Medicinal Use of Gekko Gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae) Has an Impact on Agamid Lizards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Relationships and Subgeneric Taxonomy of Toad�Headed Agamas Phrynocephalus (Reptilia, Squamata, Agamidae) As Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing E

ISSN 00124966, Doklady Biological Sciences, 2014, Vol. 455, pp. 119–124. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2014. Original Russian Text © E.N. Solovyeva, N.A. Poyarkov, E.A. Dunayev, R.A. Nazarov, V.S. Lebedev, A.A. Bannikova, 2014, published in Doklady Akademii Nauk, 2014, Vol. 455, No. 4, pp. 484–489. GENERAL BIOLOGY Phylogenetic Relationships and Subgeneric Taxonomy of ToadHeaded Agamas Phrynocephalus (Reptilia, Squamata, Agamidae) as Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing E. N. Solovyeva, N. A. Poyarkov, E. A. Dunayev, R. A. Nazarov, V. S. Lebedev, and A. A. Bannikova Presented by Academician Yu.Yu. Dgebuadze October 25, 2013 Received October 30, 2013 DOI: 10.1134/S0012496614020148 Toadheaded agamas (Phrynocephalus) is an essen Trapelus, and Stellagama) were used in molecular tial element of arid biotopes throughout the vast area genetic analysis. In total, 69 sequences from the Gen spanning the countries of Middle East and Central Bank were studied, 28 of which served as outgroups (the Asia. They constitute one of the most diverse genera of members of Agamidae, Chamaeleonidae, Iguanidae, the agama family (Agamidae), variously estimated to and Lacertidae). comprise 26 to 40 species [1]. The subgeneric Phryno The fragment sequences of the following four cephalus taxonomy is poorly studied: recent taxo mitochondrial DNA genes were used in phylogenetic nomic revision have been conducted without analysis analysis: the genes of subunit I of cytochrome c oxi of the entire genus diversity [1]; therefore, its phyloge dase (COI), of subunits II and IV of NADHdehydro netic position within Agamidae family remains genase (ND2 and ND4), and of cytochrome b (cyt b). -

Ggt's Recommendations on the Amendment Proposals for Consideration at the Eighteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties

GGT’S RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE AMENDMENT PROPOSALS FOR CONSIDERATION AT THE EIGHTEENTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES TO CITES For the benefit of species and people (Geneva, 2019) ( GGT’s motto ) A publication of the Global Guardian Trust. 2019 Global Guardian Trust Higashikanda 1-2-8, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-0031 Japan GLOBAL GUARDIAN TRUST GGT’S RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE AMENDMENT PROPOSALS FOR CONSIDERATION AT THE EIGHTEENTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES TO CITES (Geneva, 2019) GLOBAL GUARDIAN TRUST SUMMARY OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS Proposal Species Amendment Recommendation 1 Capra falconeri heptneri markhor I → II Yes 2 Saiga tatarica saiga antelope II → I No 3 Vicugna vicugna vicuña I → II Yes 4 Vicugna vicugna vicuña annotation Yes 5 Giraffa camelopardalis giraffe 0 → II No 6 Aonyx cinereus small-clawed otter II → I No 7 Lutogale perspicillata smooth-coated otter II → I No 8 Ceratotherium simum simum white rhino annotation Yes 9 Ceratotherium simum simum white rhino I → II Yes 10 Loxodonta africana African elephant I → II Yes 11 Loxodonta africana African elephant annotation Yes 12 Loxodonta africana African elephant II → I No 13 Mammuthus primigenius wooly mammoth 0 → II No 14 Leporillus conditor greater stick-nest rat I → II Yes 15 Pseudomys fieldi subsp. Shark Bay mouse I → II Yes 16 Xeromys myoides false swamp rat I → II Yes 17 Zyzomys pedunculatus central rock rat I → II Yes 18 Syrmaticus reevesii Reeves’s pheasant 0 → II Yes 19 Balearica pavonina black crowned crane II → I No 20 Dasyornis broadbenti rufous bristlebird I → II Yes 21 Dasyornis longirostris long-billed bristlebird I → II Yes 22 Crocodylus acutus American crocodile I → II Yes 23 Calotes nigrilabris etc. -

Fossil Amphibians and Reptiles from the Neogene Locality of Maramena (Greece), the Most Diverse European Herpetofauna at the Miocene/Pliocene Transition Boundary

