Player and Referee Conflicting Interests and the 2010 FIFA World Cuptm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Room with a View Cape Town Hotels and Tourism

A room with a view Cape Town hotels and tourism Publication jointly compiled by Wesgro, City of Cape Town and PwC September 2014 ©Cape Town Tourism ©Cape Town Tourism Contents Foreword by the Executive Mayor of Cape Town 1 Message by the CEO of Wesgro 3 Message by the Partner in Charge, PwC Western Cape 3 Contacts 4 Western Cape tourism in numbers 6 Our research 8 Section 1: Unpacking the Cape Town tourism sector 10 Foreign tourist arrivals 13 Bed nights spent by foreign tourists 18 Foreign direct investment in the Cape Town hotel industry 18 Recent hotel transactions 19 Average length of stay by province 19 Total foreign direct spend 19 Business tourism 20 Q&A with... 22 Enver Duminy – CEO, Cape Town Tourism Q&A with... 26 Alayne Reesberg – CEO, Cape Town Design, the implementing agency for Cape Town World Design Capital 2014 Q&A with... 28 Michael Tollman – CEO, Cullinan Holdings 2 A room with a view September 2014 Section 2: Hotel accommodation 30 Overview 32 Defining ‘hotel’ 32 Significant themes 32 Governance in the hotel industry 33 Cape Town hotels – STR statistics 34 Occupancy 34 Average daily room rate and revenue per available room (RevPAR) 35 Supply and demand 36 Q&A with... 38 John van Rooyen – Operations Director, Tsogo Sun Cape Region Q&A with... 42 David Green – CEO, V&A Waterfront Q&A with... 46 Joop Demes – CEO, Pam Golding Hospitality and Kamil Abdul Karrim – Managing Director, Pam Golding Tourism & Hospitality Consulting Section 3: List of selected hotels in Cape Town 54 ©Cape Town Tourism 4 A room with a view Photo: The Clock Tower at the September V&A Waterfront 2014 Foreword by the Executive Mayor of Cape Town The City of Cape Town is privileged to be part of this strategic publication for the hospitality industry in Cape Town. -

Vigilantism V. the State: a Case Study of the Rise and Fall of Pagad, 1996–2000

Vigilantism v. the State: A case study of the rise and fall of Pagad, 1996–2000 Keith Gottschalk ISS Paper 99 • February 2005 Price: R10.00 INTRODUCTION South African Local and Long-Distance Taxi Associa- Non-governmental armed organisations tion (SALDTA) and the Letlhabile Taxi Organisation admitted that they are among the rivals who hire hit To contextualise Pagad, it is essential to reflect on the squads to kill commuters and their competitors’ taxi scale of other quasi-military clashes between armed bosses on such a scale that they need to negotiate groups and examine other contemporary vigilante amnesty for their hit squads before they can renounce organisations in South Africa. These phenomena such illegal activities.6 peaked during the1990s as the authority of white su- 7 premacy collapsed, while state transfor- Petrol-bombing minibuses and shooting 8 mation and the construction of new drivers were routine. In Cape Town, kill- democratic authorities and institutions Quasi-military ings started in 1993 when seven drivers 9 took a good decade to be consolidated. were shot. There, the rival taxi associa- clashes tions (Cape Amalgamated Taxi Associa- The first category of such armed group- between tion, Cata, and the Cape Organisation of ings is feuding between clans (‘faction Democratic Taxi Associations, Codeta), fighting’ in settler jargon). This results in armed groups both appointed a ‘top ten’ to negotiate escalating death tolls once the rural com- peaked in the with the bus company, and a ‘bottom ten’ batants illegally buy firearms. For de- as a hit squad. The police were able to cades, feuding in Msinga1 has resulted in 1990s as the secure triple life sentences plus 70 years thousands of displaced persons. -

