'Dialectic of Marginality': Preliminary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAZILIAN Military Culture

BRAZILIAN Military Culture 2018 Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy | Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center By Luis Bitencourt The FIU-USSOUTHCOM Academic Partnership Military Culture Series Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy (FIU-JGI) and FIU’s Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center (FIU-LACC), in collaboration with the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), formed the FIU-SOUTHCOM Academic Partnership. The partnership entails FIU providing research-based knowledge to further USSOUTHCOM’s understanding of the political, strategic, and cultural dimensions that shape military behavior in Latin America and the Caribbean. This goal is accomplished by employing a military culture approach. This initial phase of military culture consisted of a yearlong research program that focused on developing a standard analytical framework to identify and assess the military culture of three countries. FIU facilitated professional presentations of two countries (Cuba and Venezuela) and conducted field research for one country (Honduras). The overarching purpose of the project is two-fold: to generate a rich and dynamic base of knowledge pertaining to political, social, and strategic factors that influence military behavior; and to contribute to USSOUTHCOM’s Socio-Cultural Analysis (SCD) Program. Utilizing the notion of military culture, USSOUTHCOM has commissioned FIU-JGI to conduct country-studies in order to explain how Latin American militaries will behave in the context -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

A Casa Forte De Rachel De Queiroz

A Casa Forte de Rachel de Queiroz ANA M ARIA R OLAND Resumo Em 1930 teve início um ciclo renovador do modernismo brasileiro e Rachel de Queiroz apresentou-se como a primeira emergente. Na sua obra, a expressão moderna estreita o diálogo entre a literatura e a história, tanto no programa estético, quanto no político. A representação da língua falada, aliada à concisão e ao rigor documental, são virtudes que a escritora cultivou. No seu último romance podemos seguir a atualização da épica moderna na construção de dramas e heróis populares. The Fortress Palavras-chave : Literatura Moderna; Brasil; Representação da Realidade House of Rachel Histórica; Brasil. de Queiroz Abstract In the 1930s, a renewed cycle of Brazilian modernism began, and Rachel de Queiroz was one of its developers. In her work, the modern expression helps the dialogue between literature and history, in both the esthetical and political programs. The representation of the spoken language, associated with conciseness, and documental accuracy, are all virtues that the writer cultivated. In her last romance, we can follow the update of the modern epic in the construction of popular dramas and heroes. ANA M ARIA R OLAND Keywords: Modern Literature; Nationess; Doutora em Sociologia Representation of Historical Reality; Brazil. pela UnB/Faculdade de Ciências Sociais (Flacso), ensaísta e pesquisadora de literatura e cinema. WORLD T ENSIONS | 97 ANA M ARIA R OLAND [...] e me virei para os Serrotes do Pai e do Filho, olhei os dois um instante, depois dei adeus com a mão. Adeus, minha Serra dos Padres! Adeus minha Casa Forte que eu vou levantar! (Raquel de Queiroz, Memorial de Maria Moura). -

Market Access Guide – Brazil 2020 – Table of Contents 01

Market Access Guide – Brazil 2020 – Table of Contents 01. COUNTRY OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................................... 3 02. BRAZILIAN RECORDED MUSIC MARKET .................................................................................................... 5 THE MAJORS .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTERVIEW WITH PAULO JUNQUEIRO, PRESIDENT, SONY MUSIC BRASIL ................................ 10 THE INDEPENDENTS ........................................................................................................................................ 11 CHART SERVICES ................................................................................................................................................. 1 03. POPULAR BRAZILIAN MUSIC - GENRES ...................................................................................................... 1 GOSPEL .................................................................................................................................................................. 16 FUNK ...................................................................................................................................................................... 20 SERTANEJA .......................................................................................................................................................... -

EVANGELHO SEGUNDO RACIONAIS MC's: Ressignificações Religiosas, Políticas E Estético-Musicais Nas Narrativas Do Rap

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO CARLOS CENTRO DE EDUCAÇÃO E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE SOCIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SOCIOLOGIA EVANGELHO SEGUNDO RACIONAIS MC'S: ressignificações religiosas, políticas e estético-musicais nas narrativas do rap SÃO CARLOS 2014 HENRIQUE YAGUI TAKAHASHI EVANGELHO SEGUNDO RACIONAIS MC'S: ressignificações religiosas, políticas e estético-musicais nas narrativas do rap Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em Sociologia do Departamento de Sociologia da Universidade Federal de São Carlos, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Sociologia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Gabriel de Santis Feltran SÃO CARLOS 2014 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pelo DePT da Biblioteca Comunitária da UFSCar Takahashi, Henrique Yagui. T136es Evangelho segundo Racionais MC'S : ressignificações religiosas, políticas e estético-musicais nas narrativas do rap / Henrique Yagui Takahashi. -- São Carlos : UFSCar, 2015. 160 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) -- Universidade Federal de São Carlos, 2014. 1. Música - sociologia. 2. Racionais MC's (Conjunto musical). 3. Rap. 4. Narrativas. 5. Ressignificações. 6. Racialidade. I. Título. CDD: 306.484 (20a) Para minha mãe e minhas irmãs: Mirian, Juliana e Julia. RESUMO: O presente trabalho consiste no estudo de ressignificações nas narrativas do rap do grupo Racionais MC's acerca do cotidiano das periferias urbanas na cidade de São Paulo, durante a virada dos anos de 1990 ao 2000. Essas ressignificações sobre o cotidiano periférico se dariam sob três aspectos: religioso – -

