Uzbekistan's Implementation of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report

U.S. Commission on InternationalUSCIRF Religious Freedom Annual Report 2012 Front Cover: Nearly 3,000 Egyptian mourners gather in central Cairo on October 13, 2011 in honor of Coptic Christians among 25 people killed in clashes during a demonstration over an attack on a church. MAHMUD HAMS/AFP/Getty Images Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Commissioners Leonard A. Leo Chair Dr. Don Argue Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Vice Chairs Felice D. Gaer Dr. Azizah al-Hibri Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. William J. Shaw Nina Shea Ted Van Der Meid Ambassador Suzan D. Johnson Cook, ex officio, non-voting member Ambassador Jackie Wolcott Executive Director Professional Staff David Dettoni, Director of Operations and Outreach Judith E. Golub, Director of Government Relations Paul Liben, Executive Writer John G. Malcolm, General Counsel Knox Thames, Director of Policy and Research Dwight Bashir, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Scott Flipse, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Sahar Chaudhry, Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Jacqueline A. Mitchell, Executive Coordinator U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 790 Washington, DC 20002 202-523-3240, 202-523-5020 (fax) www.uscirf.gov Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Table of Contents Overview of Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………..1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1 Countries of Particular Concern and the Watch List…………………………………2 Overview of CPC Recommendations and Watch List……………………………….6 Prisoners……………………………………………………………………………..12 USCIRF’s Role in IRFA Implementation…………………………………………………14 Selected Accomplishments…………………………………………………………..15 Engaging the U.S. -

A Comparative Essay on the Last Years of Islam Karimov's Reign And

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1427-9657.08.11 EASTERN REVIEW 2019, T. 8 Krystian Pachucki-Włosek https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4527-5441 Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland Faculty of International Studies and Political Studies Institute for Russian and Eastern European Studies UJ e-mail: [email protected] Old and New Uzbekistan – A comparative essay on the last years of Islam Karimov’s reign and Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s presidency Abstract. The article aims to present the positive and negative effects ofthe change in the position of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan. The article focuses on economic issues, comparing the policy of President Islam Karimov and the policy of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev. The work also compares the foreign policy of both leaders towards Uzbekistan’s largest political partners: Russia and China. The above article tries to answer the question: are the changes in Uzbekistan ignificants after 2016 or only superficial? Keywords: Republic of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, internal policy, foreign policy. Introduction For many years, Uzbekistan was mainly associated with a dictatorial president. A number of wealthy states have wanted to expand their businesses in the excavation industry there, with varying results. There have been a lot of obstacles to this, as proved by the international indexes. In terms of economic freedom, Uzbekistan received 87th place in 2016 (Gazeta.uz., 2015). When we inspect further, the country was given 156th place in a corruption index as well as 166th place in an economic freedom index (Heritage.org., 2019). The situation © by the author, licensee Łódź University – Łódź University Press, Łódź, Poland. -

Could Uzbekistan Lead Central Asia?

Could Uzbekistan Lead Central Asia? In surprise move, previously isolated state calls for tighter regional integration. Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev. (Photo: Uzbek president’s press service) Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev has called for closer cooperation between all five countries of Central Asia in a move which some believe signals a new and more vigorous regional role for Tashkent. At an international conference on the Central Asia’s future, held in the historic Uzbek city of Samarkand in early November, Mirziyoyev emphasised that he supported efforts to create “a stable, economically developed and thriving region”. “I am sure that all will win from this – both the Central Asian states and other countries,” Mirziyoyev told the event, held under the auspices of the UN and attended by senior officials, diplomats and experts from the region, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and further afield. The event itself and Mirziyoyev’s address were both unusual. Initial attempts at regional unity following the fall of the Soviet Union were short-lived. For more than a decade the five states have not seriously discussed cooperating on domestic development and remain embroiled in disputes over water resources, borders and market protectionism amid general mistrust between the leadership. In fact, it was Uzbekistan, under the rule of former president Islam Karimov, which was the most sceptical about regional cooperation. As the successor to Karimov, who died in September 2016, Mirziyoyev has taken a number of measures that appear to show willingness to open up one of the world’s most isolated states. (See Could Uzbekistan be Opening Up?). -

Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests

Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs August 12, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21238 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary Uzbekistan is a potential Central Asian regional power by virtue of its relatively large population, energy and other resources, and location in the heart of the region. However, it has failed to make progress in economic and political reforms, and many observers criticize its human rights record. This report discusses U.S. policy and assistance and basic facts and biographical information are provided. Related products include CRS Report RL33458, Central Asia: Regional Developments and Implications for U.S. Interests, by Jim Nichol. Congressional Research Service Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Contents U.S. Relations.............................................................................................................................1 Contributions to Counter-Terrorism.............................................................................................3 Foreign Policy and Defense.........................................................................................................4 Political and Economic Developments ........................................................................................7 Figures Figure 1. Map of Uzbekistan .......................................................................................................2 -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

