Daniels, Simon. PUNITIVE DAMAGES Great Britain and Uncertain Ustice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economist Was a Workhorse for the Confederacy and Her Owners, the Trenholm Firms, John Fraser & Co

CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM Nassau, Bahamas (Illustrated London News Feb. 10, 1864) By Ethel Nepveux During the war, the Economist was a workhorse for the Confederacy and her owners, the Trenholm firms, John Fraser & Co. of Charleston, South Carolina, and Fraser, Trenholm & Co. of Liverpool, England, and British Nassau and Bermuda. The story of the ship comes from bits and pieces of scattered information. She first appears in Savannah, Georgia, where the Confederate network (conspiracy) used her in their efforts to obtain war materials of every kind from England. President Davis sent Captain James Bulloch to England to buy an entire navy. Davis also sent Caleb Huse to purchase armaments and send them back home. Both checked in to the Fraser, Trenholm office in Liverpool which gave them office space and the Trenholm manager Charles Prioleau furnished credit for their contracts and purchases. Neither the men nor their government had money or credit. George Trenholm (last Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederacy) bought and Prioleau loaded a ship, the Bermuda, to test the Federal blockade that had been set up to keep the South from getting supplies from abroad. They sent the ship to Savannah, Georgia, in September 1861. The trip was so successful that the Confederates bought a ship, the Fingal. Huse bought the cargo and Captain Bulloch took her himself to Savannah where he had been born and was familiar with the harbor. The ship carried the largest store of armaments that had ever crossed the ocean. Bulloch left all his monetary affairs in the hands of Fraser, Trenholm & Co. -

Officers and Crew Jack L

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar C.S.S. Alabama: An Illustrated History Library Special Collections Fall 10-10-2017 Part 2: Officers and Crew Jack L. Dickinson Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/css_al Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dickinson, Jack L., "Part 2: Officers and Crew" (2017). C.S.S. Alabama: An Illustrated History. 2. http://mds.marshall.edu/css_al/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Special Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in C.S.S. Alabama: An Illustrated History by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CSS Alabama : An Illustrated History In Six Parts: You are here Part 1: Building of Ship 290 ---> Part 2: Officers and Crew Part 3: Cruise of the Alabama Part 4: Battle with USS Kearsarge Part 5: Wreck Exploration & Excavation Part 6: Miscellaneous and Bibliography (the Alabama Claims, poems, music, sword of Raphael Semmes) To read any of the other parts, return to the menu and select that part to be downloaded. Designed and Assembled by Jack L. Dickinson Marshall University Special Collections 2017 1 CSS Alabama: An Illustrated History Officers and CREW OF THE CSS ALABAMA During the Civil War naval officers were divided into four categories for purposes of berthing and messing aboard ship: cabin, wardroom, steerage, and forward officers. The captain had a private state room, and higher ranking officers had small cabins, while lower ranks only had individual lockers. -

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

The Red Eye Series

THE RED EYE SERIES Jai Shree Ram Compiled by NARAYAN CHANGDER FOR HARDCOPY BOOK YOU CAN CONTACT NEAREST BOOKSTORE Narayan Changder I will develop this draft from time to time First printing, March 2019 Contents I Part One 1 Famous playwright, poet and others .......................... 11 1.1 John Keats.................................................... 11 1.2 Christopher Marlowe........................................... 12 1.3 Dr.Faustus By Christopher Marlowe................................ 13 1.4 John Milton................................................... 18 1.5 The Poetry of John Milton........................................ 19 1.6 Paradise Lost- John Milton....................................... 29 1.7 William Wordsworth............................................ 36 1.8 Frankenstein-Mary Shelley...................................... 37 1.9 Samuel Taylor Coleridge........................................ 38 1.10 WilliamJai Shakespeare.... Shree....................................... 39 Ram 1.11 Play by sakespear............................................. 42 1.12 Edmund Spenser.............................................. 51 1.13 Geoffrey Chaucer............................................. 52 1.14 James Joyce.................................................. 53 1.15 Dante........................................................ 63 1.16 Hamlet....................................................... 72 1.17 Macbeth...................................................... 74 1.18 Poetry....................................................... -

Blockade-Running in the Bahamas During the Civil War* by THELMA PETERS

Blockade-Running in the Bahamas During the Civil War* by THELMA PETERS T HE OPENING of the American Civil War in 1861 had the same electrifying effect on the Bahama Islands as the prince's kiss had on the Sleeping Beauty. The islands suddenly shook off their lethargy of centuries and became the clearing house for trade, intrigue, and high adventure. Nassau, long the obscurest of British colonial capi- tals, and with an ordinarily poor and indifferent population, became overnight the host to a reckless, wealthy and extravagant crowd of men from many nations and many ranks. There were newspaper correspon- dents, English navy officers on leave with half pay, underwriters, enter- tainers, adventurers, spies, crooks and bums. Out-islanders flocked to the little city to grab a share of the gold which flowed like water. One visitor reported that there were traders of so many nationalities in Nas- sau that the languages on the streets reminded one of the tongues of Babel.1 All of this transformation of a sleepy little island city of eleven thou- sand people grew out of its geographical location for it was near enough to the Confederate coast to serve as a depot to receive Southern cotton and to supply Southern war needs. England tried to maintain neutrality during the War. It is not within the scope of this paper to pass judgment on the success of her effort. Certain it is that the Bahamians made their own interpretation of British neutrality. They construed the laws of neutrality vigorously against the United States and as laxly as possible toward the South. -

