JAHR 4-2011.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

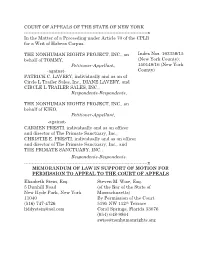

COURT of APPEALS of the STATE of NEW YORK ------X in the Matter of a Proceeding Under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on Index Nos. 162358/15 behalf of TOMMY, (New York County); Petitioner-Appellant, 150149/16 (New York -against- County) PATRICK C. LAVERY, individually and as an of Circle L Trailer Sales, Inc., DIANE LAVERY, and CIRCLE L TRAILER SALES, INC., Respondents-Respondents, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, Petitioner-Appellant, -against- CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents-Respondents. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL TO THE COURT OF APPEALS Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. 5 Dunhill Road (of the Bar of the State of New Hyde Park, New York Massachusetts) 11040 By Permission of the Court (516) 747-4726 5195 NW 112th Terrace [email protected] Coral Springs, Florida 33076 (954) 648-9864 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Authorities ................................................................................... iv Argument .................................................................................................... 1 I. Preliminary Statement -

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) - Utilitarianism

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) - Utilitarianism British economist Jeremy Bentham is most often associated with his theory of utilitarianism. Bentham's views ran counter to Adam Smith's vision of "natural rights." He believed in utilitarianism, or the idea that all social actions should be evaluated by the axiom "It is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong." Unlike Smith, Bentham believed that there were no natural rights to be interfered with. Trained in law, Bentham never practiced, choosing instead to focus on judicial and legal reform. His reform plans went beyond rewriting legislative acts to include detailed administrative plans to implement his proposals. In his plan for prisons, workhouses, and other institutions, Bentham devised compensation schemes, building designs, worker timetables, and even new accounting systems. A guiding principle of Bentham's schemes was that incentives should be designed "to make it each man's interest to observe on every occasion that conduct which it is his duty to observe." Interestingly, Bentham's thinking led him to the conclusion, one he shared with Smith, that professors should not be salaried. In his early years Bentham professed a free-market approach. He argued, for example, that interest rates should be free from government control. (See Defence of Usury.) But by the end of his life, he had shifted to a more interventionist stance. He predated Keynes in his advocacy of expansionist monetary policies to achieve full employment and advocated a range of interventions, including the minimum wage and guaranteed employment. His publications were few, but Bentham influenced many during his lifetime and lived to see some of his political reforms enacted shortly before his death in London at the age of eighty-four. -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer

03/05/2017 Arthur Schopenhauer (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer First published Mon May 12, 2003; substantive revision Sat Nov 19, 2011 Among 19th century philosophers, Arthur Schopenhauer was among the first to contend that at its core, the universe is not a rational place. Inspired by Plato and Kant, both of whom regarded the world as being more amenable to reason, Schopenhauer developed their philosophies into an instinctrecognizing and ultimately ascetic outlook, emphasizing that in the face of a world filled with endless strife, we ought to minimize our natural desires for the sake of achieving a more tranquil frame of mind and a disposition towards universal beneficence. Often considered to be a thoroughgoing pessimist, Schopenhauer in fact advocated ways — via artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness — to overcome a frustrationfilled and fundamentally painful human condition. Since his death in 1860, his philosophy has had a special attraction for those who wonder about life's meaning, along with those engaged in music, literature, and the visual arts. 1. Life: 1788–1860 2. The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason 3. Schopenhauer's Critique of Kant 4. The World as Will 5. Transcending the Human Conditions of Conflict 5.1 Aesthetic Perception as a Mode of Transcendence 5.2 Moral Awareness as a Mode of Transcendence 5.3 Asceticism and the Denial of the WilltoLive 6. Schopenhauer's Later Works 7. Critical Reflections 8. Schopenhauer's Influence Bibliography Academic Tools Other Internet Resources Related Entries 1. Life: 1788–1860 Exactly a month younger than the English Romantic poet, Lord Byron (1788–1824), who was born on January 22, 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer came into the world on February 22, 1788 in Danzig [Gdansk, Poland] — a city that had a long history in international trade as a member of the Hanseatic League. -