Cinema Nacional E Ensino De Sociologia : Como Trechos De Filme E

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO CURITIBA 2016 ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Educação, no Curso de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Setor de Educação, Linha de Pesquisa Cultura, Escola e Ensino da Universidade Federal do Paraná-UFPR. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Dalla Costa CURITIBA 2016 Dedico este trabalho a todos os profissionais da educação que estiverem na praça Nossa Senhora de Salete (Curitiba) no dia 29 de abril de 2015. RESUMO Estudar o cinema na perspectiva da Sociologia passa, antes de tudo, por uma questão cultural, mas não se limita a isto. Pensar os desdobramentos que cercam a temática do cinema é, também, se deparar com questões de ordem social, política, econômica e ideológica das relações entre indivíduo e sociedade, levando-se em conta que as mesmas são estruturadas a partir das esferas da produção e do consumo. Este conjunto de relações constitui por si mesmo uma problemática das Ciências Sociais. Por isso, quando se trata da sala de aula, a projeção de um filme ou de um trecho de filme, não pode se restringir somente ao lazer ou ao entretenimento. Com a implantação da Lei n° 13.006 de junho de 2014, que torna obrigatória a exibição por 2 horas mensais de filmes nacionais nas escolas, a busca por maneiras de trabalhar o cinema nacional de forma significativa na sala de aula tornou-se premente.Foi a busca pela identificação de diferentes perspectivas de trabalho com cinema nacional no ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica que motivou esta pesquisa. -

LEMINSKIANA, Antología Variada De Paulo Leminski

LEMINSKIANA, Antología variada de Paulo Leminski 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS Este libro ha sido posible gracias al apoyo de las siguientes personas: Alice Ruiz, Toninho Vaz, Fatima María de Oliveira, Italo Moriconi, Roberto Echavarren, Paloma Vidal, Paula Siganevich, Carolina Puente, Germán Conde, Luciana Di Leone, Florencia Garramuño, Gonzalo Aguilar, Claudia Bacci, Amalia Sato, Odile Cisneros, Regis Bonvicino y Solange Rebuzzi. Por otra parte, la Agencia de Promoción Científica nos otorgó un subsidio de investigación que nos permitió en varias ocasiones diferentes viajar a San Pablo para consultar archivos y efectuar entrevistas. 2 Índice -Presentación: Mario Cámara -Poesías O ex-estranho Invernáculo Ya dije de nosotros Desastre de una idea Rimo y reímos Qué se yo Leche, lectura El ruido del serrucho Redonda. No, nunca va a ser redonda. En el momento del todavía Olinda wischral Take p/bere Feliz coincidencia Este planeta, a veces, cansa, Mezcla de tedio y misterio Azules con las sonrisas de los niños Mi yo brasileño Para unas noches que se están haciendo Nunca sé con certeza Tamaño momento A todos los que aman Jeroglífico Hexagrama 65 Dionisios ares afrodite 3 De tertulia poetarum Amar: armas debajo del altar Sacro lavoro Lo que mañana no sabe Dactilografiando este texto Mil y una noches hasta Babel Johnny B. Good Vivir bien Twisted Tongue Por más que yo ande Desperté y me miré en el espejo Arte que te abriga arte que te habita Carne alma S.O.S Re Solo Octubre Vivir es super difícil Sombras Allá van ellas En el centro Después de mucho meditar PARTE DE AM/OR Investígio A una carta pluma Campo de chatarras 1987, ten piedad de nosotros Jardín de mi amiga Ah si por lo menos Amarte a vos es cosa de minutos 4 1. -

Brazilian.Perspectives E.Pdf

edited by Paulo Sotero Daniel Budny BRAZILIAN PERSPECTIVES ON THE UNITED STATES: ADVANCING U.S. STUDIES IN BRAZIL Paulo Sotero editado por Brazil Institute BRAZILIAN PERSPECTIVES ON THE UNITED STATES ADVANCING U.S. STUDIES IN BRAZIL Edited by Paulo Sotero Daniel Budny January 2007 Available from the Latin American Program and Brazil Institute Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org ISBN 1-933549-13-0 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals con- cerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television, and the monthly news-letter “Centerpoint.” For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

Half Title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS in CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN

