The Northern Ireland Broadcasting Ban: Some Reflections on Judicial Review, 22 Vand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900

Reading the local paper: Social and cultural functions of the local press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900 by Andrew Hobbs A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire November 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates that the most popular periodical genre of the second half of the nineteenth century was the provincial newspaper. Using evidence from news rooms, libraries, the trade press and oral history, it argues that the majority of readers (particularly working-class readers) preferred the local press, because of its faster delivery of news, and because of its local and localised content. Building on the work of Law and Potter, the thesis treats the provincial press as a national network and a national system, a structure which enabled it to offer a more effective news distribution service than metropolitan papers. Taking the town of Preston, Lancashire, as a case study, this thesis provides some background to the most popular local publications of the period, and uses the diaries of Preston journalist Anthony Hewitson as a case study of the career of a local reporter, editor and proprietor. Three examples of how the local press consciously promoted local identity are discussed: Hewitson’s remoulding of the Preston Chronicle, the same paper’s changing treatment of Lancashire dialect, and coverage of professional football. These case studies demonstrate some of the local press content that could not practically be provided by metropolitan publications. The ‘reading world’ of this provincial town is reconstructed, to reveal the historical circumstances in which newspapers and the local paper in particular were read. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

The Long History of the Royal Hospital in the UK Popular Press: Searching for the RHN in the British Newspaper Archive Database

The long history of the Royal Hospital in the UK popular press: searching for the RHN in the British Newspaper Archive database Examples of the Hospital newspaper advertisements which were published during 1980s During the past few months, I have been surveying the British Newspaper Archive for mentions of the Hospital. It has been an interesting deep dive into this online database of digitised newspaper articles, with over 40 million pages to search through. What I found was thousands of references to the hospital which I have only really scrapped the surface of what is there about the hospital in the past. In this report, I will summarise some of the key types of items that were published about the hospital and provide some notable highlights from my initial research. What is the British Newspaper Archive? The British Newspaper Archive is a web resource created by the British Library and the genealogy company, findmypast. The website contains over 40 million digitised newspaper pages of newspapers held in the British Library collection. The collection includes most of the runs of newspapers published in the UK since 1800. 1 How to search the British Newspaper Archive The British Newspaper Archives digital records include details of the newspaper title, date and place of publication. When searching through the newspapers you are searching through the newspaper text itself which the database can search as it has undergone a scanning process called optical character recognition (OCR) which makes it machine readable. When searching through a historic database it is important to choose keywords that will always likely to come up. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

Broadcasting Act 1981

Broadcasting Act 1981 CHAPTER 68 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I THE INDEPENDENT BROADCASTING AUTHORITY The Authority Section 1. The Independent Broadcasting Authority. 2. Function and duties of Authority. 3. Powers of Authority. General provisions as to programmes 4. General provisions as to programmes. Programmes other than advertisements 5. Code for programmes other than advertisements. 6. Submission of programme schedules for Authority's approval. 7. Programme prizes. Advertisements 8. Advertisements. 9. Code for advertisements. Special provisions relating to the Fourth Channel 10. Provision by Authority of second television service. 11. Nature of the Fourth Channel, and its relation to ITV. 12. Provision of programmes (other than advertisements) for the Fourth Channel. 13. Advertisements on the Fourth Channel. Teletext services 14. Provision of teletext services by Authority. 15. Code for teletext transmissions. A ii c. 68 Broadcasting Act 1981 Advisory committees Section 16. General advisory council and specialist advisory com- mittees etc. 17. National advisory committees for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. 18. Local advisory committees for local sound broadcasts. Provisions applying to all contracts for programmes 19. Duration of contracts for programmes and prior consul- tation etc. 20. Programme contractors. 21. Provisions to be included in contracts for programmes. 22. Provision for news broadcasts. 23. Newspaper shareholdings in programme contractors. 24. Buying and selling of programmes by programme con- tractors. 25. Wages, conditions of employment, and training of persons employed by programme contractors. Sound programme contracts 26. Accumulation of interests in sound programme contracts. Information as to programme contracts etc. 27. Information as to programme contracts and applications for such contracts. -

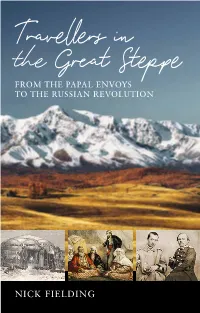

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Friend Or Femme Fatale?: Olga Novikova in the British Press, 1877-1925

