TOCC0458DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Profile

PROPOSAL PIANO RECITAL, WORKSHOP and/or LECTURE CLARE HAMMOND, piano SAMPLE PROGRAMME 1 SAMPLE PROGRAMME 2 DEBUSSY COUPERIN Estampes (12’) Selection from Pièces de Clavecin, 6e ordre (8’) MENDELSSOHN WOOLRICH Andante and Rondo Capriccioso (6’) Pianobook IX (10’) BEETHOVEN RAVEL Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13 ‘Pathétique’ (22’) Le Tombeau de Couperin (25’) INTERVAL INTERVAL LYAPUNOV Three Études d’Exécution Transcendante (16’) RAVEL Sonatine (12’) CHOPIN Selection from Études, Op. 25 (18’) SIMAKU Hommage à Kurtag (6’) KAPUSTIN Three Studies in Different Intervals (9’) RACHMANINOV Variations on a Corelli Theme, Op. 42 (20’) Listen to audio demos of Lyapunov and Kapustin at: www.clarehammond.com/etude.html SAMPLE WORKSHOPS ACADEMIC LECTURE as an example of practice-based research Performance classes with instrumentalists (Includes demonstrations at the piano) and vocalists Creative responses to disability and the Individual coaching for pianists performer's prerogative in Benjamin Britten's Diversions, op. 21 Composition workshops on writing for the piano, with undergraduate and postgraduate The pianist Paul Wittgenstein lost his right arm during the students First World War and subsequently commissioned a large number of piano works, solo, chamber and concerto, for Chamber coaching for ensembles the left hand. In 1940 he asked Benjamin Britten to compose a left-hand piano concerto, Diversions, op. 21. Individual academic supervisions with Britten was initially enthusiastic but the genesis of the students working within Performance work was marred by disagreements between composer Studies, on nineteenth- and twentieth- and performer concerning scoring and structure. century pianism, on virtuosity, or on the Wittgenstein's score of Diversions is littered with relationship between performer and embellishments, modifications and recomposed passages composer. -

Download Booklet

a song more silent new works for remembrance Sally Beamish | Cecilia McDowall Tarik O’Regan | Lynne Plowman Portsmouth Grammar School Chamber Choir London Mozart Players Nicolae Moldoveanu It was J. B. Priestley who first drew attention Hundreds of young people are given the to the apparent contradiction on British war opportunity to participate as writers, readers, memorials: the stony assertion that ‘Their Name singers and instrumentalists, working in Liveth for Evermore’ qualified by the caution collaboration with some of our leading ‘Lest We Forget’. composers to create works that are both thoughtful and challenging in response to ideas It is a tension which reminds us of the need for of peace and war. each generation to remember the past and to express its own commitment to a vision of peace. E. E. Cummings’ poem these children singing in stone, set so evocatively by Lynne Plowman, The pupils of Portsmouth Grammar School are offers a vision of “children forever singing” as uniquely placed to experience this. The school images of stone and blossom intertwine. These is located in 19th-century barracks at the heart new works for Remembrance are an expression of a Garrison City, once the location of Richard of hope from a younger generation moved and the Lionheart’s palace. Soldiers have been sent inspired by “a song more silent”. around the world from this site for centuries. It has been suggested that more pupils lost their James Priory Headmaster 2008 lives in the two World Wars than at any other school of comparable size. Today, as an inscription on the school archway celebrates, it is a place where girls and boys come to learn and play. -

