Uzbekistan: Welfare Impact of Slow Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report

U.S. Commission on InternationalUSCIRF Religious Freedom Annual Report 2012 Front Cover: Nearly 3,000 Egyptian mourners gather in central Cairo on October 13, 2011 in honor of Coptic Christians among 25 people killed in clashes during a demonstration over an attack on a church. MAHMUD HAMS/AFP/Getty Images Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Commissioners Leonard A. Leo Chair Dr. Don Argue Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Vice Chairs Felice D. Gaer Dr. Azizah al-Hibri Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. William J. Shaw Nina Shea Ted Van Der Meid Ambassador Suzan D. Johnson Cook, ex officio, non-voting member Ambassador Jackie Wolcott Executive Director Professional Staff David Dettoni, Director of Operations and Outreach Judith E. Golub, Director of Government Relations Paul Liben, Executive Writer John G. Malcolm, General Counsel Knox Thames, Director of Policy and Research Dwight Bashir, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Scott Flipse, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Sahar Chaudhry, Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Jacqueline A. Mitchell, Executive Coordinator U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 790 Washington, DC 20002 202-523-3240, 202-523-5020 (fax) www.uscirf.gov Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Table of Contents Overview of Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………..1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1 Countries of Particular Concern and the Watch List…………………………………2 Overview of CPC Recommendations and Watch List……………………………….6 Prisoners……………………………………………………………………………..12 USCIRF’s Role in IRFA Implementation…………………………………………………14 Selected Accomplishments…………………………………………………………..15 Engaging the U.S. -

Burgernomics: a Big Mac Guide to Purchasing Power Parity

Burgernomics: A Big Mac™ Guide to Purchasing Power Parity Michael R. Pakko and Patricia S. Pollard ne of the foundations of international The attractive feature of the Big Mac as an indi- economics is the theory of purchasing cator of PPP is its uniform composition. With few power parity (PPP), which states that price exceptions, the component ingredients of the Big O Mac are the same everywhere around the globe. levels in any two countries should be identical after converting prices into a common currency. As a (See the boxed insert, “Two All Chicken Patties?”) theoretical proposition, PPP has long served as the For that reason, the Big Mac serves as a convenient basis for theories of international price determina- market basket of goods through which the purchas- tion and the conditions under which international ing power of different currencies can be compared. markets adjust to attain long-term equilibrium. As As with broader measures, however, the Big Mac an empirical matter, however, PPP has been a more standard often fails to meet the demanding tests of elusive concept. PPP. In this article, we review the fundamental theory Applications and empirical tests of PPP often of PPP and describe some of the reasons why it refer to a broad “market basket” of goods that is might not be expected to hold as a practical matter. intended to be representative of consumer spending Throughout, we use the Big Mac data as an illustra- patterns. For example, a data set known as the Penn tive example. In the process, we also demonstrate World Tables (PWT) constructs measures of PPP for the value of the Big Mac sandwich as a palatable countries around the world using benchmark sur- measure of PPP. -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Math Calculations to Better Utilize CPI Data

Math calculations to better utilize CPI data Report prepared by Gerald Perrins, branch chief of Consumer Prices in the Mid-Atlantic region, and Diane Nilsen, former regional clearance officer in the National Office of Field Operations, Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is published points, because index point changes are as an index number that shows the change in affected by the level of the index in relation to the price of a defined market basket of goods its base period, while percent changes are not. and services over time from a base period which is defined as 100.0. An increase of 7 The following illustration shows a percent from that base period, for example, is hypothetical CPI one-month change between shown as 107.0. Alternately, that relationship April 2016 and May 2016 using the 1982- can also be expressed as the price of a base 84=100 reference base. period "market basket" of goods and services rising from $100 to $107. Currently, the Reference Base reference base for most CPI indexes is 1982- 1982-84=100 84=100 but some indexes have other May 2016 ........................................ 240.236 references bases. The reference base years April 2016 ....................................... 239.261 refer to the period in which the index is set to Index point change .............................. 0.975 100.0. In addition, expenditure weights are Divided by the earlier index ..... 0.975/239.261 updated every two years to keep the CPI Equals ............................................... 0.004075 current with changing consumer preferences. Multiplied by 100 ............................... 0.4075 Equals percent change ........................ 0.4 Index numbers are not dollar values, but measures of the change over time relative to Over-the-year percent change their base period value of 100.0 (for example, To arrive at a percent change over an entire 280.0 or 30.3). -

