Roaratorio” Notes Towards A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

As I Exemplify: an Examination of the Musical-Literary Relationship in the Work of John Cage LYNLEY EDMEADES

As I Exemplify: An Examination of the Musical-Literary Relationship in the Work of John Cage LYNLEY EDMEADES A thesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the ways in which John Cage negotiates the space between musical and literary compositions. It identifies and analyses the various tensions that a transposition between music and text engenders in Cage’s work, from his turn to language in the verbal score for 4’ 33’’ (1952/1961), his use of performed and performative language in the literary text “Lecture on Nothing” (1949/1959), and his attempt to “musicate” language in the later text “Empty Words” (1974–75). The thesis demonstrates the importance of the tensions that occur between music and literature in Cage’s paradoxical attempts to make works of “silence,” “nothing,” and “empty words,” and through an examination of these tensions, I argue that our experience of Cage’s work is varied and manifold. Through close attention to several performances of Cage’s work— by both himself and others—I elucidate how he mines language for its sonic possibilities, pushing it to the edge of semantic meaning, and how he turns from systems of representation in language to systems of exemplification. By attending to the structures of expectation generated by both music and literature, and how these inform our interpretation of Cage’s work, I argue for a new approach to Cage’s work that draws on contemporary affect theory. Attending to the affective dynamics and affective engagements generated by Cage’s work allows for an examination of the importance of pre-semiotic, pre-structural responses to his work and his performances. -

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

The William Paterson University Department of Music Presents New

The William Paterson University Department of Music presents New Music Series Peter Jarvis, director Featuring the Velez / Jarvis Duo, Judith Bettina & James Goldsworthy, Daniel Lippel and the William Paterson University Percussion Ensemble Monday, October 17, 2016, 7:00 PM Shea Center for the Performing Arts Program Mundus Canis (1997) George Crumb Five Humoresques for Guitar and Percussion 1. “Tammy” 2. “Fritzi” 3. “Heidel” 4. “Emma‐Jean” 5. “Yoda” Phonemena (1975) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Electronics Judith Bettina, voice Phonemena (1969) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Piano Judith Bettina, voice James Goldsworthy, Piano Penance Creek (2016) * Glen Velez For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Themes and Improvisations Peter Jarvis For open Ensemble Glen Velez & Peter Jarvis Controlled Improvisation Number 4, Opus 48 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Aria (1958) John Cage For a Voice of any Range Judith Bettina May Rain (1941) Lou Harrison For Soprano, Piano and Tam‐tam Elsa Gidlow Judith Bettina, James Goldsworthy, Peter Jarvis Ostinato Mezzo Forte, Opus 51 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Percussion Band Evan Chertok, David Endean, Greg Fredric, Jesse Gerbasi Daniel Lucci, Elise Macloon Sean Dello Monaco – Drum Set * = World Premiere Program Notes Mundus Canis: George Crumb George Crumb’s Mundus Canis came about in 1997 when he wanted to write a solo guitar piece for his friend David Starobin that would be a musical homage to the lineage of Crumb family dogs. He explains, “It occurred to me that the feline species has been disproportionately memorialized in music and I wanted to help redress the balance.” Crumb calls the work “a suite of five canis humoresques” with a character study of each dog implied through the music. -

Cage's Credo: the Discovery of New Imaginary Landscapes of Sound By

JOHN CAGE: The Works for Percussion 1 Cage’s Credo: The Discovery of Percussion Group Cincinnati New Imaginary Landscapes of Sound by Paul Cox ENGLISH 1. CREDO IN US (1942) 12:58 “It’s not a physical landscape. It’s a term discovery of new sounds. Cage found an ideal for percussion quartet (including piano and radio or phonograph. FIRST VERSION reserved for the new technologies. It’s a land- incubator for his interest in percussion and With Dimitri Shostakovich: Symphony No.5, New York Philharmonic/Leonard Bernstein scape in the future. It’s as though you used electronics at the Cornish School in Seattle, Published by DSCH-Publishers. Columbia ML 5445 (LP) technology to take you off the ground and go where he worked as composer and accompa- 2. IMAGINARY LANDSCAPE No. 5 (1952) 3:09 like Alice through the looking glass.” nist for the dance program. With access to a for any 42 recordings, score to be realized as a magnetic tape — John Cage large collection of percussion instruments and FIRST VERSION, using period jazz records. Realization by Michael Barnhart a radio studio, Cage created his first “Imagi- 3. IMAGINARY LANDSCAPE No. 4, “March No. 2” (1942) 4:26 John Cage came of age during the pioneer- nary Landscape,” a title he reserved for works for 12 radios. FIRST VERSION ing era of electronic technology in the 1920s. using electronic technology. CCM Percussion Ensemble, James Culley, conductor With new inventions improving the fidelity of The Cornish radio studio served as de facto 4. IMAGINARY LANDSCAPE No. 1 (1939) 6:52 phonographs and radios, a vast array of new music laboratory where Cage created and for 2 variable-speed turntables, frequency recordings, muted piano and cymbal, voices, sounds and music entered the American broadcast the Imaginary Landscape No. -

