Bisphosphonate Guidelines for Treatment and Prevention Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nitrate Prodrugs Able to Release Nitric Oxide in a Controlled and Selective

Europäisches Patentamt *EP001336602A1* (19) European Patent Office Office européen des brevets (11) EP 1 336 602 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.7: C07C 205/00, A61K 31/00 20.08.2003 Bulletin 2003/34 (21) Application number: 02425075.5 (22) Date of filing: 13.02.2002 (84) Designated Contracting States: (71) Applicant: Scaramuzzino, Giovanni AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU 20052 Monza (Milano) (IT) MC NL PT SE TR Designated Extension States: (72) Inventor: Scaramuzzino, Giovanni AL LT LV MK RO SI 20052 Monza (Milano) (IT) (54) Nitrate prodrugs able to release nitric oxide in a controlled and selective way and their use for prevention and treatment of inflammatory, ischemic and proliferative diseases (57) New pharmaceutical compounds of general effects and for this reason they are useful for the prep- formula (I): F-(X)q where q is an integer from 1 to 5, pref- aration of medicines for prevention and treatment of in- erably 1; -F is chosen among drugs described in the text, flammatory, ischemic, degenerative and proliferative -X is chosen among 4 groups -M, -T, -V and -Y as de- diseases of musculoskeletal, tegumental, respiratory, scribed in the text. gastrointestinal, genito-urinary and central nervous sys- The compounds of general formula (I) are nitrate tems. prodrugs which can release nitric oxide in vivo in a con- trolled and selective way and without hypotensive side EP 1 336 602 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 1 336 602 A1 Description [0001] The present invention relates to new nitrate prodrugs which can release nitric oxide in vivo in a controlled and selective way and without the side effects typical of nitrate vasodilators drugs. -

Protocol Supplementary

Optimal Pharmacological Management and Prevention of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis (GIOP) Protocol for a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis Supplementary Materials: Sample Search Strategy Supplementary 1: MEDLINE Search Strategy Database: OVID Medline Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present Line 1 exp Osteoporosis/ 2 osteoporos?s.ti,ab,kf. 3 Bone Diseases, Metabolic/ 4 osteop?eni*.ti,ab,kf. 5 Bone Diseases/ 6 exp Bone Resorption/ 7 malabsorption.ti,ab,kf. 8 Bone Density/ 9 BMD.ti,ab,kf. 10 exp Fractures, Bone/ 11 fracture*.ti,ab,kf. 12 (bone* adj2 (loss* or disease* or resorption* or densit* or content* or fragil* or mass* or demineral* or decalcif* or calcif* or strength*)).ti,ab,kf. 13 osteomalacia.ti,ab,kf. 14 or/1-13 15 exp Glucocorticoids/ 16 exp Steroids/ 17 (glucocorticoid* or steroid* or prednisone or prednisolone or hydrocortisone or cortisone or triamcinolone or dexamethasone or betamethasone or methylprednisolone).ti,ab,kf. 18 or/15-17 19 14 and 18 20 ((glucocorticoid-induced or glucosteroid-induced or corticosteroid-induced or glucocorticosteroid-induced) adj1 osteoporos?s).ti,ab,kf. 21 19 or 20 22 exp Diphosphonates/ 23 (bisphosphon* or diphosphon*).ti,ab,kf. 24 exp organophosphates/ or organophosphonates/ 25 (organophosphate* or organophosphonate*).ti,ab,kf. 26 (alendronate or alendronic acid or Fosamax or Binosto or Denfos or Fosagen or Lendrate).ti,ab,kf. 27 (Densidron or Adrovance or Alenotop or Alned or Dronat or Durost or Fixopan or Forosa or Fosval or Huesobone or Ostemax or Oseolen or Arendal or Beenos or Berlex or Fosalen or Fosmin or Fostolin or Fosavance).ti,ab,kf. -

