Crime Displacement in King's Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C02648 A3L Alan Wito Dartmouth Park CA

W E us S mp A T a RC H y C ing HW I wa ild A L h u Y 5 E L E rc ll B RO 5 l LAC 6 P S e A e AD P A u Th enw CR R b rk 3 S le Sl 3 1 K ta C M 8 H A 1 2 I W H 7 G ar RS 59.0m d Bd E al H y 7 it AV El sp G H 95.4m Highgate Cemetery Ho ) g A 8 Whittington Hospital Sub Sta on in 9 gt W T 1 in 's F 84.9m 0 tt y E 8 i r 9 1 I 2 h a S Diving Platform T M W t H 9 Z (Highgate Wing) (S EW R IL M 8 O 0 L S Y ER 3 W P Tank 5 Y O A A 7 FB FL R 8 W K 1 6 E 1 S 2 E 1 2 1 PH 1 N 3 St James Villa 1 U A t O L o H 4 4 L A N 2 2 8 L O 2 99.3m r T O c Fitzroy T h Archway R w E 5 1 a M 3 y 9 Methodist Lodge C l o 9 3 s Central Shelter 1 e 8 1 Playground T Hall 0 7 C 21 5 B 84.8m to to 59.3m 184 1 T 81.5m E a n V Archway k 2 Chy O 4 183 0 R 7 to 4 Tavern 15 2 G o E t Surgery N 1 I U (PH) 1 in Apex N B 57.4m ra E C O 6 V 7 15 e D 3 A Lodge to ns s n 6 R 0 3 io en A 2 s 7 2 1 an rd 8 t 8 L a t r M o Mortuary ta ge t G 9 S A a 9 Lod lo 7 b y Lu u D l o 4 oll S G H t H l 3 22 E A a 5 1 to M ll 89 71.9m Ban B tre k u en il ily C D d 3 5 i am 8 Chy n 5 F 7 UE 91.5m to N A g 3 7 5 E 5 V s TT A 4 O B 9 O SH E o t 4 3 K AK o PCs 5 r O R 6 FB 5 o R 81.6m 8 t 8 A 4 o 5 7 o C El Sub Sta P 28 t 7 L o D IL n L H s 3 78.6m S t T 3 B C e , A S T c A a G E 27 Pl N PCs o r e y L t a 1 W c r D 1 t t N s e o R 1 a 3 1 0 u R A 5 r 7 7 FB 1 o t o s I o t b O i D 4 1 l 0 1 H 6 8 1 y L G 2 1 FB D n A C r E 2 y ch C w 5 s k l ay ion o l R S s 3 a C n n 4 m a 5 56.0m t T T M o o e a w s 3 g 7 W e R d 6 r Lo t A H ly y E 2 l o & Govt 83.9m H le E 1 2 s M 6 m L t 2 T 3. -

Prime Bloomsbury Freehold Development Opportunity LONDON

BLOOMSBURY LONDON WC2 LONDON WC2 Prime Bloomsbury Freehold Development Opportunity BLOOMSBURY LONDON WC2 INVESTMENT SUMMARY • Prime Bloomsbury location between Shaftesbury Avenue and High Holborn, immediately to the north of Covent Garden. • Attractive period building arranged over lower ground, ground and three upper floors totalling 10,442 sq ft (970.0 sq m) Gross Internal Area. • The property benefits from detailed planning permission, subject to a Section 106 agreement, for change of use and erection of a roof extension to six residential apartments (C3 use) comprising 6,339 sq ft (589.0 sq m) Net Saleable Area and four B1/A1 units totalling 2,745 sq ft (255.0 sq m) Gross Internal Area, providing a total Gross Internal Area of 12,080 sq ft (1,122.2 sq m). • The property will be sold with vacant possession. • The building would be suitable for owner occupiers, developers or investors seeking to undertake an office refurbishment and extension, subject to planning. • Freehold. • The vendor is seeking offers in excess of £8,750,000 (Eight Million, Seven Hundred and Fifty Thousand Pounds) subject to contract and exclusive of VAT, which equates to £838 per sq ft on the existing Gross Internal Area and £724 per sq ft on the consented Gross Internal Area. BLOOMSBURY LONDON WC2 LOCATION The thriving Bloomsbury sub-market sits between Soho to the west, Covent Garden to the south and Fitzrovia to the north. The local area is internationally known for its unrivalled amenities with the restaurants and bars of Soho and theatres and retail provision of Covent Garden a short walk away. -

