English Cop18 Inf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trade in Tokay Geckos in South-East Asia

Published by TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2013 TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF AND IUCN. Layout by Olivier S Caillabet, TRAFFIC Suggested citation: Olivier S. Caillabet (2013). The Trade in Tokay Geckos Gekko gecko in South-East Asia: with a case study on Novel Medicinal Claims in Peninsular Malaysia TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 978-983-3393-36-7 Photograph credit Cover: Tokay Gecko in Northern Peninsular Malaysia (C. Gomes/TRAFFIC) The Trade in Tokay Geckos Gekko gecko in South-East Asia: with a case study on Novel Medicinal Claims in Peninsular Malaysia Olivier S. Caillabet © O.S. Caillabet/TRAFFIC A pet shop owner in Northern Peninsular Malaysia showing researchers a Tokay Gecko for sale TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements -

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

Tokay Gecko Glossary the Tokay Gecko Is Recommended for Experienced Reptile - a Cold-Blooded Vertebrate with Scaly Skin

Tokay Gecko Glossary The Tokay gecko is recommended for experienced Reptile - A cold-blooded vertebrate with scaly skin. keepers. They are closely related to the palm gecko Amphibian - A cold-blooded vertebrate that begins life but are much more aggressive. They can be tamed as an aquatic animal and grows into a terrestrial adult but it is not easy. They are the second largest gecko with lungs. species in the world, second only to the New Terrestrial - A ground dwelling animal. Caledonian Giant Gecko. Generally their colouration Arboreal - An animal that lives in trees. ranges between blue to grey with yellow or red spots. Diurnal - Awake in the day. Tokay Their life span is between 8-10 years. Females can Nocturnal- Awake during the night. potentially be housed together or with one male. UVB - Ultraviolet radiaton. Gecko Males cannot be housed together. Colubrid - A family of snakes. Hybrid - Offspring from animals of different species. Morph - Colourations created due to genetics. Musk - Unpleasant odour released when an animal is stressed or feels threatened. Live plants are only available on special order If you require any further information, please ask our pet care advisors who will be very happy to help. Opening Times Monday - Saturday: 9am - 6pm Sunday: 9.30am - 4pm Chessington Garden Centre Leatherhead Road, Chessington, Surrey, KT9 2NG Care & Advice Sheet Tel: 01372 725 638 Email: [email protected] Web: www.chessingtongardencentre.co.uk Please recycle me once you’ve nished reading. Inspiration for your Home & Garden Substrate & Furnishings Food & Water Newspaper and kitchen towel can be used as they These geckos eat mainly live food such as: are easy to replace. -

Opportunistic Feeding by House-Dwelling Geckos: Does This Make Them More Successful Invaders?

The Herpetological Bulletin 149, 2019: 38-40 SHORT COMMUNICATION https://doi.org/10.33256/hb149.3840 Opportunistic feeding by house-dwelling geckos: does this make them more successful invaders? ROBBIE WETERINGS1* & PREEYAPORN WETERINGS1 1 Cat Drop Foundation, Drachten, Netherlands *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Abstract - Various species of ‘house’ gecko are found in and around buildings, where they can be observed feeding opportunistically on the insects attracted to artificial lights. Most of the species are considered strict insectivores. Nevertheless, there have been several recently published observations of ‘house’ geckos feeding on non-insect food. In order to assess how common this behaviour is among geckos worldwide, we offered an online questionnaire to ecologists and herpetologists. Of the 74 observations received, most reported Hemidactylus frenatus, H. platyurus and Gehyra mutilata feeding on rice, bread, fruits, vegetables, dog food or chocolate cream, taken from tables, plates, and garbage bins. This opportunistic feeding behaviour is much more common than previously thought and is perpetrated by species considered to be highly invasive, possibly contributing to their success as invaders. INTRODUCTION 2. What did the gecko consume? a. Insects or other invertebrates everal gecko species (e.g. Hemidactylus frenatus and b. Fruit or vegetables SGehyra mutilata) are often found in and around houses. c. Rice These, so-called ‘house’ geckos, are very well adapted to d. Bread urban life and are often observed feeding opportunistically e. Eggs on insects attracted to artificial lights at night (Tkaczenko f. Unsure et al., 2014). This provides them an easily accessible food g. Other... source in locations generally lacking predators. -

