Estonia in the European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Background Report Estonia

OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools Country Background Report Estonia This report was prepared by the Ministry of Education and Research of the Republic of Estonia, as an input to the OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools (School Resources Review). The participation of the Republic of Estonia in the project was organised with the support of the European Commission (EC) in the context of the partnership established between the OECD and the EC. The partnership partly covered participation costs of countries which are part of the European Union’s Erasmus+ programme. The document was prepared in response to guidelines the OECD provided to all countries. The opinions expressed are not those of the OECD or its Member countries. Further information about the OECD Review is available at www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm Ministry of Education and Research, 2015 Table of Content Table of Content ....................................................................................................................................................2 List of acronyms ....................................................................................................................................................7 Executive summary ...............................................................................................................................................9 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................10 -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Enlargement, Hospitality and Transformative Powers the Cases of Moldova and Ukraine by Jeppe Juul Petersen (Copenhagen)

ENLARGEMENT, HOSPITALITY AND TRANSFORMATIVE POWERS The Cases of Moldova and Ukraine by Jeppe Juul Petersen (Copenhagen) First publication. The European Union has undergone tremendous changes in recent years with the most comprehensive enlargement in its history. On May 1, 2004 ten new countries acceded to the EU (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Malta 1 Cf. Dinan, Desmond: Europe and Cyprus) and more countries are eager to join or have even been accepted as candidate recast. a history of European union. countries for entry into the European Union. Recently, Romania and Bulgaria followed the Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan ten newcomers as they finished their accession process and became members of the EU in 2004, p. 267. January 2007. Currently, the EU consists of 27 countries, with a population of roughly 500 2 Leonard, Mark/Grant, Charles: million and the largest economy in the world. Georgia and the EU. Can Europe’s Regardless of the incongruence between the old member states of the EU, the enlarge- neighbourhood policy deliver? Centre ment seemed inevitable since the reunited Europe could not restrict itself to the western for European Reform Policy Brief part of Europe.1 Thus, the enlargement processes of the EU can indeed be viewed as an 2005, p. 1. example of a reunification and integration process of Europe after the end of the Cold War. 3 Wolczuk, Kataryna: Ukraine after The countries that were previously linked to the USSR (e.g. Poland, Czech Republic and the Orange Revolution. Centre for Hungary) or the Warsaw Pact, now enjoy independence and are on the path of democracy European Reform Policy Paper 2005, and market economy, which constitute the membership criteria adopted by the European p. -

List of Prime Ministers of Estonia

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Konstantin Päts 24-02 1918 26-11 1918 Rural League 2 Konstantin Päts 26-11 1918 08-05 1919 Rural League 3 Otto August Strandman 08-05 1919 18-11 1919 Estonian Labour Party 4 Jaan Tõnisson 18-11 1919 28-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 5 Ado Birk 28-07 1920 30-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 6 Jaan Tõnisson 30-07 1920 26-10 1920 Estonian People's Party 7 Ants Piip 26-10 1920 25-01 1921 Estonian Labour Party 8 Konstantin Päts 25-01 1921 21-11 1922 Farmers' Assemblies 9 Juhan Kukk 21-11 1922 02-08 1923 Estonian Labour Party 10 Konstantin Päts 02-08 1923 26-03 1924 Farmers' Assemblies 11 Friedrich Karl Akel 26-03 1924 16-12 1924 Christian People's Party 12 Jüri Jaakson 16-12 1924 15-12 1925 Estonian People's Party 13 Jaan Teemant 15-12 1925 23-07 1926 Farmers' Assemblies 14 Jaan Teemant 23-07 1926 04-03 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 15 Jaan Teemant 04-03 1927 09-12 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 16 Jaan Tõnisson 09-12 1927 04-121928 Estonian People's Party 17 August Rei 04-121928 09-07 1929 Estonian Socialist Workers' Party 18 Otto August Strandman 09-07 1929 12-02 1931 Estonian Labour Party 19 Konstantin Päts 12-02 1931 19-02 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 20 Jaan Teemant 19-02 1932 19-07 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 21 Karl August Einbund 19-07 1932 01-11 1932 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 22 Konstantin Päts 01-11 1932 18-05 1933 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 23 Jaan Tõnisson 18-05 1933 21-10 1933 National Centre Party 24 Konstantin Päts 21-10 1933 24-01 1934 Non-party 25 Konstantin Päts 24-01 1934 -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

