Jti-2020-0020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Pharmtech Research CODEN (USA): IJPRIF, ISSN: 0974-4304, ISSN(Online): 2455-9563 Vol.13, No.01, Pp 20-25, 2020

International Journal of PharmTech Research CODEN (USA): IJPRIF, ISSN: 0974-4304, ISSN(Online): 2455-9563 Vol.13, No.01, pp 20-25, 2020 Comparison of Post-Operative Clinical Outcome of Patients with PosteriorInstrumentation After Spinal Cord Injury in Thoracic, Thoracolumbar, and Lumbar Region at Haji Adam Malik General Hospital, Medan from 2016 to 2018 Budi Achmad M. Siregar1*, Pranajaya Dharma Kadar2, Aga Shahri Putera Ketaren3 1Resident of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sumatera Utara / Haji Adam Malik General Hospital, Medan, Indonesia 2Consultant Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Spine Division, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sumatera Utara / Haji Adam Malik General Hospital, Medan, Indonesia 3Consultant Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Upper Extremity Division,Faculty of Medicine, University of Sumatera Utara / Haji Adam MalikGeneral Hospital, Medan , Indonesia Abstract : Introduction : Spinal cord injury is a damaging situation related to severe disability and death after trauma.And the term spinal cord injury refers to damage of the spinal cord resulting from trauma. Spinal injuries treatment is still in debate for some cases, whether using conservative or surgical methods. Material and Methods : The study was a retrospective, unpaired observational analytic study with a cross- sectional approach. It was conducted at Haji Adam Malik General Hospital, Medan from January 2016 to December 2018. Clinical outcome of patientswere calculated using SF 36, ODI, and VAS.Data would be tested using the Saphiro-Wilk test. We were using the significance level of 1% (0.01) and the relative significance level of 10% (0.1). Results : Clinical outcomes of patients with spinal cord injuries before posterior instrumentation rated using ODI and VAS were 75.93±6.75 and 4.75±0.98 respectively. -

Missed Spinal Lesions in Traumatized Patients Ana M Cerván De La Haba*, Miguel Rodríguez Solera J, Miguel S Hirschfeld León and Enrique Guerado Parra

de la Haba et al. Trauma Cases Rev 2016, 2:027 Volume 2 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2469-5777 Trauma Cases and Reviews Case Series: Open Access Missed Spinal Lesions in Traumatized Patients Ana M Cerván de la Haba*, Miguel Rodríguez Solera J, Miguel S Hirschfeld León and Enrique Guerado Parra Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Traumatology and Rehabilitation, Hospital Universitario Costa del Sol. University of Malaga, Spain *Corresponding author: Ana M Cerván de la Haba, Hospital Universitario Costa del Sol, Autovía A7 km 187 C.P. 29603, Marbella, Spain, Tel: 951976224, E-mail: [email protected] will help in decreasing the number of missed spinal injuries, being Abstract claim that standardized tertiary trauma survey is vitally important Overlooked spinal injuries and delayed diagnosis are still common in the detection of clinically significant missed injuries and should in traumatized patients. The management of trauma patients is one be included in trauma care, our misdiagnosis occurs at first or later of the most important challenges for the specialist in trauma. Proper examinations [3]. However despite even a third survey still many training and early suspicion of this lesion are of overwhelming injuries are overlooked [4,5]. importance. The damage control orthopaedics, diagnosis and treatment In this paper based on the case method, we discuss the diagnosis algorithm applied to multitrauma patients reduces both morbidity of missable spinal fractures within several traumatic settings. and mortality in polytrauma patients due to missed lesions. Algorithm on its diagnosis and after on its treatment is necessary Case Studies in order to decrease complications. Despite application of care protocols for trauma patients still exist missed spinal injuries. -