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP)

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP): The sum of all spending from four sectors of the economy. GDP = C+I+G+Xn 2. Aggregate Income (AI) :The sum of all income earned by suppliers of resources in the economy. AI=GDP 3. Nominal GDP: the value of current production at the current prices 4. Real GDP: the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time 5. Base year: the year that serves as a reference point for constructing a price index and comparing real values over time. 6. Price index: a measure of the average level of prices in a market basket for a given year, when compared to the prices in a reference (or base) year. 7. Market Basket: a collection of goods and services used to represent what is consumed in the economy 8. GDP price deflator: the price index that measures the average price level of the goods and services that make up GDP. 9. Real rate of interest: the percentage increase in purchasing power that a borrower pays a lender. 10. Expected (anticipated) inflation: the inflation expected in a future time period. This expected inflation is added to the real interest rate to compensate for lost purchasing power. 11. Nominal rate of interest: the percentage increase in money that the borrower pays the lender and is equal to the real rate plus the expected inflation. 12. Business cycle: the periodic rise and fall (in four phases) of economic activity 13. Expansion: a period where real GDP is growing. 14. Peak: the top of a business cycle where an expansion has ended. -

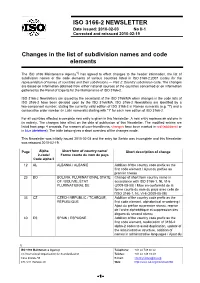

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Using Price Indexes

INFORMATION BRIEF Research Department Minnesota House of Representatives 600 State Office Building St. Paul, MN 55155 Pat Dalton, Legislative Analyst, 651-296-7434 Kathy Novak, Legislative Analyst, 651-296-9253 Updated: November 2009 Using Price Indexes This information brief is a nontechnical guide to the use of price indexes. It explains the difference among the three most commonly used price indexes and suggests when each index should be used. Additionally, this information brief shows how to make some common calculations using price indexes. Contents Price Indexes and Their Uses ...........................................................................................................2 Descriptions of the Major Price Indexes ..........................................................................................2 Gross Domestic Product Chain-Weighted Price Index ..............................................................2 Consumer Price Index (CPI) ......................................................................................................4 Producer Price Index (PPI) ........................................................................................................5 Glossary of Price Index Terms ........................................................................................................7 Common Calculations Using Price Indexes ....................................................................................8 Summary of Major Price Indexes ..................................................................................................10 -

The Market Basket Powerpoint Lesson Plan

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS ECONOMIC EDUCATION The Market Basket PowerPoint Lesson Plan Lesson Author Jeannette Bennett, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis —Memphis Branch Standards and Benchmarks (see page 12) Lesson Description In this lesson, students will compare the price of goods from one time period to another and through discussion and role play interpret the effects of inflation on con - sumers. They will categorize goods and services according to the eight major groups of the consumer price index (CPI) and be able to determine the difference between the CPI and the core CPI. Grade Level 9-12 Time Required 60-90 minutes Concepts Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer price index (CPI) Core CPI Goods Inflation Inflation rate Purchasing power Services ©2013, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Permission is granted to reprint or photocopy this lesson in its entirety for educational purposes, provided the user credits the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, www.stlouisfed.org/education_resources. 1 PowerPoint Lesson Plan The Market Basket Objectives Students will • define inflation, inflation rate, consumer price index (CPI), and core CPI; • explain how inflation affects purchasing power; • determine the price of goods and services from one year to another as adjusted for inflation by using an online calculator; • identify the categories of consumer spending included in the CPI and the core CPI; and • explain a role of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Materials • PowerPoint presentation “The Market Basket” • Handout 1, one copy cut apart, making eight strips • Handout 2, one copy for each student • Handout 3, one copy for each student • One first-class postage stamp to use as a visual • Internet access Procedure 1. -

