IAN TALBOT the 1947 Partition of India and Migration: a Comparative Study of Punjab and Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Any Person May Make a Complaint About The

HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (C) No. 4944 of 2009 PETITIONER : Rajendra Singh (Arora). V E R S U S RESPONDENTS : State of Chhattisgarh & Others. PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 226/227 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA SB: Hon’ble Shri Satish K. Agnihotri, J. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Present: Shri Kishore Shrivastava, Senior Advocate with Shri Sanjay Tamrakar, Shri Ashish Shirvastava and Shri Anshuman Shrivastava, Advocates for the petitioner. Shri V.V.S.Moorthy, Deputy Advocate General for the State/ respondent No. 1, 2, 4 and 5. Dr. N.K.Shukla, Senior Advocate with Shri Aditya Khare, Advocates for the respondent No. 7 and 8. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- O R D E R (Delivered on 10th day of July, 2013) 1. The petitioner mainly challenges the order dated 23.07.2007 (Annexure P/14) passed by the High Power State Level Caste Scrutiny Committee i.e. respondent No. 3 (for short ‘the Committee’) wherein the petitioner has been found that he does not belong to “Lohar” i.e. Other Backward Class category, and also the subsequent order dated 28.08.2009 (Annexure P/2) wherein on the basis of the order dated 22.09.2008 (Annexure P/1) the petitioner was disqualified for a further period of five years in view of the provisions of section 19(2) of the Chhattisgarh Municipal Corporation Act, 1956 (for short 'the Act, 1956'). 2. The facts, in brief, are that the petitioner, in the year 2000, contested the election as Councillor from Ward No. 22, Municipal 2 Corporation, Bhilai, declaring himself as a member of “Lohar” community that comes within OBC category on the basis of social status certificate dated 10.04.2000 (Annexure P/3). -

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders Nation The word “NATION” is derived from Latin route “NATUS” of “NATIO” which means “Birth” of “Born”. Therefore, Nation implies homogeneous population of the people who are organized and blood-related. Today the word NATION is used in a wider sense. A Nation is a body of people who see part at least of their identity in terms of a single communal identity with some considerable historical continuity of union, with major elements of common culture, and with a sense of geographical location at least for a good part of those who make up the nation. We can define nation as a people who have some common attributes of race, language, religion or culture and united and organized by the state and by common sentiments and aspiration. A nation becomes so only when it has a spirit or feeling of nationality. A nation is a culturally homogeneous social group, and a politically free unit of the people, fully conscious of its psychic life and expression in a tenacious way. Nationality Mazzini said: “Every people has its special mission and that mission constitutes its nationality”. Nation and Nationality differ in their meaning although they were used interchangeably. A nation is a people having a sense of oneness among them and who are politically independent. In the case of nationality it implies a psychological feeling of unity among a people, but also sense of oneness among them. The sense of unity might be an account, of the people having common history and culture. -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Urdu Language

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2021 (9) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER URDU LANGUAGE Dr. Sohaib Mukhtar Bahria University, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract Urdu is the national language of Pakistan under article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. Urdu language is the first brick upon which whole building of Pakistan is built. In pronunciation both Hindi in India and Urdu in Pakistan are same but in script Indian choose their religious writing style Sanskrit also called Devanagari as Muslims of Pakistan choose Arabic script for writing Urdu language. Urdu language is based on two nation theory which is the basis of the creation of Pakistan. There are two nations in Indian Sub-continent (i) Hindu, and (ii) Muslims therefore Muslims of Indian sub- continent chanted for separate Muslim Land Pakistan in Indian sub-continent thus struggled for achieving separate homeland Pakistan where Muslims can freely practice their religious duties which is not possible in a country where non-Muslims are in majority thus Urdu which is derived from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish declared the national language of Pakistan as official language is still English thus steps are required to be taken at Government level to make Urdu as official language of Pakistan. There are various local languages of Pakistan mainly: Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Kashmiri, Balti and it is fundamental right of all citizens of Pakistan under article 28 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973 to protect, preserve, and promote their local languages and local culture but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu according to article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

Population Genetics for Autosomal STR Loci in Sikh Population Of

tics: Cu ne rr e en G t y R r e a t s i e d a e r r c e h Dogra, et al., Hereditary Genet 2015, 4:1 H Hereditary Genetics ISSN: 2161-1041 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1041.1000142 Research Article Open Access Population Genetics for Autosomal STR Loci in Sikh Population of Central India Dogra D1, Shrivastava P2*, Chaudhary R3, Gupta U2 and Jain T2 1Department of Biotechnology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal 462023, Madhya Pradesh, India 2DNA Fingerprinting Unit, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar 470001, Madhya Pradesh, India 3Biotechnology Division, Department of Zoology, Government Motilal Vigyan Mahavidyalaya, Bhopal 462023, Madhya Pradesh, India *Corresponding author: Pankaj Shrivastava, DNA Fingerprinting Unit, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar-470001, Madhya Pradesh, India, Tel: 94243 71946, E- mail: [email protected] Rec date: February 4, 2015, Acc date: February 23, 2015, Pub date: February 26, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Dogra D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract This study is an attempt to generate genetic database for three endogamous populations of Sikh population (Arora, Jat and Ramgariha) of Central India. The analysis of eight autosomal STR loci (D16S539, D7S820, D13S317, FGA, CSF1PO, D21S11, D18S51, and D2S1338) was done in 140 unrelated Sikh individuals. In all the three studied populations, all loci were in Hardy -Weinberg equilibrium except at locus FGA in Ramgariha Sikh and locus D16S539 in Arora Sikh. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

