Ubiquitin-Independent Proteolytic Targeting of Ornithine Decarboxylase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S41598-021-93055-5.Pdf

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Potent antitumor activity of a glutamyltransferase‑derived peptide via an activation of oncosis pathway Cheng Fang1,7, Wenhui Li2,7, Ruozhe Yin3,7, Donglie Zhu3, Xing Liu4, Huihui Wu4, Qingqiang Wang3, Wenwen Wang4, Quan Bai5, Biliang Chen6, Xuebiao Yao4* & Yong Chen3* Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) still presents poor prognosis with high mortality rate, despite of the improvement in the management. The challenge for precision treatment was due to the fact that little targeted therapeutics are available for HCC. Recent studies show that metabolic and circulating peptides serve as endogenous switches for correcting aberrant cellular plasticity. Here we explored the antitumor activity of low molecular components in human umbilical serum and identifed a high abundance peptide VI‑13 by peptidome analysis, which was recognized as the part of glutamyltransferase signal peptide. We modifed VI‑13 by inserting four arginines and obtained an analog peptide VI‑17 to improve its solubility. Our analyses showed that the peptide VI‑17 induced rapid context‑dependent cell death, and exhibited a higher sensitivity on hepatoma cells, which is attenuated by polyethylene glycol but not necrotic inhibitors such as z‑VAD‑fmk or necrostatin‑1. Morphologically, VI‑17 induced cell swelling, blebbing and membrane rupture with release of cellular ATP and LDH into extracellular media, which is hallmark of oncotic process. Mechanistically, VI‑17 induced cell membrane pore formation, degradation of α‑tubulin via infux of calcium ion. These results indicated that the novel peptide VI‑17 induced oncosis in HCC cells, which could serve as a promising lead for development of therapeutic intervention of HCC. -

Ftsh Is Required for Proteolytic Elimination of Uncomplexed Forms

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 4532-4536, May 1995 Cell Biology FtsH is required for proteolytic elimination of uncomplexed forms of SecY, an essential protein translocase subunit (protein translocation/quality control/proteolysis/AAA family/membrane protein) AKIO KIHARA, YOSHINORI AKIYAMA, AND KOREAKI ITO Department of Cell Biology, Institute for Virus Research, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-01, Japan Communicated by Randy Schekman, University of California, Berkeley, CA, February 13, 1995 (receivedfor review December 5, 1994) ABSTRACT When secY is overexpressed over secE or secE Overexpression of SecY from a plasmid does not lead to is underexpressed, a fraction of SecY protein is rapidly significant overaccumulation of SecY (2, 12). Under such degraded in vivo. This proteolysis was unaffected in previously conditions, the majority of SecY is degraded with a half-life of described protease-defective mutants examined. We found, about 2 min, whereas the other fraction that corresponds to the however, that some mutations inftsH, encoding a membrane amount seen in the wild-type cell remains stable (2). When protein that belongs to the AAA (ATPase associated with a SecE is co-overproduced, oversynthesized SecY is stabilized variety ofcellular activities) family, stabilized oversynthesized completely (2, 12). Mutational reduction of the quantity of SecY. This stabilization was due to a loss ofFtsH function, and SecE is accompanied by destabilization of the corresponding overproduction of the wild-type FtsH protein accelerated the fraction of newly synthesized SecY molecules (2). These degradation. The ftsH mutations also suppressed, by allevi- observations indicate that uncomplexed SecY is recognized ating proteolysis of an altered form of SecY, the temperature and hydrolyzed by a protease and that SecE can antagonize the sensitivity of the secY24 mutation, which alters SecY such that proteolysis. -

Spontaneous Tyrosinase Mutations Identified in Albinos of Three Wild Frog Species