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

The Athlete's Concussion Epidemic

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Theses Theses & Dissertations Spring 5-2020 The Athlete’s Concussion Epidemic Andrew James Marsh Lindenwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Marsh, Andrew James, "The Athlete’s Concussion Epidemic" (2020). Theses. 17. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/theses/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses & Dissertations at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !1 THE ATHLETE’S CONCUSSION EPIDEMIC by Andrew Marsh Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Mass Communication at Lindenwood University © May 2020, Andrew James Marsh The author hereby grants Lindenwood University permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic thesis copies of document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. !2 THE ATHLETE’S CONCUSSION EPIDEMIC A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Broadcast and Media Operations for the School of Arts, Media, and Communications Department in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Lindenwood University By Andrew James Marsh Saint Charles, Missouri May 2020 !3 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: The Athlete’s Concussion Epidemic Andrew Marsh, Master of Arts/Mass Communication, 2020 Thesis Directed by: Mike Wall, Director of Broadcast and Media Operations for the School of Arts, Media, and Communications The main goal of this project is to inform and educate you on the various threads concerning concussions in the world of sports. -

International Association of Dental Traumatology Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 3

ENDORSEMENTS: INJURIES IN PRIMARY DENTITION International Association of Dental Traumatology Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 3. Injuries in the Primary Dentition Endorsed by the American Academy + How to Cite: Day PF, Flores MT, O’Connell AC, et al. International of Pediatric Dentistry Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 3. Injuries in the primary dentition. 2020 Dent Traumatol 2020;36:343-359. https://doi.org/10.1111/edt.12576. Authors Peter F. Day1 • Marie Therese Flores2 • Anne C. O’Connell3 • Paul V. Abbott4 • Georgios Tsilingaridis5,6 Ashraf F. Fouad7 • Nestor Cohenca8 • Eva Lauridsen9 • Cecilia Bourguignon10 • Lamar Hicks11 • Jens Ove Andreasen12 • Zafer C. Cehreli13 • Stephen Harlamb14 • Bill Kahler15 • Adeleke Oginni16 • Marc Semper17 • Liran Levin18 Abstract Traumatic injuries to the primary dentition present special problems that often require far different management when compared to that used for the permanent dentition. The International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) has developed these Guidelines as a con- sensus statement after a comprehensive review of the dental literature and working group discussions. Experienced researchers and clinicians from various specialties and the general dentistry community were included in the working group. In cases where the published data did not appear conclusive, recommendations were based on the consensus opinions or majority decisions of the working group. They were then reviewed and approved by the members of the IADT Board of Directors. The primary goal of these Guidelines is to provide clinicians with an approach for the immediate or urgent care of primary teeth injuries based on the best evidence provided by the literature and expert opinions. -

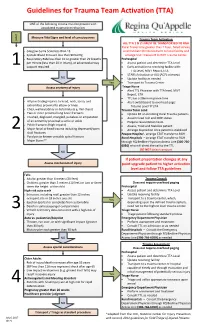

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

Chinese Expert Consensus on Echelons Treatment of Thoracic

Zong et al. Military Medical Research (2018) 5:34 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0181-6 POSITION ARTICLE AND GUIDELINES Open Access Chinese expert consensus on echelons treatment of thoracic injury in modern warfare Zhao-Wen Zong1*, Zhi-Nong Wang2, Si-Xu Chen1, Hao Qin1, Lian-Yang Zhang3, Yue Shen3, Lei Yang1, Wen-Qiong Du1, Can Chen1, Xin Zhong1, Lin Zhang4, Jiang-Tao Huo4, Li-Ping Kuai5, Li-Xin Shu6, Guo-Fu Du5, Yu-Feng Zhao3 and Representing the Traumatology Branch of the China Medical Rescue Association, the Youth Committee on Traumatology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association, the PLA Professional Committee and the Youth Committee on Disaster Medicine, and the Disaster Medicine Branch of the Chongqing Association of Integrative Medicine Abstract The emergency treatment of thoracic injuries varies of general conditions and modern warfare. However, there are no unified battlefield treatment guidelines for thoracic injuries in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA). An expert consensus has been reached based on the epidemiology of thoracic injuries and the concept of battlefield treatment combined with the existing levels of military medical care in modern warfare. Since there are no differences in the specialized treatment for thoracic injuries between general conditions and modern warfare, first aid, emergency treatment, and early treatment of thoracic injuries are introduced separately in three levels in this consensus. At Level I facilities, tension pneumothorax and open pneumothorax are recommended for initial assessment during the first aid stage. Re-evaluation and further treatment for hemothorax, flail chest, and pericardial tamponade are recommended at Level II facilities. -

