P.1 of 7 Spectacular Loss of Performance Between Seasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine News - June 2021

Press information 18 /06/2021 ALPINE NEWS - JUNE 2021 Upcoming news Focus on … Alpine Cars and Alpine F1 Team, preparing the cars of tomorrow Did you know? Recap of the latest news Alpine A110 LÉGENDE GT 2021 available for testing at the France Park Fleet UPCOMING NEWS / Story - A480: The alchemy of tire management The A480 engineers explain the alchemy of tire management. / Sports calendar [F1] The French Grand Prix takes places at Le Castellet! Austrian Grand Prix on the Spielberg circuit on June 27th and July 4th. The cars will meet again on July 18th at Silverstone for the British Grand Prix. [WEC] The 6 Hours of Monza will mark the third race of the WEC season, to be held on July 18th. [CUP] The Spa-Francorchamps circuit will host the Alpine Elf Europa Cup on June 20th. FOCUS ON… ALPINE CARS AND ALPINE F1 TEAM, PREPARING THE CARS OF TOMORROW For Alpine, aerodynamics is the new frontier for sports car performance (speed, range). As part of the development of the brand's future models, Alpine Cars' engineers have called on the expertise and methods of the Alpine F1 Team's aerodynamicists based in Enstone The study work involved the A110, simultaneously conducted from the wind tunnel in France and Enstone with the Alpine F1 Team engineers. The A110 was equipped with a Rake made of 160 sensors and four scanners to collect and process information. The car was also equipped with surface pressure sensors to measure the air pressure on the bodywork and to identify areas of low and high pressure. -

Miura P400 Lamborghini’S Bullish Move

BUICK SERIES 50 SUPER HONDA CBX MICROCARS R50.50 incl VAT August 2018 MIURA P400 LAMBORGHINI’S BULLISH MOVE NOT FOR LIGHTWEIGHTS LAND-ROVER TREK 10-YEAR ALFA GTA REPLICA BUILD CAPE TOWN TO LONDON SIX DECADES AGO CHEVROLET BUSINESS COUPÉ | NER-A-CAR | CARS OF THE KRUGER CONTENTS — CARS BIKES PEOPLE AFRICA — AUGUST 2018 LATE NIGHTS FOR THE LONG RUN A LOYAL STAR 03 Editor’s point of view 72 Rudolf Uhlenhaut CLASSIC CALENDAR THE FAST CLIMBER 06 Upcoming events 76 Honda CBX NEWS & EVENTS POCKET POWER 12 All the latest from the classic scene 82 Bubble cars and microcars – Part 1 THE HURST SHIFTER THE ABC OF LUBRICATION 20 A gliding light 90 Tech talk THE YOUNGTIMER CONSERVING WILDLIFE 22 Defending the cult classics 92 2018 Fiat Panda TwinAir 4x4 Cross LETTERS SUCKERS FOR PUNISHMENT 24 Have your say 93 CCA project cars CARBS & COFFEE GEARBOX 28 Cars of the Kruger Park 96 Classified adverts KABOOM! KB KEEPS CLIMBING 32 40 years of the Isuzu bakkie NEARLY A CAR 46 36 The Ner-A-Car motorcycle A BULLISH MOVE 40 Lamborghini Miura SAFE MY MATE! 46 Buick Series 50 Super NOT FOR LIGHTWEIGHTS 50 Alfa Romeo GTA homage MASTERFUL BUSINESS 56 56 Chevrolet Business Coupé resto-mod LANDY OF HOPE & GLORY 62 Cape Town to London 60 years ago HISTORIC RACING – THE FUTURE 68 2018 Le Mans Classic www.classiccarafrica.com | August 2018 | 1 From specialist metal fabrication, welding, cutting, panel restoration and spraypainting, right through to glass restoration, auto trimming, electrical work and mechanical rebuilds. Give FUEL a call today to see if we can help you with turning your ideas into reality Exotic Car Servicing & Repairs Mechanical & Cosmetic Restoration Custom One-Off Projects. -