Ebrahim E. I. Moosa

January 2016 Ebrahim E. I. Moosa Keough School of Global Affairs Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies University of Notre Dame 100 Hesburgh Center for International Studies, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA 46556-5677 [email protected] www.ebrahimmoosa.com Education Degrees and Diplomas 1995 Ph.D, University of Cape Town Dissertation Title: The Legal Philosophy of al-Ghazali: Law, Language and Theology in al-Mustasfa 1989 M.A. University of Cape Town Thesis Title: The Application of Muslim Personal and Family Law in South Africa: Law, Ideology and Socio-Political Implications. 1983 Post-graduate diploma (Journalism) The City University London, United Kingdom 1982 B.A. (Pass) Kanpur University Kanpur, India 1981 ‘Alimiyya Degree Darul ʿUlum Nadwatul ʿUlama Lucknow, India Professional History Fall 2014 Professor of Islamic Studies University of Notre Dame Keough School for Global Affairs 1 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Department of History Co-director, Contending Modernities Previously employed at the University of Cape Town (1989-2001), Stanford University (visiting professor 1998-2001) and Duke University (2001-2014) Major Research Interests Historical Studies: law, moral philosophy, juristic theology– medieval studies, with special reference to al-Ghazali; Qur’anic exegesis and hermeneutics Muslim Intellectual Traditions of South Asia: Madrasas of India and Pakistan; intellectual trends in Deoband school Muslim Ethics medical ethics and bioethics, Muslim family law, Islam and constitutional law; modern Islamic law Critical Thought: law and identity; religion and modernity, with special attention to human rights and pluralism Minor Research Interests history of religions; sociology of knowledge; philosophy of religion Publications Monographs Published Books What is a Madrasa? University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015): 290. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

Investigation Into NMT Facilities in South Africa

CENTRE FOR TRANSPORT STUDIES MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING SPECIALISING IN CIVIL ENGINEERING Investigation into the Effects of Non-Motorised Transport Facility Implementations and Upgrades in Urban South Africa MAJOR DISSERTATION (CIV5000Z) University of Cape Town PREPARED FOR: A/PROF MARIANNE VANDERSCHUREN PREPARED BY: JENNIFER L BAUFELDT (BFLJEN001) The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the Southern Transportation Centre of Development for their financial support of this Masters. A great thank you to Prof Vanderschuren, my supervisor, for always being available, supportive and enthusiastic about my work, as well as including me in various events and projects that helped me to grow both personally and professionally. Furthermore, I would like to thank the City of Cape Town’s NMT division and Transport for Cape Town, especially Teuns Kok and his team, who both have been most forthcoming with information and data. I would like to thank the Writing Centre of the University of Cape Town for all their help, especially Liberty Eaton, who had a major role in reviewing and adding valuable comments on all sections of the work. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends, Scott Badenhorst and Catherine Hutchings for their valuable time and constructive feedback on multiple draft versions. -

Conference Facilities Transport & Shuttle Service Laundry and Valet 24 Hour Reception

World Class Africa Make your reservation today at Central Reservations: 086 111 5555 | www.premierhotels.co.za PREMIER HOTELS • PREMIER RESORTS • SPLENDID INNS BY PREMIER EXPRESS INNS BY PREMIER • EAST LONDON INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION CENTRE Introduction The Premier Hotel Cape Town is located in the beautifully tree-lined Marais Road on the Sea Point promenade in Cape Town, commanding spectacular views of Table Mountain or the awe inspiring Atlantic Ocean. This Western Cape hotel is in close proximity to all major tourist attractions including Table Mountain, the world famous Victoria and Alfred Waterfront, Green Point Stadium as well as the Camps Bay and Clifton beaches, thereby making it the best accommodation choice for both leisure travellers and business executives. Guests at the Premier Hotel Cape Town can enjoy wonderful evenings out in the cosmopolitan area of Cape Town and then return to their comfortable rooms with mountain & sea views for pure relaxation. Alternatively, enjoy your favourite drink on the hotel deck at the Promenade Cocktail Bar while watching the sun set over the Atlantic Ocean. Whether you are looking for a business facility, stylish accommodation, or a family self catering unit while on holiday, we at Premier Hotel Cape Town welcome you to the best of Cape hospitality. Premier Hotel Cape Town • Cape Town • Western Cape • South Africa Overview LOCATION ACCOMMODATION 85 Standard Rooms 17 Deluxe Rooms King, Queen, Double or Twin beds King beds | En-suite bathroom En-suite bathroom | Tea & coffee facilities Tea & coffee facilities | Telephone Premier Hotel Cape Town boasts spectacular views of the Atlantic Ocean, as Telephone | Flat screen TV with DSTV Flat screen TV with DSTV | Hair dryer well as Table Mountain, and is a mere 4.5km away from Cape Town CBD. -