Three New Exotic Gecko Species Identified on Curaçao

Three new exotic gecko species identified on Curaçao By Jocelyn Behm (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Temple University) As part of the Caribbean Island Biogeography were known to have breeding populations it was found in Cuba. It is now present in the While they were processing their genetic samples, meets the Anthropocene project, researchers on Curaçao. Bahamas, Grand Cayman Island, Guadeloupe, and Gerard van Buurt received a notification that the initiated their surveys for exotic reptile and Curaçao. Upon discussions with their collaborator, exotic Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) was found in the amphibian species on Curaçao. They found three The research team conducted day and evening Gerard van Buurt, he reviewed older photographs Santa Catharina neighborhood of Curaçao. The new exotic gecko species on Curaçao, which surveys island-wide to confirm the presence of and identified a mourning gecko in a photo L’Aldea restaurant has a small display of animals may have negative implications for Curaçao’s these exotic species and potentially identify new taken in 2009. Therefore, they know it has been to entertain visitors including the Tokay gecko, three native gecko species and species. Often exotic species are found more in established on Curaçao for nearly a decade. and apparently juvenile geckos escaped from this native ecosystems. developed areas than natural habitats, so they enclosure and established a breeding population searched both natural areas (e.g., Christoffel, The second species the team discovered is the in the neighborhood. The captive Tokay geckos Exotic species, species introduced to a new Kabouterbos), and developed areas (e.g., resorts, Asian house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus). -

Clues to the Past and Inspiration for the Future by Gregory D

MODEL OF THE MONTH Clues to the past and inspiration for the future by Gregory D. Larsen vision3. These traits are common and specialized among different Scientific name gecko species, though rare among other lizards, and their various Gekko gecko forms might hold clues as to how these complex senses evolved in TaxOnOmy other lineages of terrestrial vertebrates. PHYLUM: Chordata Like many reptiles and amphibians, geckos can sever their own ClASS: Reptilia tails and grow a similar replacement. Although the new tail is not a complete replica, it reflects regenerative capabilities far superior OrDEr: Squamata to those of most non-reptilian amniotes1. Many researchers have FAmIly: Gekkonidae therefore investigated the mechanisms of the underlying process, hoping that they might advance regenerative medicine in humans. Geckos are perhaps best known for their ability to scale and grip Physical description nearly any surface, which has inspired many studies and The Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) is a inventions in recent years. Many gecko species nocturnal arboreal lizard whose possess adhesive pads on their toes, which native range spans the rainforests are covered in keratinous setae made of south and s outheast Asia, up of hundreds of 200-nm spatu- from India through New lae4. As a gecko walks along a Guinea. Tokay geckos are surface, these spatulae flat- one of the largest gecko ten against the substrate species, growing up to 51 cm material and form weak p u o in length and w eighing up to r chemical bonds through G g Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved. America, Inc. Nature n 400 g. -

Tokay Gecko Reptile Gekko Gecko

Tokay Gecko Reptile Gekko gecko Scientific Name Gekko gecko Other Names None Range Native to Southeast Asia, Philippines, Indonesia and western New Guinea Habitat Tropical rainforest Average Size Length: 11 - 15 in. Weight: 250 – 350 g. Behavior Tokay Geckos are solitary and nocturnal lizards that only come together Description during mating season. They are extremely territorial and aggressive and A large lizard with a blue-gray body covered will vigorously defend their territory against intruders with sharp teeth in reddish-orange spots. capable of inflicting severe and powerful bites. Tokay Geckos make a variety of sounds including hisses, squeaks, whistles, growls and barks that serve as communication, to finding members of the opposite sex during the Diet breeding season, and as a means of warning or defense. In the wild: Insects In captivity: Insects An important characteristic of the Tokay Gecko is its ability to cast off its tail in defense and regenerate a new one. The tail has several sections where it can break; the part of the tail that has been cast off will continue to move Lifespan violently for several minutes, giving the gecko time to escape. It takes In the wild: Estimated at 10 years about three weeks for these geckos to completely regenerate a new tail, In captivity: Up to 15 years but it is rarely as long as the original. Incubation These arboreal lizards move easily through the trees using flattened toe 200 days pads that are covered with dead, keratinized scales called lamellae. The lamellae scale surface is made up of long hair-like structures called setae, with each seta being divided and subdivided along its length. -

