Mohammad Reza Shah's Coronation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample File P’ A Karachi S T Demavend J Oun to M R Doshan Tappan Muscatto Kand Airport

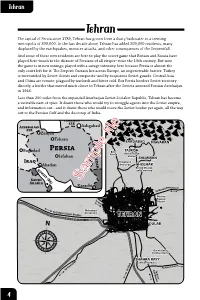

Tehran Tehran Tehran The capital of Persia since 1789, Tehran has grown from a dusty backwater to a teeming metropolis of 800,000. In the last decade alone, Tehran has added 300,000 residents, many displaced by the earthquakes, monster attacks, and other consequences of the Serpentfall. And some of these new residents are here to play the secret game that Britain and Russia have played here–much to the distaste of Persians of all stripes–since the 19th century. But now the game is in new innings; played with a savage intensity here because Persia is almost the only court left for it. The Serpent Curtain lies across Europe, an impenetrable barrier. Turkey is surrounded by Soviet clients and conquests–and by suspicious Soviet guards. Central Asia and China are remote, plagued by warlords and bitter cold. But Persia borders Soviet territory directly, a border that moved much closer to Tehran after the Soviets annexed Persian Azerbaijan in 1946. Less than 200 miles from the expanded Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, Tehran has become Tbilisia veritable nest of spies. It draws those who would try to smuggle agents into the Soviet empire, and information out…and it draws those who would move the Soviet border yet again, all the way out to the PersianBaku Gulf and the doorstep of India.Tashkent T Stalinabad SSR A Ashgabad SSR Zanjan Tehran A S KabulSAADABAD NIAVARAN Damascus Baghdad P Evin TAJRISH Prison Red Air Force Isfahan Station SHEMIRAN I Telephone Jerusalem Abadan Exchange GHOLHAK British Mission and Cemetery R S Sample file P’ A Karachi S t Demavend J oun To M R Doshan Tappan MuscatTo Kand Airport Mehrabad Jiddah To Zanjan (Soviet Border) Aerodrome BombayTEHRAN N O DULAB Gondar A A Aden S Qul’eh Gabri Parthian Ruins SHAHRA RAYY Medieval Ruins To Garm Sar Salt Desert To Hamadan To Qom To Kavir 4 Tehran Tehran THE CHARACTER OF TEHRAN Tehran sits–and increasingly, sprawls–on the southern slopes of the Elburz Mountains, specifically Mount Demavend, an extinct volcano that towers 18,000 feet above sea level. -

Interview with Bahman Jalali1

11 Interview with Bahman Jalali1 By Catherine David2 Catherine David: Among all the Muslim countries, it seems that it was in Iran where photography was first developed immediately after its invention – and was most inventive. Bahman Jalali: Yes, it arrived in Iran just eight years after its invention. Invention is one thing, what about collecting? When did collecting photographs beyond family albums begin in Iran? When did gathering, studying and curating for archives and museum exhibitions begin? When did these images gain value? And when do the first photography collections date back to? The problem in Iran is that every time a new regime is established after any political change or revolution – and it has been this way since the emperor Cyrus – it has always tried to destroy any evidence of previous rulers. The paintings in Esfahan at Chehel Sotoon3 (Forty Pillars) have five or six layers on top of each other, each person painting their own version on top of the last. In Iran, there is outrage at the previous system. Photography grew during the Qajar era until Ahmad Shah Qajar,4 and then Reza Shah5 of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah held a grudge against the Qajars and so during the Pahlavi reign anything from the Qajar era was forbidden. It is said that Reza Shah trampled over fifteen thousand glass [photographic] plates in one day at the Golestan Palace,6 shattering them all. Before the 1979 revolution, there was only one book in print by Badri Atabai, with a few photographs from the Qajar era. Every other photography book has been printed since the revolution, including the late Dr Zoka’s7 book, the Afshar book, and Semsar’s book, all printed after the revolution8. -

History Brief: Timeline of US-Iran Relations Until the Obama

MIT International Review | web.mit.edu/mitir 1 of 5 HISTORY BRIEF: TIMELINE OF US‐IRAN RELATIONS UNTIL THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION Key Facts & Catalysts By Sam Sasan Shoamanesh Looking back at key events in this US‐Iran chronicle is helpful in understanding some of the traditional causes of friction and mistrust between Tehran and Washington. A reference to the annals of US‐Iran relations will also be valuable in appreciating that the policies of the past sixty years have not been advantageous to US interests and on the contrary, have resulted in blowbacks, which still vex the relations to this day. 1856: Genesis of Formal Relations | Diplomatic relations between Iran and the United States began in 1856. 1909: American Lafayette in Iran | In 1909, Howard Baskerville, an American teacher and Princeton graduate on a Presbyterian mission in Tabriz, Iran, instantly becomes an Iranian national hero where after joining the Constitutionalists during the Constitutional Revolution of 1905‐1911, loses his young life while fighting the Royalists and the forces of the Qajar king, Mohmmad Ali Shah’s elite Cossack brigade. He is remembered as saying: ʺ[t]he only difference between me and these people is my place of birth, and this is not a big difference.ʺ To this day he is revered by Iranians. Second World War | Until the second World War, the US had no interest or an active policy vis‐à‐vis Iran and relations remained cordial. 1953 C.I.A. Coup | In 1951, Prime Minister Mossadegh and his National Front party (“Jebhe Melli”), a socio‐democratic, liberal‐secular nationalist party in Iran, nationalize the country’s oil industry. -