On the Road in New Vantage, 2018'S Hottest Sports

REPRINTED FROM CAR MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 2018 ASTON RISING! On the road in new Vantage, 2018’s hottest sports car PLUS: Reborn DB4 GT driven! Valkyrie’s F1 tech secrets! February 2018 | CARMAGAZINE.CO.UK DB4 GT VALKYRIE THEY’VE YOUR GUIDED A SENSATIONAL NEW VANTAGE FAITHFULLY T O U R O F REPRODUCED A S T O N ’ S THEIR ICONIC HYPERCAR BY RACER – WE THE MEN WHO EPIC ENGINES AND ELECTRONICS FROM AMG DRIVE IT MADE IT VANTAGE A N E X C L U S I V E RIDE IN A COSY RELATIONSHIP WITH RED BULL 2018’S MOST EXCITING A NEW EX-MCLAREN TEST PILOT SPORTS CAR DB11 SALES SUCCESS, A NEW FACTORY AND FULL-YEAR PROFITS IN 2017 A V12 HYPERCAR TO REDEFINE THE CLASS HERITAGE TO DIE FOR… …WHY 2018 IS ALREADY ASTON’S YEAR CARMAGAZINE.CO.UK | February 2018 February 2018 | CARMAGAZINE.CO.UK Aston special New Vantage SPECIAL FTER 12 YEARS' sterling service, the old Vantage has finally been put out to pasture. Its replacement is this vision in eye-melting lime green, and it’s by no means just a styling refresh – the new Vantage is powered by a 4.0-litre twin-turbo V8 from AMG (as deployed in the V8 DB11), uses a new aluminium architecture with Aa shorter wheelbase than a 911’s and boasts a gorgeous interior with infotainment pinched from the latest Mercedes-Benz S-Class. Admittedly the new car shares parts with the DB11 – suspension, for example – but 70 per cent are bespoke. The days of Aston photocopying old blueprints and changing the scale are gone. -

Hitlers GP in England.Pdf

HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND Donington 1937 and 1938 Christopher Hilton FOREWORD BY TOM WHEATCROFT Haynes Publishing Contents Introduction and acknowledgements 6 Foreword by Tom Wheatcroft 9 1. From a distance 11 2. Friends - and enemies 30 3. The master’s last win 36 4. Life - and death 72 5. Each dangerous day 90 6. Crisis 121 7. High noon 137 8. The day before yesterday 166 Notes 175 Images 191 Introduction and acknowledgements POLITICS AND SPORT are by definition incompatible, and they're combustible when mixed. The 1930s proved that: the Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, when the President of the International Olympic Committee threatened to cancel the Games unless the anti-semitic posters were all taken down now, whatever Adolf Hitler decrees; the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin and Hitler's look of utter disgust when Jesse Owens, a negro, won the 100 metres; the World Heavyweight title fight in 1938 between Joe Louis, a negro, and Germany's Max Schmeling which carried racial undertones and overtones. The fight lasted 2 minutes 4 seconds, and in that time Louis knocked Schmeling down four times. They say that some of Schmeling's teeth were found embedded in Louis's glove... Motor racing, a dangerous but genteel activity in the 1920s and early 1930s, was touched by this, too, and touched hard. The combustible mixture produced two Grand Prix races at Donington Park, in 1937 and 1938, which were just as dramatic, just as sinister and just as full of foreboding. This is the full story of those races. -

