Exit, Promising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 11-20, 2016

The First Act “High Ho” & “Small World” (Snow White “I Can Go the Distance” (Hercules) Lori Zimmermann of State Farm, Chuck Eckberg of RE/MAX Results, and and the Seven Dwarfs) Hercules, Captain Li Shang “When You Wish Upon a Star” (Pinocchio) Seven Dwarfs, Small Youth Chorus “Trashin’ the Camp” & “Two Worlds Jiminy Cricket, Tinker Bell, All Cast Ending” (Tarzan) “Belle (Bon Jour)” (Beauty & the Beast) DISNEY LEADING LADIES Stomp Guys Belle, Aristocratic Lady, Fishman/Eggman, “Bibidy Bobbidy Boo” (Cinderella) “I’ve Been Dreaming of a True Love’s Kiss” PRESENT Sausage Curi Girl, Baker, Hat Seller, Fairy Godmother, Cinderella, Girls (Enchanted) Shepherd Boy, Lady with Cane, Gaston, Chorus II, “Parents”, Little Brothers, Disney Prince Edward LeFou, Silly Girl1, Silly Girl2, Silly Girl3, Photographers Children, Villagers “Some Day My Prince Will Come” (Snow VILLAINS “Topsy Turvy Day” (Hunchback of Notre White and the Seven Dwarfs) “I’ve Got a Dream” (Tangled) Dame) Snow White Hook Hand Thug, Big Nose Thug, Flynn, Clopin (Jester), Esmerelda, Quasimodo, “So This Is Love” (Cinderella) Rapunzel, Thug Chorus Guards, Villagers Cinderella, Prince Charming “Gaston” (Beauty & the Beast) “One Jump Ahead” (Aladdin) “Once Upon a Dream” (Sleeping Beauty) Gaston, Lefou, Silly Girls, Villagers Aladdin, Soloist, Jasmine, Abu, Villagers, Princess Aurora “Step Sisters Lament” (Cinderella) Group of Ladies “Part of Your World” (Little Mermaid) Portia & Joy “For the First Time in Forever” (Frozen) Ariel “Poor Unfortunate Soul” (Little Mermaid) Anna, Castle Folks -

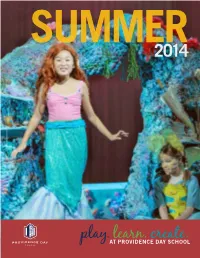

Play. Learn. Create

SUMMER2014 play.AT learn. PROVIDENCE create. DAY SCHOOL To register online visit www.providenceday.org | 704.887.7006 PROVIDENCE DAY SCHOOL 1 play.play. learn. create. WEEK 1: JUNE 2 – 6 WEEK 3: JUNE 16 – 20 COURSE NAME AGE TIME PPAGEAGE COURSE NAME AGE TIME PPAGEAGE Building Dinos B&G 4 – 6 PM 34 Annie B&GBG rg rg 1– 1– 5 5 AM/PM 47 Charger Chill Day Camp B&G rg K – 5 AM/PM 11 Athena’sAthena’s Path G rg 5 – 6 AM/PM 19 Girls Basketball/Basketball/VelocityVelocity G rg 4 – 9 AM 9 Biking B&G rg 6 – 9 AM/PM 10 Girls Just WantWant to G 7–12 AM/PM 13 Boy’sBoys’ All Sports B 7–14 AM/PM 10 Have Fun Cheerleading G 4 –7 AM 11 Hot Shot Hoops B 4–6 AM 9 Cool KidsKid’s Lacrosse,Lacrosse, G rg 1– 8 AM/PM 14 Little Dribblers, Girls G rg K–3 PM 9 Girls Basketball Crafts, Crafts a Go Go B&G rg 1–3 PM 42 Ooze, Glop & Slime B&G 4 – 6 AM 35 Dissecting Critters B&G 10&up PM 34 Roughing It B&G 4&UP4&up AM/PM 36 Fairy TaleTale Magic B&G 4– 6 PM 44 TTennisennis and Swim B&G 4&up4&UP AM 16 From Pencil to B&G rg 3 – 5 PM 43 Ultimate Sleepover G 7–12 AM/PM 27 Paintbrush VideoVideo Game Makers B&G rg 5 – 9 AM/PM 38 Keyboarding B&G 8&up PM 23 WrestlingWrestling B 8 –16 AM 17 Jungalbook BGB&G rg rg 3-10 3-10 AM/PM 50 Leaping Lizards B&G 7&up AM 34 WEEK 2: JUNE 9 – 13 Monster Movie B&G rg 1 – 5 PM 46 COURSE NAME AGE TIME PAGEPAGE Mystical B&G rg K – 2 AM 43 Baseball B 7–12 AM 9 Masterpieces Brushstrokes B&G rg 3 – 5 PM 42 Ooze, Glop and& Slime Slime B&G 4 – 6 PM 35 Catching Critters B&G 4 – 6 AM 34 Origami Pop Ups B&G rg 3 – 6 AM 43 Cool Kids Lacrosse – Boys B rg 1– 8 AM/PM 14 Princess for a WeekWeek G 4 – 6 AM 45 Crazy Cut–Ups B&G rg 1– 3 AM 42 Project Runway,Runway, JR. -