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Fossil amphibians and reptiles from the Neogene locality of Maramena (Greece), the most diverse European herpetofauna at the Miocene/Pliocene transition boundary Georgios L. Georgalis, Andrea Villa, Martin Ivanov, Davit Vasilyan, and Massimo Delfino ABSTRACT We herein describe the fossil amphibians and reptiles from the Neogene (latest Miocene or earliest Pliocene; MN 13/14) locality of Maramena, in northern Greece. The herpetofauna is shown to be extremely diverse, comprising at least 30 different taxa. Amphibians include at least six urodelan (Cryptobranchidae indet., Salamandrina sp., Lissotriton sp. [Lissotriton vulgaris group], Lissotriton sp., Ommatotriton sp., and Sala- mandra sp.), and three anuran taxa (Latonia sp., Hyla sp., and Pelophylax sp.). Rep- tiles are much more speciose, being represented by two turtle (the geoemydid Mauremys aristotelica and a probable indeterminate testudinid), at least nine lizard (Agaminae indet., Lacertidae indet., ?Lacertidae indet., aff. Palaeocordylus sp., ?Scin- cidae indet., Anguis sp., five morphotypes of Ophisaurus, Pseudopus sp., and at least one species of Varanus), and 10 snake taxa (Scolecophidia indet., Periergophis micros gen. et sp. nov., Paraxenophis spanios gen. et sp. nov., Hierophis cf. hungaricus, another distinct “colubrine” morphotype, Natrix aff. rudabanyaensis, and another dis- tinct species of Natrix, Naja sp., cf. Micrurus sp., and a member of the “Oriental Vipers” complex). The autapomorphic features and bizarre vertebral morphology of Perier- gophis micros gen. et sp. nov. and Paraxenophis spanios gen. et sp. nov. render them readily distinguishable among fossil and extant snakes. Cryptobranchids, several of the amphibian genera, scincids, Anguis, Pseudopus, and Micrurus represent totally new fossil occurrences, not only for the Greek area, but for the whole southeastern Europe. -

The Results of Four Recent Joint Expeditions to the Gobi Desert: Lacertids and Agamids

Russian Journal of Herpetology Vol. 28, No. 1, 2021, pp. 15 – 32 DOI: 10.30906/1026-2296-2021-28-1-15-32 THE RESULTS OF FOUR RECENT JOINT EXPEDITIONS TO THE GOBI DESERT: LACERTIDS AND AGAMIDS Matthew D. Buehler,1,2* Purevdorj Zoljargal,3 Erdenetushig Purvee,3 Khorloo Munkhbayar,3 Munkhbayar Munkhbaatar,3 Nyamsuren Batsaikhan,4 Natalia B. Ananjeva,5 Nikolai L. Orlov,5 Theordore J. Papenfuss,6 Diego Roldán-Piña,7,8 Douchindorj,7 Larry Lee Grismer,9 Jamie R. Oaks,1 Rafe M. Brown,2 and Jesse L. Grismer2,9 Submitted March 3, 2018 The National University of Mongolia, the Mongolian State University of Education, the University of Nebraska, and the University of Kansas conducted four collaborative expeditions between 2010 and 2014, resulting in ac- counts for all species of lacertid and agamid, except Phrynocephalus kulagini. These expeditions resulted in a range extension for Eremias arguta and the collection of specimens and tissues across 134 unique localities. In this paper we summarize the species of the Agamidae (Paralaudakia stoliczkana, Ph. hispidus, Ph. helioscopus, and Ph. versicolor) and Lacertidae (E. argus, E. arguta, E. dzungarica, E. multiocellata, E. przewalskii, and E. vermi- culata) that were collected during these four expeditions. Further, we provide a summary of all species within these two families in Mongolia. Finally, we discuss issues of Wallacean and Linnaean shortfalls for the herpetofauna of the Mongolian Gobi Desert, and provide future directions for studies of community assemblages and population genetics of reptile species in the region. Keywords: Mongolia; herpetology; biodiversity; checklist. INTRODUCTION –15 to +15°C (Klimek and Starkel, 1980). -

The Trade in Tokay Geckos in South-East Asia

Published by TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2013 TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF AND IUCN. Layout by Olivier S Caillabet, TRAFFIC Suggested citation: Olivier S. Caillabet (2013). The Trade in Tokay Geckos Gekko gecko in South-East Asia: with a case study on Novel Medicinal Claims in Peninsular Malaysia TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 978-983-3393-36-7 Photograph credit Cover: Tokay Gecko in Northern Peninsular Malaysia (C. Gomes/TRAFFIC) The Trade in Tokay Geckos Gekko gecko in South-East Asia: with a case study on Novel Medicinal Claims in Peninsular Malaysia Olivier S. Caillabet © O.S. Caillabet/TRAFFIC A pet shop owner in Northern Peninsular Malaysia showing researchers a Tokay Gecko for sale TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements -

On the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 631-637 (2020) (published online on 05 August 2020) An update to species distribution records of geckos (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae) on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal Ashwini V. Mohan1,2,* The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are rifted arc-raft of 2004, and human-mediated transport can introduce continental islands (Ali, 2018). Andaman and Nicobar additional species to these islands (Chandramouli, 2015). Islands together form the largest archipelago in the In this study, I provide an update for the occurrence Bay of Bengal and a high proportion of terrestrial and distribution of species in the family Gekkonidae herpetofauna on these islands are endemic (Das, 1999). (geckos) on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Although often lumped together, the Andamans and Nicobars are distinct from each other in their floral Materials and Methods and faunal species communities and are geographically Teams consisted of between 2–4 members and we separated by the 10° Channel. Several studies have conducted opportunistic visual encounter surveys in shed light on distribution, density and taxonomic accessible forested and human-modified areas, both aspects of terrestrial herpetofauna on these islands during daylight hours and post-sunset. These surveys (e.g., Das, 1999; Chandramouli, 2016; Harikrishnan were carried out specifically for geckos between and Vasudevan, 2018), assessed genetic diversity November 2016 and May 2017, this period overlapped across island populations (Mohan et al., 2018), studied with the north-east monsoon and summer seasons in the impacts of introduced species on herpetofauna these islands. A total of 16 islands in the Andaman and and biodiversity (e.g., Mohanty et al., 2016a, 2019), Nicobar archipelagos (Fig. -

Occurrence of the Tokay Gecko Gekko Gecko (Linnaeus 1758) (Squamata, Gekkonidae), an Exotic Species in Southern Brazil

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 8-10 (2015) (published online on 26 January 2015) Occurrence of the Tokay Gecko Gekko gecko (Linnaeus 1758) (Squamata, Gekkonidae), an exotic species in southern Brazil José Carlos Rocha Junior1,*, Alessandher Piva2, Jocassio Batista3 and Douglas Coutinho Machado4 The Tokay gecko Gekko gecko (Linnaeus 1758) is a (Henderson et al., 1993), Hawaii, Florida (Kraus, lizard of the Gekkonidae family (Gamble et al., 2008) 2009a), Belize (Caillabet, 2013) and Madagascar whose original distribution is limited to China, India, (Lever, 2003). In Taiwan, the species has been reported Indonesia, Indochina (Cambodia and Laos), Malaysia, to occur in the wilderness, but it is unknown whether Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and these are naturally occurring (i.e., isolated population) Vietnam (Denzer and Manthey, 1991; Means, 1996; or introduced populations (Norval et al., 2011). Species Grossmann, 2004; Rösler, 2005; Das, 2007; Rösler et introduction events are known to occur via the poultry al., 2011). Gekko gecko is a generalist species, inhabiting trade, and have also been reported to occur through both natural and altered environments (Nabhitabhata and transportation on cargo ships (Wilson and Porras, 1983; Chan-ard, 2005; Lagat, 2009) and feeding on a variety Caillabet, 2013). Impacts from alien herpetofauna, have of prey, such as: arachnids, centipedes, crustaceans, been affecting humans (e.g., social impact) and native beetles, longhorn beetles, ants, moths, gastropods, species (e.g., ecological and evolutionary impacts) dragonflies, damselflies, termites, vertebrates and skins (Kraus, 2009b). (Meshaka et al., 1997; Aowphol et al., 2006; Bucol and On January 6, 2008 we recorded an individual Gekko Alcala, 2013). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