Genes Genet. Syst. (2017) 92, p. 189–196 Albino tyrosinase mutations in frogs 189 Spontaneous tyrosinase mutations identified in albinos of three wild frog species Ikuo Miura1*, Masataka Tagami2, Takeshi Fujitani3 and Mitsuaki Ogata4 1Amphibian Research Center, Hiroshima University, 1-3-1 Kagamiyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Hiroshima 739-8526, Japan 2Gifu World Freshwater Aquarium, 1453 Kawashima-Kasadamachi, Kakamigahara, Gifu 501-6021, Japan 3Higashiyama Zoo and Botanical Gardens Information, 3-70 Higashiyama-Motomachi, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-0804, Japan 4Preservation and Research Center, The City of Yokohama, 155-1 Kawaijuku-cho Asahi-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa 241-0804, Japan (Received 1 November 2016, accepted 9 March 2017; J-STAGE Advance published date: 30 June 2017) The present study reports spontaneous tyrosinase gene mutations identi- fied in oculocutaneous albinos of three Japanese wild frog species, Pelophylax nigromaculatus, Glandirana rugosa and Fejervarya kawamurai. This repre- sents the first molecular analyses of albinic phenotypes in frogs. Albinos of P. nigromaculatus collected from two different populations were found to suffer from frameshift mutations. These mutations were caused by the insertion of a thymine residue within each of exons 1 and 4, while albinos in a third popula- tion lacked three nucleotides encoding lysine in exon 1. Albinos from the former two P. nigromaculatus populations were also associated with splicing variants of mRNA that lacked either exons 2–4 or exon 4. In the other two frog species exam- ined, missense mutations that resulted in amino acid substitutions from glycine to arginine and glycine to aspartic acid were identified in exons 1 and 3, respec- tively. The two glycines in F. -

Signal Peptide Hydrophobicity Modulates Interaction with the Twin

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/135103; this version posted May 7, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Signal peptide hydrophobicity modulates interaction with the twin- 2 arginine translocase 3 4 Qi Huang and Tracy Palmer 5 6 7 8 Division of Molecular Microbiology, School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee 9 DD1 5EH, UK 10 11 12 13 †For correspondence telephone +44 (0)1382 386464, fax +44 (0)1382 388216, e-mail 14 [email protected] 15 16 17 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/135103; this version posted May 7, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 18 Abstract 19 The general secretory pathway (Sec) and twin-arginine translocase (Tat) operate in parallel to 20 export proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane of prokaryotes and the thylakoid membrane 21 of plant chloroplasts. Substrates are targeted to their respective machineries by N-terminal 22 signal peptides that share a common tripartite organization, however Tat signal peptides 23 harbor a conserved and almost invariant arginine pair that are critical for efficient targeting to 24 the Tat machinery. Tat signal peptides interact with a membrane-bound receptor complex 25 comprised of TatB and TatC components, with TatC containing the twin-arginine recognition 26 site. -

Protein RS1 (RSC1A1) Downregulates the Exocytotic Pathway Of

Molecular Pharmacology Fast Forward. Published on August 23, 2016 as DOI: 10.1124/mol.116.104521 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. page 1, MOL #104521 Protein RS1 (RSC1A1) Downregulates the Exocytotic Pathway of Glucose Transporter SGLT1 at Low Intracellular Glucose via Inhibition of Ornithine Decarboxylase Chakravarthi Chintalapati, Thorsten Keller, Thomas D. Mueller, Valentin Gorboulev, Nadine Schäfer, Ilona Zilkowski, Maike Veyhl-Wichmann, Dietmar Geiger, Jürgen Downloaded from Groll, Hermann Koepsell Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Würzburg, 97070 Würzburg, Germany (C.C., molpharm.aspetjournals.org V.G., M.V., H.K.); Department of Molecular Plant Physiology and Biophysics, Julius-von-Sachs- Institute, University of Würzburg, 97082 Würzburg, Germany (T.K., T.D.M., N.S., D.G., H.K.); Department of Functional Materials in Medicine and Dentistry, University Hospital Würzburg, Germany (J.G., I.Z.) at ASPET Journals on September 30, 2021 Molecular Pharmacology Fast Forward. Published on August 23, 2016 as DOI: 10.1124/mol.116.104521 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. page 2, MOL #104521 Running title: Short-term Regulation of SGLT1 by RS1 via Inhibition of ODC Corresponding author: Hermann Koepsell, Department of Molecular Plant Physiology and Biophysics, Julius-von-Sachs-Institute, Julius-von-Sachs-Platz 2, 97082 Würzburg, Germany, phone +49 931 3182700; fax +49 931 31-82087; E-mail: [email protected] -

