Swingin' Shakespeare from Harlem to Broadway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transgender Journey in Three Acts a PROJECT SUBMITTED to THE

Changes in Time: A Transgender Journey in Three Acts A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ethan Bryce Boatner IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2012 © Ethan Bryce Boatner 2012 i For Carl and Garé, Josephine B, Jimmy, Timothy, Charles, Greg, Jan – and all the rest of you – for your confidence and unstinting support, from both EBBs. ii BAH! Kid talk! No man is poor who can to what he likes to do once in a while! Scrooge McDuck ~ Only a Poor Old Man iii CONTENTS Chapter By Way of Introduction: On Being and Becoming ..…………………………………………1 1 – There Have Always Been Transgenders–Haven’t There? …………………………….8 2 – The Nosology of Transgenderism, or, What’s Up, Doc? …….………...………….….17 3 – And the Word Was Transgender: Trans in Print, Film, Theatre ………………….….26 4 – The Child Is Father to the Man: Life As Realization ………….…………...……....….32 5 – Smell of the Greasepaint, Roar of the Crowd ……………………………...…….……43 6 – Curtain Call …………………………………………………………………....………… 49 7 – Program ..………………………..……………………………….……………...………..54 8 – Changes in Time ....………………………..…………………….………..….……........59 Wishes ……………………………….………………….……………...…………………60 Dresses …………………………………………………….…………………….….…….85 Changes ………………………………………………………….….………..…………107 9 – Works Cited …………………….………………………………………....…………….131 1 By Way of Introduction On Being and Becoming “I think you’re very brave,” said G as the date for my public play-reading approached. “Why?” I asked. “It takes guts to come out like that, putting all your personal things out in front of everybody,” he replied. “Oh no,” I assured him. “The first six decades took guts–this is a piece of cake.” In fact, I had not embarked on the University of Minnesota’s Master of Liberal Studies (MLS) program with the intention of writing plays. -

2012 Hanne-Blank-Straight.Pdf

STRAIGHT THE SURPRISINGLY SHORT HISTORY OF HETEROSEXUALITY HANNE BLANK Beacon Press · Boston 2 For Malcolm 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Sexual Disorientation CHAPTER ONE The Love That Could Not Speak Its Name CHAPTER TWO Carnal Knowledge CHAPTER THREE Straight Science CHAPTER FOUR The Marrying Type CHAPTER FIVE What’s Love Got to Do with It? CHAPTER SIX The Pleasure Principle CHAPTER SEVEN Here There Be Dragons ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX 4 INTRODUCTION Sexual Disorientation Every time I go to the doctor, I end up questioning my sexual orientation. On some of its forms, the clinic I visit includes five little boxes, a small matter of demographic bookkeeping. Next to the boxes are the options “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual,” “transgender,” or “heterosexual.” You’re supposed to check one. You might not think this would pose a difficulty. I am a fairly garden-variety female human being, after all, and I am in a long-term monogamous relationship, well into our second decade together, with someone who has male genitalia. But does this make us, or our relationship, straight? This turns out to be a good question, because there is more to my relationship—and much, much more to heterosexuality—than easily meets the eye. There’s biology, for one thing. My partner was diagnosed male at birth because he was born with, and indeed still has, a fully functioning penis. But, as the ancient Romans used to say, barba non facit philosophum—a beard does not make one a philosopher. Neither does having a genital outie necessarily make one male. Indeed, of the two sex chromosomes—XY—which would be found in the genes of a typical male, and XX, which is the hallmark of the genetically typical female—my partner’s DNA has all three: XXY, a pattern that is simultaneously male, female, and neither. -

