The Tale of Itu: Ritual Tale Structure of a in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S*U*P*E*R Consciousness Through Meditation Douglas Baker B.A

S*U*P*E*R CONSCIOUSNESS THROUGH MEDITATION DOUGLAS BAKER B.A. M.R.C.S. L.R.C.P. You ask, how can we know the Infinite? I answer, not by reason. It is the office of reason to distinguish and define. The Infinite, therefore, cannot be ranked among its objects. You can only apprehend the Infinite by a faculty superior to reason, by entering into a state in which you are your finite self no longer—in which the divine essence is communicated to you. This is ecstasy. It is the liberation of your mind from its finite consciousness. Like can only apprehend like; when you thus cease to be finite, you become one with the infinite. In the reduction of your soul to its simplest self, its divine essence, you realise this union, this identity. Plotinus: Letter to Flaccus CHAPTER 1 ANCIENT MYSTERIES Cosmic Consciousness The goal of all major esoteric traditions and of all world religions is entry into a higher kingdom of nature, into the realm of the gods. This kingdom is known as the Fifth Kingdom, and one’s awareness and experience of its world constitute what is referred to as the superconscious experience. It has been described by all those who have had this extraordinary glimpse of another world, in ecstatic terms, as a state of boundless being and bliss in which one’s individual consciousness merges with the universal consciousness, with the Godhead. It is a state of beingness and awareness that far surpasses one’s usual limited, narrow view of reality and transports one, for a brief moment, beyond the limits of time and space into another dimension. -

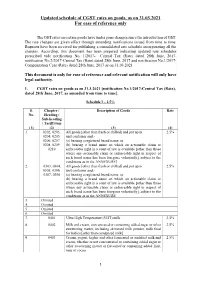

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

Non-Wood Forest Products in Asiaasia

RAPA PUBLICATION 1994/281994/28 Non-Wood Forest Products in AsiaAsia REGIONAL OFFICE FORFOR ASIAASIA AND THETHE PACIFICPACIFIC (RAPA)(RAPA) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFOF THE UNITED NATIONS BANGKOK 1994 RAPA PUBLICATION 1994/28 1994/28 Non-Wood ForestForest Products in AsiaAsia EDITORS Patrick B. Durst Ward UlrichUlrich M. KashioKashio REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIAASIA ANDAND THETHE PACIFICPACIFIC (RAPA) FOOD AND AGRICULTUREAGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFOF THETHE UNITED NTIONSNTIONS BANGKOK 19941994 The designationsdesignations andand the presentationpresentation ofof material in thisthis publication dodo not implyimply thethe expressionexpression ofof anyany opinionopinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country,country, territory, citycity or areaarea oror ofof its its authorities,authorities, oror concerningconcerning thethe delimitation of its frontiersfrontiers oror boundaries.boundaries. The opinionsopinions expressed in this publicationpublication are those of thethe authors alone and do not implyimply any opinionopinion whatsoever on the part ofof FAO.FAO. COVER PHOTO CREDIT: Mr. K. J. JosephJoseph PHOTO CREDITS:CREDITS: Pages 8,8, 17,72,80:17, 72, 80: Mr.Mr. MohammadMohammad Iqbal SialSial Page 18: Mr. A.L. Rao Pages 54, 65, 116, 126: Mr.Mr. Urbito OndeoOncleo Pages 95, 148, 160: Mr.Mr. Michael Jensen Page 122: Mr.Mr. K. J. JosephJoseph EDITED BY:BY: Mr. Patrick B. Durst Mr. WardWard UlrichUlrich Mr. M. KashioKashio TYPE SETTINGSETTING AND LAYOUT OF PUBLICATION: Helene Praneet Guna-TilakaGuna-Tilaka FOR COPIESCOPIES WRITE TO:TO: FAO Regional Office for Asia and the PacificPacific 39 Phra AtitAtit RoadRoad Bangkok 1020010200 FOREWORD Non-wood forest productsproducts (NWFPs)(NWFPs) havehave beenbeen vitallyvitally importantimportant toto forest-dwellersforest-dwellers andand rural communitiescommunities forfor centuries.centuries. -