Download This Report

Human Rights Watch September 2005 Vol. 17, No. 6(D) Burying the Truth Uzbekistan Rewrites the Story of the Andijan Massacre Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology and a Note on the Use of Pseudonyms ............................................................ 7 Background .................................................................................................................................... 7 The Andijan Uprising, Protests, and Massacre..................................................................... 7 Early Post-massacre Cover-up and Intimidation of Witnesses ......................................... 9 The Criminal Investigation into the Andijan Events ........................................................ 10 Uzbek Media Coverage of the Andijan Events.................................................................. 13 Coercive Pressure for Testimony .............................................................................................14 Detention and Abuse in Andijan.......................................................................................... 16 Initial Detention...................................................................................................................... 17 Interrogations .......................................................................................................................... 18 Misdemeanor Hearings and Detention............................................................................... -

Facts About the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The four surveys used in the Effects of the CPI Facts construction of the CPI The CPI can be used to measure and compare about the Telephone Point-of-Purchase Survey consumers’ purchasing power in different time (TPOPS) — This household survey, conducted periods. As prices increase, the purchasing Consumer by the U.S. Census Bureau for BLS, provides the power of a consumer’s dollar declines, and as sampling frame for the Commodities and Services prices decrease, the consumer’s purchasing Price Index Pricing Survey. Roughly 30,000 households are power increases. (CPI) interviewed each year and asked to identify the The CPI is often used to adjust consumers’ “points” at which they purchase consumer items. income payments. For example, the CPI is This gives BLS a list of grocery stores, department used to adjust Social Security benefits, to adjust stores, doctor’s offices, theaters, internet sites, income eligibility levels for government assistance, shopping malls, etc., currently patronized by urban and to automatically provide cost-of-living wage consumers. adjustments to millions of American workers. Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) — This household survey, conducted by the U.S. Census The CPI affects more than 100 million persons Bureau for BLS, provides information on the as a result of statutory action: buying habits of American consumers. More than 7,000 families from around the country Over 50 million Social Security beneficiaries provide information each calendar quarter on their About 20 million food stamp recipients in the spending habits in the Quarterly Interview Survey, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and another 7,000 families complete expense diaries (SNAP) in the Diary Survey each year. -

New Basket of Goods and Services Being Priced in Revised

New basket of goods and services being priced in revised CPI Beginning with January 1987 estimates, the Consumer Price Index reflects changes in Americans' spending patterns since 1972-73 ; the new index permits more accurate tracking of price changes throughout the 1980's CHARLES MASON AND CLIFFORD BUTLER The Consumer Price Index (cPi) is being revised effective Construction of the market basket with publication of data for January 1987 .' As a part of the The Consumer Price Index is a measure of the average revision, the market basket of goods and services priced for change in the price paid by urban consumers for a fixed the index is being updated to reflect how consumers are market basket of goods and services .2 The composition and spending their money. Buying patterns can change over relative weight of each component of that market basket is time as a result of changes in prices, demographic character- derived from estimates of expenditures from the ongoing istics of the population, income, or tastes and habits. Histor- Consumer Expenditure Survey. 3 The expenditure data are ically, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has updated the cps tabulated using a hierarchical system with three principal market basket approximately every 10 years. The uses of the levels of aggregation. cpi as a measure of inflation and the effects of economic The seven major expenditure groups-food and bever- policy, as a deflator of other statistical series, and as an ages, housing, apparel and upkeep, transportation, medical income or benefits escalator require that it be current and care, entertainment, and other goods and services-are dis- accurate . -

Languages, Countries and Codes (LCCTM)

Date: September 2017 OBJECT MANAGEMENT GROUP Languages, Countries and Codes (LCCTM) Version 1.0 – Beta 2 _______________________________________________ OMG Document Number: ptc/2017-09-04 Standard document URL: http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/1.0/ Normative Machine Consumable File(s): http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/CountryRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/20170801/Countries/CountryRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ UN-M49-RegionCodes .rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ UN-M49-Region Codes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/CountryRepresentation.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ UN-M49-Region Codes.