The Sense and Sensation of Body Modification Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right Arm Resource Update

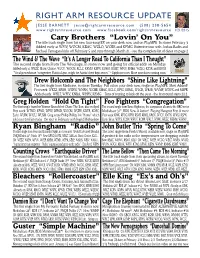

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 1/21/2015 Cary Brothers “Lovin’ On You” The title track single from his new four-song EP, on your desk now and on PlayMPE In stores February 3 Added early at WFIV, WOCM, KBAC, WZLO, WCBE and KFMG Extensive tour with Joshua Radin and Rachael Yamagata kicks off February 5 and runs through March 21 - see the complete list of dates on page 2 The Wind & The Wave “It’s A Longer Road To California Than I Thought” The second single from From The Wreckage, in stores now and going for official adds on Monday Added early at WEZZ, Music Choice, WJCU, WOCM, KCLC, KFMU, KSPN, KOHO, KSMT, WFIV, KNBA, WZLO, KZYR and KRVM “Vocal powerhouse / songwriter, Patricia Lynn, might be Austin’s best-kept secret.” – Epiphone.com More tour dates coming soon Drew Holcomb and The Neighbors “Shine Like Lightning” The first single from Medicine, in stores Tuesday Full cd on your desk now, single on PlayMPE Most Added! First week: WEZZ, KRSH, WZEW, WNRN, WCBE, KBAC, KCLC, KPIG, KRML, WLCE, WBJB, WVMP, WDVX and MSPR Added early: WRLT, WFIV, KNBA, WHRV, KFMG Tons of touring to kick off the year - the first round starts 2/12 Greg Holden “Hold On Tight” Foo Fighters “Congregation” The first single from his Warner Bros debut Chase The Sun, due in April The second single from Sonic Highways, the companion album to the HBO series First week: WTMD, KPND, WFIV, WBSD, WOCM, WCBE, KDTR, KDEC Mediabase 31*, BDS New & Active! Playing Hangout Fest & more Early: WUIN, WJCU, WUSM Greg wrote Phillip Phillips’ hit “Home” which First week: KINK, KFOG, KPRI, KSMT, KRML, KROK, WJCU, KMTN, KFMU, KSPN.. -

UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCSF UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Healing Marks: Body modification in coping with trauma, identity, and its ramifications for stigma and social capital Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vc6j77m Author Keagy, Carolyn D. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Healing Marks: Body modification in coping with trauma, identity, and its ramifications for stigma and social capital by Carolyn Diane Keagy DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Sociology in the GRADUATE DryISION ofthe UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO Copyright 2015 by Carolyn Diane Keagy ii Dedication and acknowledgements This work is dedicated to the members of my sample. These were friends, friends of friends, and strangers that went out of their way to generously donate their time to this project for no perceivable compensation. For many this meant trusting me with the most sensitive stories of their lives, and for that reason this work is ultimately for them. This is not to ignore the immeasurable support from my family, advisor, committee members, employer, and multiple counter culture communities that support me. This project would not have been completed without that support and is truly invaluable. iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to expand the knowledge base on the experience of living as an individual who engages in body modification. Body modification is the intentional and voluntary alteration of the body for non-medically necessary reasons and not meant to intentionally “harm” oneself. The study seeks to understand how individuals negotiate the personal, emotional, and social experience of engaging in body modification. -

Kang Sung R.Pdf

ILLUSTRATED AMERICA: FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF TATTOOS IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 2014 By Sung P. Kang Dissertation Committee: Herbert Ziegler, Chairperson Margot Henriksen Marcus Daniel Njoroge Njoroge Kathryn Hoffmann Keywords: tattoos, skin art, sports, cultural studies, ethnic studies, gender studies ©Copyright 2014 by Sung P. Kang ii Acknowledgements This dissertation would not be possible without the support and assistance of many of the History Department faculty and staff from the University of Hawaii, colleagues from Hawaii Pacific University, friends, and family. I am very thankful to Njoroge Njoroge in supplying constant debates on American sports and issues facing black athletes, and furthering my understanding of Marxism and black America. To Kathryn Hoffmann, who was a continuous “springboard” for many of my theories and issues surrounding the body. I also want to thank Marcus Daniel, who constantly challenged my perspective on the relationship between politics and race. To Herbert Ziegler who was instrumental to the entire doctoral process despite his own ailments. Without him none of this would have been possible. To Margot (Mimi) Henriksen, my chairperson, who despite her own difficulties gave me continual assistance, guidance, and friendship that sustained me to this stage in my academic career. Her confidence in me was integral, as it fed my determination not to disappoint her. To my chiropractor, Dr. Eric Shimane, who made me physically functional so I could continue with the grueling doctoral process. -