Music by Women TABLE of CONTENTS

Music by Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Ordering Information 2 Folk/Singer-Songwriter 58 Ladyslipper On-Line! * Ladyslipper Listen Line 4 Country 64 New & Recent Additions 5 Jazz 65 Cassette Madness Sale 17 Gospel 66 Cards * Posters * Grabbags 17 Blues 67 Classical 18 R&B 67 Global 21 Cabaret 68 Celtic * British Isles 21 Soundtracks 68 European 27 Acappella 69 Latin American 28 Choral 70 Asian/Pacific 30 Dance 72 Arabic/Middle Eastern 31 "Mehn's Music" 73 Jewish 31 Comedy 76 African 32 Spoken 77 African Heritage 34 Babyslipper Catalog 77 Native American 35 Videos 79 Drumming/Percussion 37 Songbooks * T-Shirts 83 Women's Spirituality * New Age 39 Books 84 Women's Music * Feminist * Lesbian 46 Free Gifts * Credits * Mailing List * E-Mail List 85 Alternative 54 Order Blank 86 Rock/Pop 56 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, 3205 Hillsborough Road. Durham NC 27705 USA PHONE ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat 10-6 Eastern Time) ORDERING INFO FAX ORDERS: 800-577-7892 INFORMATION: 919-383-8773 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.ladyslipper.org PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available: CD = compact disc, CS = cassette. Some schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives recordings are available only on CD or only on cassette, Ladyslipper, Inc. -

CD 64 Motion Poet Peter Erskine Erskoman (P. Erskine) Not a Word (P

Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 5/23/2011 JAZZ CD 64 Motion Poet Peter Erskine Erskoman (P. Erskine) Not a Word (P. Erskine) Hero with a Thousand Faces (V. Mendoza) Dream Clock (J. Zawinul) Exit up Right (P. Erskine) A New Regalia (V. Mendoza) Boulez (V. Mendoza) The Mystery Man (B. Mintzer) In Walked Maya (P. Erskine) CD 65 Real Life Hits Gary Burton Quartet Syndrome (Carla Bley) The Beatles (John Scofield) Fleurette Africaine (Duke Ellington) Ladies in Mercedes (Steve Swallow) Real Life Hits (Carla Bley) I Need You Here (Makoto Ozone) Ivanushka Durachok (German Lukyanov) CD 66 Tachoir Vision (Marlene Tachoir) Jerry Tachoir The Woods The Trace Erica’s Dream Township Square Ville de la Baie Root 5th South Infraction Gibbiance A Child’s Game CD 68 All Pass By (Bill Molenhof) Bill Molenhof PB Island Stretch Motorcycle Boys All Pass By New York Showtune Precision An American Sound Wave Motion CD 69 In Any Language Arthur Lipner & The Any Language Band Some Uptown Hip-Hop (Arthur Lipner) Mr. Bubble (Lipner) In Any Language (Lipner) Reflection (Lipner) Second Wind (Lipner) City Soca (Lipner) Pramantha (Jack DeSalvo) Free Ride (Lipner) CD 70 Ten Degrees North 2 Dave Samuels White Nile (Dave Samuels) Ten Degrees North (Samuels) Real World (Julia Fernandez) Para Pastorius (Alex Acuna) Rendezvous (Samuels) Ivory Coast (Samuels) Walking on the Moon (Sting) Freetown (Samuels) Angel Falls (Samuels) Footpath (Samuels) CD 71 Marian McPartland Plays the Music of Mary Lou Williams Marian McPartland, piano Scratchin’ in the Gravel Lonely Moments What’s Your Story, Morning Glory? Easy Blues Threnody (A Lament) It’s a Grand Night for Swingin’ In the Land of Oo Bla Dee Dirge Blues Koolbonga Walkin’ and Swingin’ Cloudy My Blue Heaven Mary’s Waltz St. -

