Removing State Constitution Badges of Inferiority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus V. Alabama, ___ F.Supp.3D ___, 2013 WL 3976626 (M.D

No. _________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- ALABAMA LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS et al., Appellants, v. THE STATE OF ALABAMA et al., Appellees. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Middle District Of Alabama --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT --------------------------------- --------------------------------- EDWARD STILL JAMES U. BLACKSHER 130 Wildwood Parkway Counsel of Record Suite 108 PMB 304 P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, AL 35209 Birmingham, AL 35201 E-mail: [email protected] 205-591-7238 Fax: 866-845-4395 PAMELA S. KARLAN E-mail: 559 Nathan Abbott Way [email protected] Stanford, CA 94305 E-mail: [email protected] U.W. CLEMON WHITE ARNOLD & DOWD P. C . 2025 Third Avenue North, Suite 500 Birmingham, AL 35203 E-mail: [email protected] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether a state violates the requirement of one person, one vote by enacting a state legislative redis- tricting plan that results in large and unnecessary population deviations for local legislative delegations that exercise general governing authority over coun- ties. ii PARTIES The following were parties in the Court below: Plaintiffs in Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-691: Alabama Legislative Black Caucus Bobby Singleton Alabama Association of Black County Officials Fred Armstead George Bowman Rhondel Rhone Albert F. Turner, Jr. Jiles Williams, Jr. Plaintiffs in consolidated Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-1081: Demetrius Newton Alabama Democratic Conference Framon Weaver, Sr. Stacey Stallworth Rosa Toussaint Lynn Pettway Defendants in Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-691: State of Alabama Jim Bennett, Alabama Secretary of State Defendants in consolidated Civil Action No. -

Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field John Herbert Roth

Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal Volume 2003 | Number 2 Article 10 Fall 3-2-2003 Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field John Herbert Roth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj Part of the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation John Herbert Roth, Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field, 2003 BYU Educ. & L.J. 739 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj/vol2003/iss2/10 . This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUCATION FUNDING AND THE ALABAMA EXAMPLE: ANOTHER PLAYER ON A CROWDED FIELD John Herbert Roth* I. INTRODUCTION If the fundamental task of the school is to prepare children for life, the curriculum must be as wide as life itself. It should be thought of as comprising all the activities and the experiences afforded by the community through the school, whereby the children may be prepared to participate in the life of the community.' During the birth of the United States, when the many notable proponents of a system of free public education in this nation envisioned the benefits of an educated multitude, it is doubtful that they could have conceived of the free public school system that has become today's reality. Although it is manifest that an educated citizenry is an objective of the utmost importance in any organized and civilized society, the debate concerning how to provide for and fund a system of free public education has continued with little repose. -

Attitudes Toward the Electability of Atheist and Nontraditional Religious Candidates

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2021 Attitudes Toward the Electability of Atheist and Nontraditional Religious Candidates Brittany Escobedo Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons, Religion Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Brittany Kali Bullock Escobedo has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Hedy Dexter, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Brandon Cosley, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Charles Diebold, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2021 Abstract Attitudes Toward the Electability of Atheist and Nontraditional Religious Candidates by Brittany Kali Bullock Escobedo Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Psychology Walden -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of IOWA No. 17-2068 DILLON CLARK

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 17-2068 DILLON CLARK, AGNES DUSABE, MUSA EZEIRIG, ZARPKA GREEN, DUSTY NYONEE, ANDABRAHAM TARPEH, Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. RYAN HOENICKE, DANIELLE WILLIAMS, CLEO BOYD, ALLEN FINCHUM, TERRY VAN HUYSEN, JIM BAILEY, MAX CARKHUFF, SCOTT GEMMELL, JERRY VANBROGEN and TPI IOWA, LLC, Defendants, INSURANCE COMPANY STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA, Defendant-Appellee. APPEAL FROM THE IOWA DISTRICT COURT FOR JASPER COUNTY THE HONORABLE TERRY RICKERS APPELLEE’S BRIEF (ORAL ARGUMENT REQUESTED) Keith P. Duffy, AT0010911 Mitchell R. Kunert, AT0004458 NYEMASTER GOODE, P.C. 700 Walnut St., Ste. 1600 Des Moines, IA 50309 ELECTRONICALLY FILED AUG 17, 2018 CLERK OF SUPREME COURT Phone: (515) 283-3100 Fax: (515) 283-8045 Email: [email protected] [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................................ 3 ISSUES PRESENTED .................................................................... 5 ROUTING STATEMENT ................................................................ 7 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ......................................................... 8 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................... 9 STANDARD OF REVIEW AND ERROR PRESERVATION .......... 9 ARGUMENT .................................................................................... 9 I. Iowa Code Section 517.5 Does Not Violate the Equal Protection Clause Contained in Article 1, Section 6 of the Iowa Constitution. ......................................................... -