Part 1 Extreme Tattooing

01-Goode-45291.qxd 7/2/2007 3:22 PM Page 1 PART 1 EXTREME TATTOOING 1 01-Goode-45291.qxd 7/2/2007 3:22 PM Page 2 BOD MOD TO THE MAX! An Introduction to Body Modification as Deviance s we saw in the Introduction,deviance is a matter of definition.People make sense of the Abehavior, beliefs, and physical characteristics of others in a variety of ways so that those behaviors, beliefs, and characteristics become social objects; in other words, they are socially constructed.Which kinds of social objects they become, and to whom, will depend to a large extent on social context: In what contexts do these behaviors take place, how are these beliefs expressed, and who possesses these traits or characteristics? Along similar lines, other kinds of social objects—people’s hairdos, their clothes, the makeup they choose to wear, the size of their feet—are all bodily objects, but they become what they are to us through the same process of social definition. Thus, people learn to see heavy eye liner, skinny neckties, beehive hairdos, and polyester leisure suits as appropriate, attractive, silly, fun—or grotesquely outdated—and/or vintage aspects of the ways people can present themselves. In fact, most of us spend a considerable amount of time in any given week changing the ways we look.We might wear a t-shirt or a sweatshirt bearing our favorite team’s logo after a win but choose not to after a loss. We rarely wear the same out- fit when we go to a job interview as we do when lounging around the living room, watching television. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 7/16/2014 J Mascis “Every Morning” The first single from Tied To A Star, going for adds on Monday, available in stores August 26 Added early at WFUV, SiriusXM Loft, WERS, KSMT, KDEC and WHRV Available on PlayMPE Produced by Mascis, the album features guest appearances from Cat Power’s Chan Marshall, Black Heart Procession’s Pall Jenkins, Mark Mulcahy and Ken Maiuri from Young@Heart Chorus Named one of Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Guitarists Extensive tour begins in September - see page 3 Kings of Leon “Family Tree” The fourth single from Mechanical Bull New: WVOD, KBAC, WAPS Already on: WRLT, WFPK, KUTX, KCSN, KPND, WYMS, KSMT, WLCE, WUIN, WFIV, WMWV, KMMS, KROK, KNBA and more Performing on GMA on July 25 Headlining tour this summer: 7/31 St. Louis, 8/1 Detroit, 8/3 Chicago (headlining Lollapalooza), 8/7 Hartford, 8/9 Boston, 8/10 Saratoga Springs, 8/13 Wantagh NY, 8/15 Bristow VA, 8/16 Bethel NY, 8/19 Darien NY, 8/20 Cleveland, 8/22 Cincinnati, 8/23 Indianapolis and more through 10/5 The Mastersons “Good Luck Charm” Full cd Good Luck Charm in stores and on your desk now New: KPIG, KSMF Already on: WNKU, WCBE, WEXT, KDHX, WNCW, WYCE, WBJB, WFHB,WUMB, KSUT, WFIV, WOCM, MSPR, WDVX, KDNK, KVNF... “They are poised to be one of Austin’s breakout acts of 2014” - Austin American Statesman All of the songs were co-written by Chris and Eleanor, giving the material added depth as well as a power- ful collective lyrical identity that’s matched by their expressive harmonies. -

Alone Among Friends and How Memories of the Father Inform a Son's Understanding of Masculinity in the Novels of Per Petterson

1 Alone Among Friends and How Memories of the Father Inform a Son's Understanding of Masculinity in the Novels of Per Petterson Submitted by Adam Gallari to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English In August 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract A combination of an original work of fiction, Alone Among Friends, and a critical discussion of masculinity in the work of Per Petterson, this dissertation joins a growing conversation in the field of Masculine Studies about the depiction of men in literature. Written in a spare and realistic style, Alone Among Friends is a novella that hopes to explore ideas of masculinity, friendship, success, and failure present in the mindset of the American Millennial generation. Takings its cues from The Sun Also Rises, Light Years, and The Salt Point, Alone Among Friends examines the destructive nature of hyper-masculinity and highlights the danger of attaching too much meaning to external validation as the measuring stick for one's self worth. Moreover, Alone Among Friends is also influenced by the themes of memory and knowing found within the work of Per Petterson. "How Memories of the Father Inform a Son's Understanding of Masculinity in the Novels of Per Petterson" discusses the ways in which Per Petterson, a Norwegian writer, has been both influenced by American notions of masculinity and also managed to incorporate European aspects of family into his work to create a unique hybrid perspective that merges the American idea of the emancipated male protagonist with the European family centered narrative. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Bleachers, Us the Duo and Bea Miller Join Pitbull & All