The European Perspective on the Management of Acute Major Hemorrhage and Coagulopathy After Trauma: Summary of the 2019 Updated European Guideline

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article The European Perspective on the Management of Acute Major Hemorrhage and Coagulopathy after Trauma: Summary of the 2019 Updated European Guideline Marc Maegele Department of Traumatology and Orthopedic Surgery, Cologne-Merheim Medical Center (CMMC), Institute for Research in Operative Medicine (IFOM), University Witten-Herdecke, D-51109 Cologne, Germany; [email protected]; Tel.: +49-(0)-221-89-07-13-614; Fax: +49-(0)-221-89-07-30-85 Abstract: Non-controlled hemorrhage with accompanying trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) remains the most common cause of preventable death after multiple injury. Rapid identification followed by aggressive treatment is the key for improved outcomes. Treatment of trauma hemorrhage begins at the scene, with manual compression, the use of tourniquets and (non) commercial pelvic slings, and rapid transfer to an adequate trauma center. Upon hospital admission, coagulation monitoring and support are to be initiated immediately. Bleeding is controlled surgically following damage control principles. Modern coagulation management includes goal-oriented, individualized therapies, guided by point-of-care viscoelastic assays. Idarucizumab can be used as an antidote to the thrombin inhibitor dabigatran, andexanet alpha as an antidote to factor Xa inhibitors. This review summarizes the key recommendations of the 2019 updated European guideline on the management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma. These evidence-based recommendations may form the backbone of algorithms adapted to local logistics and infrastructure. Keywords: trauma; hemorrhage; coagulopathgy; guideline Citation: Maegele, M. The European Perspective on the Management of Acute Major Hemorrhage and Coagulopathy after Trauma: 1. Introduction Summary of the 2019 Updated Despite significant improvements in acute trauma care, uncontrolled hemorrhage European Guideline. -

Traumatic Cardiac Arrest

TRAUMATIC CARDIAC ARREST There are a number of studies that show that attempts at resuscitation of traumatic arrests are futile in certain situations. In these futile situations a patient should be considered dead and there should be no further resuscitation efforts. All traumatic pulseless non-breathers will undergo full resuscitation efforts unless: x All trauma with a significant mechanism of injury – If on the first arrival of EMS the patient is pulseless, apneic, and without other signs of life (pupil reactivity, spontaneous movement) or is asystolic, then the patient is not resuscitatable. x If the injuries are incompatible with life (e.g. Decapitation), the patient is not resuscitatable. Any patient not meeting one of the above criteria should have attempted resuscitation – Begin CPR. Follow appropriate Cardiac Arrest, PEA/Asystole protocol in addition to protocol below. If resuscitation has started but it is determined that patient has criteria where additional care is futile, terminate resuscitation if protocol criteria are met (line 10) or contact medical control to determine if resuscitation should be terminated. a. Once determination has been made that the patient is not resuscitatable, law enforcement and the local coroner/medical examiner should be contacted b. The EMS team is not required to stay until the coroner/medical examiner arrives, but should provide law enforcement with: i. Time of arrival and time resuscitation stopped, if applicable. ii. Names of medical crew (and Medical Control Physician if applicable). iii. Name of your EMS agency/department and business phone number. EMERGENCY MEDICAL RESPONDER (EMR) / EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIAN (EMT)/ ADVANCED EMT (AEMT)/ INTERMEDIATE / PARAMEDIC 1. -

