staff Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. Association Gary Mortenson, D.M.A., (M.S.Ed. ’98, M.A. ’01), Professor and Dean, Baylor Sutton Houser, Senior, Student Professor and Chair, Journalism, University School of Music Body President Public Relations and New Media Walter Abercrombie (B.S. ’82, Trent Hughes (B.A. ’98), Vice Marcus Sedberry, Senior M.S.Ed. -

Download File

Maintaining Vital Connections between Faith Communities and their Nonprofits Overview Report on Project Findings EDUCATION REPORT : PHASE I Jo Anne Schneider • Isaac Morrison • John Belcher • Patricia Wittberg Wolfgang Bielefeld • Jill Sinha • Heidi Unruh With assistance from Meg Meyer • Barbara Blount Armstrong • W. Gerard Poole • Kevin Robinson Laura Polk • William Taft Stuart • John Corrado Funded by Lilly Endowment Inc Acknowledgments We wish to thank the many organizations, faith communities and community leaders that hosted this research and shared their insights with us. We would like to thank the Jewish Museum of Maryland for sharing historical documents with the project. We are also grateful for the guidance and advice from our advisory committee and product advisory committee members, with particular thanks to David Gamse, Stanley Carlson-Thies, Heidi Unruh, and Stephanie Boddie for comments on earlier drafts of this report. Special thanks to Kristi Moses and Anne Parsons for assistance with editing and proofreading. Initial research was done under the auspices of the Schaefer Center at the University of Baltimore. We would like to thank the University of Baltimore students, faculty and research associates in the Policy School and the Schaefer Center at University of Baltimore who participated and advised the project. Special thanks to UB students Suzanne Paszly, Abby Byrnes, and Atiya Aburraham for their work on the project . Funding for this project came from a generous grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. We are grateful to the foundation for its support and advice as we have developed the project. © Faith and Organizations Project, University of Maryland College Park (October 2009) Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Assessing and Enabling Eective Lay Ministry in Scotland: Lay Ministry and its Place in the Changing Reality of Scottish Catholicism FLETCHER, CATRIONA,ANNE How to cite: FLETCHER, CATRIONA,ANNE (2016) Assessing and Enabling Eective Lay Ministry in Scotland: Lay Ministry and its Place in the Changing Reality of Scottish Catholicism, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11850/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Assessing and Enabling Effective Lay Ministry in Scotland: Lay Ministry and its Place in the Changing Reality of Scottish Catholicism A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Theology and Ministry in Durham University Department of Theology and Religion by Catriona Fletcher 2016 1 Abstract The purpose of the dissertation is to assess where and how full-time, stable, lay ministry is developing in Scotland and to understand the ways in which lay ministry could grow and thrive with adequate resources and formation. -

The Evangelistic Seminary"

A White Paper from the CTR "The Evangelistic Seminary" And he said unto them, "Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men." Matthew 4:19 Christianity is perhaps best described as a twofold following after the Lord Jesus Christ. On the one hand, Jesus' first and foremost rallying cry was, "Come, follow me!" On the other hand, our Lord taught His disciples to extend that call to the world. Likewise, expressing the theme of both the Lord's premiere sermon (Mark 1:14-15 and parallels) and His final sermon, now known as the Great Commission (Matt 28:16-20), the final chapter in the New Testament tells us that the Spirit and the church must entreat, "Come and drink freely of the water of life!" (Rev 22:17). From beginning to end, there is a twofold determination in the heart of the New Testament that ought not be quenched: it includes, first, a desire to follow Christ; it includes, second, a necessarily correlative passion to call other people to follow Christ. In establishing His roving school of wannabe theologians, Jesus called the disciples to quit their prior vocation of fishing for fish and to learn, instead, to fish for human beings. The first Christian seminary, the seminary of the Apostles, presided over by Jesus Christ, was thus dedicated to evangelism. And, oh, some of those disciples were not at first what they would become when Christ had completely ushered them through His curriculum. This was a motley student body: their leader, appointed by the Lord Himself, was an ill-educated, impetuous loudmouth who went on to deny his Lord in His hour of greatest human need; another was committed to armed rebellion, though his Master identified a different way; yet a third, a betrayer, was providentially allowed by Christ to enroll. -

CONTENTS Foreword, Harry Leon Mcbeth Xvii Preface Xix List Of

CONTENTS Foreword, Harry Leon McBeth xvii Preface xix List of Abbreviations xxiii Chapter 1. CHANGING FLAGS OVER TEXAS 1 1.1 Cortez and Coronado 1 Cortez: The Enforcement of the Faith Cortez: Developing an Indigenous Catholic Faith by Force The Dominicans' Role: No Indigenous Clergy Coronado and the Seven Cities of Cibola La Salle The Baptist Perspective of Catholic Hegemony 1.2 Stephen F. Austin: "The Father of Texas" 7 The "Catholic" Contract to Live in Texas Austin's Early Capitulation to Catholicism: Austin to Jose Antonio Saucedo Questions on the Degrees of Catholic Complicity before Migration Catholic Reaction to the New Settlers Baptist Disinclination to Catholic Hegemony The Joseph Bays Incident Chapter 2. BAPTIST BEGINNINGS IN TEXAS, 1820-1840 12 2.1 Zacharius N. Morrell 12 Morrell's Call to Go to Texas Morrell's First Sermon in Texas and Decision to Remain, 1835 The First Sermon Preached in Houston Indian Fighting The First Missionary Baptist Church in Texas, 1836 2.2 Robert Emmett Bledsoe Baylor 17 Early Politics with Henry Clay Birth of the Tiger Point Church, 1840 The Baptist Principles Undergirding Baylor University The Founding and Naming of Baylor University, 1845 The Importance of R. E. B. Baylor to Z. N. Morrell Address to the Union Association 2.3 Noah Turner Byars 23 Byars's Stand against Heretical Doctrine Byars the Texas Patriot—To Arms! Byars and Revival 2.4 Daniel Parker 25 Two-Seeds in the Spirit The Effects of Daniel Parker on Texas Baptists 2.5 Thomas J. Pilgrim 30 First Sunday School in Texas Report on Sabbath Schools Chapter 3.