A Feminist Caring Ethic for the Treatment of Animals

81 ATTENTION TO SUFFERING: A FEMINIST CARING ETHIC FOR THE TREATMENT OF ANIMALS Josephine Donovan Many feminists, including myself, have criticized contemporary animal welfare theory for its reliance upon natural rights doctrine, on the one hand, and utilitarianism on the other. The main exponent of the former approach has been Tom Regan, and of the latter, Peter Singer. However incompatible the two theories may be, they nevertheless unite in their rationalist rejection of emotion or sympathy as a legitimate base for ethical theory about animal treatment. Many feminists have urged just the opposite, claiming that sympathy, compassion, and caring are the ground upon which theory about human treatment of animals should be constructed. Here I would like to further deepen this assertion. To do so I will argue that the terms of what constitutes the ethical must be shifted. Like many other feminists, I contend that the dominant strain in contemporary ethics reflects a male bias toward rationality, defined as the construction of abstract universals that elide not just the personal, the contextual, and the emotional, but also the political compo- nents of an ethical issue. Like other feminists, particularly those in the "caring" tradition, I believe that an alternative epistemology and ontol- ogy may be derived from women's historical social, economic, and political practice. I will develop this point further below. In addition to recent feminist theorizing, however, there is a long and important strain in Western (male)philosophy that does not express the rationalist bias of contemporary ethical theory, that in fact seeks to root ethics in emotion-in the feelings of sympathy and compassion. -

An Ecocritical Examination of Whale Texts

Econstruction: The Nature/Culture Opposition in Texts about Whales and Whaling. Gregory R. Pritchard B.A. (Deakin) B.A. Honours (Deakin) THESIS SUBMITTED IN TOTAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. FACULTY OF ARTS DEAKIN UNIVERSITY March 2004 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their assistance in the research and production of this thesis: Associate Professor Brian Edwards, Dr Wenche Ommundsen, Dr Elizabeth Parsons, Glenda Bancell, Richard Smith, Martin Bride, Jane Wilkinson, Professor Mark Colyvan, Dr Rob Leach, Ian Anger and the staff of the Deakin University Library. I would also like to acknowledge with gratitude the assistance of the Australian Postgraduate Award. 2 For Bessie Showell and Ron Pritchard, for a love of words and nature. 3 The world today is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot. In my world of beach and dune these elemental presences lived and had their being, and under their arch there moved an incomparable pageant of nature and the year. The flux and reflux of ocean, the incomings of waves, the gatherings of birds, the pilgrimages of the peoples of the sea, winter and storm, the splendour of autumn and the holiness of spring – all these were part of the great beach. The longer I stayed, the more eager was I to know this coast and to share its mysteries and elemental life … Edward Beston, The Outermost House Premises of the machine age. -

The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series

The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series editors: Andrew Linzey and Priscilla Cohn Associate editor: Clair Linzey In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed, from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. This series explores the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifically, the series will ● provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals, ● publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars, and ● produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in char- acter or have multidisciplinary relevance. Titles include Elisa Aaltola ANIMAL SUFFERING: PHILOSOPHY AND CULTURE Aysha Akhtar ANIMALS AND PUBLIC HEALTH Why Treating Animals Better Is Critical to Human Welfare Alasdair Cochrane AN INTRODUCTION TO ANIMALS AND POLITICAL THEORY Eleonora Gullone ANIMAL CRUELTY, ANTISOCIAL BEHAVIOUR, AND HUMAN AGGRESSION More than a Link Alastair Harden ANIMALS IN THE CLASSICAL WORLD Ethical Perspectives from Greek and Roman Texts Lisa Johnson POWER, KNOWLEDGE, ANIMALS Andrew Knight THE COSTS AND BENEFITS OF ANIMAL EXPERIMENTS Randy Malamud AN INTRODUCTION TO ANIMALS IN VISUAL CULTURE Ryan Patrick McLaughlin CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY AND -

Animism, Empathy and Human Development

Animism,1 Empathy and Human Development Michael W. Fox The Humane Society of the United States That people do feel pain when the earth is damaged is afflI1Iled by a Wintu Indian woman ofCalifornia who said, "We don't chop down trees. We only use dead wood. But the white people plow up the ground, pull down the trees, kill everything. The tree says, 'Don't. I am sore. Don't hurt me.' ... They blast rocks and scatter them on the ground. The rock says, 'Don't. You are hurting me."'} Such empathy lcads to a feeling of kinship with all life. Lakota ChiefLuther Standing Bear wrote: "Kinship with all creatures of the earth, sky and water, was a real Surely it is time for us all to make every effort to evolve and active principle. For the animal and bird world there as a species and become more fully human. To be fully existed a brotherly feeling that kept the Lakota safe human is to be humane. To be sub-human is to be among them and so elose did some of the Lakotas eome inhumane. In order to evolve in this way and become to their feathered and furred friends that in true more fully human we must defme and refine our ethical brotherhood they spoke a common tongue.,,3 Chief and spiritual responsibilities and sensibilities. And we Luther also asserted that lack of respect for growing, must redefine what it means to be human. 'Ine origin of living things soon led to lack ofrespect for humans also. -

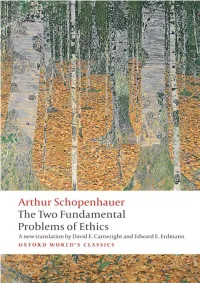

Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford Ox2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York Translation, Note on the Text and Translation, Select Bibliography, Chronology, Explanatory Notes © David E. Cartwright and Edward E. Erdmann 2010 Introduction © Christopher Janaway 2010 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above -

On Reading and Books

Space for Notes Arthur Schopenhauer ↓ Parega and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays* (1851) Chapter XXIV On Reading and Books § 290 Ignorance degrades a man only when it is found in company with wealth. A poor man is subdued by his poverty and distress; with him his work takes the place of knowledge and occupies his thoughts. On the other hand, the wealthy who are ignorant live merely for their pleasures and are like animals, as can be seen every day. Moreover, there is the reproach that wealth and leisure have not been used for that which bestows on them the greatest possible value. § 291 When we read, someone else thinks for us; we repeat merely his mental process. It is like the pupil who, when learning to write, goes over with his pen the strokes made in pencil by the teacher. Accordingly, when we read, the work of thinking is for the most part taken away from us. Hence the noticeable relief when from preoccupation with our thoughts we pass to reading. But while we are reading our mind is really only the playground of other people’s ideas; and when these finally depart, what remains? The result is that, whoever reads very much and almost the entire day but at intervals amuses himself with thoughtless pastime, gradually loses the ability to think for himself; just as a man who always rides ultimately forgets how to walk. But such is the case with very many scholars; they have read themselves stupid. For constant reading, which is at once resumed at every free moment, is even more paralysing to the mind than is manual work; for with the latter we can give free play to our own thoughts. -

A Genre That Matters: Schopenhauer on the Ethical Significance of Tragedy

1 A Genre that Matters: Schopenhauer on the Ethical Significance of Tragedy A work in progress Sandy Shapshay, Dept. of Philosophy, Indiana University When even the best of us hear Homer or some other tragedian imitating one of the heroes sorrowing and making a long lamenting speech or singing and beating his breast, you know that we enjoy it, give ourselves up to following it, sympathize with the hero, take his sufferings seriously, and praise as a good poet the one who affects us most in this way. Plato Republic 605cd. One of the most vital areas in contemporary aesthetics concerns the experience of so- called “negative” emotions in an engagement with fiction. One persistent puzzle since the time of Aristotle is the problem of tragedy: How is it that we take pleasure in the inherently unpleasant emotions of fear and pity experienced in a serious engagement with tragic drama? The problem in its Humean formulation is generated by three propositions that seem mutually inconsistent: 1. Many people do enjoy tragedies 2. Typically one experiences unpleasant emotions such as anxiety, sorrow, pity, and fear as part of one’s emotional response to tragedies. 3. Generally those same people who enjoy tragedies do not seek out or enjoy the experience painful emotions in real life (outside of the theater). The charge is that those who seek out and enjoy tragedies are acting irrationally. If people don’t welcome and enjoy scenes of terrible suffering in real life, then why would 2 they seek out those scenes and enjoy them in tragic drama? The paradoxical nature of tragic pleasure is heightened by the fact that the tremendous value attributed to tragedy as an art form seems to derive precisely from the suffering it evokes as well as from the serious and terrible events depicted.1 As is well known, Aristotle, Burke, Hume, Nietzsche (to name just a few of the historical heavy-hitters) and scores of contemporary aestheticians have recognized that the apparent pleasure people derive in the experience of tragedy calls for an explanation. -

Death Drive in Psychoanalysis Versus Existential Psychotherapy

Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal ISSN 2474-7688 Mini Review Psychol Behav Sci Int J Volume 8 Issue 1 - December 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Pari Tirsahar DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.08.555726 Death Drive In Psychoanalysis versus Existential Psychotherapy Pari Tirsahar* University of Tutor, UK Submission: November 15, 2017; Published: December 05, 2017 *Corresponding author: Pari Tirsahar, University of Tutor, London, UK, Email: Introduction In by [6] says that the In Greek myth, the demon of death was the son of Nix (god Civilisation and Its Discontents S Freud pleasure principle determines the purpose of life thus being of the night) and Erebus (god of darkness) and a twin to Hypnos analogous to the reality principle. But then Freud realized that time 1920 in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, according to which (sleep). The term ‘death drive’ was coined by Freud for the first could not explain with the pleasure principle, and that led him to ‘Thanatos‘ is posited opposite of Eros, the creative and productive there were three conflicting facts in the human mind that he another principle which he found beyond the pleasure principle, drives, sexuality and survival. In classic psychoanalytic theory and this in turn led him to the concept that later became known the death drive (Thanatos) is seen as a drive towards self- as the death drive. destruction and death. The death drive forces mankind into risky and self-destructive behaviors that could lead to death S Freud [1]. The death drive can be related to the work of the German was the paradox of PTSD in working with traumatized soldiers The first conflicting problem Freud was confronted with philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer who in his book The World who had participated in World War I. -

Plato's Conception of Time at the Foundation of Schopenhauer's

chapter 9 Plato’s Conception of Time at the Foundation of Schopenhauer’s Philosophy Robert Wicks When commonly thinking about Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophy, Plato’s influence does not immediately come to mind. Schopenhauer’s reputation as a “pessimist” is probably the first thought, and if one’s acquaintance is more than passing, his belief that a meaningless, blind “Will” is at the bottom of all things quickly follows. Perhaps next, in no particular order, are his vanguard incorpo- ration of Asian thought into Western philosophy, his bitter condemnations of G.W.F. Hegel and salaried university professors, the uncomfortable anecdote of his having angrily thrown a noisy cleaning woman down a staircase in a fit of frustration, and for those who are more well-versed, his deep and abiding influence on Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche. Concerning Plato, most scholarly discussions of Schopenhauer tend to con- centrate on the status and role of Platonic Ideas in his philosophy, usually in reference to how they inform Schopenhauer’s aesthetic theory.1 This is a fruit- ful approach, as circumscribed as it is, and we will consider Schopenhauer’s understanding of Platonic Ideas near the end of this essay. More important, however, is to situate such an inquiry within the context of the more funda- mental recognition that Schopenhauer’s initial reading of Plato, a philosopher he often called “the divine”, set the groundwork for Schopenhauer’s philosoph- ical ascension to a so-called better consciousness through art, morality and asceticism. In the absence of this wider context, it is easy to overlook how Plato’s ini- tial influence kindled the driving insight at the foundation of Schopenhauer’s philosophy—an insight more deep-seated than Schopenhauer’s famous metaphysical apprehension that the world is Will.