From Inside a Prune Judas! Four May Seem Like Just Another Issue Four to You All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Dylan's Life

Bob Dylan's Life Robert Allen Zimmerman born May 24 1941 in Duluth, Minnesota known by the pseudonym of Bob Dylan, was an American singer, song-writer, musician and author. He is an influential figure in popular music and culture. He became a reluctant « voice of a generation » when he moved to New York in the 1961 where he wrote songs like « Blowin' in the Wind » and « The Times Are a-Changin’ ». Those songs were to become anthems for Civil Rights Movement and anti-war movement. His recording career goes on for more than fifty years and he explored many musical genres from folk, blues, country to gospel, rock and roll … He recorded 38 studio albums, starting with Bob Dylan (1968) and still records songs today. Dylan's lyrics contain political, social, philosophical and literary influences and over the years he defied pop music conventions. Dylan performs with guitar, keyboards and harmonica. He published his album on Columbia Records and Asylum Records. Since 1994, he also published seven books of drawings and paintings. As a musician, he sold more than 100 million records, making him one of the best-selling artists of all time. He received many awards including eleven Grammy Awards, a Golden Globe Award, an Academy Award and many other prizes such as an NME Award. Nowadays Dylan still receives huge recognition: in 2012 the President Barack Obama gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom and in 2016 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature « for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition ». -

Q Casino Announces Four Shows from This Summer's Back Waters

Contact: Abby Ferguson | Marketing Manager 563-585-3002 | [email protected] February 28, 2018 - For Immediate Release Q Casino Announces Four Shows From This Summer’s Back Waters Stage Concert Lineup! Dubuque, IA - The Back Waters Stage, Presented by American Trust, returns this summer on Schmitt Island! Q Casino is proud to announce the return of our outdoor summer experience, Back Waters Stage. This summer, both national acts and local favorites will take the stage through community events and Q Casino hosted concerts. All ages are welcome to experience the excitement at this outdoor venue. Community members can expect to enjoy a wide range of concerts from all genres from modern country to rock. The Back Waters Stage will be sponsoring two great community festivals this summer. Kickoff to Summer will be kicking off the summer series with a free show on Friday, May 25. Summer’s Last Blast 19 which is celebrating 19 years of raising money for area charities including FFA, the Boy Scouts, Dubuque County Fairgrounds and Sertoma. Summer’s Last Blast features the area’s best entertainment with free admission on Friday, August 24 and Saturday, August 25. The Back Waters Stage Summer Concert Series starts off with country rappers Colt Ford and Moonshine Bandits on Saturday, June 16. Colt Ford made an appearance in the Q Showroom last March to a sold out crowd. Ford has charted six times on the Hot Country Songs charts and co-wrote “Dirt Road Anthem,” a song later covered by Jason Aldean. On Thursday, August 9, the Back Waters Stage switches gears to modern rock with platinum recording artist, Seether. -

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

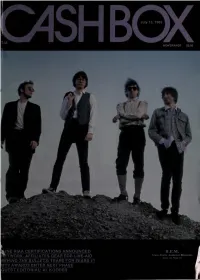

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Abandoned Love: the Impact of Wyatt V. Stickney on the Intersection

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2011 Abandoned Love: The mpI act of Wyatt .v Stickney on the Intersection between International Human Rights and Domestic Mental Disability Law Michael L. Perlin New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Disability Law Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Law & Psychology Review, Vol. 35, pp. 121-142 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. "ABANDONED LOVE": THE IMPACT OF WYATT V. STICKNEY ON THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND DOMESTIC MENTAL DISABILITY LAW Michael L. Perlin* INTRODUCTION Wyatt v. Stickney' is the most important institutional rights case liti- gated in the history of domestic mental disability law.2 It spawned copycat litigation in multiple federal district courts and state superior courts ;3 it led directly to the creation of Patients' Bills of Rights in most states;4 and it inspired the creation of the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act,' the Mental Health Systems Act Bill of Rights,6 and the federally-funded Protection and Advocacy System.7 Its direct influence on the development of the right-to-treatment doctrine abated after the Su- preme Court's disinclination, in its 1982 decision in Youngberg v. Romeo,8 to find that right to be constitutionally mandated, but its historic role as a beacon and inspiration has never truly faded. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia KOUVAROU, MARIA How to cite: KOUVAROU, MARIA (2011) `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1391/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Maria Kouvarou MA by Research in Musicology Music Department Durham University 2011 Maria Kouvarou ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Abstract Bob Dylan’s work has frequently been the object of discussion, debate and scholarly research. It has been commented on in terms of interpretation of the lyrics of his songs, of their musical treatment, and of the distinctiveness of Dylan’s performance style, while Dylan himself has been treated both as an important figure in the world of popular music, and also as an artist, as a significant poet. -