Currier Time Machines

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited October 2011 2011/3 Currier Time Machines Britten Included in this issue: Sebastian Currier’s concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter, notes from an opening movement, eschews what Pagodas in MacMillan is obvious, and goes straight toward a quantum Clemency staged at premiered by the New York Philharmonic in June, was leap of space and time… Like the finest of modern The Royal Opera in London recently released by DG and travels to Europe in January. painters, Mr. Currier has a variety of counterpoints Japan in the background, instruments enjoying their own dialogues and intriguing conversations, as Ms. Benjamin Britten’s only ballet, The Prince of Mutter plunged ahead.” ConcertoNet the Pagodas, travels back to its roots in the Currier’s harp concerto, Traces, received its Far East this autumn with its first Japanese US premiere at the Grand Teton Festival in staging. The new choreography by David July with soloist Naoko Yoshino and Bintley is unveiled on 30 October at the New conductor Osmo Vänskä. The work was National Theatre in Tokyo with Paul Murphy composed for Marie-Pierre Langlamet and conducting the Tokyo Philharmonic premiered in 2009 by the Berliner Orchestra. The staging is a co-production Philharmoniker and Donald Runnicles. with Birmingham Royal Ballet, who will present the ballet in the UK in January/ Next Atlantis, combining strings (quartet or February 2014 as one of the closing orchestral), electronics and video by Pawel highlights of the Britten centenary (2013). Wojtaski, receives performances in Miami David Bintley’s choreography of The Prince Dean and New York this autumn. -

Opera & Ballet 2017

12mm spine THE MUSIC SALES GROUP A CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR THE STAGE ALPHONSE LEDUC ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS BOSWORTH CHESTER MUSIC OPERA / MUSICSALES BALLET OPERA/BALLET EDITION WILHELM HANSEN NOVELLO & COMPANY G.SCHIRMER UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES NEW CAT08195 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC SALES GROUP EDITION CAT08195 Opera/Ballet Cover.indd All Pages 13/04/2017 11:01 MUSICSALES CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 1 1 12/04/2017 13:09 Hans Abrahamsen Mark Adamo John Adams John Luther Adams Louise Alenius Boserup George Antheil Craig Armstrong Malcolm Arnold Matthew Aucoin Samuel Barber Jeff Beal Iain Bell Richard Rodney Bennett Lennox Berkeley Arthur Bliss Ernest Bloch Anders Brødsgaard Peter Bruun Geoffrey Burgon Britta Byström Benet Casablancas Elliott Carter Daniel Catán Carlos Chávez Stewart Copeland John Corigliano Henry Cowell MUSICSALES Richard Danielpour Donnacha Dennehy Bryce Dessner Avner Dorman Søren Nils Eichberg Ludovico Einaudi Brian Elias Duke Ellington Manuel de Falla Gabriela Lena Frank Philip Glass Michael Gordon Henryk Mikolaj Górecki Morton Gould José Luis Greco Jorge Grundman Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Albert Guinovart Haflidi Hallgrímsson John Harbison Henrik Hellstenius Hans Werner Henze Juliana Hodkinson Bo Holten Arthur Honegger Karel Husa Jacques Ibert Angel Illarramendi Aaron Jay Kernis CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 2 12/04/2017 13:09 2 Leon Kirchner Anders Koppel Ezra Laderman David Lang Rued Langgaard Peter Lieberson Bent Lorentzen Witold Lutosławski Missy Mazzoli Niels Marthinsen Peter Maxwell Davies John McCabe Gian Carlo Menotti Olivier Messiaen Darius Milhaud Nico Muhly Thea Musgrave Carl Nielsen Arne Nordheim Per Nørgård Michael Nyman Tarik O’Regan Andy Pape Ramon Paus Anthony Payne Jocelyn Pook Francis Poulenc OPERA/BALLET André Previn Karl Aage Rasmussen Sunleif Rasmussen Robin Rimbaud (Scanner) Robert X. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 108, 1988-1989

'"'"• —— M« QUADRUM The Mall At Chestnut Hill 617-965-5555 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Carl St. Clair and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Eighth Season, 1988-89 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman George H. Kidder, President J.P. Barger, Yice-Chairman Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. Robert B. Newman David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick Peter C. Read Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Avram J. Goldberg Richard A. Smith James F. Cleary Mrs. John L. Grandin Ray Stata Julian Cohen Francis W. Hatch, Jr. William F. Thompson William M. Crozier, Jr. Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Mrs. Michael H. Davis Mrs. August R. Meyer Trustees Emeriti Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. George R. Rowland Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Mrs. George Lee Sargent Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson Sidney Stoneman Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey Abram T. Collier Irving W. Rabb John L. Thorndike Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Jay B. Wailes, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Kenneth Haas, Managing Director Daniel R. Gustin, Assistant Managing Director and Manager of Tanglewood Michael G. McDonough, Director of Finance and Business Affairs Anne H. Parsons, Orchestra Manager Costa Pilavachi, Artistic Administrator Caroline Smedvig, Director of Promotion Josiah Stevenson, Director of Development Robert Bell, Data Processing Manager Marc Mandel, Publications Coordinator Helen P. -