Book-3-Durga-Puja FINAL

BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA NEW AGE PUROHIT DARPAN! Bd¤¢eL f¤f¤−l¡¢qa−l¡¢qa cfÑZ! Book 3 DURGA PUJA dugÑA pUjA Purohit (priests) Kanai L. Mukherjee – Bibhas Bandyopadhyay Editor Aloka Chakravarty Publishers Association of Grandparents of Indian Immigrants, USA POBox 50032, Nashvillle, TN 37205 ([email protected]) Distributor Eagle Book Bindery Cedar Rapids. IA 52405 Fourth Edition i BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA LIST OF AUDIOS WITH PAGE REFERENCES Play audio by Control+Click on the link: www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga Audio Pages Titles Links 1 13 Preliminaries http://www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-01- Preliminaries-p-13.mp3 2 66 Bodhan- http://www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-02- Saptami Bodhan-Saptami-p65.mp3 3 118 Mahasthami- http://www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-03- Sandhi Mahastami-Sandhi-p117.mp3 4 144 Mahanabami- http:/www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-04- Dashami Mahanavami-Conclusion-p144.mp3 Video: Prayers and Songs (Page 182) http://www.agiivideo.com/books/video/durga/Durga-stob-mpeg2.mp4 i BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA Global Communication Dilip Som Amitabha Chakrabarti Art work Monidipa Basu Tara Chattoraj Book 3 ii BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA DURGA PUJA dugÑA pUjA Purohit (priests) Kanai L. Mukherjee – Bibhas Bandyopadhyay Editor Aloka Chakravarty Publishers Association of Grandparents of Indian Immigrants, USA POBox 50032, Nashvillle, TN 37205 ([email protected]) Distributor Eagle Book Bindery Cedar Rapids. IA 52405 Fourth Edition iii BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA sîÑEdbmyIQ EdbIQ sîÑErAg vyAphAmÚ| bREþS ib>·u nimtAQ pRNmAim sdA iSbAmÚ|| ibåibåibåÉÉÉÙÛAQ ibåYinlyAQ idbYÙÛAn inbAisnIm| EJAignIQ EJAgjnnIQ ci&kAQ pRNmAmYhmÚÚÚ||||||Ú Sarbadebamayim Devim sarbaroga bhayapaham| Brahmesha Vishnu namitam pranamami sada Shivam || Vindhyastham vindyanilayam divyasthan nibasinim | Joginim jogajananim Chandikam pranamamyaham || Goddess of all Gods, who removes the fear of all diseases Worshipped by Brahma, Vishnu and Maheshwar; I bow to you .with reverence. -

Buddhism Vs Hinduism

Buddhism vs hinduism Continue Hinduism and Buddhism redirects here. For this book, see Religion in India: Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism. Buddhist History Timeline Gautama French Sect Silk Road Transmission Part of the series of Buddhist decline of the Indian Subcontinental After Buddhist Buddhist Modernism Dharma Concept 4 Noble Truth Noble Eight Fold Pas dharma Wheel 5 Aggregate Suffering Unfulmenned Non-Self-Supporting Origin Middle way Emptive Moral Karma Regeneration Saṃsāra Cosmology Buddhist TextsBuddavakana Early Buddhist Texts Tripiṭaka Daiwana Canon Tibetan Canon Canon Canon Missing Three Gems To The Way of Buddhism Three Gems Buddhist Way 5 Commandments Meditation Philosophical Reasoning Devotion Practices Mindful Merit The pilgrimage of the worship of the monastery which forbids the aid to the Enlightenment monastery Nirvāṇa Awakening four stages Acht Pratier Buddha Body Shutva Buddha Buddha Tradition Serada Paris Majayana Hinayana Chinese Chinese Vajayana Tibet Navarana Country Bhutan Cambodia China Korea Laos Mongolian Sri Lanka Taiwan Thailand Tibet Vietnam Overview Religious Portal vte Hindu History History Indian History Veda Religion Śramaṇa Tribal Religious Major Traditional Vaish navism Saktism Smartism Saminarianism Trimurtis Trimurti Brahma Vishnu Shiva Other Major Devas / Devis Vedic Indra Agni Prajapati Rudra Debi Saraswati Usuna Vayu Post-Vedic Durga Ghanesha Hanuman Kali Kartikeya Krishna Lakshmi Parvati Radha Rama Shakti Sita Saminarayan Concepts Worldview Hindu Cosmology Puranic Chronology Hindu mythology -