On the Road with Janis Joplin Online

6Wgt8 (Download) On the Road with Janis Joplin Online [6Wgt8.ebook] On the Road with Janis Joplin Pdf Free John Byrne Cooke *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #893672 in Books John Byrne Cooke 2015-11-03 2015-11-03Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x .93 x 5.43l, 1.00 #File Name: 0425274128448 pagesOn the Road with Janis Joplin | File size: 33.Mb John Byrne Cooke : On the Road with Janis Joplin before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised On the Road with Janis Joplin: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A Must Read!!By marieatwellI have read all but maybe 2 books on the late Janis Joplin..by far this is one of the Best I have read..it showed the "music" side of Janis,along with the "personal" side..great book..Highly Recommended,when you finish this book you feel like you've lost a band mate..and a friend..she could have accomplished so much in the studio,such as producing her own records etc..This book is excellent..0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.By Mic DAs a teen in 1969 and growing up listening to Janis and all the bands of the 60's and 70's, this book was very enjoyable to read.If you ever wondered what it might be like to be a road manager for Janis Joplin, John Byrne Cooke answers it all.Those were extra special days for all of us and John's descriptions of his experiences, helps to bring back our memories.Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

Scobie on I'm Not There

I’M NOT THERE (1956-2007) Stephen Scobie Je est un autre—Arthur Rimbaud I’m Not There (2007) In this autumn season of 2007, I can see that I am going to be thinking a lot about the Bob Dylan song known as “I’m Not There (1956).” At least, that is the title given to it on most of its early, bootleg appearances. Now that it has finally been officially released, the sub-title date has been dropped—which is a pity (since it added an element of mystery to the song) but also understandable (since no good explanation of the date has ever been given). “I’m Not There” is perhaps the ultimate Dylan bootleg, and has always been a subject for cult idealization as the most obscure of Dylan’s “lost” songs: a major master- piece that almost no one knows, and which indeed seems to conspire actively against being known. Now, it has become the title of Todd Haynes’s movie I’m Not There, “inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan”—“many” being the operative word. The film is already famous for casting six different actors to play aspects of Dylan at different points in his career. If this strategy is a gimmick, it is a successful one: the film is generating vast amounts of advance publicity, much of it based on the photographs of Cate Blanchett looking, uncannily and androgynously, like 1966 Bob. The film is not due for North American release until late November, though it has played in prestigious festivals like Toronto, New York, and Venice. -

Settin' My Dial on the Radio

SETTIN ’ MY DIAL ON THE RADIO BOB DYLAN 2006 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , NEW RELEASES , RECORDINGS & BOOKS . © 2010 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Settin’ My Dial On The Radio — Bob Dylan 2006 page 2 of 86 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................4 2 2006 AT A GLANCE ..............................................................................................................................................................4 3 THE 2006 CALENDAR ..........................................................................................................................................................4 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ..............................................................................................................................6 4.1 MODERN TIMES ................................................................................................................................................................6 4.2 BLUES ..............................................................................................................................................................................6 4.3 THEME TIME RADIO HOUR : BASEBALL ............................................................................................................................8 -

Freewheelin-On-Line Take Twenty One

Freewheelin-on-line Take Twenty One Freewheelin’ 219 This month’s cover could be the ultimate statement on the art of minimalism. Or, as Chris Cooper suggests, it could be a picture of Dylan in a snowstorm. Actually it’s neither of these. In fact, this month’s cover is meant to be a visual representation of silence which I suppose is quite natural when you consider that the journal itself concerns the comings and goings of an artist who makes a lot of noise. Before you accuse me of being a pretentious git let me plead for your sympathy and say that it wasn’t meant to be this way. I had planned a festive cover with bangles, baubles, beads and lots of angles. But then one foggy November eve some malicious spam spreader cast his spell my way and sent me an email, purporting to be from Paypal, inviting me to open an attachment. Dutifully, ignorantly and very stupidly I opened the attachment whereupon some worm leapfrogged my internet security system and crashed my pc. I tried to boot, boot boot the machine into life which only made matters worse. So I was left with no hardware, no software, no email facility and, worst of all, no access to Expecting Rain. Total silence on all fronts. I am now waiting for Santa Baby to hurry down the chimney with a brand new pc packed tight with some massive gigs and other things. Yet all I really wanna do is plug in a machine that works. So that I can hear that Windows jingle. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

2016 Estate Planning Year in Review

2016 Estate Planning Year in Review January 2017 The Answer is Blowin’ in the Wind 2016 brought a stunning, and to most, an entirely unexpected, nomination. Donald Trump? No. Bob Dylan was nominated for and received the 2016 Nobel Prize for literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Who better to launch our 2016 Estate Planning Year in Review? Contact Us Come senators, congressmen David J. Backer Please heed the call 207.253.0529 Don’t stand in the doorway [email protected] Don’t block up the hall John S. Kaminski For he that gets hurt 207.253.0561 Will be he who has stalled [email protected] There’s a battle outside And it is ragin’ Jessica M. Scherb It’ll soon shake your windows 207.253.0574 And rattle your walls [email protected] For the times they are a-changin’. David S. Sherman, Jr. - Bob Dylan, The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) 207.253.0519 [email protected] Christopher G. Stevenson th 207.253.0515 Happy 100 Birthday [email protected] Willard Scott retired a year too early to announce this one. During Rodney A. Lake 2016, the federal estate tax celebrated its centennial birthday. 207.253.0560 Although temporary estate taxes were enacted to support the Civil [email protected] and the Spanish-American Wars, the predecessor of today’s estate tax was born on September 8, 1916. When created, the estate tax Maine rate began at 1% on assets over $50,000 and topped out at 10% on 84 Marginal Way, Suite 600 assets over $5 million. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ...............................................................................................................................