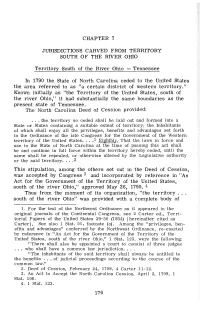

Chapter 7 Jurisdictions Carved from Territory

CHAPTER 7 JURISDICTIONS CARVED FROM TERRITORY SOUTH OF THE RIVER OHIO Territory South of the River Ohio - Tennessee In 1790 the State of North Carolina ceded to the United States the area referred to as "a certain district of western territory." Known initially as "the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," it had substantially the same boundaries as the present state of Tennessee. The North Carolina Deed of Cession provided: ... the territory so ceded shall be laid out and formed into a State or States containing a suitable extent of territory; the Inhabitants of which shall enjoy all the privileges, benefits and advantages set forth in the Ordinance of the late Congress for the Government of the Western territory of the United States ... .1 Eighthly, That the laws in force and use in the State of North Carolina at the time of passing this act shall be and continue in full force within the territory hereby ceded, until the same shall be repealed, or otherwise altered by the Legislative authority or the said territory ....2 This stipulation, among the others set out in the Deed of Cession, was accepted by Congress 3 and incorporated by reference in "An Act for the Government of the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," approved May 26, 1790. 4 Thus from the moment of its organization, "the territory . south of the river Ohio" was provided with a complete body of 1. For the text of the Northwest Ordinance as it appeared in the original journals of the Continental Congress, see 2 Carter ed., Terri torial Papers of the United States 39-50 (1934) [hereinafter cited as Carter]. -

An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama State

OCTOBER 2018 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama Constitution: 2018 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama Constitution: 2018 When voters go to the polls on November 6, they'll not only be electing a governor, legislators, and other state and local officials, they'll also be asked to vote on 19 new amendments to the Alabama Constitution of 1901. Voters statewide will decide whether to add four proposed amendments that will apply throughout the state. In addition, 15 local amendments will be voted on only in the counties in which they would apply. The Alabama Constitution is unusual. It is the longest and most amended constitution in the world. There are currently 928 amendments to the Alabama Constitution. Most state and national constitutions lay out broad principles, set the basic structure of the government, and impose limitations on governmental power. Such broad provisions are included in the Alabama Constitution. Alabama’s constitution delves into the minute details of government, requiring constitutional amendments for basic changes that would be made by the Legislature or by local governments in most states. Instead of broad provisions applicable to the whole state, about three-quarters of the amendments to the Alabama Constitution pertain to particular local governments. Amendments establish pay rates of public officials and spell out local property tax rates. A recent amendment, Amendment 921, grants municipal governments in Baldwin County the power to regulate golf carts on public streets. Until serious reforms are made, this practice will continue and the Alabama Constitution will continue to swell. -

The Lingering Bigotry of State Constitution Religious Tests Allan W

University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 3 The Lingering Bigotry of State Constitution Religious Tests Allan W. Vestal Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Allan W. Vestal, The Lingering Bigotry of State Constitution Religious Tests, 15 U. Md. L.J. Race Relig. Gender & Class 55 (2015). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc/vol15/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vestal THE LINGERING BIGOTRY OF STATE CONSTITUTION RELIGIOUS TESTS Allan W. Vestal INTRODUCTION In her Town of Greece dissent Justice Elena Kagan describes the position of a citizen who does not conform to state-sponsored religious practice: . she becomes a different kind of citizen, one who will not join in the religious practice that the Town Board has chosen as reflecting its own and the community’s most cherished beliefs. And she thus stands at a remove, based solely on religion, from her fellow citizens and her elected representatives.1 In Justice Kagan’s example, a Muslim citizen wishes to appear before the town board. Before she appears “a minister deputized by the Town asks her to pray ‘in the name of God’s only son Jesus Christ.’”2 Given the evident connection between Christian worship and the board,3 she faces a choice: . -

Special and Local Legislation Lyman H

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 4 Article 1 1936 Special and Local Legislation Lyman H. Cloe Sumner Marcus Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Cloe, Lyman H. and Marcus, Sumner (1936) "Special and Local Legislation," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 24 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol24/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY LAW JOURNAL Volume XXI1r Mlay, 1936 Number 4 SPECIAL AND LOCAL LEGISLATION By Lyx" H. CLoE* AND SumNuM MLoust With the exception of four New England states' the con- stitutions of all others contain restrictions upon local and special legislation. Uniformity in such provisions is lacking. They range in style and effect from these which appear to be no more than a declaration of policy2 or procedural requirement 3 to the inclusive type which not only places an absolute prohibition on such legislation in certain named instances, but in all other 4 cases where a general law can be made applicable. An accurate classification of these provisions is not a sim- ple matter. Few are identical in wording. Some, though pat- ently at variance, appear to have received synonymous appli- cation. -

