FV2 1 Marjory's War Introduction Marjory Stephenson Made Her

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holding Hands with Bacteria the Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN MOLECULAR SCIENCE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY Soňa Štrbáňová Holding Hands with Bacteria The Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson 123 SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science History of Chemistry Series editor Seth C. Rasmussen, Fargo, North Dakota, USA More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10127 Soňa Štrbáňová Holding Hands with Bacteria The Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson 1 3 Soňa Štrbáňová Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Prague Czech Republic ISSN 2191-5407 ISSN 2191-5415 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science ISSN 2212-991X SpringerBriefs in History of Chemistry ISBN 978-3-662-49734-0 ISBN 978-3-662-49736-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-49736-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934952 © The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Studies on the in Vitro Digestion of Cellulose By

STUDIES ON THE IN VITRO DIGESTION OF CELLULOSE BY RUIvIEN MICROORGANISMS By ROBERT LAWRENCE SALSBURY A THESIS Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Dairy 1955 ProQuest Number: 10008419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10008419 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 STUDIES ON THE IN VITRO DIGESTION OF CELLULOSE BY RUMEN MICROORGANISMS By ROBERT LAURENCE SALSBURY rjmiirr AN ABSTRACT Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Dairy Year 1955 Approved 1 Four methods of incubating rumen fluid for the purpose of studying cellulose digestion in vitro were examined. Under the conditions used, it was found that the maximum cellulose digestion and most reproducible results were obtained when a semipermeable sac was used and the inoculum: mineral-solution ratio was small. -

Early Women Biochemists >> Marjory Stephenson

Early Women Biochemists >> Marjory Stephenson 6 Marjory Stephenson (left) and Dorothy Needham in academic robes, c. 1948. Cambridge University Archives, Biochemistry Department Photograph Albums. Recognition Taking a pragmatic and purposeful approach to life, Marjory Stephenson had little time for pride or egotism in others. Joan Mason relays the aside that she used to make fun of her male colleagues ‘fussing about their reputations... as if they were aging virgins in a Victorian novel’.1 In publication, she would take credit where credit was due – her name appeared only when she felt she had contributed sufficiently to the final outcome.2 Nevertheless, Stephenson herself was recognised for her achievements in the form of scholarships, awards, memberships, appointments and honorary degrees. Having obtained an MBE in recognition of her humanitarian war-work (December 1918), Stephenson waited many more years for similar recognition within the scientific community. For many years during the 1920s, Stephenson existed on annually-renewed Medical Research Council (MRC) grants. In 1929, the MRC recruited Stephenson to its external staff and in 1936 Cambridge awarded her an ScD degree for outstanding research.3 Even so, it was not until 1943 that Cambridge finally appointed Stephenson to a university lectureship, at the age of 58. Perhaps most significant to the history of women in science was Stephenson’s Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS). In a further reflection of Stephenson’s aversion to the rituals of status, she chose to leave the country to avoid further publicity when her nomination was announced.4 It was then awarded to Stephenson in 1945, who became the first woman FRS (alongside that of Kathleen Lonsdale). -

3. Hopkins's Protégé

Early Women Biochemists >> Marjory Stephenson 3 Frederick Gowland Hopkins, c. 1943. Cambridge University Archives, Biochemistry Department Photograph Albums. Hopkins’s protégé A characterful portrait of Frederick Gowland Hopkins (1861-1947), taken towards the end of his life in c. 1943. It was Hopkins who mentored Stephenson at a critical period in her career after 1919. From 1919, Stephenson worked on vitamins and nutrition with Hopkins at Cambridge. It was on his advice that she switched to bacterial metabolism. According to the historian Robert Kohler, this fitted with Hopkins’s grand schema for ‘general biochemistry’ and provided a ready-made niche for Stephenson to ‘push beyond the limits of the biochemical tradition’. Equally, Kohler has also suggests that ‘the substance that Stephenson gave to the new field... was distinctly her own’.1 The acknowledgements to Stephenson’s Bacterial Metabolism (1930) recorded her debt of gratitude to Hopkins, at whose suggestion, she claimed, ‘the book was written and to whose influence alone I owe the incentive to think on biochemical matters’.2 Stephenson’s biographers, however, have also noted that she was an energetic independent investigator, who according to Robertson ‘took her fair share in the hard work of the subject’.3 By the 1940s, any deference Stephenson felt for Hopkins appears to have transmuted into a mutual respect. Her obituarist, D.D. Woods noted in 1950 that whilst her admiration for ‘Hoppy’ remained undiminished, she had become a ‘great standby to Hopkins in the running of his department, in which she had by then become a leading personality’.4 1 Robert Kohler, ‘Innovation in Normal Science: Bacterial Physiology’, Isis 76 (1985), pp. -