2017Hinducalendarhouston.Pdf

VEDIC PRIEST & ASTROLOGY CONSULTANT Bhibhudutta Mishra Houston TX, USA Calendar BIBHUDUTTA MISHRA (वै��������- ����व�ु�������) Contact : 713-370-3700 / www.hindupriesthouston.com YEAR: DURMUKHI SOURMANA: DHANUSH – MAKARA AYANA: UTTARA Our astrology calculation based on JPL ephemeris of NASA and CHANDRAMANA: PUSHYA- MAGA RITU: SHISHIRA TAMIL: MARGAZHI – THAI the Hindu festival dates are based as per the Longitude, Latitude, Sunday Monday Sunrise&Tuesday Sunset of Houston,Wednesday Texas. Thursday Friday Saturday PAUSHA S PANCHAMI 28:12 SHASHTHI 27:36 SAPTAMI 26:31 ASHTAMI 24:55 NAVAMI 22:51 DASHAMI 20:22 CHATURTHI 28:20 1 SHATABHISHA 29:47 2 P.BHADRAPADA 29:45 3 U.BHADRAPADA 29:15 4 REVATI 28:15 5 ASHVINI 26:48 6 BHARANI 24:56 7 DHANISHTA 29:21 RK:08:39-09:56 YM:11:12-12:29 RK:15:04 -16:21 YM:09:56-11:13 RK:12:30-13:47 YM:08:39-09:56 RK:13:48-15:05 YM:07:22-08:39 RK:11:14-12:31 YM:15:05-16:23 RK:09:57-11:14 YM:13:49-15:06 RK:16:19-17:36 YM:12:29-13:46 MOON IN MINA 23:48 MASA DURGASTHAMI MOON IN MESHA 04:15 MOON IN KUMBHA 16:59 MASA SKANDA SHASTHI MASA VINAYAKA CHATURTHI EKADASHI 17:33 DVADASHI 14:31 TRAYODASHI 11:24 CHATURDASHI 08:21 PAUSHA K DVITIIYA 25:19 TRITIIYA 24:09 KRITTIKA 22:47 8 ROHINI 20:26 9 MRIGASHIRSHA 18:02 10 PURNIMA 29:34 11 PRATHAMA 27:10 12 PUSHYA 12:19 13 ASLESHA 11:25 14 RK:16:24-17:41 YM:12:32-13:49 RK:08:40-09:57 YM:11:15-12:32 RK:15:08-16:25 YM:09:58-11:15 AARDRA 15:47 PUNARVASU 13:49 RK:11:16-12:34 YM:15:10-16:28 RK:09:58-11:16 YM:13:52-15:10 MOON IN VRISHABHA 06:25 PRADOSHAM MOON IN MITHUNA 07:14 RK:12:33-13:51 -

THE PLACE of DEVOTION Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SARBADHIKARY | The Place THE PLACE OF DEVOTION of Devotion ..... siting and experiencing divinity in bengal-vaishnavism Sukanya Sarbadhikary Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The Place of Devotion South aSia acroSS the diSciplineS South Asia Across the Disciplines is a series devoted to publishing first books across a wide range of South Asian studies, including art, history, philology or textual studies, phi- losophy, religion, and the interpretive social sciences. Series authors all share the goal of opening up new archives and suggesting new methods and approaches, while demonstrat- ing that South Asian scholarship can be at once deep in expertise and broad in appeal. Series Editor: Muzaffar Alam, Robert Goldman, and Gauri Viswanathan Founding Editors: Dipesh Chakrabarty, Sheldon Pollock, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam Funded by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and jointly published by the University of California Press, the University of Chicago Press, and Columbia University Press. 1. Extreme Poetry: The South Asian Movement of Simultaneous Narration, by Yigal Bronner (Columbia) 2. The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab, by Farina Mir (California) 3. Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, by Andrew J. Nicholson (Columbia) 4. The Powerful Ephemeral: Everyday Healing in an Ambiguously Islamic Place, by Carla Bellamy (California) 5. -