Cage's Early Tape Music

The Studio as a Venue for Production and Performance: Cage’s Early Tape Music Volker Straebel I When John Cage produced his Imaginary Landscape No. 5, probably the first piece of American tape music, in January 1952, he had been researching means of electronic sound production for at least twelve years. The main layer of his text The Future of Music: Credo, falsely dated 1937 in Cage’s collected lectures and writings Silence, but probably written between 1938 and 1940,1 places sound production by means of electrical instruments at the end of a development which increases the use of noise to make music, which would extend the variety of sounds available for musical purposes. The influence of Luigi Rus- solo’s L’arte dei rumori of 1913 is obvious, a manifesto that appeared in print in English translation for the first time in Nicolas Slonimsky’s Music since 1900 in 19372 and that Cage must have been aware of in 1938, when he stated in the program notes of a Percus- sion Concert presented by his ensemble in Seattle on December 9, that »percussion music really is the art of noise and that’s what it should be called.«3 In 1939, Cage created Imaginary Landscape No. 1 utilizing test-tone records played at variable speeds at the radio studio of the Cornish School in Seattle. The score, engraved and published by C. F. Peters in the early 1960s, specifies the Victor Frequency Records being used and indicates the resulting frequencies when played at 33 1/3 or 78 rpm. -

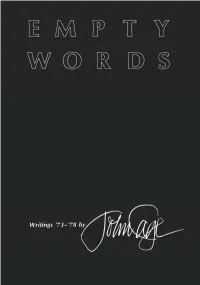

EMPTY WORDS Other

EMPTY WORDS Other Wesley an University Press books by John Cage Silence: Lectures and Writings A Year from Monday: New Lectures and Writings M: Writings '67-72 X: Writings 79-'82 MUSICAGE: CAGE MUSES on Words *Art*Music l-VI Anarchy p Writings 73-78 bv WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS Middletown, Connecticut Published by Wesleyan University Press Middletown, CT 06459 Copyright © 1973,1974,1975,1976,1977,1978,1979 by John Cage All rights reserved First paperback edition 1981 Printed in the United States of America 5 Most of the material in this volume has previously appeared elsewhere. "Preface to: 'Lecture on the Weather*" was published and copyright © 1976 by Henmar Press, Inc., 373 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10016. Reprint pernr~sion granted by the publisher. An earlier version of "How the Piano Came to be Prepared" was originally the Introduction to The Well-Prepared Piano, copyright © 1973 by Richard Bunger. Reprinted by permission of the author. Revised version copyright © 1979 by John Cage. "Empty Words" Part I copyright © 1974 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Active Anthology. Part II copyright © 1974 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Interstate 2. Part III copyright © 1975 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Big Deal Part IV copyright © 1975 by John Cage. Originally appeared in WCH WAY. "Series re Morris Graves" copyright © 1974 by John Cage. See headnote for other information. "Where are We Eating? and What are We Eating? (Thirty-eight Variations on a Theme by Alison Knowles)" from Merce Cunningham, edited and with photographs and an introduction by James Klosty. -