Department of Music

Robert SAXTON (b. 1953) www.uymp.co.uk also taught alongside Leonard Bernstein. He was assistant to Sir Peter Maxwell Davies at Dartington Summer School (1983-84) and on Hoy in the 1990s. During the 1980s and 1990s, Saxton also undertook outreach education work both with Glyndebourne Opera and Opera North in the UK, and in Norway and Japan with the London Sinfonietta. Following a post as a lecturer at Bristol University, Saxton was Head of Composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama (1991-98), Head of Composition and Contemporary Music at the Royal Academy of Music (1998-99) and, since 1999, has been at Oxford University, where he is Professor of Composition and Tutorial Fellow in Music at Worcester College. Having been a member of the Arts Council Music Panel, he was from 1997- 2007 a Board member of London's Southbank Centre. From 1992-98 Saxton was Artistic Director of Opera Lab and from 2011-12 was Composition Mentor for Sounds New, a joint Anglo-French/EU project. Robert is Composer- Photo by Katie Vandyck in-Association at the Purcell School. Robert Saxton was born in London in 1953. He Selected commissions include works for the BBC began composing aged 6 and, after early advice (TV, Radio 3 and the Proms), ECO, LPO, LSO, from Benjamin Britten, he studied with London Sinfonietta, Nash Ensemble, Northern Elisabeth Lutyens (1970-74), at Cambridge Sinfonia, St Paul Chamber Orchestra USA, (1972-75) where he received composition tuition Christ Church Cathedral Oxford, Chilingirian from Robin Holloway and as a postgraduate at String Quartet, The Clerks, Aldeburgh, Oxford with Robert Sherlaw Johnson (1975-76), Cheltenham, City of London, Huddersfield and where he had composition lessons with Luciano Lichfield festivals, and for Richard Rodney Berio. -

British and Commonwealth Symphonies from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH SYMPHONIES FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KATY ABBOTT (b. 1971) She studied composition with Brenton Broadstock and Linda Kouvaras at the University of Melbourne where she received her Masters and PhD. In addition to composing, she teaches post-graduate composition as an onorary Fellow at University of Melbourne.Her body of work includes orchestral, chamber and vocal pieces. A Wind Symphony, Jumeirah Jane was written in 2008. Symphony No. 1 "Souls of Fire" (2004) Robert Ian Winstin//Kiev Philharmonic Orchestra (included in collection: "Masterworks of the New Era- Volume 12") ERM MEDIA 6827 (4 CDs) (2008) MURRAY ADASKIN (1905-2002) Born in Toronto. After extensive training on the violin he studied composition with John Weinzweig, Darius Milhaud and Charles Jones. He taught at the University of Saskatchewan where he was also composer-in-residence. His musical output was extensive ranging from opera to solo instrument pieces. He wrote an Algonquin Symphony in 1958, a Concerto for Orchestra and other works for orchestra. Algonquin Symphony (1958) Victor Feldbrill/Toronto Symphony Orchestra ( + G. Ridout: Fall Fair, Champagne: Damse Villageoise, K. Jomes: The Jones Boys from "Mirimachi Ballad", Chotem: North Country, Weinzweig: Barn Dance from "Red Ear of Corn" and E. Macmillan: À Saint-Malo) CITADEL CT-601 (LP) (1976) Ballet Symphony (1951) Geoffrey Waddington/Toronto Symphony Orchestra (included in collection: “Anthology Of Canadian Music – Murray Adaskin”) RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL ACM 23 (5 CDs) (1986) (original LP release: RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL RCI 71 (1950s) THOMAS ADÈS (b. -