A Disney Spectacular a Disney Spectacular

A DISNEY SPECTACULARA DISNEY SPECTACULAR Summer Stage 2012 Inspired by and written by Kevin Dietzler (As the Summer Stage Song ends, a family dinner table and four chairs are brought out and placed stage right) 1…2…3…shh! (Lights up as we see MOTHER, FATHER, and RUTH seated at the table. It is 1912 and WALT’s 10th birthday. There is a cake, table settings and one present wrapped in brown paper and tied up in yellow string) MOTHER (rising from the table) I wonder what’s taking him so long? Walt? Walter E. Disney, are you coming? It’s time to sing. FATHER Oh, Mother, he’s just excited. Why, you could never get me to sit still when it was my special day. RUTH He’s always on another one of his adventures. MOTHER That boy has got an imagination like no other. WALT (running in) Look out! RUTH Look out for what? WALT The dragon! FATHER A dragon? Where? WALT I was on my way to rescue the sleeping princess from her tower when suddenly the evil witch turned into a fire-breathing dragon. MOTHER Oh, did she? - 1 - WALT Uh-huh! And I’m going to use this magical sword I pulled from a stone to slay the dragon and save the princess. MOTHER Alright there, Prince Charming, but the princess will have to wait. WALT Awww. Why? MOTHER Because there are no swords allowed at the dinner table. Besides, it’s time for us to sing. FATHER, MOTHER, RUTH HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO YOU! HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO YOU! HAPPY BIRTHDAY DEAR WALTER! HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO YOU! FATHER Now make a wish! (WALT pauses then blows out the candles) MOTHER I think your sister has one more present to give you. -

The Little Mermaid

THE LITTLE MERMAID ---------------------- The complete script Compiled by Corey Johanningmeier Portions copyright (c)1989 by Walt Disney Co. ----------------------------------------------------------- (An ocean. Birds are flying and porpoises are swimming happily. From the fog a ship appears crashing through the waves) Sailors: I'll tell you a tale of the bottomless blue And it's hey to the starboard, heave ho Look out, lad, a mermaid be waitin' for you In mysterious fathoms below. Eric: Isn't this great? The salty sea air, the wind blowing in your face . a perfect day to be at sea! Grimsby: (Leaning over side.) Oh yes . delightful . Sailor 1: A fine strong wind and a following sea. King Triton must be in a friendly-type mood. Eric: King Triton? Sailor 2: Why, ruler of the merpeople, lad. Thought every good sailor knew about him. Grimsby: Merpeople! Eric, pay no attention to this nautical nonsense. Sailor 2: But it ain't nonsense, it's the truth! I'm tellin' you, down in the depths o' the ocean they live. (He gestures wildly, Fish in his hand flops away and lands back in the ocean, relieved.) Sailors: Heave. ho. Heave, ho. In mysterious fathoms below. (Fish sighs and swims away.) (Titles. Various fish swimming. Merpeople converge on a great undersea palace, filling concert hall inside. Fanfare ensues.) Seahorse: Ahem . His royal highness, King Triton! (Triton enters dramatically to wild cheering.) And presenting the distinguished court composer, Horatio Thelonious Ignatius Crustaceous Sebastian! (Sebastion enters to mild applause.) Triton: I'm really looking forward to this performance, Sebastian. Sebastian: Oh, Your Majesty, this will be the finest concert I have ever con- ducted. -