Imaginary Landscape -- Electronics in Live Performance, 1989 and 1939

Imaginary Landscape -- Electronics in Live Performance, 1989 and 1939 by Nicolas Collins lecture presented at Audio Arts Symposium, Linz, September 1988 Consider John Cage's Imaginary Landscape #1. Written in 1939 for two record players, test records of electronic tones, muted piano, and cymbal, it is one of the first pieces of live electronic music, and on this rests its fame. But less obvious aspects of the composition are worth noting as well. Instead of using any of the expensive electronic instruments of the time, such as the Ondes Martinot or Theremin, Cage chose the record player -- an affordable appliance, never before thought of as an "instrument," which could theoretically be played by anyone. With a prophetic eye toward alternative performance venues, the score specifically suggested that the piece be performed for "recording or broadcast." Finally, the sounds were indeed placed in a landscape, organized in a radical new way that mimicked the way sounds exist in life, rather than forcing them to "sound like some old instrument" (as Cage complained in his 1937 manifesto, The Future of Music: Credo). This intertwining of technology with its musical and social implications distinguished this piece from any other music of the time and also from any electronic music produced by other composers for over 25 years. Imaginary Landscape was truly New Music. If 1939 can be declared the birthdate of Live Electronic Music, it was a birth that was in many ways premature. As a genre it did not come of age until the late 1960's and early 1970's, with the music of Alvin Lucier, David Behrman, Robert Ashley, Gordon Mumma, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Phil Glass, Maryanne Amacher, LaMonte Young, David Tudor, and their contemporaries and students. -

Extremal Overlap-Free and Extremal Β-Free Binary Words Arxiv

Extremal overlap-free and extremal β-free binary words Lucas Mol and Narad Rampersad∗ Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Winnipeg [email protected], [email protected] Jeffrey Shallity School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo [email protected] Abstract An overlap-free (or β-free) word w over a fixed alphabet Σ is extremal if every word obtained from w by inserting a single letter from Σ at any position contains an overlap (or a factor of exponent at least β, respectively). We find all lengths which admit an extremal overlap- free binary word. For every extended real number β such that 2+ ≤ β ≤ 8=3, we show that there are arbitrarily long extremal β-free binary words. MSC 2010: 68R15 Keywords: overlap-free word; extremal overlap-free word; β-free word; extremal β-free word arXiv:2006.10152v1 [math.CO] 17 Jun 2020 1 Introduction Throughout, we use standard definitions and notations from combinatorics on words (see [11]). For every integer n ≥ 2, we let Σn denote the alphabet ∗The work of Narad Rampersad is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), [funding reference number 2019-04111]. yThe work of Jeffrey Shallit is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), [funding reference number 2018-04118]. 1 f0; 1;:::; n-1g. The word u is a factor of the word w if we can write w = xuy for some (possibly empty) words x; y.A square is a word of the form xx, where x is nonempty. -

Schuermer.Pdf —

Auditive Perspektiven 4/2012 - 1 Anna Schürmer „…es wäre ein Akt der Nächstenliebe, sie zu zerschmeißen…“ John Cage und technische Medien: Random zwischen Differenz und Wiederholung You see I don’t have a sound equipment here... zipien – abhängt, unabhängig von den gewählten I didn’t enjoy listening to records. kompositorischen Mitteln, seien sie nun technischer I was always interested in sound. oder instrumentaler Natur. Dem soll durch eine Ge- genüberstellung John Cages sprachlicher und kompo- John Cage ist ein Paradox, auch in Bezug auf seinen sitorischer Äußerungen zur technischen Reproduzier- Umgang mit technischen Medien. Einerseits positio- barkeit von Musik und dem ästhetischen Einsatz von nierte er sich wie kaum ein anderer Künstler zur Me- Medientechniken auf der einen Seite sowie seinem in- dientechnik; er reflektierte die Thematik nicht nur in strumentalen Schaffen auf der anderen Seite nachge- Vorträgen und Schriften1, sondern war treibende Kraft gangen werden. Beispielhaft wird hier das Concert for für die Entwicklung der amerikanischen Tape Music Piano and Orchestra (1958) herausgehoben, in dem und schuf mit Werken für Plattenspieler, Tonband und Cage auf keinerlei technische Medien zurückgreift und Radio zahlreiche Medien-Kompositionen2. Anderer- das dennoch Aufschluss über die hier aufgeworfenen seits können oder müssen gerade diese als kritische Fragen verspricht. Das Klavierkonzert kann als Haupt- Auseinandersetzung mit der Kunstmusik im Zeitalter werk der 1950er Jahre gelten, seit deren Beginn sich ihrer technischen Reproduzierbarkeit betrachtet wer- Cage bedingungslos dem Zufall als kompositorischem den, die Cage immer wieder mit Unbehagen kommen- Prinzip zugewendet hat. Die Aleatorik, das instrumen- tierte. Einerseits setzte Cages kompositorisches tal eingesetzten Prinzip des Random, kann als anar- Schaffen auf einfache Wiederholbarkeit, andererseits chisches Manifest und als künstlerischer Akt gegen betonte er das Ereignis der Aufführung und die Aktion technische Reproduzierung und für die Betonung des des klingenden Augenblicks. -