Part 6: Miscellaneous and Bibliography Jack L

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar C.S.S. Alabama: An Illustrated History Library Special Collections Fall 10-11-2017 Part 6: Miscellaneous and Bibliography Jack L. Dickinson Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/css_al Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dickinson, Jack L., "Part 6: Miscellaneous and Bibliography" (2017). C.S.S. Alabama: An Illustrated History. 3. http://mds.marshall.edu/css_al/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Special Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in C.S.S. Alabama: An Illustrated History by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CSS Alabama : An Illustrated History In Six Parts: You are here Part 1: Building of Ship 290 Part 2: Officers and Crew Part 3: Cruise of the Alabama Part 4: Battle with USS Kearsarge Part 5: Wreck Exploration & Excavation ---> Part 6: Miscellaneous and Bibliography (the Alabama Claims, poems, music, sword of Raphael Semmes) To read any of the other parts, return to the menu and select that part to be downloaded. Designed and Assembled by Jack L. Dickinson Marshall University Special Collections 2017 1 CSS Alabama: An Illustrated History Miscellaneous And bibliography THE ALABAMA CLAIMS, 1862-1872 Summary from the U.S. State Department The Alabama claims were a diplomatic dispute between the United States and Great Britain that arose out of the U.S. Civil War. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in Ther 1840S and 1860S Marika Sherwood University of London

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 13 Special Double Issue "Islam & the African American Connection: Article 6 Perspectives New & Old" 1995 Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in ther 1840s and 1860s Marika Sherwood University of London Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Sherwood, Marika (1995) "Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in ther 1840s and 1860s," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 13 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol13/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sherwood: Perfidious Albion Marika Sherwood PERFIDIOUS ALBION: BRITAIN, THE USA, AND SLAVERY IN THE 1840s AND 1860s RITAI N OUTLAWED tradingin slavesin 1807;subsequentlegislation tight ened up the law, and the Royal Navy's cruisers on the West Coast B attempted to prevent the export ofany more enslaved Africans.' From 1808 through the 1860s, Britain also exerted considerable pressure (accompa nied by equally considerable sums of money) on the U.S.A., Brazil, and European countries in the trade to cease their slaving. Subsequently, at the outbreak ofthe American Civil War in 1861, which was at least partly fought over the issue ofthe extension ofslavery, Britain declared her neutrality. Insofar as appearances were concerned, the British government both engaged in a vigorous suppression of the Atlantic slave trade and kept a distance from Confederate rebels during the American Civil War. -

Marauders of the Sea, Confederate Merchant Raiders During the American Civil War

Marauders of the Sea, Confederate Merchant Raiders During the American Civil War CSS Florida. 1862-1863. Captain John Newland Maffitt. CSS Florida. 1864. Captain Charles M. Morris CSS Florida. This ship was built by William C. Miller and Sons of Liverpool, and was the first contract negotiated by Captain James Bulloch as Naval Agent of the Confederate States. She carried the dockyard name of Oreto, by March 1862, the ship was ready for sea, an English crew was signed on to sail her as an unarmed ship, this arrangement was necessary to avoid any conflict with the neutrality regulations that obtained. On the 22nd of March, she left Liverpool carrying as a passenger Master John Lowe of the Confederate States Navy, who had been ordered to deliver the ship to Captain J.N. Maffitt at Nassau. The necessary guns and equipment to fit her out for a role as an Armed Raider were shipped to that port aboard the steamer Bahama. During his total tenure in Britain, Bulloch was watched, and all his activities documented by Union people, so that as soon as Oreto arrived in Nassau, the US Consul was petitioning the British Governor to seize her as she was intended for Confederate service. He did just that twice, between April and August, but the Admiralty Court on the evidence submitted that documented her as British property, ordered the ship to be released. Back at Nassau, the intended armament for Oreto, was placed in a schooner, which then met the proposed new Raider at Green Cay, 60 miles away from Nassau on the 10th. -

