And Burying Beetles (Nicrophorus Spp): Differences Between Northern and Southern Temperate Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolutionary Significance of Body Size in Burying Beetles

Brigham Young University Masthead Logo BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2018-04-01 The volutE ionary Significance of Body Size in Burying Beetles Ashlee Nichole Momcilovich Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Momcilovich, Ashlee Nichole, "The vE olutionary Significance of Body Size in Burying Beetles" (2018). All Theses and Dissertations. 7327. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7327 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Evolutionary Significance of Body Size in Burying Beetles Ashlee Nichole Momcilovich A dissertation submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Mark C. Belk, Chair Seth M. Bybee Jerald B. Johnson Steven L. Peck G. Bruce Schaalje Department of Biology Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Ashlee Nichole Momcilovich All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Evolutionary Significance of Body Size in Burying Beetles Ashlee Nichole Momcilovich Department of Biology, BYU Doctor of Philosophy Body size is one of the most commonly studied traits of an organism, which is largely due to its direct correlation with fitness, life history strategy, and physiology of the organism. Patterns of body size distribution are also often studied. The distribution of body size within species is looked at for suggestions of differential mating strategies or niche variation among ontogenetic development. Patterns are also examined among species to determine the effects of competition, environmental factors, and phylogenetic inertia. -

A Beautiful Insect That Buries Dead Bodies Is in the Middle of a Conservation Battle

We use cookies to provide you with a better onsite experience. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy. SUBSCRIBE CONSERVATION A Beautiful Insect That Buries Dead Bodies Is In the Middle of a Conservation Battle Oil companies want the American burying beetle to be the first recovered insect taken off the U.S. endangered species list. But scientists say comeback claims are wildly exaggerated By Hannah Nordhaus | Scientific American December 2017 Issue Credit: Joel Sartore Getty Images ADVERTISEMENT IN BRIEF On the federal endangered species list since 1989, the American burying beetle needs small animal carcasses to live. Beetle habitat overlaps with oil and gas industry operations, and the industry wants the insect off the protected list. Arguments turn on whether the beetle's current population is robust enough to survive in a habitat that includes more pipelines, drilling rigs and roads. The beetle ranch is lovely: slate tile, a Viking range, knotty oak paneling and a wood stove with a preening taxidermy turkey on the wall above it. The porch is lined with rocking chairs that face out to a massive walnut tree and, beyond it, the pastures and thickets of southern Oklahoma's Lower Canadian Hills. Clover fields glow in the afternoon sun. A phoebe hollers from her nest; a scissortail flits between fence and field. People working at the ranch carry all sorts of weapons. Amy Smith, a biologist who conducts research here, keeps a .38 handgun strapped to her waist. Preston Smith, an owner of the property (and no relation to Amy Smith), is a six-and-a-half-foot-tall Texan who wears a beautiful silver-and-black combination .45 and .410 revolver engraved with his name. -

American Burying Beetle

American Burying Beetle U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 9014 East 21st Street Tulsa, Oklahoma 74129 Nicrophorus americanus - Olivier 918- 5 8 1 - 7458 6 / 4 / 2 0 1 4 Available online http://www.fws.gov/southwest/es/Oklahoma/ABB_Add_Info.htm American Burying Beetle (ABB) Nicrophorus americanus Executive Summary The American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus, ABB) is the largest silphid (carrion beetle) in North America, reaching 1.0 to 1.8 inches (2.5-4.5 cm) in length (Wilson 1971, Anderson 1982, Backlund and Marrone 1997). The most diagnostic feature of the ABB is the large orange-red marking on the raised portion of the pronotum (hard back plate of the front portion of the thorax of insects), a feature shared with no other members of the genus in North America (USFWS 1991). The ABB is a nocturnal species that lives only for one year. The beetles are active in the summer months and bury themselves in the soil for the duration of the winter. Immature beetles (tenerals) emerge in late summer, over-winter as adults, and comprise the breeding population the following summer (Kozol 1990a). Adults and larvae are dependent on carrion (animal carcass) for food and reproduction. They must compete for carrion with other invertebrate and vertebrate species. Having wings, ABBs are strong fliers and have been reported moving distances ranging from 0.10 to 18.14 miles (0-29.19 kilometers) in various parts of their range (Bedick et al. 1999, Creighton and Schnell 1998, Jurzenski 2012, Jurzenski et al. 2011, Schnell et al. 1997-2006). In Oklahoma, ABBs have been recorded to move up to 10 km (6.2 miles) in 6 nights (Creighton and Schnell 1998). -