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACTS: Caroline Galloway M2M PR [email protected] BLEACHERS, US THE DUO AND BEA MILLER JOIN PITBULL & ALL-STAR LINEUP dd͘:͘DZd>>&KhEd/KE͛^ 15TH ANNUAL FAMILY DAY HONORING ZZKZ^͛dKDKZ^KEE&D/>z Bleachers, Us The Duo and Bea Miller to perform along with Pitbull and Timeflies at Family Day Event hosted by Hilary Duff on September 28, 2014 in NYC New York, NY ʹ (September 9, 2014) ʹ The T.J. Martell Foundation is proud to announce the addition of Bleachers, Us The Duo and Bea Miller to their impressive lineup of performers for its 15th Annual Family Day on Sunday, September 28, 2014 at Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City. Grammy award-winning musician, Jack Antonoff (Steel Train, Fun.), who released the debut album for his newest musical endeavor Bleachers on RCA Records is excited to be a part of Family Day ʹ ͞/͛ŵŚŽŶŽƌĞĚƚŽďĞƉĞƌĨŽƌŵŝŶŐĂƚ&ĂŵŝůLJĂLJ this year honoring Tom Corson. Tom, along with my entire RCA Records family, has been incredibly supportive of me and of Bleachers and I am thrilled to be able to be there to support him and such a good ĐĂƵƐĞ͘͟ ůĞĂĐŚĞƌƐ͛ĚĞďƵƚĂůďƵŵ͕ĞŶƚŝƚůĞĚ͞^ƚƌĂŶŐĞĞƐŝƌĞ͕͟ has been critically acclaimed since day one with ƚŚĞĨŝƌƐƚƐŝŶŐůĞ͞/tĂŶŶĂ'ĞƚĞƚƚĞƌ͟ƋƵŝĐŬůLJƌŝƐŝŶŐƚŽηϭŽŶƚŚĞĂůƚernative radio chart. Michael and Carissa Alvarado of Us the Duo ĂƌĞĂŶŽƚŚĞƌǁĞůĐŽŵĞĂĚĚŝƚŝŽŶƚŽƚŚŝƐLJĞĂƌ͛Ɛ&ĂŵŝůLJĂLJƌŽƐƚĞƌ͘ This husband and wife team have gained ƋƵŝĐŬĞdžƉŽƐƵƌĞǁŝƚŚƚŚĞŝƌƐĞĐŽŶĚĂůďƵŵ͕͞EŽDĂƚƚĞƌtŚĞƌĞzŽƵ ƌĞ͕͟ǁŚŝĐŚŚĂƐƌĂĐĞĚƚŽηϵŽŶƚŚĞŝdƵŶĞƐƉŽƉĐŚĂƌƚƐŝŶĐĞŝƚƐƌĞ-release via Republic Records. The social media-savvy duo have also made a name for themselves on Vine with their 6-second musical covers and arrangements ʹ gaining over 3.9 million followers. -

Final Nominations List

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 57th Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year October 1, 2013 through September 30, 2014 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 Record Of The Year Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) and/or Mixer(s) and mastering engineer(s), if other than the artist. 1. FANCY Iggy Azalea Featuring Charli XCX The Arcade & The Invisible Men, producers; Anthony Kilhofler & Eric Weaver, engineers/mixers; Miles Showell, mastering engineer Track from: The New Classic [Def Jam Recordings] 2. CHANDELIER Sia Greg Kurstin & Jesse Shatkin, producers; Greg Kurstin, Manny Marroquin & Jesse Shatkin, engineers/mixers; Emily Lazar, mastering engineer Track from: 1000 Forms Of Fear [RCA Records / Monkey Puzzle Records] 3. STAY WITH ME (DARKCHILD VERSION) Sam Smith Steve Fitzmaurice, Rodney Jerkins & Jimmy Napes, producers; Steve Fitzmaurice, Jimmy Napes & Steve Price, engineers/mixers; Tom Coyne, mastering engineer [Capitol Records] 4. SHAKE IT OFF Taylor Swift Max Martin & Shellback, producers; Serban Ghenea, John Hanes, Sam Holland & Michael Ilbert, engineers/mixers; Tom Coyne, mastering engineer [Big Machine Records] 5. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS Meghan Trainor Kevin Kadish, producer; Kevin Kadish, engineer/mixer; Dave Kutch, mastering engineer [Epic Records] © The Recording Academy 2014 - all rights reserved 1 Not for copy or distribution 57th Finals - Press List General Field Category 3 Category 4 Song Of The Year Best New Artist A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was first released or For a new artist who releases, during the eligibility year, the first if it first achieved prominence during the Eligibility Year. -

Bleachers Releases 'Terrible Thrills'