± ± Sem ± Sem ± Sem

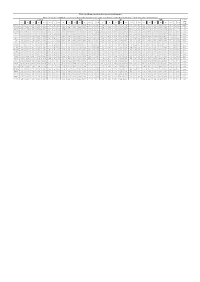

Table S10. Hematological analysis of mouse blood samples. Blood sample were treated with EDTA-K2 as an anticoagulant. The hematological analysis was performed using an Auto Hematology Analyzer BC-5390 CRP (Mindray) with the closure-whole-peripheral-blood mode. Control Soil SS MW Between groups M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 mean ± SEM M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 mean ± SEM M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 mean ± SEM M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 mean ± SEM P-value 9 WBC(10 /L) 7.46 7.85 8.17 9.04 5.61 7.63 ± 0.57 8.21 7.25 9.10 6.71 7.96 7.85 ± 0.41 5.99 9.23 6.19 8.75 7.36 7.50 ± 0.65 8.91 6.11 9.14 6.44 9.47 8.01 ± 0.72 0.93 RBC (1012/L) 9.10 8.99 8.94 8.60 8.96 8.92 ± 0.08 9.30 8.56 8.89 9.00 8.98 8.95 ± 0.12 9.00 8.84 8.89 8.71 9.21 8.93 ± 0.08 8.69 9.11 8.88 8.93 9.01 8.92 ± 0.07 1.00 HGB(g/L) 139.31 135.91 136.19 133.00 134.12 135.71 ± 1.07 139.66 133.67 135.11 136.22 135.10 135.95 ± 1.01 135.52 134.77 135.64 134.33 138.41 135.73 ± 0.71 135.71 132.47 138.11 132.14 139.34 135.55 ± 1.45 1.00 PLT(109/L) 921.23 887.55 770.00 996.12 924.29 899.84 ± 36.97 966.31 810.00 892.47 948.00 910.21 905.40 ± 27.22 1006.12 796.00 914.11 856.32 947.14 903.94 ± 36.28 841.23 997.02 914.32 801.03 936.00 897.92 ± 34.74 1.00 NE% 13.10 19.70 14.20 13.40 12.90 14.66 ± 1.28 14.49 15.03 15.49 13.11 16.21 14.87 ± 0.52 17.53 15.49 15.51 17.37 11.55 15.49 ± 1.08 15.26 14.24 10.50 16.46 16.47 14.59 ± 1.10 0.92 LY% 83.10 79.70 83.40 86.00 86.50 83.74 ± 1.22 72.58 71.26 86.16 64.33 72.61 73.39 ± 3.54 52.78 85.75 57.59 82.66 69.82 69.72 ± 6.55 85.62 56.86 91.44 57.56 88.79 76.05 ± 7.75 0.34 MO% 0.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.02 -

Escherichia Coli Clpb Is a Non-Processive Polypeptide Translocase Tao Li*, Clarissa L

Biochem. J. (2015) 470, 39–52 doi:10.1042/ BJ20141457 39 Escherichia coli ClpB is a non-processive polypeptide translocase Tao Li*, Clarissa L. Weaver*, Jiabei Lin*, Elizabeth C. Duran*, Justin M. Miller* and Aaron L. Lucius*1 *Department of Chemistry, The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham AL, U.S.A. Escherichia coli caseinolytic protease (Clp)B is a hexameric ClpA does not translocate substrate through its axial channel and AAA + [expanded superfamily of AAA (ATPase associated with into ClpP for proteolytic degradation. Rather, ClpB containing the various cellular activities)] enzyme that has the unique ability IGL loop dysregulates ClpP leading to non-specific proteolysis to catalyse protein disaggregation. Such enzymes are essential reminiscent of ADEP (acyldepsipeptide) dysregulation. Our for proteome maintenance. Based on structural comparisons to results support a molecular mechanism where ClpB catalyses homologous enzymes involved in ATP-dependent proteolysis protein disaggregation by tugging and releasing exposed tails or and clever protein engineering strategies, it has been reported loops. that ClpB translocates polypeptide through its axial channel. Using single-turnover fluorescence and anisotropy experiments we show that ClpB is a non-processive polypeptide translocase + that catalyses disaggregation by taking one or two translocation Key words: AAA motor proteins, chaperones, Forster¨ steps followed by rapid dissociation. Using single-turnover FRET resonance energy transfer (FRET), pre-steady-state kinetics, experiments we show that ClpB containing the IGL loop from protein disaggregation. INTRODUCTION ClpX being the best studied example ([11,12] and references therein). Escherichia coli caseinolytic protease (Clp)B is an ATP- Like other class 1 Hsp100/Clp enzymes, ClpB forms hexameric dependent molecular chaperone belonging to the Clp/heat-shock rings [13,14]. -