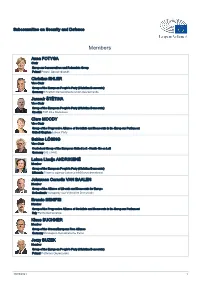

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

![Turkey Country Report – Update November 2017 [3Rd Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5597/turkey-country-report-update-november-2017-3rd-edition-645597.webp)

Turkey Country Report – Update November 2017 [3Rd Edition]

21 November 2017 (COI up to 11th September 2017) Turkey Country Report – Update November 2017 [3rd edition] Explanatory Note Sources and databases consulted List of Acronyms CONTENTS 1. Main Developments since the attempted Coup d’état (July 2016) a. Overview of major legislative and political developments: i. Recent legislative developments incl. new amendments or decrees 1. State of Emergency 2. Emergency decrees a. Decree of 22 July 2016 (KHK/667) b. Decree of 25 July 2016 (KHK/668) c. Decree of 31 July 2016 (KHK/669) d. Decrees of 17 August 2016 (KHK/670 and 671) e. Decrees of 1 September 2016 (KHK/672, 673 and 674) f. Decrees of 29 October 2016 (KHK/675 and 676) g. Decrees of 22 November 2016 (KHK/677 and 678) h. Decrees of 6 January 2017 (KHK/679, 680 and 681) i. Decrees of 23 January 2017 (KHK/682, 683, 684 and 685) j. Decree of 7 February 2017 (KHK/686) k. Decree of 9 February 2017 (KHK/687) l. Decree of 29 March 2017 (KHK/688) m. Decrees of 29 April 2017 (KHK/689 and 690) n. Decree of 22 June 2017 (KHK/691) o. Decree of 14 July 2017 (KHK/692) p. Decrees of 25 August 2017 (KHK/693 and 694) 3. 2016: Observations by the Council of Europe Committee, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression and the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission 4. January – September 2017: Observations by the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, the Council of Europe’s Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the Council of Europe, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression 5. -

Présidential Election in Estonia

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN ESTONIA 29th and 30th August 2011 European Elections monitor President of the Republic Toomas Hendrik Ilves is running for re-election as Head of Estonia from Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy The presidential election will take place on 29th and 30th August next in Estonia. The 101 members of the Riigikogu, the only chamber in Parliament, are being invi- ANALYSIS ted to appoint the new Head of State. Toomas Hendrik Ilves, the Head of State in 1 month before office, announced last December that he would be running for re-election. He has the poll the support of the Reform Party (ER) led by Prime Minister Andrus Ansip, the Pro Patria Union-Res Publica (IRL), member of the government coalition and the Social Democratic Party (SDE), T. Ilves’s party. The 23 MPs of the Pro Patria Union-Res Publica have 7) by the main opposition party, the Centre Party already signed a document expressing their support (KE), on 18th June last. Indrek Tarand is the son to the outgoing Head of State. “From our point of of former Prime Minister (1994-1995) and former view, thanks to his work, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, has MEP (2004-2009), Social Democrat, Andres Tarand. helped towards the development of civil society and In the last European elections on 4th-7th June 2009 has encouraged debate over problems that Estonia he stood as an independent and came second with has to face. The President of the Republic also suc- 25.81% of the vote, i.e. just behind the Centre Party ceeded in taking firm decisions during the crises that (26.07%) rallying a great number of protest votes the country experienced, such as for example, the to his name. -

Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Estonia, 1993-2001

Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg Wolfgang Zellner/Randolf Oberschmidt/Claus Neukirch (Eds.) Comparative Case Studies on the Effectiveness of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities Margit Sarv Integration by Reframing Legislation: Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Estonia, 1993-2001 Working Paper 7 Wolfgang Zellner/Randolf Oberschmidt/Claus Neukirch (Eds.) Comparative Case Studies on the Effectiveness of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities Margit Sarv∗ Integration by Reframing Legislation: Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Estonia, 1993-2001 CORE Working Paper 7 Hamburg 2002 ∗ Margit Sarv, M.Phil., studied Political Science at the Central European University in Budapest. Currently Ms. Sarv works as a researcher at the Institute of International and Social Studies in Tallinn. 2 Contents Editors' Preface 5 List of Abbreviations 6 Chapter 1. Introduction 8 Chapter 2. The Legacies of Soviet Rule: A Brief History of Estonian-Russian Relations up to 1991 11 Chapter 3. Estonia after Independence: The Radicalized Period from 1991 to 1994 19 3.1 From Privileges to Statelessness: The Citizenship Issue in Estonia in 1992 19 3.2 Estonia's Law on Citizenship and International Reactions 27 3.3 HCNM Recommendations on the Law on Citizenship of 1992 29 3.4 Language Training - the Double Responsibility Towards Naturalization and Integration 35 3.5 New Restrictions, -