Vrajamandala Parikrama 1Compresso

Viaggio lungo le terre di Mathura, Vrindavana e delle dodici foreste sacre di Tridaëãisvâmæ Ôræ Ôræmad Bhaktivedânta Nârâyaëa Gosvâmæ Mahârâja Copyright © Associazione Vaiõëava Gauãæya Vedânta 2! ! Dedicato ai ôræ guru-pâda-padma ÔRÆ GAUDÆYA-VEDANTA-ÂCÂRYA-KESARÆ NITYA-LÆLÂ-PRAVIÕØA OÇ VIÕËUPÂDA AÕØOTTARA-ÔATA ÔRÆ ÔRÆMAD BHAKTI PRAJÑÂNA KEÔAVA GOSVÂMÆ MAHÂRÂJA Il migliore della decima generazione dei discendenti della bhâgavata-paramparâ da Ôræ Caitanya Mahâprabhu, e fondatore della Ôræ Gauãæya Vedânta Samiti e delle sue diramazioni nel mondo ÔRÆ RASIKA YUGÂCÂRYA NITYA-LÆLÂ-PRAVIÕØA OÇ VIÕËUPÂDA AÕØOTTARA-ÔATA ÔRÆ ÔRÆMAD BHAKTIVEDÂNTA NÂRÂYAËA GOSVÂMÆ MAHÂRÂJA Il gioiello della corona tra i seguaci di Ôræla Rûpa Gosvâmæ, il migliore tra le grandi anime, colui che tiene sempre nel suo cuore i piedi di loto di Ôræ Râdha e Krishna, in particolar modo quando Krishna serve Radhika ! 3! vrndavanam sakhi bhuvo vitanoti kirtim yad devaki-suta-padambuja-labdha-laksmi govinda-venum anu matta-mayura-nrtyam preksyadri-sanv-avaratanya-samasta-sattvam (Srimad Bhagavatam 10.21.10) 4! ! ! 5! Volumi di Ôræla Bhaktivedânta Nârâyaëa Mahârâja: In italiano: Il Nettare della Govinda-lælâ Andare oltre Vaikuëøha La vera concezione di Ôræ Guru-tattva L’essenza di tutte le istruzioni Jaiva-dharma 1-2-3 Ôræ Gaudæya Gæti Guccha Ôræ Bhajana Rahasya Raggi di Armonia Lettere dall’America La Via dell’Amore Ôræ Harinâma Mahâmantra Il percorso degli otto Rasa Prema-samput Ôræmad Bhagavad-gætâ vol.1-2-3 Oltre il Nirvana Ôræ Vrâjamandala Parikrama Prema-pradipa Bhakti-rasayana Bhakti-tattva-viveka Ôræ Brahma Samhita Ôræ Gætâ Govinda Associazione Vaiõëava Gauãæya Vedânta Cantone Salero 5 - 13865 Curino (BI) Italia Tel. -

Scheduled Castes in Delhi, Monograph Series, Part V-B, Vol

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 MONOGRAPH SERIES Volume XIX Part V-B SCHEDULED CASTES IN DELHI s. R. GANDOTRA. OJ the Indian Administrative ·Service Director oj Oensus Operf!;tions, JJelh~ \ \ Statements made, views expressed or conclusions drawn in this report are wholly the responsibility of the author alone in his personal capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of the Government. FOREWORD The Indian Census has had the privilege of presenting authentic ethnographic accounts of Indian Communities. It was usual in all censuses to collect and publish information on race, tribes and castes. The Constitution lays down that "the State shall promote with sp;cial care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sec tions of the people and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist states in fulfilling their responsibilities in this regard the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the President under the constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include or exclude from the lists any caste or tribe. No other source can claim the same authenticity and comprehensiveness as the Census of India to help the Government i:a taking decisions on matters such as these. Therefore, besides the statistical data provided by the 1961 Census, the preparation of detailed ethnographic notes on a selection of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in each State and Union 'Territory was taken up as an ancillary study. -

SIEMENS LIMITED List of Outstanding Warrants As on 18Th March, 2020 (Payment Date:- 14Th February, 2020) Sr No

SIEMENS LIMITED List of outstanding warrants as on 18th March, 2020 (Payment date:- 14th February, 2020) Sr No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A P RAJALAKSHMY A-6 VARUN I RAHEJA TOWNSHIP MALAD EAST MUMBAI 400097 A0004682 49.00 2 A RAJENDRAN B-4, KUMARAGURU FLATS 12, SIVAKAMIPURAM 4TH STREET, TIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI 600041 1203690000017100 56.00 3 A G MANJULA 619 J II BLOCK RAJAJINAGAR BANGALORE 560010 A6000651 70.00 4 A GEORGE NO.35, SNEHA, 2ND CROSS, 2ND MAIN, CAMBRIDGE LAYOUT EXTENSION, ULSOOR, BANGALORE 560008 IN30023912036499 70.00 5 A GEORGE NO.263 MURPHY TOWN ULSOOR BANGALORE 560008 A6000604 70.00 6 A JAGADEESWARAN 37A TATABAD STREET NO 7 COIMBATORE COIMBATORE 641012 IN30108022118859 70.00 7 A PADMAJA G44 MADHURA NAGAR COLONY YOUSUFGUDA HYDERABAD 500037 A0005290 70.00 8 A RAJAGOPAL 260/4 10TH K M HOSUR ROAD BOMMANAHALLI BANGALORE 560068 A6000603 70.00 9 A G HARIKRISHNAN 'GOKULUM' 62 STJOHNS ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A6000410 140.00 10 A NARAYANASWAMY NO: 60 3RD CROSS CUBBON PET BANGALORE 560002 A6000582 140.00 11 A RAMESH KUMAR 10 VELLALAR STREET VALAYALKARA STREET KARUR 639001 IN30039413174239 140.00 12 A SUDHEENDHRA NO.68 5TH CROSS N.R.COLONY. BANGALORE 560019 A6000451 140.00 13 A THILAKACHAR NO.6275TH CROSS 1ST STAGE 2ND BLOCK BANASANKARI BANGALORE 560050 A6000418 140.00 14 A YUVARAJ # 18 5TH CROSS V G S LAYOUT EJIPURA BANGALORE 560047 A6000426 140.00 15 A KRISHNA MURTHY # 411 AMRUTH NAGAR ANDHRA MUNIAPPA LAYOUT CHELEKERE KALYAN NAGAR POST BANGALORE 560043 A6000358 210.00 16 A MANI NO 12 ANANDHI NILAYAM -