Queens Crescent, Kentish Town

Queens Crescent, Kentish Town NW5 Internal Page1 Single Pic Inset A beautiful 4 bedroom 2 bathroom family home on a quiet tree lined Crescent conveniently located between Hampstead Heath and Kentish Town. FirstThis familyparagraph, home editorialhas been style, refurbished short, consideredto a high standard headline by the benefitscurrent owners of living and here. comprises One or two on thesentences ground thatfloor conveyof an open what you would say in person. plan reception room with a fireplace, fully integrated eat-in Secondkitchen diner,paragraph, private additional garden and details guest of W/C.note aboutOn the the first floor are property.2 double Wordingbedrooms to andadd avalue large and family support bathroom, image whilst selection. on the Temsecond volum floor is aresolor 2 furthersi aliquation double rempore bedrooms puditiunto (1 with an qui en-suite utatis adit,bathroom). animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. ThirdThe house paragraph, has a additional loft that could details be ofconverted note about subject the property. to the Wordingnecessary to planningadd value permissions. and support image selection. Tem volum is solor si aliquation rempore puditiunto qui utatis adit, animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. 4XXX2 1 X GreatQueens Missenden Crescent is1.5 located miles, London 0.3 miles Marlebone to Chalk Farm 39 minutes, AmershamUnderground 6.5 Station miles, M40 (Northern J4 10 miles,Line) and Beaconsfield 0.4 miles to11 Kentishmiles, M25Town j18 West 13 miles, Station. Central It is also London within 36 easy miles reach (all distances of Hampstead and timesHeath, are Belsize approximate). -

London Borough of Camden March 2021 Detailed Scheme Information

MURPHY’S YARD LONDON BOROUGH OF CAMDEN DETAILED SCHEME INFORMATION MARCH 2021 HYBRID PLANNING APPLICATION The proposals are intended to be submitted in a How do we know that the outline elements will be consistent with the Why is flexibility being sought? vision for the site? Hybrid Planning Application to LB Camden. Due to The proposed uses within the employment uses are envisaged to be the scale of the project, the planning application will A Design Code is being produced which will set out the overarching complementary in order to create a vibrant, sustainable and inviting design principles which later planning applications need to adhere to. workspace environment. We are proposing flexibility within the also be considered by the GLA in addition to statutory workspaces in order to have the ability through the detailed design of This will include elements such as the architectural intent, the delivery these outline plots to develop this narrative more granularly, in order stakeholders. of the heathline, the massing approach, and so on. to curate a successful and dynamic place to work and visit. What is a Hybrid Planning Application? What does this mean for the heights and massing of the buildings in This is a planning application which consists of elements, some of the outline element of the planning application? which are in detail and some in outline. The planning application will be accompanied by parameter plans, which set out the proposed use, maximum mass and maximum heights of the plots. What’s the difference between detail and outline? It is envisaged that different architects will take on the detailed A detailed planning application contains all the information of the applications for different plots in the outline elements. -

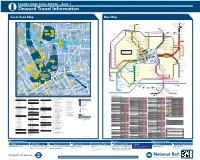

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Programmes and Investment Committee

