Ayyappan Saranam’:1 Masculinity and the Sabarimala Pilgrimage in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile, Pattern and Outcome of Shri Amaranth Ji Yatri Patients Attending Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, India During Holy Yatra of 2017

Open Access CRIMSON PUBLISHERS C Wings to the Research Biostatistics & Bioinformatics ISSN 2578-0247 Research Article Profile, Pattern and Outcome of Shri Amaranth Ji Yatri Patients attending Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, India during Holy Yatra of 2017 G H Yatoo1, Mubashar Mashqoor Mir2 and Mohammad Sarwar Mir3* 1Department of Hospital Administration, SKIMS, India 2Department of Dermatology, GMC, India 3Department of Hospital Administration, SKIMS, India *Corresponding author: Mohammad Sarwar Mir, Senior Resident, Department of Hospital Administration, SKIMS, Srinagar, India Submission: May 09, 2018; Published: May 16, 2018 Abstract Introduction: Located deep in the Himalayas, the cave of Amarnath is one of the holiest pilgrimage site for Hindus in general and Shiva followers which sometimes these prove fatal. in particular. It is regarded to be the abode of Lord Shiva. Because of high altitude, rough terrain, harsh weather, pilgrims are prone to many illnesses Objective: To study the profile, pattern and outcome, among Shri Amarnath Ji yatri patients attending SKIMS in year 2017. Methodology: A prospective study was carried out during the yatra period, all pilgrims of Shri Amarnath ji Yatra who were referred to SKIMS from July-August 2017 were studied and the patients were followed from admission till discharge. The profile, pattern and outcome of illness in Yatris attendingResults: Yatra in the year 2017 was compared with the results of year 2011 and 2015. Out of 97 patients received at SKIMS, 54(55.67%) were having minor ailments and were seen on OPD basis, 43(44.32%) were admitted. 32(74.41%) admitted were males at the time of arrival 14(32.5%) were Road traffic Accidents followed by 7 patients (16.27%) who were Acute Myocardial Infarction. -

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga

Orissa Review * October - 2004 The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga Pradeep Kumar Gan Shaktism, the cult of Mother Goddess and vast mass of Indian population, Goddess Durga Shakti, the female divinity in Indian religion gradually became the supreme object of 5 symbolises form, energy or manifestation of adoration among the followers of Shaktism. the human spirit in all its rich and exuberant Studies on various aspects of her character in variety. Shakti, in scientific terms energy or our mythology, religion, etc., grew in bulk and power, is the one without which no leaf can her visual representation is well depicted in stir in the world, no work can be done without our art and sculpture. It is interesting to note 1 it. The Goddess has been worshipped in India that the very origin of her such incarnation (as from prehistoric times, for strong evidence of Durga) is mainly due to her celestial mount a cult of the mother has been unearthed at the (vehicle or vahana) lion. This lion is usually pre-vedic civilization of the Indus valley. assorted with her in our literature, art sculpture, 2 According to John Marshall Shakti Cult in etc. But it is unfortunate that in our earlier works India was originated out of the Mother Goddess the lion could not get his rightful place as he and was closely associated with the cult of deserved. Siva. Saivism and Shaktism were the official In the Hindu Pantheon all the deities are religions of the Indus people who practised associated in mythology and art with an animal various facets of Tantra. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 25.05.2014 to 31.05.2014