<half title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS</half title> i Traditions in World Cinema General Editors Linda Badley (Middle Tennessee State University) R. Barton Palmer (Clemson University) Founding Editor Steven Jay Schneider (New York University) Titles in the series include: Traditions in World Cinema Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Jay Schneider (eds) Japanese Horror Cinema Jay McRoy (ed.) New Punk Cinema Nicholas Rombes (ed.) African Filmmaking Roy Armes Palestinian Cinema Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi Czech and Slovak Cinema Peter Hames The New Neapolitan Cinema Alex Marlow-Mann American Smart Cinema Claire Perkins The International Film Musical Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad (eds) Italian Neorealist Cinema Torunn Haaland Magic Realist Cinema in East Central Europe Aga Skrodzka Italian Post-Neorealist Cinema Luca Barattoni Spanish Horror Film Antonio Lázaro-Reboll Post-beur Cinema ii Will Higbee New Taiwanese Cinema in Focus Flannery Wilson International Noir Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer (eds) Films on Ice Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport (eds) Nordic Genre Film Tommy Gustafsson and Pietari Kääpä (eds) Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-Bi Adam Bingham Chinese Martial Arts Cinema (2nd edition) Stephen Teo Slow Cinema Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge Expressionism in Cinema Olaf Brill and Gary D. Rhodes (eds) French Language Road Cinema: Borders,Diasporas, Migration and ‘NewEurope’ Michael Gott Transnational Film Remakes Iain Robert Smith and Constantine Verevis Coming-of-age Cinema in New Zealand Alistair Fox New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas Dolores Tierney www.euppublishing.com/series/tiwc iii <title page>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS Dolores Tierney <EUP title page logo> </title page> iv <imprint page> Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. -

Mario CáMara. Cuerpos Paganos. Usos Y Efectos En La Cultura

Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica Volume 1 Number 75 Article 44 2012 Mario Cámara. Cuerpos paganos. Usos y efectos en la cultura brasileña (1960-1980) Nancy Fernandez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti Citas recomendadas Fernandez, Nancy (April 2012) "Mario Cámara. Cuerpos paganos. Usos y efectos en la cultura brasileña (1960-1980)," Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica: No. 75, Article 44. Available at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti/vol1/iss75/44 This Reseña is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nota sobre Cuerpos paganos (Buenos Aires: Santiago Arcos, 2011), de Mario Cámara. Cuerpos paganos. Usos y efectos en la cultura brasileña (1960-1980) es el libro que Mario Cámara publica en 2011, como producto de su tesis doctoral y de una sostenida investigación a lo largo de los años. Abordando aquellas figuraciones que promueven la emergencia de un imaginario en torno al cuerpo, el texto se abre con un epígrafe de René Descartes sobre su clásica renuncia sensorial, para retornar, ya hacia las últimas páginas, desde el rol protagónico de Catatau (la novela de Paulo Leminski); si el primero enfatiza el intento por depurar la realidad del objeto y la pureza de la razón, el segundo marca la disyuntiva entre el lenguaje del trópico y el consecuente fracaso de clasificar lo real. Las tres décadas señaladas constituyen el objeto de estudio que el autor recorta poniendo énfasis sobre dos problemáticas de índole general. -

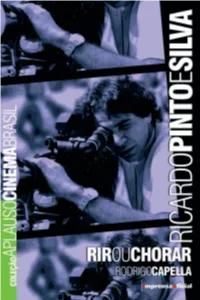

Ricardo Pinto E Silva

Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Ricardo miolo.indd 1 9/10/2007 17:34:34 Ricardo miolo.indd 2 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Rodrigo Capella São Paulo, 2007 Ricardo miolo.indd 3 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Governador José Serra Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Diretor Vice-presidente Paulo Moreira Leite Diretor Industrial Teiji Tomioka Diretor Financeiro Clodoaldo Pelissioni Diretora de Gestão Corporativa Lucia Maria Dal Medico Chefe de Gabinete Vera Lúcia Wey Coleção Aplauso Série Cinema Brasil Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho Coordenador Operacional e Pesquisa Iconográfica Marcelo Pestana Projeto Gráfico Carlos Cirne Editoração Aline Navarro Assistente Operacional Felipe Goulart Tratamento de Imagens José Carlos da Silva Revisão Amancio do Vale Dante Pascoal Corradini Sarvio Nogueira Holanda Ricardo miolo.indd 4 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Apresentação “O que lembro, tenho.” Guimarães Rosa A Coleção Aplauso, concebida pela Imprensa Oficial, tem como atributo principal reabilitar e resgatar a memória da cultura nacional, biogra- fando atores, atrizes e diretores que compõem a cena brasileira nas áreas do cinema, do teatro e da televisão. Essa importante historiografia cênica e audio- visual brasileiras vem sendo reconstituída de manei ra singular. O coordenador de nossa cole- ção, o crítico Rubens Ewald Filho, selecionou, criteriosamente, um conjunto de jornalistas especializados para rea lizar esse trabalho de apro ximação junto a nossos biografados. Em entre vistas e encontros sucessivos foi-se estrei- tan do o contato com todos. Preciosos arquivos de documentos e imagens foram aber tos e, na maioria dos casos, deu-se a conhecer o universo que compõe seus cotidianos.