Programmes and Investment Committee Date: 8 March 2017 Item: Investment Programme Report – Quarter 3, 2016/17 This paper will be considered in public 1 Summary 1.1 The Investment Programme Report describes the progress and performance in Quarter 3, 2016/17 of a range of projects that will deliver world-class transport services to London. 1.2 Quarter 3, 2016/17 covers the months of October to December 2016. 2 Recommendation 2.1 The Committee is asked to note the report. List of appendices to this report: Appendix 1 – Investment Programme Report Quarter 3, 2016/17. List of Background Papers: None Contact Officers: Leon Daniels, Managing Director Surface Transport Mark Wild, Managing Director London Underground Number: 020 3054 0180 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Transport for London investment programme report Quarter 3 2016/17 Contents About Transport for London (TfL) 4 Introduction 24 Buses Part of the Greater London Authority We work hard to make journeys easier family of organisations led by Mayor through effective use of technology and 6 Business at a glance 27 Rail of London Sadiq Khan, we are the data. We provide modern ways to pay integrated transport authority through Oyster and contactless payment responsible for delivering the Mayor’s cards and provide information in a wide 8 Key achievements 30 Roads strategy and commitments on transport. range of formats to help people move around London. As a core element in the Mayor’s overall 9 2016/17 Budget 39 Other operations plan for London, our purpose is to keep Real-time travel information is provided milestone performance London moving, working and growing, directly by us and through third party and to make life in our city better. -

Units 1 & 2 Hampstead Gate

UNITS 1 & 2 HAMPSTEAD GATE FROGNAL | HAMPSTEAD | LONDON | NW3 FREEHOLD OFFICE BUILDING FOR SALE AVAILABLE WITH FULL VACANT POSSESSION & 4 CAR SPACES 3,354 SQFT / 312 SQM (CAPABLE OF SUB DIVISION TO CREATE TWO SELF CONTAINED BUILDINGS) OF INTEREST TO OWNER OCCUPIERS AND/OR INVESTORS www.rib.co.uk INVESTMENT SUMMARY www.rib.co.uk • 2 INTERCONNECTING OFFICE BUILDINGS CAPABLE OF SUB DIVISION (TWO MAIN ENTRANCES) • 4 CAR PARKING SPACES • CLOSE PROXIMITY TO FINCHLEY ROAD UNDERGROUND STATION AND THE O² CENTRE • FREEHOLD • AVAILABLE WITH FULL VACANT POSSESSION SUMMARY www.rib.co.uk F IN C H LE Y HAMPSTEAD R F O I A GATE T EST D Z J HAMPSTEAD O Belsie Park H N H ’ A S V E A R V S Finchle Rd & Fronall T E O N CK U H E IL West Hampstead 2 L W O2 Centre E S ESIE PA T Finchle Rd E N D SUTH Swiss Cottae Chalk Farm L A D K HAMPSTEAD E ROA IL N AID BURN DEL E A HI OAD G E R H SIZ RO L E B F A I D N C H L E Y A B R A O V PIMSE HI B E E A Y N D D A R U RO E RT O E A R LB D O A A CE St ohns Wood D IN PR M IUN A W ID E A L L V I A N L G E T O EGENTS PA N R O A D LOCATION DESCRIPTION Hampstead Gate is situated close to the junction with Frognal and Comprise two interconnecting office buildings within a purpose-built Finchley Road (A41) which is one of the major commuter routes development. -

Sheltered Housing Schemes in Camden Contents

Sheltered housing schemes in Camden Contents Page What is sheltered housing? .........................................................................................3 Other services for older people in Camden ..............................................................4 Other sheltered housing options in Camden ............................................................5 Map of scheme locations and schemes listed alphabetically .................................6 Scheme information .....................................................................................................8 Sheltered schemes listed by area Hampstead and Swiss Cottage Page Number Argenta ...........................................................................................................................9 Henderson Court ..........................................................................................................10 Monro House ................................................................................................................11 Robert Morton House ..................................................................................................12 Rose Bush Court ..........................................................................................................13 Spencer House .............................................................................................................14 Waterhouse Close ........................................................................................................15 Wells Court ...................................................................................................................16 -