FRIEND OR FEMME FATALE?: OLGA NOVIKOVA IN THE BRITISH PRESS, 1877-1925 Mary Mellon A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Louise McReynolds Donald J. Raleigh Jacqueline M. Olich i ABSTRACT MARY MELLON: Friend or Femme Fatale?: Olga Novikova in the British Press, 1877-1925 (Under the direction of Dr. Louise McReynolds) This thesis focuses on the career of Russian journalist Olga Alekseevna Novikova (1840-1925), a cosmopolitan aristocrat who became famous in England for her relentless advocacy of Pan-Slavism and Russian imperial interests, beginning with the Russo- Turkish War (1877-78). Using newspapers, literary journals, and other published sources, I examine both the nature of Novikova’s contributions to the British press and the way the press reacted to her activism. I argue that Novikova not only played an important role in the production of the discourse on Russia in England, but became an object of that discourse as well. While Novikova pursued her avowed goal of promoting a better understanding between the British and Russian empires, a fascinated British press continually reinterpreted Novikova’s image through varying evaluations of her nationality, gender, sexuality, politics and profession. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS FRIEND OR FEMME FATALE?: OLGA NOVIKOVA IN THE BRITISH PRESS, 1877-1925……………….…………...……………………….1 Introduction……………………………………………………………….1 The Genesis of a “Lady Diplomatist”…………………………………...11 Novikova Goes to War…………………………………………………..14 Novikova After 1880…………………………………………………….43 Conclusion……………………………………………………………….59 Epilogue: The Lady Vanishes..………………………………………….60 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………….63 iii The removal of national misunderstandings is a task which often baffles the wisdom of the greatest statesmen, and defies the effort of the most powerful monarchs. -

Freeoom of Religion in England

FREEOOM OF RELIGION IN ENGLAND K. D. EWING King's College, University of London SUMMARY l. INTRODUCTORY. II. THE EsTABLISHED CHURCH. III. STATE SUPPORT POR RELIGION. l. Blasphemy. 2. Sunday Trading. 3. Education. a) Religious Instruction. b) Collective Worship. e) The Right to be Excused. IV. RELIGIOUS ÜBSERVANCE AND CoLLECTIVE WoRSHIP. l. The European Convention on Human Rights. 2. Race Relations Act 1976. 3. Religion and Conscience. 4. Protection for Collective Worship. 5. Freedom of Religious Expression. a) Broadcasting. b) Public Meetings and Rallies. V. CoNCLUSION. l. lNTRODUCTORY The purpose of this paper is to provide a general survey of the law relating to religion in England and Wales. The study excludes the position in Scotland where a different legal regime applies 1. In dealing with the position in England and Wales, attention will be directed to three general questions. The :first relates to the established Church, in particular the rights, privileges and duties of the Church of England. The second relates to the way in which the law is used as a means of state support for 1 See EwING and FINNIE, Civil Liberties in Scotland, Cases and Materials, Second Edi tion, 1988 (W. Green & Son: Edinburgh), Chapter 6. 313 religion generally but Christianity in particular. Here we are concerned with the law of blasphemy which protects Christian religion from abuse; the law of Sunday Trading which eliminates unnecessary distractions from the Christian duty to at tendance at public worship; and the law of education which instills and drills Christian religious belief into children in the schools. The third general question tackled in this paper relates to the way in which the law protects the freedom of religious observance and worship. -

Original Newspapers

Title Place County State Country Call No. Year Month + Day Format Condition Notes 100 Years in Bandera Bandera Bandera TX 2-6/285 1953 Original by J. Martin Hunter Ancient Order of United Aug 01 Original A. O. U. W. Guide Bentonville Benton AR 2-7L/99 1896 Workman, TX Jurisdiction Abilene Reporter-News Abilene Taylor TX 2-1/739 1981 Mar 15 Original Abilene's 100th year Abilene Reporter-News Abilene Taylor TX 2-6/162 1941 Sep 28 Original Abilene Reporter-News Abilene Taylor TX 2-6/468 1956 Apr 08 Original Abingdon Virginian Abingdon Washington VA 2-6/368 1869 May 28 Photocopy Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-4/42 1928 Aug 09 - Dec Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/137 1928 Aug 09, 23 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/137 1928 Nov 01, 15 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/137 1928 Oct 04, 11, 18, 25 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/137 1928 Sep 06, 11, 13, 20, 27 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/387 1928 Aug 09 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/387 1928 Oct 11, 18, 25 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/387 1928 Sep 06, 13, 20 Original Advance Chicago Cook IL 2-6/479 1885 Mar 12 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1928 Aug 09, 23 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1928 Dec 15 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1928 Jan 15 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1928 Nov 01, 15 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1928 Oct 04, 11, 18, 25 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1928 Sep 06, 13, 20, 27 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1929 Apr 15 Original Advance Dallas Dallas TX 2-6/73 1929 -