Date Database Search Strategy Filters Results Results After Duplicates

Date Database Search Strategy Filters Results Results after Duplicates Removed 12/12/2018 PubMed (("Patient Participation"[Mesh] OR "Patient Participation" OR “Patient Filters: 120 108 Involvement” OR “Patient Empowerment” OR “Patient Participation Rates” English OR “Patient Participation Rate” OR “Patient Activation” OR “Patient Engagement” OR "Refusal to Participate"[Mesh] OR "Refusal to Participate" OR "Self Care"[Mesh] OR "Self Care" OR "Self-Care" OR “Well-being” OR Wellbeing OR “well being” OR "Walking"[Mesh] OR Walking OR Walk OR Walked OR Ambulation OR "Gait"[Mesh] OR Gait OR Gaits OR "Mobility Limitation"[Mesh] OR "Mobility Limitation" OR Mobility OR “Mobility Limitations” OR “Ambulation Difficulty” OR “Ambulation Difficulties” OR “Difficulty Ambulation” OR “Ambulatory Difficulty” OR “Ambulatory Difficulties” OR “Difficulty Walking” OR "Dependent Ambulation"[Mesh] OR "Dependent Ambulation" OR “functional status” OR “functional state” OR "Community Participation"[Mesh] OR "Community Participation" OR “Community Involvement” OR “Community Involvements” OR “Consumer Participation” OR “Consumer Involvement” OR “Public Participation” OR “Community Action” OR “Community Actions” OR "Social Participation"[Mesh] OR "Social Participation" OR "Activities of Daily Living"[Mesh] OR "Activities of Daily Living" OR ADL OR “Daily Living Activities” OR “Daily Living Activity” OR “Chronic Limitation of Activity” OR "Quality of Life"[Mesh] OR "Quality of Life" OR “Life Quality” OR “Health- Related Quality Of Life” OR “Health Related Quality Of -

Bisphosphonates Can Be Safely Given to Patients with Hypercalcemia And

Clinical Research in Practice: The Journal of Team Hippocrates Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 11 2019 Bisphosphonates can be safely given to patients with hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency secondary to multiple myeloma Matthew .J Miller Wayne State University School of Medicine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/crp Part of the Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism Commons, Medical Education Commons, Nephrology Commons, and the Translational Medical Research Commons Recommended Citation MILLER MJ. Bisphosphonates can be safely given to patients with hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency secondary to multiple myeloma. Clin. Res. Prac. 2019 Mar 14;5(1):eP1846. doi: 10.22237/crp/1552521660 This Critical Analysis is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Clinical Research in Practice: The ourJ nal of Team Hippocrates by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. VOL 5 ISS 1 / eP1846 / MARCH 14, 2019 doi: 10.22237/crp/1552521660 Bisphosphonates can be safely given to patients with hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency secondary to multiple myeloma MATTHEW J. MILLER, B.S., Wayne State University School of Medicine, [email protected] ABSTRACT A critical appraisal and clinical application of Itou K, Fukuyama T, Sasabuchi Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of oral rehydration therapy until 2 h before surgery: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anesthesia. 2012;26(1):20-27. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1261-x. Keywords: bisphosphonates, nephrotoxicity, safety, renal insufficiency, renal failure, multiple myeloma, pamidronate, ibandronate, zaledronic acid Clinical Context An 83-year-old African-American female with a history of multiple vertebral compression fractures and gastritis presented for the second time in two weeks with symptoms of hypercalcemia. -

RANKL Acts Directly on RANK-Expressing Prostate Tumor Cells and Mediates Migration and Expression of Tumor Metastasis Genes