Iran 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

IRAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution defines the country as an Islamic republic and specifies Twelver Ja’afari Shia Islam as the official state religion. It states all laws and regulations must be based on “Islamic criteria” and an official interpretation of sharia. The constitution states citizens shall enjoy human, political, economic, and other rights, “in conformity with Islamic criteria.” The penal code specifies the death sentence for proselytizing and attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims, as well as for moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and sabb al-nabi (“insulting the Prophet”). According to the penal code, the application of the death penalty varies depending on the religion of both the perpetrator and the victim. The law prohibits Muslim citizens from changing or renouncing their religious beliefs. The constitution also stipulates five non-Ja’afari Islamic schools shall be “accorded full respect” and official status in matters of religious education and certain personal affairs. The constitution states Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians, excluding converts from Islam, are the only recognized religious minorities permitted to worship and form religious societies “within the limits of the law.” The government continued to execute individuals on charges of “enmity against God,” including two Sunni Ahwazi Arab minority prisoners at Fajr Prison on August 4. Human rights nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) continued to report the disproportionately large number of executions of Sunni prisoners, particularly Kurds, Baluchis, and Arabs. Human rights groups raised concerns regarding the use of torture, beatings in custody, forced confessions, poor prison conditions, and denials of access to legal counsel. -

British Persian Studies and the Celebrations of the 2500Th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire in 1971

British Persian Studies and the Celebrations of the 2500th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire in 1971 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. 2014 Robert Steele School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Declaration .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Copyright Statement ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives and Structure ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Statement on Primary Sources............................................................................................................................... -

King of Kings (Matthew 2)

washington,wa s h i n g t o n , dcd c KING OF KINGS Epiphany 2019 Matthew 2:1-12 Dan Claire The story of the Wise Men is the sequel to Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus, and it begins with two important details that weren’t mentioned in chapter one: namely, the place and the time. Matthew writes: “Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the east came to Jerusalem.” (2:1) The place and the time of a story usually aren’t all that exciting, but if it’s a good story, these details are often essential for understanding what the story is all about. That’s certainly the case in Matthew’s story. The place where Jesus was born, Matthew tells us, was Bethlehem–not Jerusalem. Isn’t it odd that Matthew didn’t mention this earlier, when he told the story of Jesus' birth? Matthew was saving this detail until now, until the story of the Wise Men. Most people would have expected the new king to be born in the royal palace in Jerusalem, ~5 miles to the north, and that’s exactly where the Wise Men looked first. They arrived and asked, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” (2:2) But Jesus wasn’t there. He was in the City of David, in Bethlehem and not in Jerusalem. -

C01384460 Approved for Release: 2014/02/26

C01384460 Approved for Release: 2014/02/26 APPLIND1X A . ;hose Dil? An Abbreviated History of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Dispute,-'194; -53 In 1372, the then Shah of Persia, rlaser ad-Din, in return for much needed cash, gave to Baron Paul Julius de Reuter. .'a concession to. exploit all his country's minerals (except for gold, silver, and precious stones'), all its forests and uncultivated land, and ail canals and irrigation works, as ;sell as a monopoly to construct railways and tranilways. Although the resulting uproar,-zsrac:.a11~ from neighboring Russiaraused this sweeping concession to be cancelled, de Reuter, who was a German Jew with British citizenship, persisted and by 1889 regained two parts of his original concession--the operation of a bank and the working of Persia's mines. Under the latter grant, de Reuter's men explored-for oil without great success, and the concession expired in 1999, 'the year the Baron died.` Persian oil right Shen passed to a British speculator, William Knox D'Arcy, whose first fortune had been made in Australian gold mines: The purchase price of the concession was about 50,000 pounds, and in 1903 the enterprise began to sell shares in "The First Exploitation Company." Exploratory drilling proceeded, and by 1904, two producing wells were in. a,+A - Shortly thereafter,Ainterest in oil was sharply stimulated by the efforts of Admiral Sir John Fisher, First Lord of the Admiralty, to convert the Royal Navy.from'burning coal to oil.. As a result, the Burmah Oil Company sought to become involved in eersian oil and, joining with D "lrcy and Lord Strathcona, formed the new Concessions Syndicate, L d, which endured un'ti'l 1907 when Burmah Oil bought D'Arcy out for 200„000 pounds cash and 900,000 pounds in shares. -

