Land of Sikyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UK APPG on Population, Development and Reproductive Health Study Tour to Athens, Greece 3Rd- 4Th December 2016

UK APPG on Population, Development and Reproductive Health study tour to Athens, Greece 3rd- 4th December 2016 Greece study tour delegation: Baroness Northover, Baroness Tonge, Baroness Jenkin, Baroness Hodgson, Lord Purvis, Baroness Uddin and Baroness Barker, Acropolis, Athens, Greece Executive Summary The UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Population, Development and Reproductive Health (APPG on PDRH) organised a study tour to Athens, Greece 3rd- 4th December 2016, with a cross party UK parliament delegation. The delegation included: Baroness Jenny Tonge, Baroness Jenkin, Baroness Barker, Baroness Uddin, Baroness Northover, Baroness Hodgson and Lord Purvis. The study tour was co-hosted by UNFPA with support from Merck & Co (MSD) Greece. The aim of the study tour was to strengthen UK Parliamentarians knowledge of family planning (FP), sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) service provisions in refugee settings and enhance the membership of the UK APPG on PDRH. UK delegation at the Migrant and Refugee Accommodation facility (refugee camp) in Oenofyta The UK delegation visited the Migrant and Refugee Accommodation facility (refugee camp) at the old Hellenic air-force base on the outskirt of Athens Saturday morning. At the camp, delegates noted the living conditions, met and spoke to refugees whom were mainly from Afghanistan and were briefed by the Doctors of the World Greece (MDM) staff on health service provisions in the camp. In the afternoon delegates were briefed and met with a large group of organisations working and supporting refugees in camps in Greece. UK delegation NGO briefing, Hydra Restaurant, Athens Saturday evening the delegation visited Victoria Square in the center of Athens, where many refugees congregate. -

Bischofswerda the Town and Its People Contents

Bischofswerda The town and its people Contents 0.1 Bischofswerda ............................................. 1 0.1.1 Geography .......................................... 1 0.1.2 History ............................................ 1 0.1.3 Sights ............................................. 2 0.1.4 Economy and traffic ...................................... 2 0.1.5 Culture and sports ....................................... 3 0.1.6 Partnership .......................................... 3 0.1.7 Personality .......................................... 3 0.1.8 Notes ............................................. 4 0.1.9 External links ......................................... 4 0.2 Großdrebnitz ............................................. 4 0.2.1 History ............................................ 4 0.2.2 People ............................................ 5 0.2.3 Literature ........................................... 6 0.2.4 Footnotes ........................................... 6 0.3 Wesenitz ................................................ 6 0.3.1 Geography .......................................... 6 0.3.2 Touristic Attractions ..................................... 6 0.3.3 Historical Usage ....................................... 7 0.3.4 Fauna ............................................. 7 0.3.5 References .......................................... 7 1 People born in or working for Bischofswerda 8 1.1 Abd-ru-shin .............................................. 8 1.1.1 Life, Publishing, Legacy ................................... 8 1.1.2 Legacy -

Verification of Vulnerable Zones Identified Under the Nitrate Directive \ and Sensitive Areas Identified Under the Urban Waste W

CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 THE URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT DIRECTIVE (91/271/EEC) 1 1.2 THE NITRATES DIRECTIVE (91/676/EEC) 3 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 4 2 THE OFFICIAL GREEK DESIGNATION PROCESS 9 2.1 OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT SITUATION IN GREECE 9 2.2 OFFICIAL DESIGNATION OF SENSITIVE AREAS 10 2.3 OFFICIAL DESIGNATION OF VULNERABLE ZONES 14 1 INTRODUCTION This report is a review of the areas designated as Sensitive Areas in conformity with the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive 91/271/EEC and Vulnerable Zones in conformity with the Nitrates Directive 91/676/EEC in Greece. The review also includes suggestions for further areas that should be designated within the scope of these two Directives. Although the two Directives have different objectives, the areas designated as sensitive or vulnerable are reviewed simultaneously because of the similarities in the designation process. The investigations will focus upon: • Checking that those waters that should be identified according to either Directive have been; • in the case of the Nitrates Directive, assessing whether vulnerable zones have been designated correctly and comprehensively. The identification of vulnerable zones and sensitive areas in relation to the Nitrates Directive and Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive is carried out according to both common and specific criteria, as these are specified in the two Directives. 1.1 THE URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT DIRECTIVE (91/271/EEC) The Directive concerns the collection, treatment and discharge of urban wastewater as well as biodegradable wastewater from certain industrial sectors. The designation of sensitive areas is required by the Directive since, depending on the sensitivity of the receptor, treatment of a different level is necessary prior to discharge. -