TheProstate68:92^104(2008) RANKL Acts Directly on RANK-Expressing Prostate Tumor Cells and Mediates Migration and Expression of Tumor Metastasis Genes Allison P. Armstrong,1 Robert E. Miller,1 Jon C. Jones,1 Jian Zhang,2 Evan T. Keller,2 and William C. Dougall1* 1Departments of Hematology/Oncology Research, Amgen Inc., Seattle,Washington 2University of Michigan, Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, Michigan BACKGROUND. Metastases to bone are a frequent complication of human prostate cancer and result in the development of osteoblastic lesions that include an underlying osteoclastic component. Previous studies in rodent models of breast and prostate cancer have established that receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL) inhibition decreases bone lesion development and tumor growth in bone. RANK is essential for osteoclast differentiation, activation, and survival via its expression on osteoclasts and their precursors. RANK expression has also been observed in some tumor cell types such as breast and colon, suggesting that RANKL may play a direct role on tumor cells. METHODS. Male CB17 severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice were injected with PC3 cells intratibially and treated with either PBS or human osteprotegerin (OPG)-Fc, a RANKL antagonist. The formation of osteolytic lesions was analyzed by X-ray, and local and systemic levels of RANKL and OPG were analyzed. RANK mRNA and protein expression were assessed on multiple prostate cancer cell lines, and events downstream of RANK activation were studied in PC3 cells in vitro. RESULTS. OPG-Fc treatment of PC3 tumor-bearing mice decreased lesion formation and tumor burden. Systemic and local levels of RANKL expression were increased in PC3 tumor bearing mice. -

Phvwp Class Review Bisphosphonates and Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (Alendronic Acid, Clodronic Acid, Etidronic Acid, Ibandronic

PhVWP Class Review Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw (alendronic acid, clodronic acid, etidronic acid, ibandronic acid, neridronic acid, pamidronic acid, risedronic acid, tiludronic acid, zoledronic acid), SPC wording agreed by the PhVWP in February 2006 Section 4.4 Pamidronic acid and zoledronic acid: “Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported in patients with cancer receiving treatment regimens including bisphosphonates. Many of these patients were also receiving chemotherapy and corticosteroids. The majority of reported cases have been associated with dental procedures such as tooth extraction. Many had signs of local infection including osteomyelitis. A dental examination with appropriate preventive dentistry should be considered prior to treatment with bisphosphonates in patients with concomitant risk factors (e.g. cancer, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, corticosteroids, poor oral hygiene). While on treatment, these patients should avoid invasive dental procedures if possible. For patients who develop osteonecrosis of the jaw while on bisphosphonate therapy, dental surgery may exacerbate the condition. For patients requiring dental procedures, there are no data available to suggest whether discontinuation of bisphosphonate treatment reduces the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clinical judgement of the treating physician should guide the management plan of each patient based on individual benefit/risk assessment.” Remaining bisphosphonates: “Osteonecrosis of the jaw, generally associated with tooth extraction and/or local infection (including osteomyelits) has been reported in patients with cancer receiving treatment regimens including primarily intravenously administered bisphophonates. Many of these patients were also receiving chemotherapy and corticosteroids. Osteonecrosis of the jaw has also been reported in patients with osteoporosis receiving oral bisphophonates. A dental examination with appropriate preventive dentistry should be considered prior to treatment with bisphosphonates in patients with concomitant risk factors (e.g. -

834FM.1 ZOLEDRONIC ACID and IBANDRONIC ACID for ADJUVANT TREATMENT in EARLY BREAST CANCER PATIENTS (Amber Initiation Guideline for Ibandronic Acid)

834FM.1 ZOLEDRONIC ACID AND IBANDRONIC ACID FOR ADJUVANT TREATMENT IN EARLY BREAST CANCER PATIENTS (Amber Initiation Guideline for Ibandronic Acid) This guideline provides prescribing and monitoring advice for oral ibandronic acid therapy which may or may not follow zoledronic acid infusions in secondary care. It should be read in conjunction with the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) available on www.medicines.org.uk/emc and the BNF. BACKGROUND FOR USE Bisphosphonates are indicated for reduction in the risk of developing bone metastases and risk of death from breast cancer in post-menopausal patients who have had curative treatment for breast cancer, i.e. this is an adjuvant treatment. A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 26 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including 18,766 women with early breast cancer (the Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group [EBCTCG] meta- analysis 2015) has shown that at 10 years the absolute reductions in the risk of breast cancer mortality, bone recurrence and all-cause mortality in post-menopausal women were 3.3%, 2.2% and 2.3% respectively. Bone fractures were also reduced by 15%, which is highly relevant as many of the patients offered adjuvant bisphosphonates will also be recommended to have adjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment that can cause loss of bone density and bone fractures. In line with cancer services in Oxfordshire and other areas, we have chosen to use zoledronic acid for intravenous administration and ibandronic acid for oral administration due to availability and relatively low cost. These medications are licensed for use in patients with osteoporosis and metastatic breast cancer. -

