Signature Redacted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loan Agreement

CONFORMED COPY LOAN NUMBER 4794-CHA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Loan Agreement (Chongqing Small Cities Infrastructure Improvement Project) between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Public Disclosure Authorized and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Dated September 10, 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized 2 LOAN NUMBER 4794-CHA LOAN AGREEMENT AGREEMENT, dated September 10, 2005, between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (the Borrower) and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (the Bank). WHEREAS (A) the Borrower, having satisfied itself as to the feasibility and priority of the project described in Schedule 2 to this Agreement (the Project), has requested the Bank to assist in the financing of the Project; (B) the Project will be carried out by Chongqing (as defined in Section 1.02) with the Borrower’s assistance and, as part of such assistance, the Borrower will make the proceeds of the loan provided for in Article II of this Agreement (the Loan) available to Chongqing, as set forth in this Agreement; and WHEREAS the Bank has agreed, on the basis, inter alia, of the foregoing, to extend the Loan to the Borrower upon the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement and in the Project Agreement of even date herewith between the Bank and Chongqing (the Project Agreement); NOW THEREFORE the parties hereto hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I General Conditions; Definitions Section 1.01. The “General Conditions Applicable to Loan and Guarantee Agreements for Single Currency Loans” of the Bank, dated May 30, 1995 (as amended through May 1, 2004) with the following modification (the General Conditions), constitute an integral part of this Agreement, namely, that Section 6.03(c) of the General Conditions is amended by replacing the words “corrupt or fraudulent” with the words “corrupt, fraudulent, collusive or coercive”. -

Spatiotemporal Evolution Analysis of Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution Risks in Chongqing, China, Based on the Ito3de Model and GIS

Spatiotemporal evolution analysis of agricultural non-point source pollution risks in Chongqing, China, based on the ITO3dE model and GIS Kang-wen ZHU Southwest University Zhi-min YANG Southwest University Lei HUANG Southwest University Yu-cheng CHEN ( [email protected] ) Southwest University Sheng ZHANG Chongqing Academy of Ecology and Environmental Sciences Hai-ling XIONG Southwest University Sheng WU Southwest University Bo LEI Chongqing Academy of Ecology and Environmental Sciences Research Article Keywords: Agricultural non-point source pollution (AGNPS), ITO3dE model, Transition matrix, Kernel density, GIS Posted Date: December 9th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-115722/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at Scientic Reports on February 25th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84075-2. 1 Spatiotemporal evolution analysis of agricultural non-point source pollution risks in 2 Chongqing, China, based on the ITO3dE model and GIS 3 Kang-wen ZHUa, Zhi-min YANGa, Lei HUANGa, Yu-cheng CHENa*, Sheng ZHANGb*, Hai-ling 4 XIONGc, Sheng WUc, Bo LEIb 5 aCollege of Resources and Environment, Southwest University, 400716, China 6 bChongqing Academy of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Chongqing, 401147, China 7 cCollege of computer & information science, Southwest University, 400716, China 8 Abstract 9 To determine the risk state distribution, risk level, and risk evolution situation of agricultural non-point source 10 pollution (AGNPS), we built an ‘Input-Translate-Output’ three-dimensional evaluation (ITO3dE) model that 11 involved 12 factors under the support of GIS and analyzed the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of AGNPS 12 risks from 2005 to 2015 in Chongqing by using GIS space matrix, kernel density analysis, and Getis-Ord Gi* analysis. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Chongqing Urban–Rural Infrastructure Development Demonstration II Project — Resettlement External Monitoring Report (No

Resettlement External Monitoring Report #7 June–December 2018 January 2019 People’s Republic of China: Chongqing Urban–Rural Infrastructure Development Demonstration II Project — Resettlement External Monitoring Report (No. 7) Prepared by the Halcrow (Chongqing) Engineering Consulting Co. Ltd. for the People’s Republic of China and the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement external monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB-Financed Chongqing Urban–Rural Infrastructure Development Demonstration Project II Resettlement External Monitoring Report (No. 7) (Jun 2018---Dec 2018) Halcrow (Chongqing) Engineering Consulting Co. Ltd. Jan 2019 I Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. II 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Brief Introduction of the Project .................................................................................................................. -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