Marjory Stephenson Obituary Notice

*No*2, Volume 3 of the Journal of General Microbiology was issued on 24 June 1949 Obituary Notice MARJORY STEPHENSON, 1885-1948 The death of Marjory Stephenson on 12 December 1948 has robbed bio- chemistry of a vigorous and productive exponent, and microbiology of a valuable interpreter of the chemical way of thinking. She was born on 24 January 1885 at Burwell, twelve miles from Cambridge; her life centred on Cambridge; she knew the town well and was well known in it. After graduating from Newnham she had hoped to complete a medical course but found it necessary to study Domestic Science at the Gloucestershire Training College instead, and she taught for a time there and at King’s College of Household Science, London. Her career as a biochemist started at University College, London, working with R. H. A. Plimmer. In later life she always spoke of him with gratitude for providing her with this opportunity. She there studied the lactase of intestinal mucosa and showed that this enzyme was inhibited by glucose but not by galactose (Stephenson, 1911). She turned next to the synthesis of esters of palmitic acid (Stephenson, 1913) and then worked on metabolism in experimental diabetes (Moorhouse, Paterson & Stephenson, 1915). This work was interrupted by the 1914-18 war, during which she served with the Red Cross in France and at Salonika. After the war she returned to Cambridge and worked in the department of Frederick Gowland Hopkins on the fat-soluble vitamins (Stephenson & Clark, 1920; Stephenson, 1920). Hopkins in his wisdom encouraged her to leave the fields of animal metabolism and vitamins and to initiate a comprehensive study of the biochemical activities of bacteria. -

Chemical Microbiology, an Interdisciplinary Field on the Road to Molecular Biology, 1920-1948

Chemical Microbiology, an Interdisciplinary Field on the Road to Molecular Biology, 1920-1948 Sonˇ a Sˇ trbánˇová* Since the second half of the 19th century scientific development has been charac- terised among others by intense integration and differentiation of scientific disci- plines resulting in the evolvement of new interdisciplinary sciences and fields. This is also true about chemistry which has interacted with numerous other dis- ciplines and fields with serious consequences for the structure of scientific disci- plines which was this way enriched with new interdisciplinary fields and sciences. Although a number of authors attempted to characterise and analyse the notions of “scientific discipline”, “interdisciplinary science” or “interdisciplinary field”,1 historians of science still have not agreed on their generally acceptable defini- tions. This paper is aimed at contributing to this discussion using the example of emergence of chemical microbiology which became constituted between 1930 and 1950, approximately, on the boundary of several chemical and biological disciplines. From biochemistry to chemical microbiology In order to understand the genesis of chemical microbiology it is necessary to recall a few particulars related to the formation of biochemistry, one of its “par- ent” interdisciplinary sciences, which dominated the scientific scene in the first half of the 20th century.2 As many historians have agreed, biochemistry became an independent discipline after 1900 with all necessary attributes: an institutional and communication base, an international scientific community, an independent subject taught in a number of universities, with a specific social mission and social acknowledgement and various strategic concepts outlining its program. The most significant for the future development of biochemistry, and will be seen, also for chemical microbiol- * Institute of Contemporary History, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Pusˇkinovo nám 9, 160 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic. -

TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’S Inspirational Women TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’S Inspirational Women Introduction

TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’s Inspirational Women TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’s Inspirational Women Introduction A trailblazer is someone who goes ahead to find a way through Key categories unexplored territory leaving markers behind which others can follow. They are innovators, the first to do something. During Arts & Culture the First World War many women were trailblazers. Even today their inspirational stories can show us the way. Activism The First World War was a time of political and social change for women. Before the war began, women were already Science protesting for the right to vote in political elections, this is known as the women’s suffrage movement. There were two main forms of women’s suffrage in the UK: the suffragists and Industry the suffragettes. Military In 1897 seperate women’s suffrage societies joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies Definitions (NUWSS) which was led by Millicent Fawcett. Suffragists believed that women could prove they should have the right Suffrage: to vote by being responsible citizens. The right to vote in political elections The suffragettes broke away from the suffragist movement and Munition: formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) under Military weapons, bullets, Emmeline Pankhurst. They believed it was necessary to use and equipment illegal means to force a change in the law. Prejudice: When the war started, campaigners for women’s rights set Dislike or hostility aside their protests and supported the war effort. Millions without good reason of men left Britain to fight overseas. Women took on more Activism: public responsibilities. -

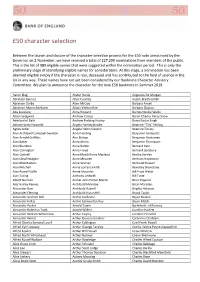

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

Sir Fredrick Gowland Hopkins: the Father of Biochemistry

Sir Fredrick Gowland Hopkins: The Father of Biochemistry 28 November 2013 | Column | By Hiteshi Dhami-Shah Sir Hopkins best remembered for his discovery of ‘vitamins’ has contributed immensely to the field of biochemistry, which was initiated as physiological chemistry on the continent. It is difficult to discuss in detail all the significant discoveries made by him in this article. Some of the most important discoveries, which shaped the field of biochemistry, are highlighted by Hiteshi Dhami-Shah, a Clinical Nutritionist and Research Fellow at Kasturba Health Society – Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, in this article. The discovery and establishment of dynamic biochemistry as a subject can be credited to Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins. Popularly known as the ‘father of biochemistry’, Hopkins is best remembered for his discovery of ‘vitamins’, with Christiaan Eijkman, for which they were jointly, awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1929. In addition to the Nobel Prize, Hopkins was conferred with numerous awards like the Royal Medal and the Copley Medal of the Royal Society, Fellowship of the Royal Society, knighthood by King George V and the award of the Order of Merit. Inspite of having such an illustrious career, his life has enough struggles. Probably, the early hardship in life prepared him to earn laurels in later life, with grace and dignity. Frederick Gowland Hopkins was born in Eastbourne, England on June 20, 1861. Ever Sir Fredrick Gowland Hopkins since early childhood his inclination towards science was evident. This can be observed from his childhood tryst with his father’s microscope. He later wrote for the microscope that; ‘It was the most important thing I had yet come up against; so much more significant than anything I was being taught at school’. -

1 Marjory Stephenson Scd FRS (1885-1948)

Marjory Stephenson ScD FRS (1885-1948) Introduction As Head of the Biochemistry Department in Cambridge in the early years of the twentieth century, Frederick Gowland Hopkins encouraged and recruited a number of women scientists. One of the most distinguished was Marjory Stephenson who later became the first woman biological scientist to be elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1945, for her work on bacterial metabolism. Marjory’s research career started late because at first she had to earn a living through teaching; it was also interrupted by the First World War in which she served abroad with the British Red Cross Society. So it was not until January 1919 (the month of her 34th birthday) that Marjory joined Hopkins’ Department, where, for the next 30 years, she played a leading role in developing biochemical studies in bacteria. There was no conventional career path for academic scientists in the early part of the 20th century, especially for women in Cambridge where the University was the last in the country to admit women to full membership on equal terms with men – that happened in 1948, the year that Marjory died. It has been suggested that, at this time, women were more likely to find their place in new disciplines such as biochemistry and X-ray crystallography because ambitious young men with families to support considered those fields to be too risky, both scientifically and financially (1). Although Marjory did not have all the opportunities open to the men of her generation, she was skilful in making the most of those that came her way. -