Scaricamento

n. 357 26 luglio 2016 Ferrari, dove vai? A un anno dalla vittoria di Vettel In Ungheria la Rossa è fuori dal podio, lontana dalla Mercedes, incalzata dalla Red Bull. E anche sul 2017 non ci sono certezze FORMULA 1 Test a Barcellona Registrazione al tribunale Civile di Bologna con il numero 4/06 del 30/04/2003 www.italiaracing.net A cura di: Massimo Costa Stefano Semeraro Marco Minghetti Fotografie: Photo4 Realizzazione: Inpagina srl Via Giambologna, 2 40138 Bologna Tel. 051 6013841 Fax 051 5880321 [email protected] © Tutti gli articoli e le immagini contenuti nel Magazine Italiaracing sono da intendersi a riproduzione riservata ai sensi dell'Art. 7 R.D. 18 maggio 1942 n.1369 diBaffi Il graffio GP UNGHERIA Il caso 4 Bandiere gialle non rispettate che passano impunite, regole cambiate fra un gara e l'altra: la F.1 è sempre più incomprensibile. Non più soltanto ai fan, ma anche a chi deve interpretarla in pista Quando la regola sregola 5 GP UNGHERIA Il caso 6 Stefano Semeraro Le regole servono, ci mancherebbe altro. Rules are rules, dicono gli inglesi. Ma troppe regole? E troppi cambiamenti alle regole? E regole incerte nel- l'applicazione? Il weekend di Budapest ha riaperto il fronte della contesta- zione alla FIA, colpevole secondo tanti di aver aggrovigliato troppo la matassa della Massima serie, che peraltro liscia e senza nodi non è stata mai, anzi. Sta- volta però il fronte è ampio, comprende un'ampia fetta di spettatori che fa- ticano a stare dietro alle regole e al funzionamento del Circus, i giornalisti – il cui compito, va bene, è quello di criticare, si spera con criterio – e anche i piloti che sono stanchi di vedersi cambiare sotto il naso codici e procedure. -

Formula 1 Race Car Performance Improvement by Optimization of the Aerodynamic Relationship Between the Front and Rear Wings

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Engineering FORMULA 1 RACE CAR PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT BY OPTIMIZATION OF THE AERODYNAMIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FRONT AND REAR WINGS A Thesis in Aerospace Engineering by Unmukt Rajeev Bhatnagar © 2014 Unmukt Rajeev Bhatnagar Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2014 The thesis of Unmukt R. Bhatnagar was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark D. Maughmer Professor of Aerospace Engineering Thesis Adviser Sven Schmitz Assistant Professor of Aerospace Engineering George A. Lesieutre Professor of Aerospace Engineering Head of the Department of Aerospace Engineering *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract The sport of Formula 1 (F1) has been a proving ground for race fanatics and engineers for more than half a century. With every driver wanting to go faster and beat the previous best time, research and innovation in engineering of the car is really essential. Although higher speeds are the main criterion for determining the Formula 1 car’s aerodynamic setup, post the San Marino Grand Prix of 1994, the engineering research and development has also targeted for driver’s safety. The governing body of Formula 1, i.e. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) has made significant rule changes since this time, primarily targeting car safety and speed. Aerodynamic performance of a F1 car is currently one of the vital aspects of performance gain, as marginal gains are obtained due to engine and mechanical changes to the car. Thus, it has become the key to success in this sport, resulting in teams spending millions of dollars on research and development in this sector each year. -