Broadcasting Committee

Broadcasting Committee Alun Davies Chair Mid and West Wales Peter Black Paul Davies South Wales West Preseli Pembrokeshire Nerys Evans Mid and West Wales Contents Section Page Number Chair’s Foreword 1 Executive Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 Legislative Framework 4 3 Background 9 4 Key Issues 48 5 Recommendations 69 Annex 1 Schedule of Witnesses 74 Annex 2 Schedule of Committee Papers 77 Annex 3 Respondents to the Call for Written Evidence 78 Annex 4 Glossary 79 Chair’s Foreword The Committee was established in March 2008 and asked to report before the end of the summer term. I am very pleased with what we have achieved in the short time allowed. We have received evidence from all the key players in public service broadcasting in Wales and the United Kingdom. We have engaged in lively debate with senior executives from the world of television and radio. We have also held very constructive discussions with members of the Welsh Affairs Committee and the Scottish Broadcasting Commission. Broadcasting has a place in the Welsh political psyche that goes far beyond its relative importance. The place of the Welsh language and the role of the broadcast media in fostering and defining a sense of national identity in a country that lacks a national press and whose geography mitigates against easy communications leads to a political salience that is wholly different from any other part of the United Kingdom. Over the past five years, there has been a revolution in the way that we access broadcast media. The growth of digital television and the deeper penetration of broadband internet, together with developing mobile phone technology, has increased viewing and listening opportunities dramatically; not only in the range of content available but also in the choices of where, when and how we want to watch or listen. -

Au Royaume-Uni El Derecho De Autor En El Reino Unido

NOUVELLES DU ROYAUME UNI NOVEDADES DE REINO UNIDO Le droit d'auteur El derecho de autor au Royaume-Uni en el Reino Unido 1. Introduction 1. Introducción La législation du Royaume-Uni sur La legislación del Reino Unido le droit d'auteur se résume essentiel- referente al derecho de autor se re- lement à la loi sur le droit d'auteur duce esencialmente a la ley sobre el de 1956 (Copyright Act 1956), qui derecho de autor de 1956 (Copyright n'a connu que des amendements rela- Act 1956), que sólo ha sufrido en- tivement mineurs depuis son entrée miendas relativamente pequenas des- en vigueur le 1er juin 1957 (1). Ce de su puesta en vigor, el 1° de junio droit a été clarifié ou modifié à de de 1957 (1). Ese derecho ha sido nombreuses reprises par des déci- clarificado o modificado en nume- sions judiciaires, qui peuvent avoir rosas ocasiones por decisiones judi- le statut de précédents impératifs ou ciales, que pueden tener o no el esta- non. Malgré les tentatives des tribu- tuto de precedentes imperativos. A naux, le droit d'auteur du Royaume- pesar de los intentos de los tribu- Uni ne s'est pas suffisamment adapté nales, el derecho de autor del Reino pour répondre aux exigences de ceux Unido no se ha adaptado suficien- qui prétendent qu'il est incapable temente para responder a las exigen- de satisfaire aux besoins de l'ère cias de los que pretenden que es in- des techniques modernes. Mais cette capaz de satisfacer las necesidades impuissance du droit d'auteur d'au- de la era de las técnicas modernas. -

Broadcasting Act 1981

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Broadcasting Act 1981. (See end of Document for details) Broadcasting Act 1981 1981 CHAPTER 68 PART I THE INDEPENDENT BROADCASTING AUTHORITY The Authority 1 The Independent Broadcasting Authority. (1) The authority called the Independent Broadcasting Authority shall continue in existence as a body corporate. (2) The Authority shall consist of— (a) a Chairman and a Deputy Chairman, and (b) such number of other members, not being less than five, as the Secretary of State may from time to time determine. (3) Unless and until the Secretary of State otherwise determines by notice in writing to the Authority, a copy of which shall be laid before each House of Parliament, the number of those other members shall be ten. (4) Schedule 1 shall have effect with respect to the Authority. 2 Function and duties of Authority. (1) The function of the Authority shall be to provide, in accordance with this Act and until [F131st December 2005], television and local sound broadcasting services, additional in each case to those of the BBC and of high quality (both as to the transmission and as to the matter transmitted), for so much of the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands as may from time to time be reasonably practicable. (2) It shall be the duty of the Authority— (a) to provide the television and local sound broadcasting services as a public service for disseminating information, education and entertainment; 2 Broadcasting Act 1981 (c. 68) Part I – The Independent Broadcasting Authority Document Generated: 2021-05-13 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Broadcasting Act 1981.