Vol.29 NO.L SOUTHWESTERNENTOMOLOGIST MAR.2004

vol.29 NO.l SOUTHWESTERNENTOMOLOGIST MAR.2004 GENETIC VARIATION AND GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE SUBTERRANEAN TERMITE GENUS RETICULITERMESItN Tpx.q,S JamesW. Austin2,Allen L. Szalanski2,Roger E. Gold3,and Bart T. Fost# ABSTRACT A molecular geneticsstudy involving DNA sequencingof a portion of the mitochondrialDNA 165 genewas undertakento determinethe extent of geneticvariation with Reticulitermesspp. and the distribution of Reticulitermesspp. subterraneantermites in Texas.From 42 Texascounties a total of 68 R. flavipes, sevenR. hageni,eight R. virginicus,and nine R. tibialis were identified. No geneticvariation was observedin R. virginicus andR. hageni,while sevenhaplotypes were observedin R. tibialis and 13 for R. flavipes.Among the 13.R.flavipes haplotypes,9nucleotides were variableand genetic variationranged from 0.2 to l.60/o.Phylogenetic analysis did not revealany relationships amongthe R. tibialis arld R. flavipes haplotypes,and there wasino apparentgeographical structureto the haplotypes.The high amount of genetic variation, but a lack of genetic structure in R. flavipes supports the hypothesis that this termite species has been distributedrandomly by mandue to its associationwith structures. INTRODUCTION The most abundant native termite in Texas is the subterranean genus ReticulitermesHolgren (Rhiniotermitidae).Four species, the eastern subtenanean Reliculitermesflavipes (Kollar), light southemR. hageniBanks, arid n. nDialis Banks,and dark southernR. virginicus (Banks),are known to occur in Texas(Howell et al. 1987). These speciesare among the most destructiveand costly termites for homeownersand businessesalike, and are of considerableeconomic importance. Su (1993)estimated that over $ I .5 billion is spentannually for termite control in the U.S., of which 80olois spentto control subterraneantermites, More recent estimatesby the National Pest Management Associationsuggest the cost to exceed$2.5 billion annually(Anonymous 2003). -

The American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus Americanus) Population at Camp Gruber, Ok Breeding and Overwintering Survival

THE AMERICAN BURYING BEETLE (NICROPHORUS AMERICANUS) POPULATION AT CAMP GRUBER, OK BREEDING AND OVERWINTERING SURVIVAL By LEONARDO VIEIRA SANTOS Bachelor of Science in Agronomic Engineering Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Botucatu, São Paulo 2018 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 2020 THE AMERICAN BURYING BEETLE (NICROPHORUS AMERICANUS) POPULATION AT CAMP GRUBER, OK BREEDING AND OVERWINTERING SURVIVAL Thesis Approved: Dr. W. Wyatt Hoback Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristopher Giles Dr. Craig Davis ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the U.S. Army National Guard, the Cherokee Nation and the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology for funding this research. The research I conducted would not have been possible if not for the help of several people. Dr. Wyatt Hoback, thank you for giving me the chance to work with the amazing American Burying Beetle, your knowledge, patience and guidance made it possible for me to have amazing experiences to conduct my research and become a better researcher. A special thanks goes to my other two committee members, Dr. Craig Davis and Dr. Kristopher Giles, for all the valuable insights and guidance throughout the project. None of this research would have been possible without the help of those in the field with me. Many thanks to Alexander Harman, Mason Taylor, Melissa Reed, Thomas Hess and Sandra Rigsby for helping me during these two year with collection of data in the field. Thanks to Pat Gwin, from the Cherokee Nation, for the assistance both in the field and with logistics. -

Effects of Humidity and Temperature On

EFFECTS OF HUMIDITY AND TEMPERATURE ON BURYING BEETLE (COLEOPTERA: SILPHIDAE) SURVIVAL AND FLIGHT By DAN ST. AUBIN Bachelor of Science in Entomology and Plant Pathology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2017 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 2017 EFFECTS OF HUMIDITY AND TEMPERATURE ON BURYING BEETLE (COLEOPTERA: SILPHIDAE) SURVIVAL AND FLIGHT Thesis Approved: Dr. W. Wyatt Hoback - Thesis Adviser Dr. Kris Giles Dr. George Opit Dr. Amy Smith ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first and foremost, like to thank those who worked most closely with me to simply “complete my thesis.” A great deal of help came from Marcela Gigliotti, for helping me run my beetles and helping me omit long and drab narratives. For allowing us to collect and sample beetles out at Camp Gruber, I thank Rusty and Larry for setting us up with great sampling locations and support. Gratitude also goes out to everyone whom I’ve interacted with on the base at camp Gruber. Thanks goes out to my field crews who helped me to gather data and work in the field; Lexi Freeman and Jacob Farreister. I would like to thank the programs that contributed grants, research funding, and scholarships. When times were tough, my parents were always there supporting me financially and spiritually; thanks Mom and Dad. I owe you both more than I could pay back. I’m grateful to have seen all the live musicians I’ve seen over my years at OSU and my road crews for sharing the miles to and from. -