Samenvatting Summary

SAMENVATTING SUMMARY 1. H. G. BEYEN: THE SOCIAL STATUS OF THE PAINTER IN GREEK ANTIQUITY The opinion has been expressed on more than one occasion that in the Greek world the sculptor or painter was not held in esteem as much as one would have expected, because. people invariably saw the f3avav(Jo~ , i.e, the artisan in him. This opinion is founded mainly on passages in Plato and Aristotle. However, the word f3avav(Jo~ was tinged with an element of contempt only to the conser- vative aristocrat and to the abstract thinker who saw an unbridgeable gulf between the work of the mind and that done by hand. Plato combined the two types and even Aristotle's liberality was extremely moderate. They definitely do not voice the "communis opinio". Polygnotus was a national character and was thought ofvery highly. Owing to his distinguished, human art [mural decoration in the full sense ofthe word, destined for the community] he became the educator of his contemporaries. He was honoured by numerous distinctions [such as the citizenship ofAthens, "hospitia gratuita" on behalf ofthe Delphic Amphictyom, the appointment as {}ewe6~ by his native town Thasos]. The subsequent period (from about 45o-about 325) was the time when indi- vidualism and the "free" art of painting, i.e. not executed in connection with architecture and carried out in the studio on panels or slabs ofmarble, flourished. In this period too the painters reaped great personal fame and considerable riches [Zeuxis, Nicias], presumably even more so than the sculptors. The self-assurance of some of them is reminiscent of that of the artists of the Renaissance [Parrha- sius]. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Faunal Remains

This is a repository copy of Faunal remains. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/169068/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Halstead, P. orcid.org/0000-0002-3347-0637 (2020) Faunal remains. In: Wright, J.C. and Dabney, M.K., (eds.) The Mycenaean Settlement on Tsoungiza Hill. Nemea Valley Archaeological Project (III). American School of Classical Studies at Athens , Princeton, New Jersey , pp. 1077-1158. ISBN 9780876619247 Copyright © 2020 American School of Classical Studies at Athens, originally published in The Mycenaean Settlement on Tsoungiza Hill (Nemea Valley Archaeological Project III), by James C. Wright and Mary K. Dabney. This offprint is supplied for personal, noncommercial use only. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Copyright © 2020 American School of Classical Studies at Athens, originally published in The Mycenaean Settlement on Tsoungiza Hill (Nemea Valley Archaeological Project III), by James C. -

Delineation of Recharge Areas of the Aquifer Systems of Corinthia Prefecture by the Use of Isotopic Evidence

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece Vol. 47, 2013 Delineation of recharge areas of the aquifer systems of Corinthia prefecture by the use of isotopic evidence Antonakos A. General Secretariat for Civil Protection Nikas K. IGME http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11102 Copyright © 2017 A. Antonakos, K. Nikas To cite this article: Antonakos, A., & Nikas, K. (2013). Delineation of recharge areas of the aquifer systems of Corinthia prefecture by the use of isotopic evidence. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 47(2), 692-701. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11102 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 02/08/2019 18:32:42 | Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, vol. XLVII 2013 Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, τομ. XLVII , 2013 Proceedings of the 13th International Congress, Chania, Sept. Πρακτικά 13ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Χανιά, Σεπτ. 2013 2013 DELINEATION OF RECHARGE AREAS OF THE AQUIFER SYSTEMS OF CORINTHIA PREFECTURE BY THE USE OF ISOTOPIC EVIDENCE Antonakos A.1 and Nikas K.2 1 General Secretariat for Civil Protection, Evagelistrias 2, 105 63, Athens, [email protected] 2 IGME. 1st Spirou Louis St., Olympic Village, 13677 Acharnae. [email protected] Abstract The results of a ground water isotopic research program conducted during the peri- od 2004-2008 by an IGME/Hydrogeology Department team in the area of North Ko- rinthian prefecture are presented here. 69 ground water samples were collected dur- ing the period 6/2007 and analyzed in the laboratory of Isotope Hydrology of NCSR "Demokritos" for Oxygen isotopes δ18O and Tritium. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Report on Territorial Diagnosis

CREADIS3: REPORT ON TERRITORIAL DIAGNOSIS. WESTERN GREECE Regional Development Fund on behalf of Region of Western Greece June 2018 2 INDEX 1. General Introduction ........................................................................................................... 3 1.1. The Project .......................................................................................................................3 1.2. The Region of Western Greece and the Project ........................................................4 2. Regional contexts ................................................................................................................ 5 2.1. Territory`s General Profile ..............................................................................................5 2.2. Territory`s CCI Profile ....................................................................................................8 3. CCI Sector Analysis: Evolution and Current Situation ................................................12 3.1. Evolution .........................................................................................................................12 3.2. Current Situation...........................................................................................................14 3.3. Creative Districs ............................................................................................................15 4. CCI Sector characterization .............................................................................................17 4.1. Stakeholders -