The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J

University of Massachusetts School of Law Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts School of Law Faculty Publications 2016 The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J. Peltz-Steele University of Massachusetts School of Law - Dartmouth, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umassd.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard J. Peltz-Steele, The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between (Sept 27, 2016) (unpublished paper). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard Peltz-Steele Abstract With Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022 on the horizon, the process for selecting hosts for the World Cup of men’s football has been plagued by charges of corruption and human rights abuses. FIFA celebrated key developing economies with South Africa 2010 and Brazil 2014. But amid the aftermath of the global financial crisis, those sitings surfaced grave and persistent criticism of the social and economic efficacy of sporting mega-events. Meanwhile new norms emerged in global governance, embodied in instruments such as the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and the Sustainable Development Goals. These norms posit that commercial aims can be harmonized with socioeconomic good. FIFA seized on the chance to restore public confidence and recommit itself to human exultation in sport, adopting sustainability strategies and engaging the architect of the UNGP to develop a human rights policy. -

Heritage Statement

HERITAGE STATEMENT ERF 177552 MILL STREET NEWLANDS CAPE TOWN APPLICATION TO DEMOLISH EXISTING BUILDING SUBMITTED TO HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE IN TERMS OF NATIONAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ACT NO 25 OF 1999 SECTION 34 View of site from Campground Bridge building indicated with red arrow, Google Earth 2015 Prepared for Eris Property Group 10th Floor 80 Strand Street Cape Town 8001 E-mail: [email protected] Tel +27 21 410 1160 Fax +27 21 418 2249 PostNet Suite 122 Private Bag X1005 Claremont 7735 Cape Town South Africa Mobile: 0711090900 Fax: 086 511 0389 E-Mail: [email protected] HERITAGE STATEMENT ERF 177552 MILL STREET NEWLANDS CAPE TOWN FINAL 17 JULY 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 3 1.3 THE SITE 3 1.4 REPORT SCOPE OF WORK 3 1.5 ASSUMPTIONS AND LIMITATIONS 3 1.5.1 ASSUMPTIONS 3 1.5.2 LIMITATIONS 3 1.6 SPECIALIST TEAM AND DETAILS 3 1.7 DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 3 1.8 REPORT STRUCTURE 4 SECTION 2 STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 5 2.1 INTRODUCTION 5 2.2 ADMINISTRATIVE CONTEXT AND STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 5 2.2.1 INTRODUCTION 5 2.2.2 NATIONAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ACT NO. 25 OF 1999 (NHR ACT) 5 2.2.3 MUNICIPAL POLICY AND PLANNING CONTEXT 6 SECTION 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE AND CONTEXT 9 3.1 NEWLANDS DEVELOPMENT 9 3.2 CONTEXTUAL ASSESSMENT OF SITE 11 3.3 DEVELOPMENT OF SITE 12 3.4 CONTEXT 16 3.5 SITE 18 SECTION 4 SITE & CONTEXT IDENTIFIED HERITAGE RESOURCES & STATEMENT OF HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCES 20 4.1 INTRODUCTION 20 4.2 SITE AND CONTEXT: PROVISIONAL STATEMENT OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 20 SECTION 5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 22 5.1 CONCLUSION 22 5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS 22 5.3 SOURCES 22 BRIDGET O’DONOGHUE ARCHITECT, HERITAGE SPECIALIST ENVIRONMENT 2 SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION Tommy Brummer Town Planners on behalf of their client, Eris Property Group appointed Bridget O’Donoghue Architect, Heritage Specialist, Environment for a Heritage Statement for the proposed demolition of the existing building situated on Erf 177552 Newlands Cape Town. -

CBB Cape Town Students Find Inspiration in a Nation in Flux

Colby Magazine Volume 91 Issue 1 Winter 2002 Article 8 January 2002 A Brave New World: CBB Cape Town students find inspiration in a nation in flux Gerry Boyle Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Part of the African Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boyle, Gerry (2002) "A Brave New World: CBB Cape Town students find inspiration in a nation in flux," Colby Magazine: Vol. 91 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol91/iss1/8 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. CBB Cape Town students find inspiration in a nation in flux By Gerry Boyle 778 • Photos by Irvine Clements ; ou spend days interviewing, observing, scribbling in notebooks, ing squatter settlements. It carries with it still an abhorrent racist holding up a tape recorder. Later you pore over notebooks and legacy, yet African-American students who hive been to Cape tapes,Y sift the wheat from the journalistic chaff, search for that one To wn talk of fi nding for the fi rst time escape from the subtle moment, that single situation, that pearl-like utterance that captures racism of America. precisely the spirit of the subject, the place, the story. Cape To wn is a place where unquenchable optimism springs from Ifyou're writing about Cape To wn and the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin the violence and poverty of the racially segregated townships like program based in the city, there are too many choices. -