Anaheim Overall Score Reports

Anaheim Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance Platinum 1st Place 1 1121 MaMa Mia - Art of the Dance Academy - N Hollywood, CA 109.9 Angelique Calma Platinum 1st Place 2 927 Mother's Gift - Li's Ballet Studio - Temple City, CA 109.3 Jessie Huang Platinum 1st Place 3 620 In My Fashion - Murrieta Dance Project - Murrieta, CA 109.2 Krista Pham Platinum 1st Place 4 608 Roxie - Murrieta Dance Project - Murrieta, CA 109.1 Anneka Tokarchik Platinum 1st Place 4 612 Le Jazz Hot - Murrieta Dance Project - Murrieta, CA 109.1 Kendall Le Platinum 1st Place 5 1151 Black Swan - Li's Ballet Studio - Temple City, CA 109.0 Alvina Wang Gold 1st Place 6 189 That's Not My Name - Beach Cities Stars - Fountain Valley, CA 108.4 Paige Bui Gold 1st Place 6 904 Giselle, Act I - Pointe Ballet LLC - Alhambra, CA 108.4 Catherine Yang Gold 1st Place 7 1065 Hound Dog - Studio 31 Dance Center - Murrieta, CA 108.3 Jalia Murvin Gold 1st Place 8 905 Don Quixote, Act III - Pointe Ballet LLC - Alhambra, CA 108.2 Cynthia Zheng Gold 1st Place 8 983 Christmas Stocking Dance - Li's Ballet Studio - Temple City, CA 108.2 Carolyn Wu Gold 1st Place 9 477 My Little Drum - The Little Dance World - Hacienda Heights, CA 108.0 Sandra Pan Gold 1st Place 10 836 I'm Cute - Kimberly's Dance Studio - Paramount, CA 107.7 Andrea Perez Advanced Platinum 1st Place 1 731 How Do I Look - The Dance Company - Kingsburg, CA 110.7 Bailey Workman Platinum 1st Place 1 1109 Sing Sing Sing - West Coast School of the Arts - Costa Mesa, CA 110.7 Yasmeen Baghdadi Platinum 1st Place 2 -

![6Th-8Th Grade List by ZPD [Book Level] 2017-18 ~1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7706/6th-8th-grade-list-by-zpd-book-level-2017-18-1-4997706.webp)

6Th-8Th Grade List by ZPD [Book Level] 2017-18 ~1

6th-8th Grade List by ZPD [Book Level] 2017-18 ~1 A B C D E 1 ZPD Points Author Title Location 2 3.2 5 Hamilton, Virginia Second Cousins aef 3 3.3 5 Friend, Natasha Bounce caf [stepfamilies] 4 3.3 4 Rhodes, Jewell Parker Ninth Ward caf 5 3.3 5 Spinelli, Jerry Smiles to Go caf 6 3.3 4 Vos, Ida Anna is Still Here hff/fwf 7 3.4 5 Flake, Sharon G. Pinned 8 3.4 6 Hunt, Lynda Mullaly One for the Murphys 9 3.4 6 Mazer, Harry City Light caf 10 3.5 8 Avi City of Orphans ahf 11 3.5 5 Bauer, Joan Tell Me 12 3.5 7 Choldenko, Gennifer Al Capone Does My Shirts Bk1 caf/huf 13 3.5 5 Friend, Natasha Perfect caf 14 3.5 6 Hurwitz, Michele Weber The Summer I Saved the World…in 65 Days 15 3.5 6 Jenkins, Jerry B. Renegade Spirit Bk1: The Tattooed Rats [end times series] 16 3.5 5 Larson, Kirby Duke 17 3.5 4 Mazer, Norma Fox Good Night, Maman fw/hf 18 3.5 9 Moss, Jenny Taking Off 19 3.6 4 Applegate, Katherine The One and Only Ivan 20 3.6 4 Avi Don’t You Know There’s a War On? awf 21 3.6 6 Bauer, Jennifer Close to Famous 22 3.6 7 Knowles, Jo See You at Harry's 23 3.6 4 Lyon, George Ella Borrowed Children caf 24 3.6 7 O'Conner, Sheila Sparrow Road 25 3.6 9 Sepetys, Ruta Between Shades of Gray 26 3.6 7 Spinelli, Jerry Milkweed hf 27 3.7 5 Avi The Good Dog fwa 28 3.7 3 Avi The Christmas Rat caf 29 3.7 6 Bauer, Joan Almost Home 30 3.7 7 Butler, Dori Sliding into Home spf 31 3.7 7 Choldenko, Gennifer Al Capone Does My Homework Bk3 32 3.7 7 Grabenstein, Chris The Crossroads f 33 3.7 4 Haworth, Danette Violet Raines Almost Got Struck by Lightning 34 3.7 4 Holm, Jennifer Turtle in Paradise 35 3.7 5 Jenkins, Jerry B. -