KARYES Lakonia

KARYES Lakonia The Caryatides Monument full of snow News Bulletin Number 20 Spring 2019 KARYATES ASSOCIATION: THE ANNUAL “PITA” DANCE THE BULLETIN’S SPECIAL FEATURES The 2019 Association’s Annual Dance was successfully organized. One more time many compartiots not only from Athens, but also from other CONTINUE cities and towns of Greece gathered together. On Sunday February 10th Karyates enjoyed a tasteful meal and danced at the “CAPETANIOS” hall. Following the positive response that our The Sparta mayor mr Evagellos first special publication of the history of Valliotis was also present and Education in Karyes had in our previous he addressed to the Karyates issue, this issue continues the series of congratulating the Association tributes to the history of our country. for its efforts. On the occasion of the Greek National After that, the president of the Independence Day on March 25th, we Association mr Michael publish a new tribute to the Repoulis welcome all the participation of Arachovitians/Karyates compatriots and present a brief in the struggle of the Greek Nation to report for the year 2018 and win its freedom from the Ottoman the new year’s action plan. slavery. The board members of the Karyates Association Mr. Valliotis, Sparta Mayor At the same time, with the help of Mr. The Vice President of the Association Ms Annita Gleka-Prekezes presented her new book “20th Century Stories, Traditions, Narratives from the Theodoros Mentis, we publish a second villages of Northern Lacedaemon” mentioning that all the revenues from its sells will contribute for the Association’s actions. special reference to the Karyes Dance Group. -

Greece | Forest Fires in Peloponnese and Rhodes and EU Response

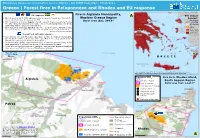

Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) – DG ECHO Daily Map | 04/08/2021 Greece | Forest fires in Peloponnese and Rhodes and EU response Fire in Aigialeia Municipality, EU response A Fire danger ▪ On 3 August at 18:30 UTC, Greece made a request of assistance through the Western Greece Region forecast1 Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM). Burnt area (ha): 394.9* 3-9 August ▪ On 4 August at 3:31 UTC, Cyprus offered 1 ground forest fire fighting module Source: JRC-EFFIS (40 pax) and 2 air tractors with 8 pax. The offer was accepted by the Greek Moderate authorities and the deployment is ongoing. ▪ On 4 August at 8:48 UTC, Sweden offered 1 aerial forest fire fighting module High A (2 fireboss via the rescEU). The offer was accepted by the Greek authorities. Very high Source: DG ECHO, as of 4 August Extreme Impact and national response ▪ According to the Civil Protection Operation Center, in Aigialeia Municipality, Aegean 230 firefighters with 116 vehicles were operating in the area, assisted by 5 Sea ground force groups, 8 helicopters and 8 planes. ▪ In Rhodes Municipality, 159 firefighters with 34 vehicles were operating in the area, assisted by 6 ground force group, 6 helicopters and 3 planes. ▪ There are no reported injuries or fatalities, and although damaged buildings have been reported there are no official figures available Source: Greek Civil Protection, as of 3 August at 18:36 UTC Approximately Gulf of Corinth 10 km to Patras B GREECE Sea of Crete MEDITERRANEAN SEA 1The maximum value of the fire danger forecast module of EFFIS, which generates daily maps of forecasted fire danger level using numerical weather predictions. -

Archaeology, Hydrogeology and Geomythology in the Stymphalos Valley

This is a repository copy of Archaeology, Hydrogeology and Geomythology in the Stymphalos Valley. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/116010/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Walsh, Kevin James orcid.org/0000-0003-1621-2625, Brown, A.G., Gourley, Robert Benjamin et al. (1 more author) (2017) Archaeology, Hydrogeology and Geomythology in the Stymphalos Valley. Journal of Archaeological Science Reports. ISSN 2352-409X https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.03.058 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: JASREP-D-16-00231R1 Title: Archaeology, Hydrogeology and Geomythology in the Stymphalos Valley Article Type: SI: Human-Env interfaces Keywords: Mediterranean palaeoenvironment, greece, Geoarchaeology, Hydrogeology, mythology, Greek & Roman Archaeology Corresponding Author: Dr Kevin James Walsh, Dr Corresponding Author's Institution: University of York First Author: Kevin James Walsh, Dr Order of Authors: Kevin James Walsh, Dr; Anthony G Brown, PhD; Rob Scaife, PhD; Ben Gourley, MA Abstract: This paper uses the results of recent excavations of the city of Stymphalos and environmental studies on the floor of the Stymphalos polje to examine the role of both the lake and springs in the history of the classical city.