Billy Tipton's Life As a Passing Woman by Danielle

Essay Award Winner 2002 The Man Who Played Well for a Woman: Billy Tipton’s Life as a Passing Woman by Danielle Picard Billy Tipton performed in a number of jazz and swing bands from the early 1930s onward as a vocalist and pianist, and according to a bandmate from the early days of Tipton’s career, “Billy was a fair sax man too, played very well for a woman.”[i][1] Some of the members of Tipton’s various bands, as well as some of the women who were considered his wives, never knew the secret revealed in this comment. Many of the people who knew and loved Tipton only learned on the occasion of his death in 1989 that he had been born female.[ii][2] Tipton is one of a large number of women in history who are now called “passing women” -- women who lived much of their lives as men.[iii][3] As in Billy’s case, the birth sex of these individuals was often a secret revealed only when they died. The lives of these women and of Billy Tipton in particular raise many questions about identity, gender, and sexuality, and these questions are not easily answered. Some historians have claimed Tipton and passing women in general as part of lesbian history while others see them as part of transsexual or transgender history; ultimately, it is impossible to determine which categorization is correct. Dorothy Lucille Tipton was born on December 29, 1914, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; BillyLee Tipton died in Spokane, Washington, on January 21, 1989. -

2021Translations-Program.Pdf

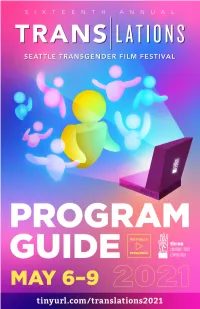

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME LETTER . .. 3 OPENING NIGHT FILM . 4 CLOSING NIGHT FILM . 5 FEATURES . 7–12 SHORTS . 14–22 EVENTS . 24–25 WELCOME LEttER WELCOME TO THE 16TH ANNUAL TRANSLATIONS! It is our great privilege to co-program the 16th annual Seattle Translations Festival, one of only ten festivals of its kind in the world. After years of elevating the voices of people who are rarely heard, it can feel like the change we need to bring about has arrived, particularly here in the openly liberal space of the Pacific Northwest. But as we all know, there is much work to be done. As we finalize our program, there are currently almost ninety pieces of anti-trans legislation being proposed across the US, and the horrific murder of trans folx, especially black trans women and trans women of color, occurs at alarming rates. While our struggles are not the same as in Brazil or Ukraine, where government sanctioned annihilation of trans and queer identified folx happens every day, it remains true that many of us here and around the world desperately need to know we are not alone. It is indeed a powerful act to see ourselves on screen, to tell our own stories, and to exist in community with each other. This is the work we do. For that, we are humbled and grateful. In the midst of so much darkness, we invite you to spend some time in the (spot)light and celebrate trans lives with us. We look forward to bringing you great films from around the world and to interacting with you online. -

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 131 SPRING 2014 CURTIS STIGERS UK £3.25 CONTENTS CURTIS STIGERS (PAGE 10) THE AMERICAN SINGER/SONGWRITER/SAXOPHONIST TALKS OF HIS VARIED CAREER IN MUSIC AHEAD OF THE RELEASE OF HIS LATEST CONCORD ALBUM, HOORAY FOR LOVE AND HIS APPEARANCES AT CHELTENHAM AND RONNIE SCOTT'S. 4 NEWS 5 UPCOMING EVENTS 7 LETTERS 8 HAPPY 100TH BIRTHDAY! SCOTT YANOW on jazz musicians born in 1914. 12 RETRIEVING THE MEMORIES Singer/collector/producer CHRIS ELLIS SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG looks back. THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED 15 MIDEM (PART 2) DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY £17.50* 16 JAZZ FESTIVALS Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your 20 JAZZ ARCHIVE/COMPETITIONS payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: 21 CD REVIEWS EU £20.50 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £24.50 Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC 29 BOOK REVIEWS Please send to: JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 BBC YOUNG MUSICIAN JAZZ AWARD Fax: 0121 454 9996 On March 8 the final of the first BBC Young Musician Jazz Award took place at the Email: [email protected] Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. The five finalists were three saxophonists Web: www.jazzrag.com (Sean Payne, Tom Smith and Alexander Bone), a trumpeter, Jake Labazzi, and a double bassist, Publisher / editor: Jim Simpson Freddie Jensen, all aged between 13 and 18. -