SYLLABUS for B. Sc. ZOOLOGY (HONOURS & GENERAL) 2016

SYLLABUS FOR B. Sc. ZOOLOGY (HONOURS & GENERAL) 2016 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA Page 1 of 25 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA DRATF SYLLABUS FOR B. Sc. ZOOLOGY (HONOURS & GENERAL) 2016 Marks No. of . Unit Group Topic . Classes Paper Paper Gr Tot PART – I HONOURS Group A Diversity & Functional Anatomy of Non-chordate Forms 25 Unit I 75 50 Group B Diversity & Functional Anatomy of Chordate Forms 25 Group A Cell biology 15 Paper 1 Paper Unit II 75 50 Group B Genetics 35 Unit I 75 Developmental Biology 50 Animal forms and Comparative anatomy, Cytological methods and Unit II 75 Practical 50 Paper 2 Paper Genetics, Osteology and Embryology PART – II HONOURS Group A Systematics 15 Unit I 75 Group B Evolutionary Biology & Adaptation 25 50 Group C Animal Behaviour 10 Paper 3 Paper Group A Ecology 25 Unit II 75 50 Group B Biodiversity and Conservation 25 Group A Animal physiology 25 Unit I 75 50 Group B Biochemistry 25 Paper 4 Paper Ecological methods, Systematics and Evolutionary Biology, Animal Unit II 75 Practical 50 Physiology and Biochemistry PART – III HONOURS Unit I 75 Molecular Biology 50 Group A Parasitology and Microbiology 25 Unit II 75 50 Paper 5 Paper Group B Immunology 25 Unit I 75 Integration Biology and Homeostasis 50 Paper 6 Paper Unit II 75 Animal Biotechnology & Applied Zoology 50 Molecular biology, Parasitology and Microbiology, Immunology, Histological Practical 75 100 techniques and staining methods, Adaptation Paper 7 Paper Instrumentation, Report on Environmental audit, Field work assessment, Practical 75 100 Biostatistics Paper 8 Paper Page 2 of 25 PART - I (PAPER 1: UNIT I) (Diversity & Functional Anatomy of Non-chordate & Chordate Forms) [Note: Classification will be dealt in practical section of the course] Group A: Non chordate Marks = 25 1. -

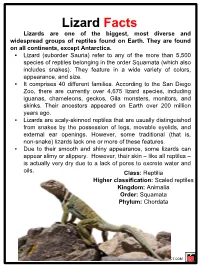

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

English Cop18 Inf

Original language: English CoP18 Inf. 21 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Geneva (Switzerland), 17-28 August 2019 INFORMATION SUPPORTING PROPOSAL COP18 PROP. 28, TO INCLUDE GEKKO GECKO IN APPENDIX II, AS SUBMITTED BY THE EUROPEAN UNION, INDIA, PHILIPPINES AND UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1. This document has been submitted by the European Union and United States of America in relation to proposal CoP18 Prop. 28.* Introduction This document has been compiled to supplement the information provided in amendment proposal CoP18 Prop. 28, to include the tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) in Appendix II, as submitted by the European Union, India, Philippines and the United States of America. It highlights a number of key points, responding to the concerns raised within the Secretariat’s assessment of the proposal in CoP18 Doc. 105.1 Annexes 1 and 2: • Despite reports that trade in G. gecko may have decreased from a peak in 2010/2011, overall trade volumes, as well as demand for the species in key consumer countries, appear to remain extremely high. More than 770,000 individuals are exported annually, and combined with undocumented illegal exports, international trade is likely in excess of a million individuals annually. In the absence of population estimates or trends from key exporting countries, such as Thailand and Indonesia, there is a lack of empirical evidence on whether current harvest and trade levels of wild specimens are sustainable. However, population declines that are likely to have been caused by over-collection of individuals have been reported in eight range States. -

The Land of Raptors Monthly Newsletter Monthly

Year 3/Issue 03/November–December 2017 The World After 5 th Extinction Wildlife Corridor Designing for Conservation in India Using Computational Aspects: A Preliminary Interaction Model (Part – I) Asiatic Lion… Human-Lion Interaction in Kathiawar Featuring Asian Biodiversity Asian Featuring Why Tigers become Man Eaters Your God is not Green of Ethereal Bikaner: The Land of Raptors Monthly Newsletter Monthly Cover Photo : Tanmoy Das Year 3/Issue 03/November–December 2017 “The mouse says: I dig a hole without a hoe; the snake says: climb a tree without arms.” ~ Ancient African Hearsay Copper Headed Trinket; Photography by Sauvik Basu Year 3/Issue 03/November–December 2017 The Holocene is the geological epoch that began after the Content : Pleistocene at approximately 11,700 years BP and continues to the present. As Earth warmed after the Ice Age, the human Cover Story population increased and early man began to change the planet Ethereal Bikaner: The Land of forever. For Exploring Nature, our newsletter Holocene is our Raptors by Sandipan Ghosh platform to convey our concerns on human threat to 3|Page biodiversity. We will use our newsletter as a media to highlight the current local and global issues which could impact Editorial biodiversity of Mother Nature and promote awareness of Illegal Wildlife Trade… biodiversity in alignment with our group’s mission of promoting 10|Page awareness of different aspects of Mother Nature among people. Experts’ Voice In this newsletter our readers will get information and periodic Wildlife Corridor Designing for updates on. Conservation in India usin Computational Aspects, A Preliminary Recent significant discussions on biodiversity, going on Interaction Model (Part–I) by Saurabh across the world.