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 25.05.2014 to 31.05.2014 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kizhakkethil veettil, 1068/14, U/s TK Vinod Chumathra, Kizhakkan 29/5/14, JFMC 1 Shihas Noushad Noushad 24 143,147,149, 308 Thiruvalla Krishnan SI Punnakunnam, muthoor 17.15 Thiruvalla IPC Thiruvalla Kuttapuzha Bhagavathyparampil 1068/14, U/s TK Vinod Kizhakkan 29/5/14, JFMC 2 Sunil Kumar Thankappan 34 veettil, Cheeran chira, 143,147,149, 308 Thiruvalla Krishnan SI muthoor 17.15 Thiruvalla Chethipuzha IPC Thiruvalla Puthanchira veettil, 1068/14, TK Vinod Kizhakkan 29/5/14, JFMC 3 Pratheesh Prasad 29 Vazhapally, 143,147,149, 308 Thiruvalla Krishnan SI muthoor 17.30 Thiruvalla Changanachery IPC Thiruvalla Vadakemalayil veettil, 2422/13, U/s V. Rajeev, 31/5/14, JFMC 4 Sreekumar Sreedharan 38 Kavunkal, Vallamkulam Kuttoor 449, Thiruvalla Inspector of 11.00 hrs Thiruvalla west, Eraviperoor 323,307,354, IPC Police Thiruvalla Painumkattil 1076/14, U/s TK Vinod 31/05/14, JFMC 5 Amal Kumar Biju Kumar 22 puthuparampil, Kottoor, Kaviyoor 294(b), Thiruvalla Krishnan SI 10.00 Thiruvalla Kaviyoor 323,326,34 IPC Thiruvalla Painumkattil 1076/14, U/s TK Vinod 31/05/14, JFMC 6 Bimal Kumar Biju Kumar 21 puthuparampil, Kottoor, Kaviyoor 294(b), Thiruvalla Krishnan SI 10.00 Thiruvalla Kaviyoor 323,326,34 -

Bhadrakali - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

בהאדראקאלי http://www.tripi.co.il/ShowItem.action?item=948 بهادراكالي http://ar.hotels.com/de1685423/%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84-%D9%83%D8%A 7%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%88-%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%AF-%D8 %A8%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A-%D8%A7% D9%84%D9%81%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%82-%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A8 Bhadrakali - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhadrakali Bhadrakali From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bhadrak ālī (Sanskrit: भकाली , Tamil: பரகாள, Telugu: wq, Malayalam: , Kannada: ಭದಾ, Kodava: Bhadrak ālī (Good Kali, Mahamaya Kali) ಭದಾ) (literally " Good Kali, ") [1] is a Hindu goddess popular in Southern India. She is one of the fierce forms of the Great Goddess (Devi) mentioned in the Devi Mahatmyam. Bhadrakali is the popular form of Devi worshipped in Kerala as Sri Bhadrakali and Kariam Kali Murti Devi. In Kerala she is seen as the auspicious and fortunate form of Kali who protects the good. It is believed that Bhadrak āli was a local deity that was assimilated into the mainstream Hinduism, particularly into Shaiva mythology. She is represented with three eyes, and four, twelve or eighteen hands. She carries a number of weapons, with flames flowing from her head, and a small tusk protruding from her mouth. Her worship is also associated with the Bhadrakali worshipped by the Trimurti – the male Tantric tradition of the Matrikas as well as the tradition of the Trinity in the North Indian Basohli style. -

Chapter 7, Verses 13 to 16,Taitreya Upanishad, Class 36,Baghawat Geeta, Class

Bhagawat Geeta, Class 105: Chapter 7, Verses 13 to 16 Shloka # 13: त्िरिभर्गुणमयैर्भावैरेिभः सर्विमदं जगत्। मोिहतं नािभजानाित मामेभ्यः परमव्ययम्।।7.13।। Due to three (kinds of) objects, consisting of (prakriti’s) constituents, this whole world is deluded; it fails to cognize Me, the immutable (Reality) beyond them. Continuing his teaching of the Gita, Swami Paramarthananda said, with the 12th shloka of chapter 7, Sri Krishna has completed talking about Ishwaraswarupam. In his talks, Sri Krishna points out that the entire universe is God himself consisting of the Spirit (consciousness) that is of a higher nature and Matter, consisting of an inferior nature. Wherever there is change it is Apara Prakriti (AP). So, the whole world, the body, mind and thought all are AP. The Para Prakriti (PP) is the consciousness alone, which is changeless and formless. Now, Sri Krishna discussed another topic, raising the question as to why do humans suffer when everything in the universe is divine? Why does one feel incomplete, insecure and not at ease? This is a universal problem. Different people solve it in different ways. Some acquire material things, some seek position, some seek power, name, family etc. Nothing, however, seems to work. This universal problem is called Samasra. Sri Krishna is diagnosing the problem in shloka # 13 and provides its resolution in shloka # 14. The problem is this: Since the Para prakriti (PP) is formless, colorless and not accessible for our perception, we generally miss it. Hence it is also called “Aprameya” meaning not accessible to perception. -

Get Set Go Travels Hotel Akshaya Building, Opp: DRM Office, Waltair Station Approach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530016