Narratives of Selfhood, Embodied Identities, And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Musical Performance and Trans Identity: Narratives of Selfhood, Embodied Identities, and Musicking A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Randy Mark Drake Committee in charge: Professor Timothy J. Cooley, Chair Professor David Novak Professor Mireille Miller-Young Professor George Lipsitz June 2018 The dissertation of Randy Mark Drake is approved. _____________________________________________ David Novak _____________________________________________ Mireille Miller-Young ____________________________________________________________ George Lipsitz _____________________________________________ Timothy J. Cooley, Committee Chair May 2018 Musical Performance and Trans Identity: Narratives of Selfhood, Embodied Identities, and Musicking Copyright © 2018 by Randy Mark Drake iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge Timothy Cooley, the chair of this dissertation and my advisor, for his gifts of guidance and his ability to encourage all of my academic endeavors. Tim has a passion for ethnomusicology, teaching, and writing, and he enjoys sharing his knowledge in ways that inspired me. He was always interested in my work and my performances. I am grateful for his gentle nudging and prodding regarding my writing. My first year at UCSB was also the beginning of a deep engagement with academic writing and thinking, and I had much to learn. Expanding my research boundaries was made simpler and more stimulating thanks to his consistent support and encouragement. I thank Tim for his mentorship, compassion, and kindness. David Novak never ceased amazing me with his intellectual curiosity and probing questions when it came to my own work. His dissertation workshop kept me focused on my research problems, and his tenacity in questioning those problems contributed greatly to my intellectual growth. -

11"1 a Queer Lliime Al"1A F?Lace General Editors: Jose Esteban Munoz and Ann Pellegrini

Judith Halberstam SEXUAL CULTURES: New Directions from the Center for lesbian and Gay Studies 11"1 a Queer lliime al"1a f?lace General Editors: Jose Esteban Munoz and Ann Pellegrini Transgender Bodies, Subcultural lives Times Square Red, Times Square Blue Samuel R. Delany Private Affairs: Critical Ventures in the Culture of Social Relations Phillip Brian Harper In Your Face: 9 Sexual Studies Mandy Merck Tropics of Desire: Interventions from Queer Latino America Jose Quiroga Murdering Masculinities: Fantasies of Gender and Violence in the American Crime Novel Greg Forter Our Monica, Ourselves: The Clinton Affair and the National Interest Edited by Lauren Berlant and Lisa Duggan Black Gay Man: Essays Robert Reid-Pharr Foreword by Samuel R. Delany Passing: Identity and Interpretation in Sexuality, Race, and Religion Edited by Maria Carla Sanchez and Linda Schlossberg The Queerest Art: Essays on Lesbian and Gay Theater Edited by Alisa Solomon and Framji Minwalla Queer Globalizations: Citizenship and the Afterlife of Colonialism Edited by Arnalda Cruz-Malave and Martin F. Manalansan IV Queer Latinidad: Identity Practices, Discursive Spaces Juana Maria Rodriguez love the Sin: Sexual Regulation and the Limits of Religious Tolerance Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture Frances Negr6n-Muntaner Manning the Race: Reforming Black Men in the Jim Crow Era Marlon B. Ross . Why I Hate Abercrombie &: Fitch: Essays on Race and Sexuality Dwight A. McBride In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender -

Genny Beemyn, "Transgender History in the United States"