Brochure of the 11Th Pan-Beibu Gulf Economic Cooperation Forum

Contents I. Agenda...….…………………….......……………....….…………………02 II. List of Delegates......……………..………………....….……………………11 III. Registration ………………….......……………....….……………………33 IV. Catering ……………………………….......…...……...……………………34 V. Service Information…………….....…………………….......…...…..…35 Airport ..................................................................………........................…35 Hotel................................................................…………..............................35 Local Transport.........................…………………………............................35 Registration.................................................……………..……………........35 Pandemic Prevention and Control.................................................................36 Medical Services..........................................................................................36 Food Safety...................................................................................................36 Hotel Notes...................................................................................................36 VI. Security...........……………...….....................................................…...……37 VII. Notes...........……………...…..........................................................…...……38 VIII. Background Information...........……………...…..........................…...……39 Pan-Beibu Gulf Economic Cooperation Forum...........……………...….....39 China-ASEAN Port Cities Cooperation Network Work Conference...........42 Pan-Beibu Gulf Think Tank Summit.............................................…...……43 -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Table S1 Sample information for the 36 Bactrocera minax populations and 8 Bactrocera tsuneonis populations used in this study Species Collection site Code Latitude Longitude Accession number B. minax Shimen County, Changde SM 29.6536°N 111.0646°E MK121987 - City, Hunan Province MK122016 Hongjiang County, HJ 27.2104°N 109.7884°E MK122052 - Huaihua City, Hunan MK122111 Province 27.2208°N 109.7694°E MK122112 - MK122144 Jingzhou Miao and Dong JZ 26.6774°N 109.7341°E MK122145 - Autonomous County, MK122174 Huaihua City, Hunan Province Mayang Miao MY 27.8036°N 109.8247°E MK122175 - Autonomous County, MK122204 Huaihua City, Hunan Province Luodian county, Qiannan LD 25.3426°N 106.6638°E MK124218 - Buyi and Miao MK124245 Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province Dongkou County, DK 27.0806°N 110.7209°E MK122205 - Shaoyang City, Hunan MK122234 Province Shaodong County, SD 27.2478°N 111.8964°E MK122235 - Shaoyang City, Hunan MK122264 Province 27.2056°N 111.8245°E MK122265 - MK122284 Xinning County, XN 26.4652°N 110.7256°E MK122022 - Shaoyang City,Hunan MK122051 Province 26.5387°N 110.7586°E MK122285 - MK122298 Baojing County, Xiangxi BJ 28.6154°N 109.4081°E MK122299 - Tujia and Miao MK122328 Autonomous Prefecture, Hunan Province 28.2802°N 109.4581°E MK122329 - MK122358 Guzhang County, GZ 28.6171°N 109.9508°E MK122359 - Xiangxi Tujia and Miao MK122388 Autonomous Prefecture, Hunan Province Luxi County, Xiangxi LX 28.2341°N 110.0571°E MK122389 - Tujia and Miao MK122407 Autonomous Prefecture, Hunan Province Yongshun County, YS 29.0023°N -

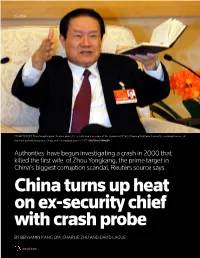

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Operational Guidance Note

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE NOTE CHINA OGN v.12 Issued October 2013 – updated 6 December 2014 OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE NOTE CHINA CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 – 1.4 2. Country assessment 2.1 Actors of protection 2.2 Internal relocation 2.3 Country guidance caselaw 2.4 3. Main categories of claims 3.1 – 3.8 Falun Gong/Falun Dafa 3.9 Involvement with pro-Tibetan/pro/independence political organisations 3.10 Involvement with illegal religious organisations 3.11 Involvement with illegal political organisations or perceived political 3.12 opposition Forced abortion/sterilisation under ‘one child policy’ 3.13 Double Jeopardy 3.14 Civil protests and petitioners 3.15 Prison Conditions 3.16 4. Minors claiming in their own right 4.1 – 4.3 5. Medical Treatment 5.1 – 5.5 6. Returns 6.1 – 6.5 Decision makers assessing claims based on Christianity should refer to the Country Information and Guidance on: ► China: Christians, 13 June 2014 1. Introduction 1.1 This document provides Home Office caseworkers with guidance on the nature and handling of the most common types of claims received from nationals/residents of China, including whether claims are or are not likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or Discretionary Leave. Caseworkers must refer to the relevant Asylum Instructions for further details of the policy on these areas. 1.2 Caseworkers must not base decisions on the country of origin information in this guidance; it is included to provide context only and does not purport to be comprehensive. The conclusions in this guidance are based on the totality of the available evidence, not just the brief extracts contained herein, and caseworkers must likewise take into account all available evidence. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement October 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 44 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 49 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 56 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 60 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

RP863 V2 Chongqing Urban and Rural

RP863 v2 Public Disclosure Authorized Chongqing Urban and Rural Integrated Pilot Project Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Chongqing World Bank Project Management Office Chongqing Technology and Business University Dec. 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 18 1 Project Introduction In August 2008, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) formally approved the 84 million USD Chongqing Integrated Urban and Rural Development project (Phase 1) and enlisted it into the Three-year Rolling Plan (2009~2011) of the World Bank Project to facilitate the process and the key tasks of the Chongqing integrated urban and rural development and reform. On the basis of this, the Project management Office (PMO) of the World Bank-funded Chongqing Integrated Urban and Rural Development and Reform Pilot Project under the Chongqing Municipal Development and Reform Commission have reviewed and screened 16 pilot projects based on the principles of “ urgency”,” “ representativeness”, “ effectiveness” and “ public welfare”. The estimated total investment of these projects is 1.31758 billion CNY and 84 million USD will be applied from the World Bank loan. These projects include: • Urban infrastructure construction, including 4 road subprojects and 3 water supply subprojects; • New countryside construction pilot village, including 4 subprojects regarding village road, comprehensive service, safe drinking water, ecological environment, new energy development, rural water resource infrastructure etc; • The capacity building for improving the employing capacity of the migrant workers, including 3 subprojects concerning the employment training centers for the rural surplus labor force; • The grassroots sanitation service system, including 2 subprojects with regard to constructing urban community service center, urban community service station, rural town (township) sanitation station and village sanitation offices etc.