Download Booklet

PSALM PSALM three new stunning trumpet concertos written for CONTEMPORARY BRITISH TRUMPET CONCERTOS Contemporary British Trumpet Concertos me by three of Britain’s finest composers. From its inception, this recording has been Deborah Pritchard’s Skyspace is one of the first Skyspace (2012) Deborah Pritchard (b. 1977) entwined with my graduate studies. Fresh from modern concertos to be conceived solely for 1 I. Aurum [1.18] the Royal College of Music in 2007, I matriculated piccolo trumpet. Though a popular instrument, 2 II. Aurum Resonance [1.24] at the University of Oxford to begin a doctoral it has thus far been surprisingly restricted 3 III. Light Iridescent [0.50] thesis in musicology. During this time I to concerto performances of earlier baroque 4 IV. Opaque [0.49] encountered the music of Oxford professor concertos and transcriptions. This is despite its 5 V. Opaque Resonance [2.04] 6 VI. Dark Iridescent [1.07] Robert Saxton, who, it transpired, had written wonderful treatment in the symphony orchestra: 7 VII. Cerulean [2.22] a trumpet concerto Psalm: A Song of Ascents Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphony or Britten’s in 1992. At this formative stage of my career, Four Sea Interludes, for example. Deborah’s 8 Psalm: A Song of Ascents (1992) Robert Saxton (b. 1953) [15.45] I was determined that I wanted to combine music maintains vivid and direct relationships solo performance with academia, and the with visual and conceptual art, placing her La Primavera (2012) John McCabe (b. 1939) 9 I. Allegro [5.23] opportunity to bring British music to life work within a fascinating, rich interdisciplinary 0 II. -

PROGRAMME: SATURDAY 19 JUNE Joseph Middleton Director Jane Anthony Founder

PROGRAMME: SATURDAY 19 JUNE Joseph Middleton Director Jane Anthony Founder leedslieder1 @LeedsLieder @leedsliederfestival #LLF21 Welcome to The Leeds Lieder 2021 Festival Ten Festivals and a Pandemic! In 2004 a group of passionate, visionary song enthusiasts began programming recitals in Leeds and this venture has steadily grown to become the jam-packed season we now enjoy. With multiple artistic partners and thousands of individuals attending our events every year, Leeds Lieder is a true cultural success story. 2020 Elly Ameling was certainly a year of reacting nimbly and working in new paradigms. Joseph Middleton Joseph We turned Leeds Lieder into its own broadcaster and went digital. It has Director, Leeds Lieder Director, been extremely rewarding to connect with audiences all over the world Leeds Lieder President, throughout the past 12 months, and to support artists both internationally known and just starting out. The support of our Friends and the generosity shown by our audiences has meant that we have been able to continue our award-winning education programmes online, commission new works and provide valuable training for young artists. In 2021 we have invited more musicians than ever before to appear in our Festival and for the first time we look forward to being hosted by Leeds Town Hall. The art of the A message from Elly Ameling, song recital continues to be relevant and flourish in Yorkshire. Hon. President of Leeds Lieder As the finest Festival of art song in the North, we continue to provide a platform for international stars to rub shoulders with the next generation As long as I have been in joyful contact with Leeds Lieder, from 2005 until of emerging musicians. -