Estonia As an International Actor in 2018: an Overview E-MAP Foundation MTÜ

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 13, No. 4 (EE) December 2018 Estonia external relations briefing: Estonia as an international actor in 2018: an overview E-MAP Foundation MTÜ 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 Estonia as an international actor in 2018: an overview Evidently, from the times when Estonia had been attempting to regain its independence back in 1990s, the country has never been more visible internationally than it has been during 2018. Partially, it was due to the factor of the centennial – while celebrating its big anniversary, Estonia seized the moment to ‘tell’ its comprehensive story to the world. At the same time, there were other factors, which ‘shaped’ the Estonian Republic’s actions on the international stage, and they could be singled out in the following three ‘baskets’ – the country’s application for the UN Security Council membership in 2020-2021 and its special attention paid to the Russian Federation’s aggressive stance in Europe. Estonia to the UN Security Council 2020-2021 Even though it was not a founding member of the organisation, Estonia managed to join the League of Nations in 1921, presumably anticipating its long-term active involvement in the complicated process of solving different issues of international significance. It did not go according to the plan, because the country had a bit less than 19 years of its existence as an independent state before it was occupied by the Soviet Union. -

Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine

ESTONIA IN SEPTEMBER 1988: STALINISTS, CENTRISTS AND RESTORATIONISTS Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine The situation in Estonia is changing beyond recognition by the month. A paper I gave in late April on this topic needed serious updating for an encore in early June and needs a complete rewrite now, in early September 1988.x By the rime it reaches the readers, the present article will be outdated, too. Either liberalization will have continued far beyond the present stage or a brutal back- lash will have cut it short. Is the scholar reduced to merely chronicling events? Not quite. There are three basic political currents that took shape a year ago and are likely to continue throughout further liberalization and even a crackdown. This framework will help to add analytical perspective to the chronicling. Political Forces in Soviet Estonia Broadly put, three political forces are vying for prominence in Estonia: Stalinists who want to keep the Soviet empire intact, perestroika-minded cen- trists whose goal is Estonia's sovereignty within a loose Soviet confederation, and restorationists who want to reestablish the pre-WWII Republic of Estonia. All three have appreciable support within the republic population. In many cases the same person is torn among all three: Emotionally he might yearn for the independence of the past, rationally he might hope only for a gradual for- marion of something new, and viscerally he might try to hang on to gains made under the old rules. (These gains include not only formal careers but much more; for instance, a skillful array of connections to obtain scarce consumer goods, lovingly built over a long time, would go to waste in an economy of plenty.) 1. -

Archipelagos, Edgelands, Imaginations

Peil, T 2021 A Town That Never Was – Archipelagos, Edgelands, Imaginations. Karib – Nordic Journal for Caribbean Studies, 6(1): 2, 1–10. DOI: https://doi. org/10.16993/karib.86 RESEARCH ARTICLE A Town That Never Was – Archipelagos, Edgelands, Imaginations Tiina Peil School of Culture and Learning, Södertörn University, SE [email protected] This article is an attempt at an interplay between Édouard Glissant’s archipelagic thinking, Marion Shoard’s edgeland and an imagined geography and history of a particular location and the people who have lived there. The town of Paldiski – the Baltic Port – bordering the Gulf of Finland, may be a remarkable Glissantian vantage point, and simultaneously an edgeland from which to draw attention to the creation and persistence of the ‘imaginaire’ that Glissant argued binds people as much as economic transactions. The port is both closed (as a military base or due to customs regulations) and open as a harbour. Thus, it frames all kinds of flows of peoples, materials and policies, yet it is on the edge literally and figuratively. In Paldiski, the imaginary seems independent of the physical environment, the past and future, and the people highlighted by the lifepaths of two historic figures. Keywords: edgeland; ethnicity; Paldiski (Baltic Port); Carl Friedrich Kalk; Salawat Yulayev Introduction This contribution is an Édouard Glissant-inspired investigation into a history and geography of a town – Paldiski on the Pakri Peninsula, the south coast of the Gulf of Finland, on the Baltic Sea – that never got to be the hub that it was envisioned to be, despite a multitude of efforts to create a superior military port, or at least a flourishing commercial centre in a location persistently argued to be ideal for such enterprise.1 This is not to say that there are no physical traces of a settlement in this particular spot but its assumed potential has been contained within a strictly defined outline and described persistently in similar terms despite numerous tumultuous changes in the physical environment and political system.