2 Transgender History in the United States A special unabridged version of a book chapter from Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth GENNY BEEMYN TRANSGENDER HISTORY In thE UNITEd StATES by Genny Beemyn part of Trans Bodies, Trans Selves edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth AbOut thIs E-BOOK The history of transgender and gender nonconforming people in the United States is one of struggle, but also of self-determination and community building. Transgender groups have participated in activism and education around many issues, including gender expectations, depathologization, poverty, and discrimination. Like many other marginalized people, our history is not always preserved, and we have few places to turn to learn the stories of our predecessors. This chapter is an unabridged version of the United States History chapter of Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, a resource guide by and for transgender communities. Despite lim- iting its focus to the United States, this chapter still contained so much important in- formation that would need to be cut to meet the book’s length requirements that a decision was made to publish it separately in its original form. We cannot possibly tell the stories of the many diverse people who together make up our history, but we hope that this is a beginning. AbOut the AuthOR Genny Beemyn has published and spoken extensively on the experiences and needs of trans people, particularly the lives of gender nonconforming students. They have written or edited many books/journal issues, including The Lives of Transgender People (with Sue Rankin; Columbia University Press, 2011) and special issues of the Journal of LGBT Youth on “Trans Youth” and “Supporting Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Children and Youth” and a special issue of the Journal of Homosexuality on “LGBTQ Campus Experiences.” Genny’s most recent work is A Queer Capital: A History of Gay Life in Washington, D.C. -

0 SOL Jll I from SANDY THOMAS

The Transgender Community News & Information MoDthly #67 $7.00 AKING THE TRANSITION TO PRIME TIME TELEVISION ~GHTING BATTLES OF PREJUDICE ALONGSIDE THE GAY COMMUNITY WHY PROFESSIONALS DON'T UNDERSTAND US THE BILLy TIPTON PHENOMENON: A FEMALE MAN 67 BSERVATION IN GEND ER ROLE DEVELOPMENT ~ASSING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER ONE PERSON'S EXPERIENCE WITH HORMONES NEWS ... INFORMATION ... COMMENTARY ... HUMOR 0 SOL Jll I FROM SANDY THOMAS CONTEl\IPORARY lV FICTION # 20 is " I DRESS, THE R EFOR E I AJ\J." CONTEMPORARY ( TV FICTION CLASStcD TV FICTION This double issue is by a new, talented a uthor and is about a young man getting caught MACADN( by his mother. To his surpr ise sh e offers to buy him a dress and more! I loved it! TV FICT ION CLASSICS# 37 is "CA1\ IPI G I CUR LS." This d ouble issue is about a fa mily th at sends their son to camp because he has feminine tendencies. The camp teaches him ever)1hing about being a girl! I mean evcr)1hing! Also new is the S ISSY l\IAID Q UARTERLY # 3. This is better than ever with arti cles o n Gaffs, Panties, Ladies maids and fashion! SOMETlllNG ORAND NEW! l VFIC flONSllOWC \SE ll I. TOl\IBOYSis about two soccer mad boys. One has to wear his sistcr ·s hand-me-downs. T his book was completely put together by a reader. T his new series will bring you new \\Titers. differ cnt type sto ries. short pieces, illustrations. pictu res. tho ugh ts, poems, whatever YOU send anJ is good . -

Teaching Jazz As American Culture Lesson Plans

TEACHING JAZZ AS AMERICAN CULTURE LESSON PLANS NEH SUMMER INSTITUTE The Center for the Humanities Washington University in St. Louis July 5-29, 2005 T ABLE OF CON T EN T S Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................v Jazz and the City Lesson Plan One: Jazz in the City: Migration .........................................................................................3 Lesson Plan Two: Jazz in the City: Introduction .....................................................................................6 Lesson Plan Three: Jazz in the American Cities .....................................................................................9 Lesson Plan Four: Interrelated Urban Societal Influences on Jazz (Jazz and the Cities) .......................12 Lesson Plan Five: Jazz History Through American Cities ....................................................................14 Lesson Plan Six: Jazz and the City .........................................................................................................19 Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement Lesson Plan One: Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement ........................................................................23 Lesson Plan Two: Jazz as a Social Movement .......................................................................................25 Lesson Plan Three: Jazz and Civil Rights .............................................................................................27