1911: All 40 Starters

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ROOKIES BY YEAR 1911: All 40 starters 1912: (8) Bert Dingley, Joe Horan, Johnny Jenkins, Billy Liesaw, Joe Matson, Len Ormsby, Eddie Rickenbacker, Len Zengel 1913: (10) George Clark, Robert Evans, Jules Goux, Albert Guyot, Willie Haupt, Don Herr, Joe Nikrent, Theodore Pilette, Vincenzo Trucco, Paul Zuccarelli 1914: (15) George Boillot, S.F. Brock, Billy Carlson, Billy Chandler, Jean Chassagne, Josef Christiaens, Earl Cooper, Arthur Duray, Ernst Friedrich, Ray Gilhooly, Charles Keene, Art Klein, George Mason, Barney Oldfield, Rene Thomas 1915: (13) Tom Alley, George Babcock, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Cooper, C.C. Cox, John DePalma, George Hill, Johnny Mais, Eddie O’Donnell, Tom Orr, Jean Porporato, Dario Resta, Noel Van Raalte 1916: (8) Wilbur D’Alene, Jules DeVigne, Aldo Franchi, Ora Haibe, Pete Henderson, Art Johnson, Dave Lewis, Tom Rooney 1919: (19) Paul Bablot, Andre Boillot, Joe Boyer, W.W. Brown, Gaston Chevrolet, Cliff Durant, Denny Hickey, Kurt Hitke, Ray Howard, Charles Kirkpatrick, Louis LeCocq, J.J. McCoy, Tommy Milton, Roscoe Sarles, Elmer Shannon, Arthur Thurman, Omar Toft, Ira Vail, Louis Wagner 1920: (4) John Boling, Bennett Hill, Jimmy Murphy, Joe Thomas 1921: (6) Riley Brett, Jules Ellingboe, Louis Fontaine, Percy Ford, Eddie Miller, C.W. Van Ranst 1922: (11) E.G. “Cannonball” Baker, L.L. Corum, Jack Curtner, Peter DePaolo, Leon Duray, Frank Elliott, I.P Fetterman, Harry Hartz, Douglas Hawkes, Glenn Howard, Jerry Wonderlich 1923: (10) Martin de Alzaga, Prince de Cystria, Pierre de Viscaya, Harlan Fengler, Christian Lautenschlager, Wade Morton, Raoul Riganti, Max Sailer, Christian Werner, Count Louis Zborowski 1924: (7) Ernie Ansterburg, Fred Comer, Fred Harder, Bill Hunt, Bob McDonogh, Alfred E. -

Bernd Rosemeyer

Sidepodchat – Bernd Rosemeyer Christine: This is show three of five, where Steven Roy turns his written words into an audio extravaganza. These posts were originally published at the beginning of the year on Sidepodcast.com but they are definitely worth a second airing. Steven: Bernd Rosemeyer. Some drivers slide under the door of grand prix racing unnoticed and after serving a respectable apprenticeship get promoted into top drives. Some, like Kimi Räikkönen, fly through the junior formulae so quickly that they can only be granted a license to compete on a probationary basis. One man never drove a race car of any description before he drove a grand prix car and died a legend less than 3 years after his debut with his entire motor racing career lasting less than 1,000 days. Bernd Rosemeyer was born in Lingen, Lower Saxony, Germany on October 14th 1909. His father owned a garage and it was here that his fascination with cars and motor bikes began. The more I learn about Rosemeyer the more he seems like a previous incarnation of Gilles Villeneuve. Like Gilles he had what appeared to be super-natural car control. Like Gilles he seemed to have no fear and like Gilles he didn’t stick rigidly to the law on the road. At the age of 11 he borrowed his father’s car to take some friends for a drive and when at the age of 16 he received his driving license it was quickly removed after the police took a dim view to some of his stunt riding on his motor bike. -