Mermaids and Their Cultural Significance in Literature And

MERMAIDS AND THEIR CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE IN LITERATURE AND FOLKLORE by LARA KNIGHT (Under the Direction of Charles Doyle) ABSTRACT Mythological characters, mermaids represent seductive women and hybrid personas; their dual nature often reflects a conflict within their environment. By studying different popular mermaid appearances in literature and folklore, I can map cultural changes along with ideas and symbols that vary little between cultures. Hans Christian Andersen’s story “The Little Mermaid,” for instance, allows a female character to take charge of her destiny within a patriarchal world; his little mermaid finds a road to salvation she can walk alone, without a man. Many critics have condemned Disney’s adaptation of Andersen’s story because it neglects the spiritual quest. Instead of explaining this shift as a regression, a common trend among scholars, I have considered the film within the context of the 1980s and the context of mermaid traits found in mythology. I have also traced mermaid appearances in American legends of the Flying African. Mermaids represent several cultural variations. INDEX WORDS: Mermaids, Hans Christian Andersen, “Flying African,” “Singing River,” Walt Disney, “The Little Mermaid,” Sirens MERMAIDS AND THEIR CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE IN LITERATURE AND FOLKLORE by LARA KNIGHT A.B., The University of Georgia, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GA 2005 © 2005 Lara Knight All Rights Reserved MERMAIDS AND THEIR CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE IN LITERATURE AND FOLKLORE by LARA KNIGHT Major Professor: Charles Doyle Committee: Jonathan Evans Coburn Freer Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. -

Duluth-Program.Pdf

Meet The Judges Lily Houtkin San Antonio, Texas Originally from San Antonio, TX, Lily is classically trained in Vaganova and has received the highest certificates in all levels of the Checcetti Ballet Technique. At a young age Lily performed in the Ballet West production of “The Nutcracker” and the Fort Worth Ballet production of “Cinderella”, in San Antonio. Lily is also extensively trained in Ballet, Pointe, Jazz, Lyrical, Contemporary, Modern, Hip-Hop, and Tap. She received many Top Elite awards and scholarships which led her to Los Angeles to pursue her professional dance career. Lily has worked with many choreographers including Paula Abdul, Andre Fuentes and many more. She has performed in many stage productions at Disney’s world famous El Capitan Theatre including the World Premieres of “Tarzan” “Toy Story 2” and “Herbie Fully Loaded”. Her film credits include the feature film ”American Beauty”, “Rush Hour In Los Angeles”, and “Zombie Prom”. She has worked on industrials for Taco Bell and Marriott Resorts and has danced for many up and coming artist. Lily is also a certified Pilates Instructor and enjoys helping dancers lengthen their career through the Pilates Method. Lily has recently relocated back to San Antonio to join the Trilogy Dance Center faculty teaching all styles of dance and is the Assistant Artistic Director and choreographer of Insight Dance Ensemble. She is also a member of San Antonio Jazz Ensemble and continues to perform various pieces with them throughout the year. Olivia Fisher Cincinnati, OH Olivia Fisher is a native of Toronto, Canada however she now considers Cincinnati, Ohio home. -