Zoledronic Acid Teva, INN-Zoledronic Acid

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Zoledronic Acid Teva 4 mg/5 ml concentrate for solution for infusion 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION One vial with 5 ml concentrate contains 4 mg zoledronic acid (as monohydrate). One ml concentrate contains 0.8 mg zoledronic acid (as monohydrate). For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Concentrate for solution for infusion (sterile concentrate). Clear and colourless solution. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications - Prevention of skeletal related events (pathological fractures, spinal compression, radiation or surgery to bone, or tumour-induced hypercalcaemia) in adult patients with advanced malignancies involving bone. - Treatment of adult patients with tumour-induced hypercalcaemia (TIH). 4.2 Posology and method of administration Zoledronic Acid Teva must only be prescribed and administered to patients by healthcare professionals experienced in the administration of intravenous bisphosphonates. Posology Prevention of skeletal related events in patients with advanced malignancies involving bone Adults and older people The recommended dose in the prevention of skeletal related events in patients with advanced malignancies involving bone is 4 mg zoledronic acid every 3 to 4 weeks. Patients should also be administered an oral calcium supplement of 500 mg and 400 IU vitamin D daily. The decision to treat patients with bone metastases for the prevention of skeletal related events should consider that the onset of treatment effect is 2-3 months. Treatment of TIH Adults and older people The recommended dose in hypercalcaemia (albumin-corrected serum calcium ≥ 12.0 mg/dl or 3.0 mmol/l) is a single dose of 4 mg zoledronic acid. -

June 2011 Circular No

7 th June 2011 Circular No. P06/2011 Dear Healthcare Professional, Re: European Medicines Agency finalises review of bisphosphonates and atypical stress fractures Bisphosphonates have been authorised in the EU for hypercalcaemia and the prevention of bone problems in patients with cancer since the early 1990s. They have also been available since the mid 1990s for the treatment of osteoporosis and Paget’s disease of the bone. Bisphosphonates include alendronic acid, clodronic acid, etidronic acid, ibandronic acid, neridronic acid, pamidronic acid, risedronic acid, tiludronic acid and zoledronic acid. They are available in the EU as tablets and as solutions for infusion under various trade names and as generic medicines2. In 2008, the CHMP’s Pharmacovigilance Working Party (PhVWP) noted that alendronic acid was associated with an increased risk of atypical fracture of the femur (thigh bone) that developed with low or no trauma. As a result, a warning was added to the product information of alendronic acid-containing medicines across Europe. The PhVWP also concluded at the time that it was not possible to rule out the possibility that the effect could be a class effect (an effect common to all bisphosphonates), and decided to keep the issue under close review. In April 2010, the PhVWP noted that further data from both the published literature and post- marketing reports were now available that suggested that atypical stress fractures of the femur may be a class effect. The working party concluded that there was a need to conduct a further review to determine if any regulatory action was necessary. Page 1 of 3 Medicines Authority 203 Level 3, Rue D'Argens, Gzira, GZR 1368 – Malta. -

Zoledronic Acid Injection Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Zoledronic Acid Injection safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Zoledronic Acid Injection. • Adequately rehydrate patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy Zoledronic Acid Injection prior to administration of Zoledronic Acid Injection and monitor electrolytes during treatment. (5.2) for intravenous use • Renal toxicity may be greater in patients with renal impairment. Do Initial U.S. Approval: 2001 not use doses greater than 4 mg. Treatment in patients with severe renal impairment is not recommended. Monitor serum creatinine -------------------------RECENT MAJOR CHANGES--------------------- before each dose. (5.3) • Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported. Preventive dental exams Warnings and Precautions, Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (5.4) 06/2015 should be performed before starting Zoledronic Acid Injection. Avoid invasive dental procedures. (5.4) -------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE------------------------ • Severe incapacitating bone, joint, and/or muscle pain may occur. Zoledronic Acid Injection is a bisphosphonate indicated for the Discontinue Zoledronic Acid Injection if severe symptoms occur. treatment of: (5.5) • Hypercalcemia of malignancy. (1.1) • Zoledronic Acid Injection can cause fetal harm. Women of • Patients with multiple myeloma and patients with documented bone childbearing potential should be advised of the potential hazard to metastases from solid tumors, in conjunction with standard the fetus and to avoid becoming pregnant. (5.9, 8.1) antineoplastic therapy. Prostate cancer should have progressed after • Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures have been treatment with at least one hormonal therapy. (1.2) reported in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. These Important limitation of use: The safety and efficacy of Zoledronic Acid fractures may occur after minimal or no trauma. -