BRDC Bulletin

BULLETIN BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB DRIVERS’ RACING BRITISH THE OF BULLETIN Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB Volume 30 No 2 2 No 30 Volume • SUMMER 2009 SUMMER THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB President in Chief HRH The Duke of Kent KG Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 President Damon Hill OBE CONTENTS Chairman Robert Brooks 04 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 56 OBITUARIES Directors 10 Damon Hill Remembering deceased Members and friends Ross Hyett Jackie Oliver Stuart Rolt 09 NEWS FROM YOUR CIRCUIT 61 SECRETARY’S LETTER Ian Titchmarsh The latest news from Silverstone Circuits Ltd Stuart Pringle Derek Warwick Nick Whale Club Secretary 10 SEASON SO FAR 62 FROM THE ARCHIVE Stuart Pringle Tel: 01327 850926 Peter Windsor looks at the enthralling Formula 1 season The BRDC Archive has much to offer email: [email protected] PA to Club Secretary 16 GOING FOR GOLD 64 TELLING THE STORY Becky Simm Tel: 01327 850922 email: [email protected] An update on the BRDC Gold Star Ian Titchmarsh’s in-depth captions to accompany the archive images BRDC Bulletin Editorial Board 16 Ian Titchmarsh, Stuart Pringle, David Addison 18 SILVER STAR Editor The BRDC Silver Star is in full swing David Addison Photography 22 RACING MEMBERS LAT, Jakob Ebrey, Ferret Photographic Who has done what and where BRDC Silverstone Circuit Towcester 24 ON THE UP Northants Many of the BRDC Rising Stars have enjoyed a successful NN12 8TN start to 2009 66 MEMBER NEWS Sponsorship and advertising A round up of other events Adam Rogers Tel: 01423 851150 32 28 SUPERSTARS email: [email protected] The BRDC Superstars have kicked off their season 68 BETWEEN THE COVERS © 2009 The British Racing Drivers’ Club. -

The Chequered Flag

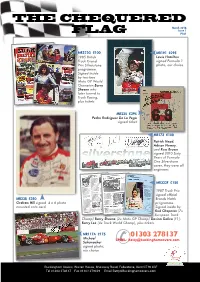

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic. -

P9 Challenge RACE WEEKEND Red-Bull-Ring Fischer Sportpromotion Gmbh BOSS GP 21 - 23 May 2021 Result of Race 2 Red Bull Ring - 4318 Mtr

P9 Challenge RACE WEEKEND Red-Bull-Ring Fischer Sportpromotion GmbH BOSS GP 21 - 23 May 2021 Result of Race 2 Red Bull Ring - 4318 mtr. Started : 17 Classified : 14 Not Classified : 3 Avg. Pos Nbr Name / Entrant Car Cls PIC Gap Total time Fastest In Speed 1 1 Ingo Gerstl (AUT) Toro Rosso F1 - STR1 Cosworth TJOp 1 -- 15 laps -- 23:00.877 1:14.736 15 168.85 Top Speed 2 30 Harald Slegelmilhs (LV) Dallara T12 Gibson Fo 1 22.592 23:23.469 1:19.731 12 166.13 HS Engineering 3 66 Andreas Fiedler (DEU) Dallara GP2 Mecachrome Fo 2 1:02.801 24:03.678 1:22.275 14 161.51 Fiedler Racing 4 47 Walter Steding (DEU) Dallara Formula 2 Mecachrome Fo 3 1:16.440 24:17.317 1:23.720 13 160.00 Scuderia Palladio 5 27 Marco Ghiotto (ITA) Dallara Formula 2 Mecachrome Fo 4 1:16.480 24:17.357 1:19.846 12 159.99 Scuderia Palladio 6 7 Ulf Ehninger (DEU) Benetton F1 - B197 Judd Op 2 1:19.560 24:20.437 1:23.982 14 159.65 ESBA-Racing 7 22 Michael Aberer (AUT) Dallara GP2 Mecachrome Fo 5 1:21.762 24:22.639 1:23.923 13 159.41 MA Motorsport 8 32 Simone Colombo (ITA) Dallara Formula 2 Mecachrome Fo 6 1:26.112 24:26.989 1:20.263 12 158.94 MM International 9 10 Anton Werner (DEU) Dallara IRL - IR8 Chevrolet Ryschka Spec.Op 3 -- 14 laps -- 23:28.270 1:27.892 13 154.53 RY SC HKA Motorsport 10 44 Thomas Jakoubek (AUT) Dallara GP2 Mecachrome Fo 7 3.919 23:32.189 1:26.786 13 154.10 Top Speed 11 15 C hristian Ferstl (AUT) Dallara Formula 2 Mecachrome Fo 8 5.158 23:33.428 1:26.558 14 153.97 Team Top Speed 12 57 Maurizio C opetti (ITA) Dallara World Series by Nissan AER S-L 1 21.343