FLOTSAM So Sad, JETSAM So True UR

CHOREOGRAPHY NOTES POOR UNFORTUNATE SOULS INTO BELUGA SEVRUGA URSULA: My dear, sweet child - it's what I live for: to help unfortunate merfolk like yourself. Souls react: U turns to block A from seeing souls; Ts move one on one to block souls; F&J hiss at souls Poor souls, with no one else to turn to . URSULA I admit that in the past I've been a nasty They weren't kidding when they called me, well, a witch U motion to souls; look over at them, but tentacles block when they But you'll find that nowadays react to souls acting like “yes, she is a witch” I've mended all my ways Souls react again on “mended” T’s threaten then turn back toward A Repented, seen the light, and made a switch U and T’s “march” toward A on each phrase (3 big steps). Hands in prayer on “repented,” hands up and look up on “light,” look back to Ariel; U holds up finger/snears. F&J left to mind the souls 3 each. True? Yes.. Souls react “NO!” Ts glare back at them; F&J hiss at them/flash lights And I fortunately know a little magic, All throw down party snaps It's a talent that I always have possessed U pride in herself; Ts wriggle in joy And here lately, please don't laugh U serious look and tone I use it on behalf of the miserable, lonely, and depressed On miserable front Ts look at souls; on lonely middle Ts look at souls; Pathetic! on depressed Ts closest to U look at souls On pathetic Ts all look back at Ariel ALL Poor unfortunate souls! All “march” toward Ariel URSULA U and right hand Ts look right at 3 downstage souls on pain; U and left In pain, in need hand -

Cincinnati Overall Score Reports

Cincinnati Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance 1 921 Born To Entertain - Encore Performing Arts - Berea, KY 82.4 Brianna Berkemeier 2 944 Freakout - Midwest Elite Dance Center - Amelia, OH 81.6 Graff Zayla 3 714 I'm Cute - - Trenton, OH 81.4 Maya Sensel 4 933 Can't Touch This - Midwest Elite Dance Center - Amelia, OH 81.1 Nora Kirkham 5 568 Famous - Hollywood Dance Company - Batavia, OH 80.8 Addi Loudon 6 917 Call Me a Princess - Emerge Dance Academy - Cincinnati, OH 80.5 Kylie McCurry 6 989 Think - Midwest Elite Dance Center - Amelia, OH 80.5 Erryn McCale 7 569 Rockstar - Hollywood Dance Company - Batavia, OH 80.4 Brooklyn Kennedy 7 985 My Boyfriend's Back - New Level Dance Studio - Cincinnati, OH 80.4 Braidyn Mundy 8 461 Lil Miss Swagger - Emerge Dance Academy - Cincinnati, OH 79.5 Anabelle Wurtz Advanced 1 919 I'm Available - Encore Performing Arts - Berea, KY 84.1 Kamryn Hiten 2 478 Vitality - Emerge Dance Academy - Cincinnati, OH 83.5 Savanna Acree 3 990 Little Bird - Midwest Elite Dance Center - Amelia, OH 83.4 Madison Weibel 4 469 Stay Little - Emerge Dance Academy - Cincinnati, OH 82.6 Elliana Kuhlman 5 466 Rock-n-Roll Is King - Emerge Dance Academy - Cincinnati, OH 82.3 Jasmine Nicholls 6 570 Little Alice - Hollywood Dance Company - Batavia, OH 82.2 Mady Cremering 7 35 Hallelujah - Prestige Dance Center - Cincinnati, OH 82.0 Harper Peavley 7 479 Wash That Man - Emerge Dance Academy - Cincinnati, OH 82.0 Ashley Wachtel 8 51 Glamorous Life - Premier Studio for Dance - Loveland, OH 81.9 Abby Laker 8 398 Poor Unfortunate Soul - Fit 4 Kidz - Milford, OH 81.9 Alaina Kellerman 9 474 B.E.A.T. -