Railways: Thameslink Infrastructure Project

Railways: Thameslink infrastructure project Standard Note: SN1537 Last updated: 26 January 2012 Author: Louise Butcher Section Business and Transport This note describes the Thameslink infrastructure project, including information on how the scheme got off the ground, construction issues and the policy of successive government towards the project. It does not deal with the controversial Thameslink rolling project to purchase new trains to run on the route. This is covered in HC Library note SN3146. The re- let of the Thameslink passenger franchise is covered in SN1343, both available on the Railways topical page of the Parliament website. The Thameslink project involves electrification, signalling and new track works. This will increase capacity, reduce journey times and generally expand the current Thameslink route through central London and across the South East of England. On completion in 2018, up to 24 trains per hour will operate through central London, reducing the need for interchange onto London Underground services. The project dates back to the Conservative Government in the mid-1990s. It underwent a lengthy public inquiry process under the Labour Government and has been continued by the Coalition Government. However, the scheme will not be complete until 2018 – 14 years later than its supporters had hoped when the scheme was initially proposed. Contents 1 Where things stand: Thameslink in 2012 2 2 Scheme generation and development, 1995-2007 3 2.1 Transport and Works Act (TWA) Order application, 1997 5 2.2 Revised TWA Order application, 1999 6 2.3 Public Inquiry, 2000-2006 6 2.4 New Thameslink station at St Pancras 7 This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

86 Mill Lane

AVAILABLE TO LET 86 Mill Lane 86 Mill Lane, West Hampstead, London NW6 1NL Prominent retail shop in the heart of Mill Lane West Hamsptead 86 Mill Lane Prominent retail shop in the Rent £14,500 per annum heart of Mill Lane West Rates detail The property will need to Hamsptead be re assessed for Business Rates following Mill Lane is a popular street in West Hampstead and the refurbishment. benefits from a wide range of retailers and is favoured by professionals with Accountants, Surveyors and Building type Retail Opticians close by. Planning class A1 86 Mill Lane has undergone a complete refurbishment and benefits from a new kitchenette and w/c. Both the Secondary classes A2 ground and basement are open plan. The office could be suitable for both A1 and A2 Size 416 Sq ft occupiers. VAT charges No VAT payable on the Available now. rent. Lease details A new Full Repairing and Insuring lease Outside the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 for a term by arrangement. EPC category C EPC certificate Available on request Marketed by: Dutch & Dutch For more information please visit: http://example.org/m/39855-86-mill-lane-86-mill-lane 86 Mill Lane Recently refurbished shop / office Brand new kitchenette and W/C Forecourt Ample pay and display parking on Mill Lane Located close to the Hillfield Road (CS bus stop) 11 ft frontage Spot lights No VAT 86 Mill Lane 86 Mill Lane 86 Mill Lane, 86 Mill Lane, West Hampstead, London NW6 1NL Data provided by Google 86 Mill Lane Floors & availability Floor Size sq ft Status Ground 238 Available Basement 178 Available Total 416 Location overview The premises is situated mid-way along Mill Lane in West Hampstead on the southern side of the thoroughfare between the junction of Broomsleigh Street and Ravenshaw Street. -

EVERSHOLT STREET London NW1

245 EVERSHOLT STREET London NW1 Freehold Property For Sale Well let restaurant and first floor flat situated in the Euston Regeneration Zone Building Exterior 245 EVERSHOLT STREET Description 245 Eversholt Street is a period terraced property arranged over ground, lower ground and three upper floors. It comprises a self-contained restaurant unit on ground and lower ground floors and a one bedroom residential flat at first floor level. The restaurant is designed as a vampire themed pizzeria, with a high quality, bespoke fit out, including a bar in the lower ground floor. The first floor flat is accessed via a separate entrance at the front of the building and has been recently refurbished to a modern standard. The second and third floor flats have been sold off on long leases. Location 245 Eversholt Street is located in the King’s Cross and Euston submarket, and runs north to south, linking Camden High Street with Euston Road. The property is situated on the western side of the north end of Eversholt Street, approximately 100 metres south of Mornington Crescent station, which sits at the northern end of the street. The property benefits from being in walking distance of the amenities of the surrounding submarkets; namely Camden Town to the north, King’s Cross and Euston to the south, and Regent’s Park to the east. Ground Floor Communications The property benefits from excellent transport links, being situated 100m south of Mornington Crescent Underground Station (Northern Line). The property is also within close proximity to Camden Town Underground Station, Euston (National Rail & Underground) and Kings Cross St Pancras (National Rail, Eurostar and Underground).