Nonpoint Source Pollution Management Plan in Quillayute Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities

NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN THE FIRST 10 YEARS (1994–2003) Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities Lita P. Buttolph, William Kay, Susan Charnley, Cassandra Moseley, and Ellen M. Donoghue General Technical Report United States Forest Pacific Northwest PNW-GTR-679 Department of Service Research Station July 2006 Agriculture The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all pro- grams.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

Executive Summary……………………………………………………...… 1

2009 Olympic Knotweed Working Group Knotweed in Sekiu, 2009 prepared by Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board For more information contact: Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board 223 East 4th Street Ste 15 Port Angeles WA 98362 360-417-2442 or [email protected] or http://clallam.wsu.edu/weeds.html CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………...… 1 OVERVIEW MAPS……………………………………………………………… 2 & 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 4 Project Goal……………………………………………………………………… 4 Project Overview………………………………………………………………… 4 2009 Overview…………………………………………………………………… 4 2009 Summary…………………………………………………………………... 5 2009 Project Procedures……………………………………………………….. 6 Outreach………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Funding……………………………………………………………………………. 8 Staff Hours………………………………………………………………………... 8 Participating Groups……………………………………………………………... 9 Observations and Conclusions…………………………………………………. 10 Recommendations……………………………………………………………..... 10 PROJECT ACTIVITIES BY WATERSHED Quillayute River System ………………………………………………………... 12 Big River and Hoko-Ozette Road………………………………………………. 15 Sekiu River………………………………………………………........................ 18 Hoko River………………………………………………………......................... 20 Sekiu, Clallam Bay and Highway 112…………………………………………. 22 Clallam River………………………………………………………..................... 24 Pysht River………………………………………………………........................ 26 Sol Duc River and tributaries…………………………………………………… 28 Forks………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Valley Creek……………………………………………………………………… 36 Peabody Creek…………………………………………………………………… 37 Ennis Creek………………………………………………………………………. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: a 10,700 Year Old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site

Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: a 10,700 year old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site by Jenny Micheal Cohen B.A., University of Victoria, 2010 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology Jenny Micheal Cohen, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: A 10,700 year old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site by Jenny Micheal Cohen B.A., University of Victoria, 2010 Supervisory Committee Dr. Quentin Mackie, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Brian David Thom, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nancy Jean Turner, Outside Member (School of Environmental Studies) ii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Quentin Mackie, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Brian David Thom, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nancy Jean Turner, Outside Member (School of Environmental Studies) This thesis is a case study using paleoethnobotanical analysis of Kilgii Gwaay, a 10,700- year-old wet site in southern Haida Gwaii to explore the use of plants by ancestral Haida. The research investigated questions of early Holocene wood artifact technologies and other plant use before the large-scale arrival of western redcedar (Thuja plicata), a cultural keystone species for Haida in more recent times. The project relied on small- scale excavations and sampling from two main areas of the site: a hearth complex and an activity area at the edge of a paleopond. The archaeobotanical assemblage from these two areas yielded 23 plant taxa representing 14 families in the form of wood, charcoal, seeds, and additional plant macrofossils. -

1 CLIMATE PLAN for the QUILEUTE TRIBE of the QUILEUTE RESERVATION La Push, Washington, 9/30/2016 Prepared by Katherine Krueger

1 CLIMATE PLAN FOR THE QUILEUTE TRIBE OF THE QUILEUTE RESERVATION La Push, Washington, 9/30/2016 Prepared by Katherine Krueger, Quileute Natural Resources, B.S., M.S., J.D. in Performance of US EPA Grant Funds FYs 2015‐2016 TABLE of CONTENTS Preface 2 Executive Summary 4 Introduction to Geography and Governance 6 Risk Assessment 8 Scope of the Plan 10 Assessment of Resources and Threats, with Recommendations 14 Metadata and Tools 14 Sea Level Change 15 Terrestrial (Land) Environment 19 Fresh Water (Lakes, Rivers, Wetlands) 21 Marine Environment 32 Impact on Infrastructure/Facilities 46 Cultural Impacts 49 Appendix 50 Recommendations Summarized 50 Maps 52 Research to Correct the Planet 56 Hazard Work Sheets 57 Resources and Acknowledgements 59 2 Preface: It is important to understand the difference between weather and climate. Weather forecasts cover perhaps two weeks, and if extending into a season, a few months, or even a few years, but climate is weather over decades or even centuries. The National Academies of Sciences put on a slide show about this in March of 2016, in anticipation of their book to be published later this year entitled Next Generation Earth System Prediction. Researchers want to extend weather forecasting capacity, based on modeling, using vast accumulations of prior data, because weather affects so many aspects of our economy. So when we have a summer of unusual drought or a year of constant rain that extends all summer long, it is premature to call this climate change. But when we measure increases of global temperature averages over decades, or see planet‐wide loss of continental ice over decades, we can make statements about climate. -