The Metabolic Profiles in Hematological Malignancies

Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus (Oct-Dec 2019) 35(4):625–634 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-019-01107-8 REVIEW ARTICLE The Metabolic Profiles in Hematological Malignancies 1 1 2 Tao Liu • Xing-Chun Peng • Bin Li Received: 13 September 2018 / Accepted: 25 February 2019 / Published online: 23 April 2019 Ó Indian Society of Hematology and Blood Transfusion 2019 Abstract Leukemia is one of the most aggressive hema- Abbreviations tological malignancies. Leukemia stem cells account for AML Acute myeloid leukemia the poor prognosis and relapse of the disease. Decades of CML Chronic myeloid leukemia investigations have been performed to figure out how to T-ALL T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia eradicate the leukemia stem cells. It has also been known B-ALL B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia that cancer cells especially solid cancer cells use energy CLL Chronic lymphocytic leukemia differently than most of the cell types. The same thing MM Multiple myeloma happens to leukemia. Since there are metabolic differences MDS Myelodysplastic syndrome between the hematopoietic stem cells and their immediate LSCs Leukemia stem cells descendants, we aim at manipulating the energy sources OXPHOS Oxidative phosphorylation with which that could have an effect on leukemia stem FAO Fatty acid oxidation cells while sparing the normal blood cells. In this review PPP Pentose phosphate pathway we summarize the metabolic characteristics of distinct Glut1 Glucose transporter 1 leukemias such as acute myeloid leukemia, chronic mye- Ara-C Arabinofuranosyl cytidine loid leukemia, T cell lymphoblastic leukemia, B-cell 2-DG 2-Deoxy-D-glucose lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia RTKs Receptor tyrosine kinases and other leukemia associated hematological malignancies ROS Reactive oxygen species such as multiple myeloma and myelodysplastic syndrome. -

List of Disorders Screened

List of Disorders Screened Amino Acid Profile (AA) Disorders Organic Acid Profile (OA) Disorders Argininemia (Arginase Deficiency) *Mitochondrial Acetoacetyl CoA Thiolase (Beta Ketothiolase/SKAT) Carbamoylphosphate Synthethase I Deficiency Deficiency Citrullinemia *Propionic Acidemia *Type I (Arginosuccinate Synthetase Deficiency) *Methylmalonic Acidemia Cobalamin Disorder (CBL A, B) Type II (Citrin Deficiency) Methylmalonic Acidemia Cobalamin Disorder (CBL C, D) *Argininosuccinate Lyase Deficiency (Argininosuccinic Aciduria) *Methylmalonyl-CoA Mutase Deficiency $Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia *Multiple CoA Carboxylase Deficiency due to Glycine Cleavage System H Protein Deficiency Malonic Aciduria (MA) due to Aminomethyltransferase Deficiency Isobutyryl CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (IBCD) due to Glycine Decarboxylase Deficiency *Isovaleric Acidemia (IVA) *Homocystinuria or variant forms of Hypermethioninemia 2 Methylbutyryl Glycinuria (2MBG) Hypermethioninemia 2 Methyl 3 Hydroxybutyric Aciduria (2M3HBA) due to Glycine N-Methyltransferase Deficiency *3 Hydroxy 3 Methylglutaryl CoA Lyase Deficiency (HMG) due to S-Adenosylhomocysteine Hydrolase Deficiency *3 Methyl Crotonyl CoA Carboxylase Deficiency (3 MCC) due to Methionine Adenosyltransferase Deficiency 3 Methylglutaconyl CoA Hydratase Deficiency (3MGA) Hyperornithinemia-Hyperammonemia-Homocitrullinuria *Glutaric Acidemia Type I (GAI) Hyperornithinemia-Hyperammonemia-Homocitrullinuria w/gyral atrophy Medium/Short Chain 3 hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase deficiency *Phenylketonuria (M/SCHAD) -

Mitochondria Targeting As an Effective Strategy for Cancer Therapy

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Mitochondria Targeting as an Effective Strategy for Cancer Therapy Poorva Ghosh , Chantal Vidal, Sanchareeka Dey and Li Zhang * Department of Biological Sciences, the University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA; [email protected] (P.G.); [email protected] (C.V.); [email protected] (S.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-883-5757 Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 6 May 2020; Published: 9 May 2020 Abstract: Mitochondria are well known for their role in ATP production and biosynthesis of macromolecules. Importantly, increasing experimental evidence points to the roles of mitochondrial bioenergetics, dynamics, and signaling in tumorigenesis. Recent studies have shown that many types of cancer cells, including metastatic tumor cells, therapy-resistant tumor cells, and cancer stem cells, are reliant on mitochondrial respiration, and upregulate oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) activity to fuel tumorigenesis. Mitochondrial metabolism is crucial for tumor proliferation, tumor survival, and metastasis. Mitochondrial OXPHOS dependency of cancer has been shown to underlie the development of resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that elevated heme synthesis and uptake leads to intensified mitochondrial respiration and ATP generation, thereby promoting tumorigenic functions in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. Also, lowering heme uptake/synthesis inhibits mitochondrial OXPHOS and effectively reduces oxygen consumption, thereby inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth in NSCLC. Besides metabolic changes, mitochondrial dynamics such as fission and fusion are also altered in cancer cells. These alterations render mitochondria a vulnerable target for cancer therapy. This review summarizes recent advances in the understanding of mitochondrial alterations in cancer cells that contribute to tumorigenesis and the development of drug resistance. -