The Reception of European Philosophy in Qajar Iran

chapter 8 The Reception of European Philosophy in Qajar Iran Roman Seidel 1 Introduction (Historical Context) Iranian intellectual history in the Qajar era was marked by the incipient re- ception of European philosophical trends, which took place in the broader context of various processes of knowledge transmission between Europe and the Middle East. Alongside the increasing influence of European colonial- ist powers, intellectuals and scholars in the Middle East began to encounter various strands of modern Western thought. These encounters initiated new intellectual discourses, which were intended to either overcome the Islamic in- tellectual tradition or, at least, to supplement or reform Islamic thought. These discussions did not, in fact, lead to a rapid change in the philosophical dis- course in Qajar Iran and were—from the perspective of eminent philosophers of the time, as presented in this volume—a rather marginal phenomenon. Nevertheless, they added an important facet to the philosophical tradition by gradually making European philosophical doctrines accessible to Iranian scholars, a phenomenon that became especially significant in the context of the reform of the educational system. Initially, however, the Iranian interest in European thought was of a techni- cal rather than a philosophical nature. Facing the enormous military, the ad- ministrative and economic superiority of Europe, reformists, state officials and intellectuals propagated the idea that reform was needed in matters relating to the army and governmental administration.1 -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

Egyptian Policy Toward Iran and the Challenges of Transition from Break up to Normalization

JOURNAL FOR IRANIAN STUDIES Specialized Studies A Peer-Reviewed Quarterly Periodical Journal Year 1. issue 4, Sep. 2017 ISSUED BY Arabian Gulf Centre for Iranian Studies Egyptian Policy toward Iran and the Challenges of Transition from Break Up to Normalization Mo’taz Salamah (Ph.D.) Head of the Arab and Regional Studies Unit and Director of the Arabian Gulf Program at the Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies Mohammad Saied Alsayyad Intellectual and Ideological Studies Researcher in the Arabian Gulf Center for Iranian Studies espite the news and calls of some Egyptian and Iranian personalities to restore relations between the two Dcountries, no significant development has been noticed in Egypt-Iran ties for about four decades. Some observers expected that the Iranian nuclear deal in 2015 would enhance rapprochement between Cairo and Tehran, but so far, no changes have been made, nor do signs indicate a normalization of relations between the two countries.(1) Journal for Iranian Studies 41 Diplomatic ties between Egypt and Iran have been severed since the Iranian revolution in 1979, the Camp David Accords, and process of establishing peace between Egypt and Israel. These relations deteriorated primarily due to Egypt’s hosting of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi– Iran’s former monarch – despite the new Iranian leaders’ demands that Egypt hands him over for trial. In addition, the Iranian leadership adopted a hard line against Cairo by naming one of Tehran’s main streets after Khalid Islambouli, who assassinated President Sadat in 1981 – and hosting a number of Egyptian Islamic groups that escaped trial in Egypt and took refuge in Iran.(2) Iran’s practices also included inciting the Egyptian people against their regime and even hosting terrorist groups that, until recently, the Iranian media called Muslim Rebels.(3) Egypt and Iran are two key powers in the region. -

HIST 6824 Modern Iran Rome 459 Professor M.A. Atkin Wednesdays

HIST 6824 Modern Iran Rome 459 Professor M.A. Atkin Wednesdays: 5:10-7:00 Office: Phillips 340 Spring 2014 Phone: 994-6426 e-mail: [email protected] Office hours: M & W: 1:30-3:00 and and by appointment Course Description: This seminar will take a thematic approach to the period from about the year 1800 (when a state with roughly the dimensions of modern Iran emerged) to 1989 (the end of the Khomeini era.) Recurrent themes of the course include problems of state building in the context of domestic weaknesses and external pressure, ideas about reform and modernization, the impact of reform by command from above, the role of religion in politics, and major upheavals, such as the Constitutional Revolution of 1906, the oil nationalization crisis of 1951-1953, and the Islamic Revolution of 1978-1979. The specific topics and readings are listed below. The seminar meetings are structured on the basis of reading and discussion for each week’s topic. Further information on the format is in the section “Course Readings” below. In addition to the weekly reading and discussion, students are expected to write a term paper which draws on their readings for the course. The term papers are due on Monday, April 28, 2014.) Details of the paper will be provided separately. A student who already has a strong background in the history of modern Iran may prefer to focus on a research paper. Anyone who is interested in that option should inform me of that at the end of the first meeting. Early in the semester, such students should consult with me to define a suitable research project. -

IN FO R M a TIO N to U SERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced from the Microfilm Master. UMI Films the Text Directly From

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed through, substandard margin*, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Ben A Howeii Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.761-4700 800.521-0600 RENDERING TO CAESAR: SECULAR OBEDIENCE AND CONFESSIONAL LOYALTY IN MORITZ OF SAXONY'S DIPLOMACY ON THE EVE OF THE SCMALKALDIC WAR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James E.