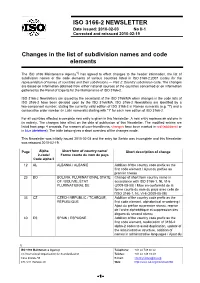

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S

Order Code RS21238 Updated May 2, 2005 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Uzbekistan is an emerging Central Asian regional power by virtue of its relatively large population, energy and other resources, and location in the heart of the region. It has made limited progress in economic and political reforms, and many observers criticize its human rights record. This report discusses U.S. policy and assistance. Basic facts and biographical information are provided. This report may be updated. Related products include CRS Issue Brief IB93108, Central Asia, updated regularly. U.S. Policy1 According to the Administration, Uzbekistan is a “key strategic partner” in the Global War on Terrorism and “one of the most influential countries in Central Asia.” However, Uzbekistan’s poor record on human rights, democracy, and religious freedom complicates its relations with the United States. U.S. assistance to Uzbekistan seeks to enhance the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and security of Uzbekistan; diminish the appeal of extremism by strengthening civil society and urging respect for human rights; bolster the development of natural resources such as oil; and address humanitarian needs (State Department, Congressional Presentation for Foreign Operations for FY2006). Because of its location and power potential, some U.S. policymakers argue that Uzbekistan should receive the most U.S. attention in the region. 1 Sources for this report include the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS), Central Eurasia: Daily Report; Eurasia Insight; RFE/RL Central Asia Report; the State Department’s Washington File; and Reuters, Associated Press (AP), and other newswires. -

CORI Country Report Uzbekistan, November 2010

CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Uzbekistan, November 2010 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by Uzbekistan nationals. This report covers events up to 30 November 2010. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

Download This Report

Human Rights Watch September 2005 Vol. 17, No. 6(D) Burying the Truth Uzbekistan Rewrites the Story of the Andijan Massacre Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology and a Note on the Use of Pseudonyms ............................................................ 7 Background .................................................................................................................................... 7 The Andijan Uprising, Protests, and Massacre..................................................................... 7 Early Post-massacre Cover-up and Intimidation of Witnesses ......................................... 9 The Criminal Investigation into the Andijan Events ........................................................ 10 Uzbek Media Coverage of the Andijan Events.................................................................. 13 Coercive Pressure for Testimony .............................................................................................14 Detention and Abuse in Andijan.......................................................................................... 16 Initial Detention...................................................................................................................... 17 Interrogations .......................................................................................................................... 18 Misdemeanor Hearings and Detention............................................................................... -

Languages, Countries and Codes (LCCTM)

Date: September 2017 OBJECT MANAGEMENT GROUP Languages, Countries and Codes (LCCTM) Version 1.0 – Beta 2 _______________________________________________ OMG Document Number: ptc/2017-09-04 Standard document URL: http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/1.0/ Normative Machine Consumable File(s): http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/CountryRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/20170801/Countries/CountryRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ UN-M49-RegionCodes .rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ UN-M49-Region Codes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/CountryRepresentation.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ UN-M49-Region Codes. -

Oecd Development Centre

OECD DEVELOPMENT CENTRE Working Paper No. 212 (Formerly Technical Paper No. 212) CENTRAL ASIA SINCE 1991: THE EXPERIENCE OF THE NEW INDEPENDENT STATES by Richard Pomfret Research programme on: Market Access, Capacity Building and Competitiveness July 2003 DEV/DOC(2003)10 DEV/DOC(2003)10 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .........................................................................................................................5 RÉSUMÉ...........................................................................................................................6 SUMMARY........................................................................................................................7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................8 I. INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................11 II. BACKGROUND...........................................................................................................12 III. MACROECONOMIC PERFORMANCE DURING THE FIRST DECADE AFTER INDEPENDENCE ..........................................................................................14 IV. EXPLAINING PERFORMANCE: INITIAL CONDITIONS VERSUS NATIONAL POLICIES................................................................................................17 V. WINNERS AND LOSERS: EVIDENCE FROM HOUSEHOLD SURVEYS .................25 VI. INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICIES: REGIONALISM AND INTEGRATION INTO THE WORLD ECONOMY.................................................................................35 -

Republic of Uzbekistan

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 27 December 2009 OSCE/ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Final Report Warsaw 7 April 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................... 2 III. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT....................................................................... 3 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK.......................................................................................................................... 5 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION .......................................................................................................... 8 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION AND VOTER LISTS ................................................................................. 9 VII. CANDIDATE NOMINATION AND REGISTRATION......................................................................10 VIII. ELECTION CAMPAIGN .......................................................................................................................12 IX. MEDIA......................................................................................................................................................13 A. MEDIA ENVIRONMENT ..........................................................................................................................13 B. LEGAL