Northwest Coast Traditional Salmon. Fisheries Systems

NORTHWEST COAST TRADITIONAL SALMON. FISHERIES SYSTEMS OF RESOURCE UTILIZATION by PATRICIA ANN BERRINGER B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Anthropology & Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1982 (c) Patricia Ann Berringer In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 October 18, 1982 e - ii - Abstract The exploitation of salmon resources was once central to the economic life of the Northwest Coast. The organization of technological skills and information brought to the problems of salmon utilization by Northwest Coast fishermen was directed to obtaining sufficient calories to meet the requirements of staple storage foods and fresh consumption. This study reconstructs selective elements of the traditional salmon fishery drawing on data from the ethnographic record, journals, and published observations of the period prior to intensive white settlement. To serve the objective of an ecological perspective, technical references to the habitat and distribution of Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus sp.) are included. -

Gold and Fish Pamphlet: Rules for Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining

WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE Gold and Fish Rules for Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining May 2021 WDFW | 2020 GOLD and FISH - 2nd Edition Table of Contents Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining Rules 1 Agencies with an Interest in Mineral Prospecting 1 Definitions of Terms 8 Mineral Prospecting in Freshwater Without Timing Restrictions 12 Mineral Prospecting in Freshwaters With Timing Restrictions 14 Mineral Prospecting on Ocean Beaches 16 Authorized Work Times 17 Penalties 42 List of Figures Figure 1. High-banker 9 Figure 2. Mini high-banker 9 Figure 3. Mini rocker box (top view and bottom view) 9 Figure 4. Pan 10 Figure 5. Power sluice/suction dredge combination 10 Figure 6. Cross section of a typical redd 10 Fig u re 7. Rocker box (top view and bottom view) 10 Figure 8. Sluice 11 Figure 9. Spiral wheel 11 Figure 10. Suction dredge . 11 Figure 11. Cross section of a typical body of water, showing areas where excavation is not permitted under rules for mineral prospecting without timing restrictions Dashed lines indicate areas where excavation is not permitted 12 Figure 12. Permitted and prohibited excavation sites in a typical body of water under rules for mineral prospecting without timing restrictions Dashed lines indicate areas where excavation is not permitted 12 Figure 13. Limits on excavating, collecting, and removing aggregate on stream banks 14 Figure 14. Excavating, collecting, and removing aggregate within the wetted perimeter is not permitted 1 4 Figure 15. Cross section of a typical body of water showing unstable slopes, stable areas, and permissible or prohibited excavation sites under rules for mineral prospecting with timing restrictions Dashed lines indicates areas where excavation is not permitted 15 Figure 16. -

Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan December 2009 Developed by Shea McDonald and Dwight Barry, Peninsula College Center of Excellence. Contributions and developmental assistance: Chris DeSisto, Tiffany Nabors, Erin Drake, and Aaron Lambert; Western Washington University-Peninsulas; Bill Sanders and Bryan Suslick, Washington Department of Natural Resources; Al Knobbs, Clallam County Fire District 3; Jon Bugher, Clallam County Fire District 2; Phil Arbeiter, Clallam County Fire District 1; Larry Nickey, Olympic National Park; Clea Rome, USDA-NRCS; and Dean Millett, US Forest Service. GIS analysis by Shea McDonald, Chris DeSisto, and Dwight Barry. Cartography by Shea McDonald. Project funded under Title III of the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Policy Context ............................................................................................................................. 7 Healthy Forests Restoration Act ........................................................................................................... 7 National Fire Plan ................................................................................................................................. -

Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: a Review Article

names of individual forts; names of M. Odivetz, and Paul J. Novgorotsev, Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: individual ships 20(3):235-36 Visions of Empire at American “Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: Russian Shadows on the British Northwest International Expositions, 1876-1916, A Review Article,” by Charles E. Coast of North America, 1810-1890: review, 77(2):74; In the People’s Interest: Timberlake, 61(4):217-21 A Study of Rejection of Defence A Centennial History of Montana State A Russian American Photographer in Tlingit Responsibilities, by Glynn Barratt, University, review, 85(2):70 Country: Vincent Soboleff in Alaska, by review, 75(4):186 Ryesky, Diana, “Blanche Payne, Scholar Sergei Kan, review, 105(1):43-44 “Russian Shipbuilding in the American and Teacher: Her Career in Costume Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641-1850, Colonies,” by Clarence L. Andrews, History,” 77(1):21-31 by F. A. Golder, review, 6(2):119-20 25(1):3-10 Ryker, Lois Valliant, With History Around Me: “A Russian Expedition to Japan in 1852,” by The Russian Withdrawal From California, by Spokane Nostalgia, review, 72(4):185 Paul E. Eckel, 34(2):159-67 Clarence John Du Four, 25(1):73 Rylatt, R. M., Surveying the Canadian Pacific: “Russian Exploration in Interior Alaska: An Russian-American convention (1824), Memoir of a Railroad Pioneer, review, Extract from the Journal of Andrei 11(2):83-88, 13(2):93-100 84(2):69 Glazunov,” by James W. VanStone, Russian-American Telegraph, Western Union Ryman, James H. T., rev. of Indian and 50(2):37-47 Extension, 72(3):137-40 White in the Northwest: A History of Russian Extension Telegraph. -

Case Studies of Three Salmon and Steelhead Stocks in Oregon and Washington, Including Population Status, Threats, and Monitoring Recommendations

HOW HEALTHY ARE HEALTHY STOCKS? Case Studies of Three Salmon and Steelhead Stocks in Oregon and Washington, including Population Status, Threats, and Monitoring Recommendations Prepared for the Native Fish Society April 2001 How Healthy Are Healthy Stocks? Case Studies of Three Salmon and Steelhead Stocks in Oregon and Washington, including Population Status, Threats, and Monitoring Recommendations Prepared for: Bill Bakke, Director Native Fish Society P.O. Box 19570 Portland, Oregon 97280 Prepared by: Peter Bahls, Senior Fish Biologist David Evans and Associates, Inc. 2828 S.W. Corbett Avenue Portland, Oregon 97201 Sponsored by the Native Fish Society and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 2001 Please cite this document as follows: Bahls, P. 2001. How healthy are healthy stocks? Case studies of three salmon and steelhead stocks in Oregon and Washington, including population status, threats, and monitoring recommendations. David Evans and Associates, Inc. Report. Portland, Oregon, USA. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Three salmon stocks were chosen for case studies in Oregon and Washington that were previously identified as “healthy” in a coast-wide assessment of stock status (Huntington et al. 1996): fall chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) of the Wilson River, summer steelhead (O. mykiss) of the Middle Fork John Day (MFJD) River, and winter steelhead (O. mykiss) of the Sol Duc River. The purpose of the study was to examine with a finer focus the status of these three stocks and the array of human influences that affect them. The best available information was used, some of which has become available since the 1996 assessment of healthy stocks was conducted. Recommendations for monitoring were developed to address priority data gaps and most pressing threats to the species. -

The Bogachiel River System

The Bogachiel River System Within the Bogachiel River system, a number of stream reaches qualify as shorelines of statewide significance. The mainstem BOGACHIEL (RM 0 – 17.6) contains no reach breaks under the current SMP. The portion of the Bogachiel that flows through the Forks Urban Growth Area (FUGA) extends from approximately RM 8.9 to 10.1. Tributary reaches include the following: BEAR‐BOGACHIEL (RM 0‐4.2); DRY‐BOGACHIEL (RM 0‐.5); MAXFIELD 10 (RM 0‐2.7); MAXFIELD 20 (RM 2.7‐4.4); MILL (RM 0 – 1.3); MURPHY 10 (RM 0‐ 1.7); MURPHY 20 (RM 1.7‐ 2.1); and DRY‐BOGACHIEL (RM 0‐ .5). The portion of MILL CR that is within the FUGA extends from RM .8‐ 1.3. The creek flows outside of FUGA and then returns into FUGA boundaries (RM .1) upstream of its confluence with the Bogachiel. The portion of Mill Creek that is outside of FUGA extends from RM 0.1 ‐ .8. Physical Environment The headwaters of the Bogachiel River lie outside the current planning area in the steep terrain of the Olympic National Park. As it enters the planning unit, it flows in a northwesterly direction with several miles in close proximity to US 101. West of the Forks UGA, its largest tributary, the Calawah River, flows into the Bogachiel. Downstream of the confluence, the River widens and meanders in a westward direction through a broad alluvial valley. Beds of Pleistocene clay, sand, and gravel WRIA 20 Draft ICR June 30, 2011 10 | Page overlie the older rocks throughout most of this region. -

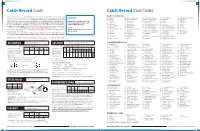

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142.