Get Set Go Travels Hotel Akshaya Building, Opp: DRM Office, Waltair Station Approach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530016. Phone: +91 92468 14399, +91 90004 18895 Mail: [email protected] Web: www.getsetgotravels.in The Pancharama Kshetras or the (Pancharamas) are five ancient Hindu temples of Lord Shiva situated in Andhra Pradesh. These Sivalingas are formed out of one single Sivalinga. As per the legend, this five Sivalingas were one which was owned by the Rakshasa King Tarakasura. None could win over him due to the power of this Sivalinga. In a war between deities and Tarakasura, Kumara Swamy and Tarakasura were face to face. Kumara Swamy used his Sakthi aayudha to kíll Taraka. By the power of Sakti aayudha the body of Taraka was torn into pieces. But to the astonishment of Lord Kumara Swamy all the pieces reunited to give rise to Taraka. Kumara Swamy repeatedly broke the body into pieces and it was re-unified again and again. This confused Lord Kumara Swamy and was in an embarrassed state then Lord Sriman-Narayana appeared before him and said “Kumara! Don’t get depressed, without breaking the Shiva lingham worn by the asura you can’t kíll him” you should first break the Shiva lingam into pieces, then only you can kíll Taraka Lord Vishnu also said that after breaking, the shiva lingha it will try to unite. To prevent the Linga from uniting, all the pieces should be fixed in the place where they are fallen by worshiping them and erecting temples on them. By taking the word of Lord Vishnu, Lord Kumara Swamy used his Aagneasthra (weapon of fire) to break the Shiva lingha worn by Taraka, Once the Shiva lingha broke into five pieces and was trying to unite by making Omkara nada (Chanting Om). -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Souvenir Lazer.Pmd

IDRBT AWARD Dr. Y.V. Reddy, RBI Governor Presents IDRBT Award. 100 per cent Core Banking Mr. N.R. Narayana Moorthy, Chief Mentor, Infosys Technologies declares SIB as 100 per cent CBS enabled 500th Branch Ms. Sheila Dikshit, Chief Minister of Delhi inaugurating 500th Branch Dear Patrons & Well Wishers, Someone once said “If you add a little to a little and do this often, soon the little will become great”. South Indian Bank as it ushers in its 80th year of service to the community is the very epitome of this quotation. From its humble beginnings in 1929, the bank has grown from strength to strength in delivering outstanding value to its customers and creating a name for itself in the banking arena. With an initial paid up capital of Rs 22000, the bank has now grown into an organization with a business of Rs 27000 crores, presence in 23 states and 520 branches, truly making it a force to reckon with amongst the banks in the country. “ ... little will become great ” The journey over the last 80 years has not been without its fair share of difficulties, but our bank has always endeavoured to ensure that the basic epithet of customer service was never compromised. Our achievements are a glowing testimonial of the confidence and the trust which we enjoy with our customers. We have been pioneers right from being the first private sector bank to open a NRI branch as well as being the first to start an Industrial Finance branch in 1993. We have been ahead of the curve in taking cognisance of the importance of technology and achieved 100% implementation of the Core Banking Solution in 2007. -

Lord Shiva in Varanasi Visual Processes and the Representation

OWE WIKSTRÖM Darsan (to See) Lord Shiva in Varanasi Visual Processes and the Representation of God by Seven Ricksha-Drivers Introduction In spite of its effort to be transculturally relevant, the psychology of relig- ion is quite ethno- or rather Western-centric. This becomes very clear when one tries to "translate" Indian folk religiosity into concepts taken from mainline theories; i.e. social, cognitive or psychoanalytical psychology of religion. Not only do the norms and values differ, but the very ontological assumptions underlying the categories in which the researcher understand differs fundamentally from the internal Hindu anthropological and epis- temiological apriori. For example, their words of the psyche include contex- tuality, from time to space, to ethics to groups. The subtle interrelatedness of the divine, spiritual and the mundane is obvious (Geertz 1973). It in- cludes the flows and exchanges of substances within and between persons with minimal outer bondaries. The psychological makeup of persons in societies so civilizationally dif- ferent as India is embedded in fundamentally distinct principles of these cultures and the social patterns and child rearing that these principles shape (Marsella et al 1985). Therefore it is clear that a western scholar and an Indian devotee are quite different, not only simply that they see things differently, coming from varied cultures, but that the very inner emotional- cognitive makeup is culturally constructed in different ways (Roland 1989). Of course this will "disturb" the interaction between interviewer and in- terviewee, the scholar and the pious man. In order to understand the psy- chological dynamics in folk religiosity, I think that the researcher has to re- examine and be aware of the way he uses the theoretical models in cross- cultural psychological hermeneutics. -