Bone Protection in Myeloma

Myeloma group BONE PROTECTION IN MYELOMA INDICATIONS • Long-term bisphosphonate therapy: This is the primary subject of this protocol. Prophylactic treatment should be given to all patients with myeloma requiring treatment, whether or not bone lesions are evident as per the BCSH Guidelines 20101 and should continue for at least 2 years.2 Discontinuing bisphosphonates after 2 years’ treatment in patients with well controlled disease, and restarting at relapse/progression is a reasonable approach. Therapy can be withheld 2 weeks prior to undergoing ASCT and re-initiated 2 months post-ASCT Denosumab is NOT routinely funded for bone protection in myeloma. For patients with renal impairment who are not eligible to receive bisphosphonates, Individual funding request must be approved prior to initiation of therapy. EVIDENCE • The 2012 Cochrane review suggested that adding bisphosphonates to the treatment of multiple myeloma reduces vertebral fracture, probably pain and possibly the incidence of hypercalcaemia.3 • For every 10 patients with myeloma treated with bisphosphonates one patient will avoid a vertebral fracture. • The Nordic myeloma study group compared the effect of two doses of (30 mg or 90 mg) pamidronate on health-related quality of life and skeletal morbidity in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in a randomised phase 3 trial. Primary outcome of physical function after 12 months and secondary outcome of time to first SRE were not significantly different in a 4 year follow up between the two drug doses.4 • Efficacy and safety of 120 mg Denosumab SC every 4 weeks or 4 mg zoledronic acid (dose- adjusted for reduced renal function) IV every 4 weeks were compared in three randomised, double blind, active controlled studies, in IV-bisphosphonate naïve patients with advanced malignancies involving bone: adults with breast cancer (study 1), other solid tumours or multiple myeloma (study 2), and castrate-resistant prostate cancer (study 3). -

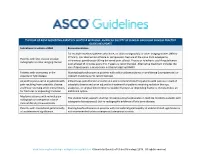

The Role of Bone Modifying

THE ROLE OF BONE MODIFYING AGENTS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA: AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE UPDATE Indications to initiate a BMA Recommendation For multiple myeloma patients who have, on plain radiograph(s) or other imaging studies (MRI or CT Scan), lytic destruction of bone or compression fracture of the spine from osteopenia, Patients with lytic disease on plain intravenous pamidronate 90 mg delivered over at least 2 hours or zoledronic acid 4 mg delivered radiographs or other imaging studies over at least 15 minutes every 3 to 4 weeks is recommended. Alternative treatment includes the use of denosumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL. Patients with osteopenia in the Starting bisphosphonates in patients with solitary plasmacytoma or smoldering (asymptomatic) or absence of lytic disease indolent myeloma is not recommended. Adjunct to pain control in patients with Intravenous pamidronate or zoledronic acid is recommended for patients with pain as a result of pain resulting from osteolytic disease osteolytic disease and as an adjunctive treatment for patients receiving radiation therapy, and those receiving other interventions analgesics, or surgical intervention to stabilize fractures or impending fractures. Denosumab is an for fractures or impending fractures additional option. Myeloma patients with normal plain The Update Panel supports starting intravenous bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma patients with radiograph or osteopenia in bone osteopenia (osteoporosis) but no radiographic evidence of lytic bone disease. mineral density measurements Patients with monoclonal gammopathy Starting bisphosphonates in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is of undetermined significance not recommended unless osteopenia (osteoporosis) exists. www.asco.org/hematologic-malignancies-guidelines ©American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018.