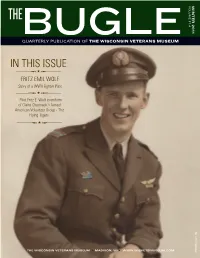

In This Issue

VOLUME 17:4 2011 WINTER IN THIS ISSUE FRITZ EMIL WOLF Story of a WWII Fighter Pilot Pilot Fritz E. Wolf in uniform of Claire Chennault’s famed American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers. THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM WVM Mss 2011.102 FROM THE DIRECTOR Wisconsin Veterans Museum. How soldier in the 7th Wisconsin. He may could it be otherwise? We are sur- have read about the Iron Brigade rounded by things that resonate in books, but the idea of advancing with stories of Wisconsin’s veterans. shoulder to shoulder in line of battle In this issue you will read stories under musket and cannon fire was about three men who, although sep- a relic of a far away past. Likewise, arated by time, embody commonly Hunt could never have imagined held traits that link them together Wolf’s airplane, let alone land- among a long line of veterans. We ing one on the deck of a ship. As a start with the account of the in- resident of Kenosha, Isermann may trepid naval combat flying ace Fritz have known veterans of Hunt’s Iron Wolf, a native of Madison by way of Brigade, but their ancient exploits Shawano, Wisconsin who flew with were long ago events separated by Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in more than fifty years from the Great China, and later with the US Navy. War. To a twentieth century man Wolf’s story is followed by the tragic engaged in WWI naval operations, account of an English immigrant, Gettysburg might as well have been John Hunt, who settled in Wiscon- Thermopylae. -

Autographs – Auction November 8, 2018 at 1:30Pm 1

Autographs – Auction November 8, 2018 at 1:30pm 1 (AMERICAN REVOLUTION.) CHARLES LEE. Brief Letter Signed, as Secretary 1 to the Board of Treasury, to Commissioner of the Continental Loan Office for the State of Massachusetts Bay Nathaniel Appleton, sending "the Resolution of the Congress for the Renewal of lost or destroyed Certificates, and a form of the Bond required to be taken on every such Occasion" [not present]. ½ page, tall 4to; moderate toning at edges and horizontal folds. Philadelphia, 16 June 1780 [300/400] Charles Lee (1758-1815) held the post of Secretary to the Board of Treasury during 1780 before beginning law practice in Virginia; he served as U.S. Attorney General, 1795-1801. From the Collection of William Wheeler III. (AMERICAN REVOLUTION.) WILLIAM WILLIAMS. 2 Autograph Document Signed, "Wm Williams Treas'r," ordering Mr. David Lathrop to pay £5.16.6 to John Clark. 4x7½ inches; ink cancellation through signature, minor scattered staining, folds, docketing on verso. Lebanon, 20 May 1782 [200/300] William Williams (1731-1811) was a signer from CT who twice paid for expeditions of the Continental Army out of his own pocket; he was a selectman, and, between 1752 and 1796, both town clerk and town treasurer of Lebanon. (AMERICAN REVOLUTION--AMERICAN SOLDIERS.) Group of 8 items 3 Signed, or Signed and Inscribed. Format and condition vary. Vp, 1774-1805 [800/1,200] Henry Knox. Document Signed, "HKnox," selling his sloop Quick Lime to Edward Thillman. 2 pages, tall 4to, with integral blank. Np, 24 May 1805 * John Chester (2). ALsS, as Supervisor of the Revenue, to Collector White, sending [revenue] stamps and home distillery certificates [not present]. -

OONGRES Lon AL S RECORD-HOUSE

1918 •. L~ . , OONGRES lON AL s RECORD-HOUSE. Senate Clwmber, pair d and not voting, the Chair declares the important to determine weights and measures for the District conference report agreed to. of Columbia than to pas the Army bill, I shall not object. ~Jr. 1.\IcKE~ZIE. -1\Ir. Speaker, reserving the right to object, . AD.TOURNME::.\"T. I thoughf we had an understanding that bills corning from the l\Ir. 1.\IAR~IN. I move that the Senate adjourn. Committee on 1\Iilitm·y Affairs, except on speciaL days, should The motion was agreed to; and (at 4 o'clock and 35 minutes have the right of way. Now, if the request of the gentleman p. m.) the Senate adjourned until to-morrow, Tuesday, :llay 28, from Kentucky is C{)n ented to, why of course it wiD. make u 1018, at 12 o'clock meridian. special day for the consideration of his bills and cut out consid et·atlon of the. military app1.·opriati.on bill, which ought to be con sidered without a moment's delay. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Mr. KITCHL.~. Mr. Speaker, I hope the gentl€man from Ken tucky will '\'\'ithdraw his request now, and that he ~ll make it ~-!O:NDAY, l1fay ~7, 1918. follo·wing the pill age of the military appropriation bill. The House met at 12 o'clock noon. 1\Ir. JO~SO~ of Kerrtueky. 1\.Ir. Speaker, I will modify the The Chaplain, Rev. Henry N. Couden, D. D., offe ed the fol request-- lowing prayer : 1.\:Ir. KI~Clill:N.