BLEACHERS RELEASES “TERRIBLE THRILLS” VOL. 2: AN ALL FEMALE REIMAGINING OF THEIR DEBUT ALBUM STRANGE DESIRE CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD ! Bleachers’ Jack Antonoff says: “terrible thrills vol. 2 i love female voices. i wish i had one. when i write songs i typically hear things in a female voice and then match it an octave lower so i can hit the notes. that's why so many bleachers' songs are sung so low. i could change the key but i like things sounding like a male version of what in my head was a female-sung song. I've always written this way. so with that in mind i wanted to release a version of my record that spoke to how it was written and the ways i originally heard it in my head before i recorded and sang it. i think it's important for people to know where the songs come from and why the songs come out sounding the way they do. i hear my music as my interpretation of a song I'm writing as a female in my head, so i wanted to make that a reality with the artists who inspire me to write in the first place. i first had this specific idea 6 years ago when i was making the 3rd steel train album. that's why this is volume 2 --- because volume 1 happened for the self titled steel train album. the "terrible thrills" concept is something i see being a thread through different bands and projects i do. its non specific to any band or record - it's just speaks to the way i hear music. -

Men's Basketball Team Takes Provincials, Off to Nationals

NAITSA’S GRUB CRAWL – MARCH 22 THE Please recycle this Thursday, March 10, 2011 newspaper when you are Volume 48, Issue 21 finished with it. NUGGETYOUR STUDENT NEWSPAPER EDMONTON, ALBERTA, CANADA NAIT OOKS WIN! Men’s basketball team takes provincials, off to nationals – story page 8 Photo by Jacqueline Burvill NEW STUDENTS’ ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVES NAITSA’s newly elected executives get together for a photo this week. President Govind Pillai, front left, sits with VP Campus Life Tyler Bernard, front right, VP External Timothy Jobs, back left and VP Academic Teagan Gahler. 2 The Nugget Thursday, March 10, 2011 NEWS&FEATURES Evening of inspiration By EVE KOESTER hard work really does pay off. More and more women are taking the trades by The Women in Technology sessions are meant to storm. Many other non-traditional fields of study motivate the women of NAIT. are also in popular pursuit among women, and the “Ultimately we hope students will recog- Women in Technology group is the glue that holds nize their own possibilities regarding their future them all together – figuratively speaking, that is. dreams,” says Michele Parker, Co-ordinator of Stu- The group holds monthly seminars at NAIT dent Engagement, on what can be expected. Women especially for the ladies in these types of fields. who work in industries that are dominated by men From construction to business and everything in are encouraged to enjoy the presentations and the between, the keynote speakers are sure to deliver company of others. inspirational advice. There are many exciting careers out there starv- The next anticipated guest speaker has quite a ing for female presence. -

Bleachers' Jack Antonoff to Executive Produce

BLEACHERS’ JACK ANTONOFF TO EXECUTIVE PRODUCE SOUNDTRACK FOR 20TH CENTURY FOX FILM LOVE, SIMON PRE-ORDER AVAILABLE NOW FIRST SINGLE “ALFIE’S SONG (NOT SO TYPICAL LOVE SONG)”, BY BLEACHERS AVAILABLE NOW—CLICK HERE TO LISTEN (Los Angeles, CA)—Today, Bleachers release the first single off of the soundtrack for the forthcoming 20th Century Fox film, Love, Simon entitled “Alfie’s Song (Not So Typical Love Song)” via RCA Records. The soundtrack, which is being executive produced by Bleachers’ Jack Antonoff, will be released on March 16th, 2018 via RCA Records and is available for pre-order now at all digital retail providers. “Alfie’s Song (Not So Typical Love Song)” will also be available as an instant grat for those who pre-order the album. See full track listing below. Click HERE to listen. Love, Simon Soundtrack Track Listing: 1. Alfie’s Song (Not So Typical Love Song) Bleachers 2. Rollercoaster Bleachers 3. Never Fall In Love Jack Antonoff & MØ 4. Strawberries & Cigarettes Troye Sivan 5. Sink In Amy Shark** 6. Love Lies Khalid & Normani 7. The Oogum Boogum Song Brenton Wood 8. Love Me The 1975 9. I Wanna Dance With Somebody Whitney Houston 10. Someday At Christmas Jackson 5 11. Wings Haerts 12. Keeping A Secret Bleachers* 13. Wild Heart Bleachers *DOES NOT APPEAR IN FILM **VERSION DOES NOT APPEAR IN FILM About Love, Simon Everyone deserves a great love story. But for seventeen-year old Simon Spier it's a little more complicated: he's yet to tell his family or friends he's gay and he doesn't actually know the identity of the anonymous classmate he's fallen for online.