Download the World Premiere Programme

EMILY PROGRAMME PRODUCTION SPONSORS PRS for Music Foundation is the UK’s leading funder of new music across all genres. Since 2000 PRS for Music Foundation has given more than £14 million to over 4,000 new music initiatives by awarding grants and leading partnership programmes that support music sector development. Widely respected as an adventurous and proactive funding body, PRS for Music Foundation supports an exceptional range of new music activity– from composer residencies and commissions to festivals and showcases in the UK and overseas. http://www.prsformusicfoundation.com The RVW Trust was established in 1956 by Ralph Vaughan Williams. He had always been a generous personal supporter of many musical and charitable purposes and he wanted to ensure that this support could continue after his death. With the wholehearted support of his wife Ursula this charitable trust was established whereby the income from the Performing Rights in his music could be directed towards the purposes which he held dear. In 1997 the constitution of the trust was brought up to date whilst its original purposes were maintained unchanged and it continues to honour the intentions and memory of the Founder. The trust has an active board of trustees of which the current chairman is Hugh Cobbe, OBE, FSA. The trustees are supported by a group of specialist music advisers. http://www.rvwtrust.org.uk The Mayor of Todmorden, Cllr Jayne Booth, will attend the world première of Emily on 4th July. http://www.todmordencouncil.org.uk EMILY Opera in two acts by Tim Benjamin -

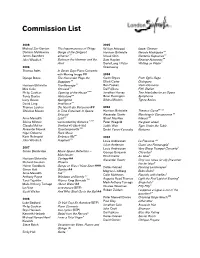

Commission List

Commission List 2009 2005 Michael Zev Gordon The Impermanence of Things William Attwood Iwwer Tiermen Dominic Muldowney Songs of the Zeitgeist Harrison Birtwistle Neruda Madrigales** James Saunders either/or BTP Unsuk Chin Cantatrix Sopranica CC John Woolrich cc Between the Hammer and the Sam Hayden Relative Autonomy CC Anvil David Lang / Peter Writing on Water L 2008 Greenaway Thomas Adès In Seven Days Piano Concerto with Moving Image ## 2004 Django Bates The Corncrake Plays the Gavin Bryars From Egil’s Saga Bagpipes SS Elliott Carter Dialogues Harrison Birtwistle The Message SS Ben Foskett Violin Concerto Mira Calix Ort-oard SS Dai Fujikura Fifth Station Philip Cashian Opening of the House KPMF Jonathan Harvey Two Interludes for an Opera Tansy Davies Hinterland ** Brian Herrington Symphonia Larry Goves Springtime Silvina Milstein Tigres Azules David Lang lend/lease SS Thomas Larcher Die Nacht der Verlorenen## 2003 Christian Mason In Time Entwined, In Space Harrison Birtwistle Theseus Game CC ** Enlaced Alexander Goehr Marching to Carcassonne ** Anna Meredith Lylat SS Stuart MacRae Interact CC Silvina Milstein surrounded by distance ACEST Peter Wiegold the great wheel Claudia Molitor Untitled 40 [desk-life] Judith Weir Tiger Under the Table Alexander Nowak Quantemporette KMA Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky Notturno Nigel Osborne Rock Music CC Karin Rehnqvist Embrace Me 2002 SS John Woolrich Fragment Louis Andriessen La Passione ** Julian Anderson Quasi una Passacaglia L 2007 Louis Andriessen Very Sharp Trumpet Concerto L Simon Bainbridge Music -

St Catharine's College, Cambridge 2015

ST CATHARINE’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE 2015 ST CATHARINE’S MAGAZINE 2015 St Catharine’s College, Cambridge CB2 1RL Published by the St Catharine’s College Society. Porters’ Lodge/switchboard: !"##$ $$% $!! © #!"' The Master and Fellows of St Catharine’s College, Fax: !"##$ $$% $&! Cambridge. College website: www.caths.cam.ac.uk Society website: www.caths.cam.ac.uk/society – Printed in England by Langham Press some details are only accessible to registered members (www.langhampress.co.uk) on (see www.caths.cam.ac.uk/society/register) elemental-chlorine-free paper from Branch activities: www.caths.cam.ac.uk/society/branches sustainable forests. TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial .................................................................................& Society Report Society Committee #!"'–"( .........................................*# College Report The Society President ....................................................*# Master’s report ...................................................................% Report of %*th Annual General Meeting .................*$ The Fellowship.................................................................."& Accounts for the year to $! June #!"' ...................... ** New Fellows ......................................................................"( Society Awards .................................................................*% Retirements and Farewells ...........................................") Society Presidents’ Dinner ............................................*) Professor Sir Christopher