Nicholas Isherwood Performs John Cage

aria nicholas isherwood performs john cage nicholas isherwood BIS-2149 BIS-2149_f-b.indd 1 2014-12-03 11:19 CAGE, John (1912–92) 1 Aria (1958) with Fontana Mix (1958) 5'07 Realization of Fontana Mix by Gianluca Verlingieri (2006–09) Aria is here performed together with a new version of Fontana Mix, a multichannel tape by the Italian composer Gianluca Verlingieri, realized between 2006 and 2009 for the 50th anniversary of the original tape (1958–2008), and composed according to Cage’s indications published by Edition Peters in 1960. Verlingieri’s version, already widely performed as tape-alone piece or together with Cage’s Aria or Solo for trombone, has been revised specifically for the purpose of the present recording. 2 A Chant with Claps (?1942–43) 1'07 2 3 Sonnekus (1985) 3'42 4 Eight Whiskus (1984) 3'50 Three songs for voice and closed piano 5 A Flower (1950) 2'58 6 The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs (1942) 3'02 7 Nowth Upon Nacht (1984) 0'59 8 Experiences No. 2 (1945–48) 2'38 9 Ryoanji – version for voice and percussion (1983–85) 19'36 TT: 44'53 Nicholas Isherwood bass baritone All works published by C.F. Peters Corporation, New York; an Edition Peters Group company ere comes Cage – under his left arm, a paper bag full of recycled chance operations – in his right hand, a copy of The Book of Bosons – the new- Hfound perhaps key to matter. On his way home he stops off at his favourite natural food store and buys some dried bulgur to make a refreshing supper of tabouleh. -

![JOHN CAGE: SIXTEEN DANCES SIXTEEN DANCES (1951) JOHN CAGE 1912–1992 [1] No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0131/john-cage-sixteen-dances-sixteen-dances-1951-john-cage-1912-1992-1-no-1540131.webp)

JOHN CAGE: SIXTEEN DANCES SIXTEEN DANCES (1951) JOHN CAGE 1912–1992 [1] No

JOHN CAGE: SIXTEEN DANCES SIXTEEN DANCES (1951) JOHN CAGE 1912–1992 [1] No. 1 [Anger] 1:27 SIXTEEN DANCES [2] No. 2 [Interlude] 3:07 [3] No. 3 [Humor] 1:43 [4] No. 4 [Interlude] 2:06 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [5] No. 5 [Sorrow] 2:01 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [6] No. 6 [Interlude] 2:17 [7] No. 7 [The Heroic] 2:40 [8] No. 8 [Interlude] 3:29 [9] No. 9 [The Odious] 3:10 [10] No. 10 [Interlude] 2:20 [11] No. 11 [The Wondrous] 2:05 [12] No. 12 [Interlude] 2:09 [13] No. 13 [Fear] 1:24 [14] No. 14 [Interlude] 5:12 [15] No. 15 [The Erotic] 3:10 [16] No. 16 [Tranquility] 3:51 TOTAL 42:12 COMMENT By David Vaughan At the beginning of the 1950’s, John Cage began to use chance operations in his musical composition. He and Merce Cunningham were working on a big new piece, Sixteen Dances for Soloist and Company of Three. To facilitate the composition, Cage drew up a series of large charts on which he could plot rhythmic structures. In working with these charts, he caught first glimpse of a whole new approach to musical composition—an approach that led him very quickly to the use of chance. “Somehow,” he said, “I reached the conclusion that I could compose according to moves on these charts instead of according to my own taste.”1 The composer Christian Wolff introduced Cage to theI Ching, or Book of Changes, which COMPANY CUNNINGHAM DANCE OF MERCE COURTESY PETERICH, GERDA PHOTO: (1951).