Ray O' Light Newsletter

RAY O’ LIGHT NEWSLETTER March-April 2018 No. 107 & May-June 2018 No. 108 DOUBLE ISSUE Publication of the Revolutionary Organization of Labor, USA The Current State of U.S. Society and of the U.S. Empire’s Government by RAY LIGHT The first quarter of 2018 has brought much political - Chaos among the Rulers- turbulence and disruption both to the rulers and the ruled in the USA. Because U.S. imperialism is still the Previously, we have discussed the contradiction between main bulwark of world capitalism, what has been going President Trump’s constant effort to defend the Trump on in the USA these days has real significance for the Family Empire and his relative indifference to the international proletariat and the oppressed peoples of interests of the Wall Street ruling class, i.e. the strategic the world, as well. interests of the U.S. Empire. The Trump Regime itself has included representatives of both the Trump Empire Fundamentally, what has been occurring in the USA and the U.S. Empire. This is reflected in the continual over these several months reflects the fact that the U.S. lurching of the Trump Regime from one crisis to the Empire continues its decline. next and the continued paralysis of the “Republicrat” (contd. on p. 5) A MAY DAY 2018 Greeting and Salute to the High School Youth Protesting Violence in Public Schools and Communities Across the USA — from RAY LIGHT and CINDY SHEEHAN — We are encouraged that tens of thousands of high the future of our country in their hands, are not safe school youth left their schools and took to the streets to from an epidemic of violence that is sweeping across protest the fact that, even in school, our youth, holding the USA. -

Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon Richard H

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Constitutional Commentary 2000 Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon Richard H. Pildes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Pildes, Richard H., "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon" (2000). Constitutional Commentary. 893. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/893 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Constitutional Commentary collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, ANTI-DEMOCRACY, AND THE CANON Richard H. Pi/des* Democracy is the Banquo's ghost of American constitution alism. Appearing evanescently in vague discussions of process based theories of judicial review, or in isolated First Amendment cases involving political speech, or in momentary Equal Protec tion forays into racial redistricting, democracy hovers insistently over the constitutional canon. Yet democracy itself has not been brought onto center stage. From the background, democracy's obligations press upon the canon's principal players-rights, equality, separation of powers, federalism. We endlessly debate which issues should be left to "democratic bodies" and which to judicial review, but with little concern for the prior question of how the law ought to structure the institutions and ground rules of democracy itself. In the conventional constitutional canon, democracy is nearly absent as a systematic focus of study in its own right. If campaign financing is addressed, it is in narrow First Amendment terms of whether "money is speech"-not as part of the broader inquiry necessarily at stake concerning the role of political parties, individual candidates, and "independ ent" ideological and economic groups in a healthy democracy. -

James U. Blacksher Attorney at Law Phone: 205-591-7238 P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, AL 35201 Fax: 866-845-4395 E-Mail: Jblacksher@Ns

James U. Blacksher P.O. Box 636 Attorney at Law Birmingham, AL 35201 Phone: 205-591-7238 Fax: 866-845-4395 E-mail: [email protected] Statement of James U. Blacksher The Subcommittee on Elections of the Committee on House Administration Field Hearing, Birmingham, AL, May 13, 2019 Voting Rights and Election Administration in Alabama My name is James Blacksher. Thank you for inviting me to testify. I am a white native of Alabama and have been practicing law in Alabama since 1971, engaged primarily in representing African Americans in civil rights and voting rights litigation. I argued – and lost – City of Mobile v. Bolden (1980) in the Supreme Court, but with the help of co-counsel we won on remand to the district court. I testified in Congressional hearings leading to enactment of the 1982 Voting Rights Amendments. Four years later the Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) cited and adopted the three-prong test proposed in my Hastings Law Review article for purposes of establishing a violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. With Edward Still and Larry Menefee, I represented plaintiffs in the Dillard v. Crenshaw County class action, which changed the method of electing members of over 180 local governments in Alabama. I have represented African Americans in litigation following redistricting of the Alabama House and Senate districts and Congressional districts in every decade since the 1980 census. Most recently, I represented the plaintiffs before the Supreme Court in Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama (2015), which held that many of the Alabama House and Senate districts were racially gerrymandered.