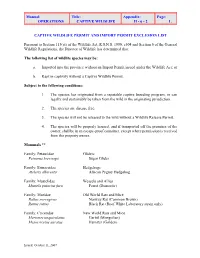

Captive Wildlife Exclusion List

Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 1. CAPTIVE WILDLIFE PERMIT AND IMPORT PERMIT EXCLUSION LIST Pursuant to Section 113(at) of the Wildlife Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c504 and Section 6 of the General Wildlife Regulations, the Director of Wildlife has determined that: The following list of wildlife species may be: a. Imported into the province without an Import Permit issued under the Wildlife Act; or b. Kept in captivity without a Captive Wildlife Permit. Subject to the following conditions: 1. The species has originated from a reputable captive breeding program, or can legally and sustainably be taken from the wild in the originating jurisdiction. 2. The species are disease free. 3. The species will not be released to the wild without a Wildlife Release Permit. 4. The species will be properly housed, and if transported off the premises of the owner, shall be in an escape-proof container, except where permission is received from the property owner. Mammals ** Family: Petauridae Gliders Petuarus breviceps Sugar Glider Family: Erinaceidae Hedgehogs Atelerix albiventis African Pygmy Hedgehog Family: Mustelidae Weasels and Allies Mustela putorius furo Ferret (Domestic) Family: Muridae Old World Rats and Mice Rattus norvegicus Norway Rat (Common Brown) Rattus rattus Black Rat (Roof White Laboratory strain only) Family: Cricetidae New World Rats and Mice Meriones unquiculatus Gerbil (Mongolian) Mesocricetus auratus Hamster (Golden) Issued: October 11, 2007 Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 2. Family: Caviidae Guinea Pigs and Allies Cavia porcellus Guinea Pig Family: Chinchillidae Chinchillas Chincilla laniger Chinchilla Family: Leporidae Hares and Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus European Rabbit (domestic strain only) Birds Family: Psittacidae Parrots Psittaciformes spp.* All parrots, parakeets, lories, lorikeets, cockatoos and macaws. -

Captive Wildlife Allowed List

Saskatchewan Captive Wildlife Allowed Species List (as of June 1, 2021) AMPHIBIANS (CLASS AMPHIBIA) Class (Common Name) Scientific Name Family Ambystomatidae Axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum Marble Salamander Ambystoma opacum Family Bombinatoridae Oriental Fire-Bellied Toad Bombina orientalis Family Bufonidae Green Toad Anaxyrus debilis Black Indonesian Toad Bufo asper Indonesian Toad Duttaphrynus melanostictus Family Ceratophryidae Surinam Horned Frog Ceratophrys cornuta Chacoan Horned Frog Ceratophrys cranwelli Argentine Horned Frog Ceratophrys ornata Budgett’s Frog Lepidobatrachus laevis Family Dendrobatidae Dart Poison Frog Dendrobates auratus Yellow-banded Poison Dart Frog Dendrobates leucomelas Dyeing Dart Frog Dendrobates tinctorius Yellow-striped Poison Frog Dendrobates truncatus Family Hylidae Clown Tree Frog Dendropsophus leucophyllatus Bird Poop Tree Frog Dendropsophus marmoratus Barking Tree Frog Dryophytes gratiosus Squirrel Tree Frog Dryophytes squirellus Green Tree Frog Dryophytes cinereus Cuban Tree Frog Osteopilus septentrionalis Haitian Giant Tree Frog Osteopilus vastus White’s Tree Frog Ranoidea caerulea Brazilian Black and White Milky Frog Trachycephalus resinifictrix Hyperoliidae African Reed Frog Hyperolius concolor Family Mantellidae Baron’s Mantella Mantella baroni Brown Mantella Mantella betsileo Family Megophryidae Long-nosed Horned Frog Megophrys nasuta Family Microhylidae Tomato Frog Dyscophus guineti Chubby Frog Kaloula pulchra Banded Rubber Frog Phrynomantis bifasciatus Emerald Hopper Frog Scaphiophryne madagascariensis -

Genetic Structure of the Red-Spotted Tokay Gecko, Gekko Gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Mainland Southeast Asia