List AWS Educate Institutions

Educate Institution City Country 1337 KHOURIBGA Morocco 1daoyun 无锡 China 3aaa Apprenticeships Derby United Kingdom 3W Academy Paris France 42 São Paulo sao paulo Brazil 42 seoul seoul Korea, Republic of 42 Tokyo Minato-ku Tokyo Japan 42Quebec QUEBEC Canada A P Shah Institute of Technology Thane West India A. D. Patel Institute of Technology Ahmedabad India A.V.C. College of Engineering Mayiladuthurai India Aalim Muhammed Salegh College of Engineering Avadi-IAF India Aaniiih Nakoda College Harlem United States AARHUS TECH Aarhus N Denmark Aarhus University Aarhus Denmark Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology Kanchipuram(Dt) India Abb Industrigymansium Västerås Sweden Abertay University Dundee United Kingdom ABES Engineering College Ghaziabad India Abilene Christian University Abilene United States Research Pune Pune India Abo Akademi University Turku Finland Academia de Bellas Artes Semillas Ltda Bogota Colombia Academia Desafio Latam Santiago Chile Academia Sinica Taipei Taiwan Academie Informatique Quebec-Canada Lévis Canada Academy College Bloomington United States Academy for Career Exploration PROVIDENCE United States Academy for Urban Scholars Columbus United States ACAMICA Palermo Argentina Accademia di Belle Arti di Cuneo Cuneo Italy Achariya College of Engineering Technology Puducherry India Acharya Institute of Technology Bangalore India Acharya Narendra Dev College New Delhi India Achievement House Cyber Charter School Exton United States Acropolis Institute of Technology & Research, Indore Indore India ACT AMERICAN COLLEGE -

Çré Vrajamandala Parikrama FIRST DRAFT

Çré Vraja-mandala Parikrama Çré Vrajamandala Parikrama FIRST DRAFT by His Divine Grace Çréla Bhakti Ballabh Tértha Gosvämé Mahäräj Sree Chaitanya Gaudiya Math Sector 20-B, Chandigarh 1 Çré Vraja-mandala Parikrama Other books by Srila Bhakti Ballabh Tirtha Goswami Maharaj in english: Sri Chaitanya: His Life and Associates A Taste of Transcendence Sages of Ancient India Suddha Bhakti Daçavatära Hari Katha and Vaishnava Aparadha Nectar of Hari Katha The Holy life of Srila B.D. Madhava Goswami Maharaj Sri Archana Paddhati Affectionately Yours Sri Guru-Tattva The Philosophy of Love © Sree Chaitanya Gauòiya Maöh,2005 Small portions of this work may be reproduced and quoted with proper acknowledgement of the author and the publisher. Significant portions may be reproduced and quoted; however, the author and publisher request that a copy of the work in which they are reproduced be provided to them for their information. The copyright remains with the publisher in all cases. Printed in India by Sree Chaitanya Gauòiya Maöh, Sector 20B, Chandigarh – 160020 Ph.: +91.172.2708788 Website: www.sreecgmath.org & www.gokul.org.uk Email. [email protected] 2 Çré Vraja-mandala Parikrama Contents • Ιntroduction • First Camp - Mathura • Second Camp - Goverdhan • Third Camp - Barasana • Fourth Camp - Nandagrama • Fifth Camp - Gokul • Sixth Camp - Vrindavan 3 Çré Vraja-mandala Parikrama 4 Çré Vraja-mandala Parikrama Introduction In 1932, starting from the holy appearance day of Sriman Madhvacarya, Çréla Bhakti Siddhänta Sarasvaté Prabhupäda performed a one month long circumambulation of Çré Vraja-mandala along with many devotees from various parts of India. Çréla Prabhupäda and his associates visited the places of the pastimes of Supreme Lord Çré Kåñëa and performed kirtana.