P19 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20, 2016 SPORTS Infantino eyes regional World Cup if elected FIFA president LONDON: The World Cup could be honor and benefits of hosting the World tions will be handed $40 million to invest has to be an objective assessment based spread across entire regions, emulating Cup,” Infantino’s manifesto says. in development projects and their on the best interests of football.” the continent-wide 2020 European The first World Cup bidding after the regional offshoots in Asia, Africa, the The International Football Association Championship, if Gianni Infantino wins Feb. 26 election is for the 2026 tourna- Caribbean and Central America can Board is already preparing to approve tri- next month’s FIFA presidential election. ment. The launch of the contest has been request another $4 million to organize als with a type of video replay system for The UEFA secretary general used his stalled since last year when FIFA was youth tournaments. The amounts are all referees. One idea Infantino proposes, manifesto, which was published Tuesday, swept up in a global soccer corruption within a four-year cycle. “If the target of which seems unique in an election cam- to say FIFA should not limit the tourna- scandal, which led to Sepp Blatter 50 percent of distribution of FIFA’s paign with few differences between the ment to be being held in one or two announcing plans to quit before being income is reached, these amounts will candidates, is starting a globe-trotting countries. The 2002 World Cup in Japan banned. Infantino, who is Swiss, is one of further increase significantly,” Infantino team of the game’s greats. -

Global Media Sport: Flows, Forms and Futures

Rowe, David. "Tactical Manoeuvres, Public Relations Disasters and the Global Sport Scandal." Global Media Sport: Flows, Forms and Futures. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. 115–143. Globalizing Sport Studies. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849661577.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 23:48 UTC. Copyright © David Rowe 2011. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Tactical Manoeuvres, Public Relations Disasters and the Global Sport Scandal Publicity: the good, the bad and the spaces between Sport, from its inception in modernity, has been intimately connected to international relations and trade. It has been especially effective in this regard because, despite being suffused with politics and signifi cantly commodifi ed, sport somehow still manages to present itself and to be seen by many as somehow above and beyond the mundane world of political and economic conduct. Developing international relationships through sport – so-called sport diplomacy – is viewed as a reasonably safe, benign way of making friends and managing confl icts (Levermore and Budd 2004). There are several historical examples, ranging from the so-called ping-pong diplomacy that brought the United States and Communist China into contact in the early 1970s (Xu 2008) to the attempted use of the Olympics to improve relations between North and South Korea (Merkel 2008). When, for example, in 2006 Australia left the Oceania Football Confederation for the larger Asian Football Confederation, the non-sporting justifi cation was that of ‘football diplomacy’: Sport … provides a common point of conversation between societies. -

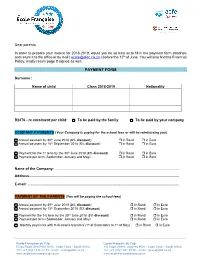

Payment Form Attached and Return It to the Office Or by Mail ( [email protected] ) Before the 12Th of June

Dear parents, In order to prepare your invoice for 2018-2019, would you be so kind as to fill in the payment form attached and return it to the office or by mail ( [email protected] ) before the 12th of June. You will also find the Financial Policy, kindly return page 8 signed as well. PAYMENT FORM Surname : Name of child Class 2018-2019 Nationality R2376 - re enrolment per child: To be paid by the family To be paid by your company COMPANY PAYMENTS (Your Company is paying for the school fees or will be reimbursing you) Annual payment by 30th June 2018 (8% discount) in Rand in Euro Annual payment by 15th September 2018 (5% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment for the 1st term by the 30th June 2018 (3% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment per term (September, January and May) in Rand in Euro Name of the Company: ............................................................................................................................ Address...................................................................................................................................................... E-mail: ....................................................................................................................................................... PAYMENT BY THE PARENTS (You will be paying the school fees) Annual payment by 30th June 2018 (8% discount) in Rand in Euro Annual payment by 15th September 2018 (5% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment for the 1st term by the 30th June 2018 (3% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment per