Greek Folk-Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

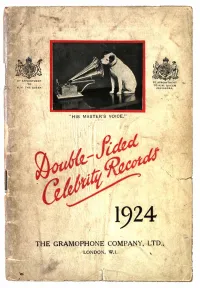

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Greek Body in Crisis: Contemporary Dance as a Site of Negotiating and Restructuring National Identity in the Era of Precarity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0vg4w163 Author Zervou, Natalie Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Greek Body in Crisis: Contemporary Dance as a Site of Negotiating and Restructuring National Identity in the Era of Precarity A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Natalie Zervou June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Marta Elena Savigliano, Chairperson Dr. Linda J. Tomko Dr. Anthea Kraut Copyright Natalie Zervou 2015 The Dissertation of Natalie Zervou is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments This dissertation is the result of four years of intensive research, even though I have been engaging with this topic and the questions discussed here long before that. Having been born in Greece, and having lived there till my early twenties, it is the place that holds all my childhood memories, my first encounters with dance, my friends, and my family. From a very early age I remember how I always used to say that I wanted to study dance and then move to the US to pursue my dream. Back then I was not sure what that dream was, other than leaving Greece, where I often felt like I did not belong. Being here now, in the US, I think I found it and I must admit that when I first begun my pursuit in graduate studies in dance, I was very hesitant to engage in research concerning Greece. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Modeling Radar Rainfall Estimation Uncertainties: Random Error Model A

Modeling Radar Rainfall Estimation Uncertainties: Random Error Model A. AghaKouchak1; E. Habib2; and A. Bárdossy3 Abstract: Precipitation is a major input in hydrological models. Radar rainfall data compared with rain gauge measurements provide higher spatial and temporal resolutions. However, radar data obtained form reflectivity patterns are subject to various errors such as errors in reflectivity-rainfall ͑Z-R͒ relationships, variation in vertical profile of reflectivity, and spatial and temporal sampling among others. Characterization of such uncertainties in radar data and their effects on hydrologic simulations is a challenging issue. The superposition of random error of different sources is one of the main factors in uncertainty of radar estimates. One way to express these uncertainties is to stochastically generate random error fields and impose them on radar measurements in order to obtain an ensemble of radar rainfall estimates. In the present study, radar uncertainty is included in the Z-R relationship whereby radar estimates are perturbed with two error components: purely random error and an error component that is proportional to the magnitude of rainfall rates. Parameters of the model are estimated using the maximum likelihood method in order to account for heteroscedasticity in radar rainfall error estimates. An example implementation of this approached is presented to demonstrate the model performance. The results confirm that the model performs reasonably well in generating an ensemble of radar rainfall fields with similar stochastic characteristics and correlation structure to that of unperturbed radar estimates. DOI: 10.1061/͑ASCE͒HE.1943-5584.0000185 CE Database subject headings: Rainfall; Simulation; Radars; Errors; Models; Uncertainty principles. Author keywords: Rainfall simulation; Radar random error; Maximum likelihood; Rainfall ensemble; Uncertainty analysis. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Mediterranean Divine Vintage Turkey & Greece

BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Neapolis Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Abdera Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA JOINAllante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Elimia PydnaMEDITERRANEAN Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Dasaki Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos Torone Hephaistia Dorylaeum BOZCAADA Sigeion Kenchreai Omphatium Gonnus Skione Limnos MYSIA Uludag ESKİŞEHİR Eritium DIVINE VINTAGE Derecik Basilica Sidari Oxynia Myrina Kaz Mt. Passaron Soufli Troas Kebrene Skepsis UNESCO Meliboea Cassiope Gure bath BALIKESİR Dikilitaş Kanlıtaş Höyük Aiginion Neandra Karacahisar Castle Meteora Antandros Adramyttium Corfu UNESCO Larissa Lamponeia Dodoni Theopetra Gülpinar Pioniai Kulluoba Hamaxitos Seyitömer Höyük Keçi çayırı Syvota KÜTAHYA Grava Polimedion Assos Gerdekkaya Assos Mt.Pelion A E GTURKEY E A N S E A &Pyrrha GREECEMadra Mt. (Cotiaeum) Kumbet Lefkimi Theudoria Pherae Mithymna Midas City Ellina EPIRUS Passandra Perperene Lolkos/Gorytsa Antissa Bahses Mt. -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION -

Storm Rips Manchester, Kills Power

to - MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. Sept, 6, 1985 MANCHESTER FOCUS SPORTS WEATHER TOWN OF MANCHUT1R CAR8/TRUCK8 LIOAL NOTICI TAG SALES |F0R8ALE Tht Planning ond Zoning Commlulon will hold o public Meanest cut of all Manchester soccer Gloudy, hot today; htorlnd on WtdnMdov, Stpttmbgr II, 1015 at 7:00 P.M. In th t BUSINESS & SERVICE DIRECTORY Town history museum Htorlng Room, Lincoln Ctntar, 494 Main Strott, Manchn- Multi Family — This wee 1980 Ford Fiesta — Hatch ttr, Oonnoctlcut to hear and conildgr the following peti kend beginning Friday. back, standard, radial, has new personality little change Sunday tion*: won’t open this fall can happen to you R ER V il^ FAHITIN6/ I BUIL0IN8/ Too many Items to list, good condtion, A M /F M T H l IiaH TH U T ILITIH DISTRICT ■ ZONING RIGULA- SERVICES Radio, 4 speed. $2,195. l o i j j PAFERHiO CONTRACTINQ 133-140 Strawberry Lane, ... p a g e 2 TION AMENDMENT (E-m - To amend Article II. Section OFFERS! QFEREO Best offer. 646-6876. ... p a g e 3 ... page 111 ... page 15 10.01 to allow municipal office*, police itaflon* and fire Manchester.____________ hou*e> a* permitted uie* provided the (Ite abut* a molor or minor orterlol o* defined by fhe Town'* Plan of Develop Odd lobs. Trucking. Office Machine Repairs Falntmg^ — ComoWe Garage Sale — Friday & ment. and Cleaning-Free pick log - Extertor and lnt» “ nd^emcJ Home reoairs. You name bp dnddellverv.ao Years rior, ceilings rw irrt. ^ e rw m ^ rem^ Saturday, 10am-2pm. ALBERT LINDSAY - SPECIAL EXCEPTION • TAYLOR It, wo do It, Pree esti w . -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

A Preliminary List of Shallow Water Decapod Crustacea in the Kerama Group, the Ryukyu Archipelago

Bull Biogeogr. Soc. Japan 日本生物地理学会会報 51(2): 7-21. Dec. 20,1996 第 5 1巻第 2号1 996 年1 2 月 20 日 A preliminary list of shallow water decapod Crustacea in the Kerama Group, the Ryukyu Archipelago Keiichi Nomura, Seiji Nagai, Akira Asakura and Tomoyuki Komai Abstract. During a faunal survey of the Kerama いroup in 1978 and 1992-1994,S. Nagai and K. Nomura made intensive collections of decapod crustaceans. The material includes 299 species representing 37 families,excluding the Chirostylidae and Galatheidae. Of these, 47 species remain to be unidentified, because they include possibly undescribed or taxonomically proolematical species. First Japanese records are reported for the following 21 species, most of wmch are considered to be widely distributed in tropical and subtropical waters of the West Pacific or Indo-West Pacific: Odontozona ensifera, Discias exul, Leptochela irrobusta, Hamodactylus boshmai’ Periclimenaeus djiboutensis, P. hecate, Periclimenes amboinensis, P. cristimanus, P. novaecaledoniae, P. longirostris, Alpheus ehlersii, A. pareuchirus, A, tenuipes, Parabetaeus culliereti, Axiopsis serratifrons, Pylopaguropsis fimbriata, Petrolisthes extremus, Hyastenus uncifer, Tiarinia dana, Portunus mariei and Hypocolpus rugosus. Key words: Crustacea, Decapoda, Fauna, Kerama, Ryukyu Introduction seven species of porcellanid crab in intertidal zone of The Kerama Group, which belongs to the Okinawa Zamami-jima. Recently, Okuno (1994) recorded Islands, the Ryukyu Archipelago, is located 30 km three species of rhynchocinetid shrimps, including a west of Okinawa-jima,and consists of about 20 new species, Rhynchocinetes concolor, from Aka- islands of various sizes. Despite the considerable jima. development of coral reef and related environment, its During a faunal survey of the Kerama Group in marine fauna has been little studied in the past.