··COMMENTARY by Bernard Dixon

© 1986 Nature Publishing Group http://www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology • ··COMMENTARY by Bernard Dixon A SALUTE TO THE PIONEERS OF MICROBIOLOGY efore we lose sight of our the whooping cough bacillus in the laboratory. Among the Bgood fortune amidst the galaxy of other speakers were Hans Zinsser, author of freneticism of patents, probes, Rats, Lice and History; Peyton Rous and Robert Shope, and what Spyros Andreopou discoverers of the virus-induced tumors which bear their los calls "gene cloning by press names; Fred Griffith, whose 1928 demonstration of trans conference" (See New England formation in pneumococci was an essential prelude to the Journal of Medicine 302:743, double helix of Watson and Crick; and Jan Kluyver and 1980), let's pause and remem- C. B. van Neil, authors of that splendid book The Microbe's ber one thing. Microbiology is Contribution to Biology. young. Measured alongside Penicillin observer Alexander Fleming and tobacco mo other strands of human endea saic virus purifier Wendell Stanley were there. So too were vour, it has not eveh touched Max Theiler, the originator of yellow fever vaccine; upon middle age. While all sci Arthur Harden, who took the initial steps in dissecting out entists stand on the shoulders of their forebearers in the biochemistry of alcoholic fermentation; Otto Myerhof, advancing understanding, generation by generation, only who unpickled lactic acid metabolism in muscle; and microbiologists have an almost immediate sense of affinity Marjory Stephenson, who fashioned the pursuit of micro with the people who created their craft. bial physiology almost single-handedly (See Bio/Technology Macrobiologists, for example, need to peer back way 3:959, November, 1985). -

Early Women Biochemists >> Marjory Stephenson

Early Women Biochemists >> Marjory Stephenson 5 Cartoon detail from ‘M.S.’, ‘Down the Microscope and What Alice Found There’, Brighter Biochemistry 5 (December 1927). Wellcome Library, Biochemical Society, Brighter Biochemistry SA/BIO/D/1/39. Flights of fancy A sketch of a deceptively friendly microbe, apparently drawn by Marjory Stephenson herself, and submitted for inclusion in Brighter Biochemistry. The drawing appeared alongside Stephenson’s suitably surreal take of Lewis Carroll’s Alice through the Looking Glass in the December 1927 issue of this in-house laboratory magazine. In Stephenson’s flight of fancy, Alice the biochemist wishes she could descend down the microscope to look for her evasive bacteria. Wish granted, Alice ends up at a bacterial court accused of belittling her subjects. Previously the examiner, Alice becomes the examined. The microbial magistrate condemns the human race to ‘death by autoclaving at 20lbs pressure for 30 minutes’ and poor Alice is then stained and counterstained, decolourized, washed in acid and alcohol and put up in Canada balsam – just as she had once done to her bacteria. Evidently a morality tale on the principle – ‘do to others as you would have them do to you’! At the time Stephenson produced this story, she was in reality on the cusp of an important discovery that would help illuminate bacterial metabolic processes. During 1928, Stephenson successfully isolated a bacterial enzyme (lactate dehydrogenase) from its host cells.1 Stephenson went on to publish these results in Bacterial Metabolism (1930) – a book that Muriel Robertson noted would have an influence ‘not only in England and America, but also abroad’ [sic!].2 In Bacterial Metabolism, Stephenson summarised the purpose of her researches as to ‘catch sight of the machinery’ that animates life.