Clpap Proteolysis Does Not Require Rotation of the Clpa Unfoldase

SHORT REPORT ClpAP proteolysis does not require rotation of the ClpA unfoldase relative to ClpP Sora Kim1†, Kristin L Zuromski2†, Tristan A Bell1†, Robert T Sauer1, Tania A Baker1* 1Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, United States; 2Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, United States Abstract AAA+ proteases perform regulated protein degradation in all kingdoms of life and consist of a hexameric AAA+ unfoldase/translocase in complex with a self-compartmentalized peptidase. Based on asymmetric features of cryo-EM structures and a sequential hand-over-hand model of substrate translocation, recent publications have proposed that the AAA+ unfoldases ClpA and ClpX rotate with respect to their partner peptidase ClpP to allow function. Here, we test this model by covalently crosslinking ClpA to ClpP to prevent rotation. We find that crosslinked ClpAP complexes unfold, translocate, and degrade protein substrates in vitro, albeit modestly slower than uncrosslinked enzyme controls. Rotation of ClpA with respect to ClpP is therefore not required for ClpAP protease activity, although some flexibility in how the AAA+ ring docks with ClpP may be necessary for optimal function. *For correspondence: Introduction [email protected] The AAA+ (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) protease subfamily uses the energy †These authors contributed of ATP hydrolysis to disassemble and degrade proteins that are misfolded, deleterious, or unneeded equally to this work (Sauer and Baker, 2011). AAA+ proteases are composed of a hexameric single- or double-ringed AAA+ unfoldase/translocase and a self-compartmentalized partner peptidase. The AAA+ rings form Competing interests: The a shallow helix and stack with planar peptidase rings (Puchades et al., 2020). -

SSIEM Classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011

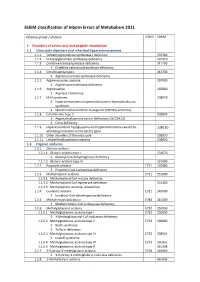

SSIEM classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011 Disease group / disease ICD10 OMIM 1. Disorders of amino acid and peptide metabolism 1.1. Urea cycle disorders and inherited hyperammonaemias 1.1.1. Carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency 237300 1.1.2. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency 237310 1.1.3. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 311250 S Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency 1.1.4. Citrullinaemia type1 215700 S Argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency 1.1.5. Argininosuccinic aciduria 207900 S Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency 1.1.6. Argininaemia 207800 S Arginase I deficiency 1.1.7. HHH syndrome 238970 S Hyperammonaemia-hyperornithinaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome S Mitochondrial ornithine transporter (ORNT1) deficiency 1.1.8. Citrullinemia Type 2 603859 S Aspartate glutamate carrier deficiency ( SLC25A13) S Citrin deficiency 1.1.9. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia caused by 138130 activating mutations in the GLUD1 gene 1.1.10. Other disorders of the urea cycle 238970 1.1.11. Unspecified hyperammonaemia 238970 1.2. Organic acidurias 1.2.1. Glutaric aciduria 1.2.1.1. Glutaric aciduria type I 231670 S Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.1.2. Glutaric aciduria type III 231690 1.2.2. Propionic aciduria E711 232000 S Propionyl-CoA-Carboxylase deficiency 1.2.3. Methylmalonic aciduria E711 251000 1.2.3.1. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency 1.2.3.2. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency 251120 1.2.3.3. Methylmalonic aciduria, unspecified 1.2.4. Isovaleric aciduria E711 243500 S Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.5. Methylcrotonylglycinuria E744 210200 S Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency 1.2.6. Methylglutaconic aciduria E712 250950 1.2.6.1. Methylglutaconic aciduria type I E712 250950 S 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency 1.2.6.2.