Reflections on the Transfer of Power and Jawaharlal Nehru Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mountbatten of Burma KG PC GCB OM GCSI GCIE GCVO DSO FRS

Reflections on the Transfer of Power and Jawaharlal Nehru Admiral of the Fleet The Earl Mountbatten of Burma KG PC GCB OM GCSI GCIE GCVO DSO FRS Trinity College, University of Cambridge - 14th November 1968. This is the second Nehru Memorial Lecture. At the suggestion of the former President of India the first was given, most appropriately, by the Master of Jawaharlal Nehru’s old College, Trinity. Lord Butler was born in India, the son of a most distinguished member of the Indian Civil Service, who was one of the most successful Governors. As Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for India he was one of those responsible for the truly remarkable 1935 Government of India Act, the Act which I used to speed up the transfer of power. Thus Lord Butler’ ties with India are strong and it not surprising that he gave such an excellent lecture, which has set such a high standard. He dealt faithfully with the life and career of Jawaharlal Nehru from his birth seventy-nine years ago this very day up to 1947. My fellow trustees of the Nehru Memorial Trust have persuaded me to deliver the second lecture. This seemed the occasion to give a connected narrative of the events leading up to the transfer of power in August 1947, and indeed to continue up to June 1948, when I ceased to be India’s first Constitutional Governor-General. It would have been nice to show how Nehru fitted into these events, but in the time available such a task soon proved to be out of the question, so I have deliberately confined myself to recalling the highlights of my Viceroyalty and to assessing Nehru’s relations to the principal men and events at the time, and to general reminiscences of him to illustrate the part he played up to the actual transfer of power. -

University Archives Inventory

University Archives Inventory Record Group Number: UR001.03 Title: Burney Lynch Parkinson Presidential Records Date: 1926-1969 Bulk Date: 1932-1952 Extent: 42 boxes Creator: Burney Lynch Parkinson Administrative/Biographical Notes: Burney Lynch Parkinson (1887-1972) was an educator from Lincoln, Tennessee. He received his B.S. from Erskine College in 1909, and rose up the administrative ranks from English teacher in Laurens, South Carolina public schools. He received his M.A. from Peabody College in 1920, and Ph.D. from Peabody in 1926, after which he became president of Presbyterian College in Clinton, SC in 1927. He was employed as Director of Teacher Training, Certification, and Elementary Education at the Alabama Dept. of Education just before coming to MSCW to become president in 1932. In December 1932, the university was re-accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, ending the crisis brought on the purge of faculty under Governor Theodore Bilbo, but appropriations to the university were cut by 54 percent, and faculty and staff were reduced by 33 percent, as enrollment had declined from 1410 in 1929 to 804 in 1932. Parkinson authorized a study of MSCW by Peabody college, ultimately pursuing its recommendations to focus on liberal arts at the cost of its traditional role in industrial, vocational, and technical education. Building projects were kept to a minimum during the Parkinson years. Old Main was restored and named for Mary Calloway in 1938. Franklin Hall was converted to a dorm, and the Whitfield Gymnasium into a student center with the Golden Goose Tearoom inside. Parkinson Hall was constructed in 1951 and named for Dr. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Index More Information

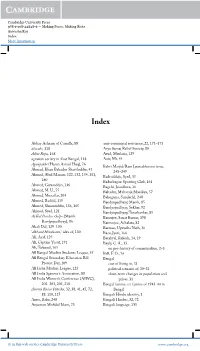

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information Index 271 Index Abhay Ashram of Comilla, 88 anti-communal resistance, 22, 171–175 abwabs, 118 Arya Samaj Relief Society, 80 Adim Ripu, 168 Azad, Maulana, 129 agrarian society in East Bengal, 118 Aziz, Mr, 44 Agunpakhi (Hasan Azizul Huq), 76 Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi issue, Ahmad, Khan Bahadur Sharifuddin, 41 248–249 Ahmed, Abul Mansur, 122, 132, 134, 151, Badrudduja, Syed, 35 160 Badurbagan Sporting Club, 161 Ahmed, Giyasuddin, 136 Bagchi, Jasodhara, 16 Ahmed, M. U., 75 Bahadur, Maharaja Manikya, 57 Ahmed, Muzaffar, 204 Bahuguna, Sunderlal, 240 Ahmed, Rashid, 119 Bandyopadhyay, Manik, 85 Ahmed, Shamsuddin, 136, 165 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, 92 Ahmed, Syed, 121 Bandyopadhyay, Tarashankar, 85 Aj Kal Porshur Golpo (Manik Banerjee, Sanat Kumar, 198 Bandyopadhyay), 86 Bannerjee, Ashalata, 82 Akali Dal, 129–130 Barman, Upendra Nath, 36 ‘Akhand Hindustan,’ idea of, 130 Basu, Jyoti, 166 Ali, Asaf, 129 Batabyal, Rakesh, 14, 19 Ali, Captain Yusuf, 191 Bayly, C. A., 13 Ali, Tafazzal, 165 on pre-history of communalism, 2–3 All Bengal Muslim Students League, 55 Bell, F. O., 76 All Bengal Secondary Education Bill Bengal Protest Day, 109 cost of living in, 31 All India Muslim League, 123 political scenario of, 30–31 All India Spinner’s Association, 88 short-term changes in population and All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), prices, 31 202–203, 205, 218 Bengal famine. see famine of 1943-44 in Amrita Bazar Patrika, 32, 38, 41, 45, 72, Bengal 88, 110, 115 Bengali Hindu identity, 1 Amte, Baba, 240 Bengali Hindus, 32, 72 Anjuman Mofidul Islam, 73 Bengali language, 135 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information 272 Index The Bengali Merchants Association, 56 C. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play.