THE LITTLE MERMAID Script

1 SCENE 1 - THE OCEAN SURFACE “Fathoms Below” PILOT: I’ll tell you a tale of the bottomless blue SAILORS: And it's hey to the starboard, heave-ho PILOT: Brave Sailor beware, ‘cause a big one’s a brewin’ SAILORS: Mysterious fathoms below! Heave ho! PILOT: I’ll sing you a song of the king of the sea… SAILORS: And it's hey to the starboard, heave-ho PILOT: The ruler of all of the oceans is he… SAILORS: In mysterious fathoms below! ALL: Fathoms below, below, From whence wayward westerlies blow. Where Triton is king and his merpeople sing In mysterious fathoms below! PRINCE ERIC (spoken) Isn't this perfection, Grimsby? Out on the open sea, surrounded by nothing but water! GRIMSBY Oh, yes, it's simply... delightful. PRINCE ERIC: The salt on your skin and the wind in your hair And the waves as they ebb and they flow… We're miles from the shore and guess what, I don't care! GRIMSBY: As for me, I'm about to heave ho! ARIEL: Ah, Ah… Ah! 2 PRINCE ERIC What is that? Do you hear something? GRIMSBY Milord, please… enough seafaring! This talk of merpeople and the King of the Sea is nautical nonsense! PRINCE ERIC There it is again! Straight ahead! ARIEL: Ah… ah! GRIMSBY Your Majesty, you’ve got to return to court and take up your father’s crown! PRINCE ERIC That’s not the life for me, Grimsby. Now, follow that voice - to the ends of the Earth if we have to! PILOT Aye-aye, Captain! ALL: There's mermaids out there in the bottomless blue… An' it's hey to the starboard, heave-ho Watch out for 'em, lad, or you'll go to your ruin… In mysterious fathoms below! SCENE 2 - KING TRITON’S COURT KING TRITON 3 Benevolent Merfolk… welcome! It’s wonderful to see all of you here. -

December Trade Parade Licensed NC.Indd

LICENSED PRODUCT SCHOLASTIC DECEMBER 2018 DISCOVER THE TRUE STORY BEHIND © 2018 MARVEL JDE 8596187 Licensed Product SALES POINTS: • High-spec keepsake edition with beautiful foil cover, gilded page edges and golden ribbon. • Full retellings of Disney’s best-loved and classic stories. • Perfect for gifts. • Special non-mass market editions. • Range to be expanded in 2019, capitalising on Disney’s 2019 theatrical slate including Aladdin, Toy Story, The Lion King and Dumbo. DISNEY PIXAR: COCO DISNEY: 101 DALMATIANS DISNEY: ALICE IN CLASSIC COLLECTION CLASSIC COLLECTION WONDERLAND CLASSIC COLLECTION AU RRP: $16.99 AU RRP: $16.99 NZ RRP: $18.99 NZ RRP: $18.99 AU RRP: $16.99 Publisher: SCHOLASTIC Publisher: SCHOLASTIC NZ RRP: $18.99 AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIA Publisher: SCHOLASTIC ISBN/ABN: 9781760663988 ISBN/ABN: 9781760663995 AUSTRALIA Format: HARDBACK Format: HARDBACK ISBN/ABN: 9781760663964 Type: PICTURE Type: PICTURE Format: HARDBACK Age Level: 5+ Age Level: 5+ Type: PICTURE Dimensions: 280 X 229 MM Dimensions: 280 X 229 MM Age Level: 5+ Page Count: 72 PP Page Count: 72 PP Dimensions: 280 X 229 MM QTY QTY Page Count: 72 PP ª|xHSLHQAy663988z ª|xHSLHQAy663995z QTY ª|xHSLHQAy663964z Miguel dreams of becoming a musician, Pongo and Perdita are very proud parents just like his idol, Ernesto de la Cruz. But his to fifteen puppies. When the menacing One day, Alice chases the White Rabbit family’s generations-old ban on music means Cruella De Vil steals the puppies to make and disappears down a mysterious hole. his loved ones will never support his dream. them into a fur coat, they must leap into Follow Alice’s story as she journeys Desperate to prove his talent and gain his action! Will Pongo, Perdita and their through a mysterious land where family’s blessing, Miguel finds himself in the friends be able to find the kidnapped nothing is as it seems! extraordinary Land of the Dead.