Bread Review 2007-08.Cdr

earc es h, E R d ic u s c a a t B i o n A B R E A D n d y t D e e i v c e o l S o t p m n e BREAD REVIEW 2007-08 BASIC RESEARCH, EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT (BREAD) SOCIETY earc es h, E R d ic u s c a a t B i o n A B R E A D n d y t D e e i v c BREAD REVIEW 2007-08 e o l S o t p m n e FROM THE SECRETARY'S DESK Dear Sir / Madam, BREAD Society's mission is to provide financial assistance to bright indigent students to pursue higher education till they attain their maximum potential while simultaneously inculcating good values among them. It also administers the donors' funds efficiently passing on every rupee of the donation to the scholar. BREAD Society has adopted its present methodology to identify the bright underprivileged students in 2003-04. Our experience over the past five years has made us refine our systems to ensure that we reach out to the most deserving students even in the most remote areas of the state. Our latest initiative in this regard is to try to get the BREAD Poster displayed in the Notice Boards of all the 1450 government and government aided institutions of higher education in Andhra Pradesh by mailing A-4 size colour posters to all the Principals. The abundant human resource wealth lying dormant, mostly in the remote rural areas of the countryside, can be unearthed to create a real knowledge based society at a nominal cost. -

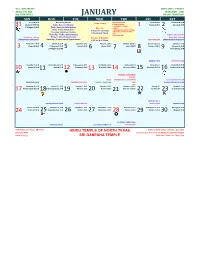

Temple Calendar

Year : SHAARVARI MARGASIRA - PUSHYA Ayana: UTTARA MARGAZHI - THAI Rtu: HEMANTHA JANUARY DHANU - MAKARAM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Tritiya 8.54 D Recurring Events Special Events Tritiya 9.40 N Chaturthi 8.52 N Temple Hours Chaturthi 6.55 ND Daily: Ganesha Homam 01 NEW YEAR DAY Pushya 8.45 D Aslesha 8.47 D 31 12 HANUMAN JAYANTHI 1 2 P Phalguni 1.48 D Daily: Ganesha Abhishekam Mon - Fri 13 BHOGI Daily: Shiva Abhishekam 14 MAKARA SANKRANTHI/PONGAL 9:30 am to 12:30 pm Tuesday: Hanuman Chalisa 14 MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm PUJA Thursday : Vishnu Sahasranama 28 THAI POOSAM VENKATESWARA PUJA Friday: Lalitha Sahasranama Moon Rise 9.14 pm Sat, Sun & Holidays Moon Rise 9.13 pm Saturday: Venkateswara Suprabhatam SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI 8:30 am to 8:30 pm NEW YEAR DAY SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI Panchami 7.44 N Shashti 6.17 N Saptami 4.34 D Ashtami 2.36 D Navami 12.28 D Dasami 10.10 D Ekadasi 7.47 D Magha 8.26 D P Phalguni 7.47 D Hasta 5.39 N Chitra 4.16 N Swati 2.42 N Vishaka 1.02 N Dwadasi 5.23 N 3 4 U Phalguni 6.50 ND 5 6 7 8 9 Anuradha 11.19 N EKADASI PUJA AYYAPPAN PUJA Trayodasi 3.02 N Chaturdasi 12.52 N Amavasya 11.00 N Prathama 9.31 N Dwitiya 8.35 N Tritiya 8.15 N Chaturthi 8.38 N 10 Jyeshta 9.39 N 11 Mula 8.07 N 12 P Ashada 6.51 N 13 U Ashada 5.58 D 14 Shravana 5.34 D 15 Dhanishta 5.47 D 16 Satabhisha 6.39 N MAKARA SANKRANTHI PONGAL BHOGI MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN SRINIVASA KALYANAM PRADOSHA PUJA HANUMAN JAYANTHI PUSHYA / MAKARAM PUJA SHUKLA CHATURTHI PUJA THAI Panchami 9.44 N Shashti 11.29 N Saptami 1.45 N Ashtami 4.20 N Navami 6.59