Asian Herpetological Research 2019, 10(2): 69–78 ORIGINAL ARTICLE DOI: 10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.180066 Genetic Structure of the Red-spotted Tokay Gecko, Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Mainland Southeast Asia Weerachai SAIJUNTHA1, Sutthira SEDLAK1, Takeshi AGATSUMA2, Kamonwan JONGSOMCHAI3, Warayutt PILAP1, Watee KONGBUNTAD4, Wittaya TAWONG5, Warong SUKSAVATE1, Trevor N. PETNEY6 and Chairat TANTRAWATPAN7* 1 Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Biodiversity and Conservation Research Unit, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand 2 Department of Environmental Medicine, Kochi Medical School, Kochi University, Oko, Nankoku, Kochi 783-8505, Japan 3 Department of Anatomy, School of Medical Science, Phayao University, Phayao 56000, Thailand 4 Program in Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Maejo University, Chiang Mai 50290, Thailand 5 Department of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok 65000, Thailand 6 Department of Paleontology and Evolution, State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe, Erbprinzenstrasse 13, Karlsruhe 76133, Germany 7 Division of Cell Biology, Department of Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Rangsit Campus, Pathumthani 12120, Thailand Abstract This study was performed to explore the genetic diversity and genetic structure of red-spotted tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) from 23 different geographical areas in Thailand, Lao PDR and Cambodia. The mitochondrial tRNA- Gln/tRNA-Met/partial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 from 166 specimens was amplified and sequenced. A total of 54 different haplotypes were found. Highly significant genetic differences occurred between populations from different localities. The haplotype network revealed six major haplogroups (G1 to G6) belonging to different clades (clade A– E). Clade D and clade E were newly observed in this study. -

Gekko Gecko) Eggs Glued to a Wooden Beam CONSERVATION RESEARCH REPORTS: Summaries of Publishedin Pandau, Conservation Ilam Research District, Reports Nepal

HTTPS://JOURNALS.KU.EDU/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSREPTILES • VOL & AMPHIBIANS15, NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 28(2):189 312–313 • AUG 2021 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS TailFEATURE Bifurcation ARTICLES in a Tokay Gecko, Gekko . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: geckoOn the (Linnaeus Road to Understanding the Ecology and 1758), Conservation of the Midwest’s with Giant Serpent ......................Notes Joshua M. Kapferon 190 the . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: NaturalA Hypothetical History Excursion ............................................................................................................................ of the Species in RobertIlam, W. Henderson 198Nepal RESEARCH ARTICLES . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas .......................Tapil P. Rai Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida Department of Environmental ............................................. Science, Mechi MultipleBrian J. Camposano, Campus, Kenneth Bhadrapur L. Krysko, Municipality-8, Kevin M. Enge, Jhapa, Ellen M.Nepal, Donlan, and and the Michael Turtle Granatosky Rescue and 212 Conservation Centre (TRCC), Arjundhara Municipality-9, Jhapa, Nepal ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Correlophus Ciliatus

Correlophus ciliatus The crested gecko (Correlophus ciliatus) is a species of gecko native to southern New Caledonia. In 1866, the crested gecko was discovered by a French zoologist named Alphone Guichenot, who is also credited with naming the species.[2] This species was thought extinct until it was rediscovered in 1994 during an expedition led by Robert Seipp.[3][4] Along with several Rhacodactylus species, it is being considered for protected status by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. It is popular in the pet trade. Taxonomy The species was first described in 1866 as Correlophus ciliatus by the French zoologist Alphone Guichenot in an article Vulnerable (IUCN 3.1)[1] entitled "Notice sur un nouveau genre de sauriens de la famille des geckotiens du Muséum de Paris" ("Notes on a new species Scientific Classification of lizard in the gecko family") in the Mémoires de la Société Scientifique Naturelle de Chérbourg. It was later Kingdom: Anamalia renamed Rhacodactylus ciliatus. Recent phylogenetic Phylum: Cordata analysis indicates that R. ciliatus and R. sarasinorum are not closely related to the other giant geckos, so these two species Class: Reptilia have been moved back to the genus Correlophus.[5] Order: Squamata Suborder: Serpentes The specific name, ciliatus, is Latin, from cilia ("fringe" or Family: Diplodactylidae "eyelashes") and refers to the crest of skin over the animal's Geunus Correlophus eyes that resembles eyelashes. Species C.ciliatus Physical description Binomial Name Correlophus ciliatus Guichenot, 1866 This captive crested gecko has a tricolor extreme harlequin pattern that is not found in the wild.