Anytown Trauma Center Trauma Protocols

ANYTOWN TRAUMA CENTER TRAUMA PROTOCOLS TITLE: TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTOCOL PURPOSE: The purpose of the protocol is to establish guidelines for trauma team activation and define the members of the responding trauma team to facilitate the resuscitation and management of critical or seriously injured patients who require rapid, organized resuscitation, evaluation and stabilization to promote optimal outcomes. It also serves to provide triage guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. PROCESS: 1. TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTCOL A. The criteria for activation of the trauma team is clearly defined and posted at the Emergency Department triage desk, by the EMS communication station and in the resuscitation rooms. B. The trauma team may be activated prior to arrival based on the EMS communication and their assessment. C. The trauma surgeon, emergency medicine physician, emergency department charge nurse/ house supervisor, emergency department nurses and the Trauma Program Manager may activate the trauma team. D. The person calling the trauma activation will initiate the trauma page to group page the trauma team and will specify the MOI, BP, HR, ETA and level of activation required and age if available. E. If the trauma team members are present in the emergency department and alert is still communicated to ensure everyone is notified. F. Trauma team member notification and arrival times will be documented on the trauma flow sheet (paper or electronic). G. Trauma team members will sign-in when they arrive. H. Trauma team members will be activated for all patients who meet the following criteria: 1. Level 1 trauma activation (major): life threatening injuries and/or unstable vital signs, limb-threating or disability threatening injury 2. -

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital through the Emergency Department Test Questions 1. As the prehospital provider approaches the scene of a trauma call, they perform a. a radio transmission to the hospital b. a scene size up c. an estimate of neck size for c-collar d. an estimate of victim’s height and weight 2. Field intubation has been proven to improve outcome in a. patients with BP less than 90 mm Hg b. patients with GCS less than 9 c. patients with acute respiratory distress d. none of the above 3. A proven technique of hemorrhage control is a. Direct pressure b. Elevate above the heart c. Pressure points d. Cold application 4. Prehospital care for apparent pelvic fractures includes a. DO NOT ROCK or palpate the pelvis in the prehospital arena b. Avoid log rolling as much as possible c. Apply splint if in your area protocols d. All of the above 5. Most preventable deaths in trauma care are due to a. Delay in CPR b. Cardiac tamponade c. Airway obstruction d. Tension pneumothorax STN 2012 Electronic Library: Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions 2 6. For resuscitation to occur, there must be a. Cellular perfusion and tissue oxygenation b. Restoration of a blood pressure greater than 90mm Hg c. A hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL d. A PaO2 greater than 80 mm Hg 7. The Trauma Triad of Death is a. Hypotension, tachycardia and decreased urine output b. Infection, inadequate nutrition, DVT’s c. Hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy d. -

Traumatic Cardiac Arrest

CG002 Traumatic Cardiac Arrest 1. Key Recommendations for operational use For use by: Pre-hospital teams: Internet: Yes • Trauma patient in cardiac arrest or peri-arrest 1 Assess • Blunt vs penetrating • Consider primary event may have underlying medical cause Medical cause 2 • Follow ALS guidelines suspected Loss of vital signs 3 • Consider stopping resuscitation > 20 minutes • Commence IPPV via BVM / ETT / Supraglottic airway (LMA) Penetrating trauma • Perform bilateral open thoracostomies or bilateral needle decompression as dictated by 4 (Chest or clinician skill set (injured side first) epigastrium) • Consider resuscitative thoracotomy • Simultaneously address reversible pathology: • Hypovolaemia: - control external haemorrhage - splint pelvis and fractures - blood or fluid bolus (preferably via IV/IO above diaphragm) - blood is preferred fluid but if not available administer 250ml 0.9% saline boluses and monitor ETCO2 for response • Oxygenation: 5 Blunt trauma - IPPV via BVM / ETT / Supraglottic airway (LMA) • Tension pneumothorax: - perform bilateral open thoracostomies or bilateral needle decompression dictated by clinician skillset • Ultrasound: - should not delay completion of above interventions - may be applicable on case-by-case basis with individual clinician judgment paramount • CPR may not be effective until the reversible cause is addressed. 6 CPR • Addressing reversible causes takes priority over CPR • If ROSC achieved transport immediately to appropriate hospital 7 ROSC • Pre-alert with activation of Code Red protocol.