American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus Americanus )

American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus ) A Species Conservation Assessment for The Nebraska Natural Legacy Project Prepared by Melissa J. Panella Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Wildlife Division March 2013 The mission of the Nebraska Natural Legacy Project is to implement a blueprint for conserving Nebraska’s flora, fauna, and natural habitats through the proactive, voluntary conservation actions of partners, communities and individuals. Purpose The primary goal in development of at-risk species conservation assessments is to compile biological and ecological information that may assist conservation practitioners in making decisions regarding the conservation of species of interest. The Nebraska Natural Legacy Project recognizes the American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus ) as a Tier I at-risk species of high conservation priority. Indeed, the American Burying Beetle (ABB) is a species of conservation need throughout its range. Here, I provide some general management recommendations regarding ABB; however, conservation practitioners will need to use professional judgment for specific management decisions based on objectives, location, and site-specific conditions. This resource provides available knowledge of ABB that may aid in the decision-making process or in identifying research needs for the benefit of the species. Species conservation assessments will be updated as new scientific information becomes available. The Nebraska Natural Legacy Project focuses efforts in the state’s Biologically Unique Landscapes (BULs), -

Abstract Volume

th German Zoological Society 105 Annual Meeting Abstract Volume September 21 – 24, 2012 University of Konstanz, Germany Sponsored by: Dear Friends of the Zoological Sciences! Welcome to Konstanz, to the 105 th annual meeting of the German Zoological Society (Deutsche ZoologischeGesellschaft, DZG) – it is a great pleasure and an honor to have you here as our guests! We are delighted to have presentations of the best and most recent research in Zoology from Germany. The emphasis this year is on evolutionary biology and neurobiology, reflecting the research foci the host laboratories from the University of Konstanz, but, as every year, all Fachgruppen of our society are represented – and this promisesto be a lively, diverse and interesting conference. You will recognize the standard schedule of our yearly DZG meetings: invited talks by the Fachgruppen, oral presentations organized by the Fachgruppen, keynote speakers for all to be inspired by, and plenty of time and space to meet and discuss in front of posters. This year we were able to attract a particularly large number of keynote speakers from all over the world. Furthermore, we have added something new to the DZG meeting: timely symposia about genomics, olfaction, and about Daphnia as a model in ecology and evolution. In addition, a symposium entirely organized by the PhD-Students of our International Max Planck Research School “Organismal Biology” complements the program. We hope that you will have a chance to take advantage of the touristic offerings of beautiful Konstanz and the Bodensee. The lake is clean and in most places it is easily accessed for a swim, so don’t forget to bring your swim suits.A record turnout of almost 600 participants who have registered for this year’s DZG meeting is a testament to the attractiveness of Konstanz for both scientific and touristic reasons. -

Burying Beetles

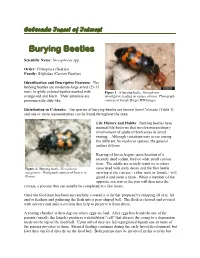

Colorado Insect of Interest Burying Beetles Scientific Name: Nicrophorus spp. Order: Coleoptera (Beetles) Family: Silphidae (Carrion Beetles) Identification and Descriptive Features: The burying beetles are moderate-large sized (25-35 mm), brightly colored beetles marked with Figure 1. A burying beetle, Nicrophorus orange-red and black. Their antennae are investigaror, feeding on a piece of meat. Photograph pronouncedly club-like. courtesy of Joseph Berger/IPM Images Distribution in Colorado: Ten species of burying beetles are known from Colorado (Table 1) and one or more representatives can be found throughout the state. Life History and Habits: Burying beetles have unusual life histories that involve extraordinary involvement of adults of both sexes in larval rearing. Although variations may occur among the different Nicrophorus species, the general outline follows. Rearing of larvae begins upon location of a recently dead rodent, bird or other small carrion item. The adults are acutely sensitive to odors Figure 2. Burying beetle, Nicrophorus associated with early decay and the first beetle marginatus. Photograph courtesy of Insects in arriving at the carcass - either male or female - will Kansas. guard it and await a mate. When a member of the opposite sex arrives the pair will then inter the carcass, a process that can usually be completed in a few hours. Once the food item has been successfully covered it is further prepared by stripping all skin, fur and/or feathers and gathering the flesh into a pear-shaped ball. The flesh is chewed and covered with salivary and anal secretions that help to preserve it from decay. A rearing chamber is then dug out where eggs are laid. -

Burying Beetle Baited Trap Advanced Activity!!!

Burying Beetle Baited Trap Advanced Activity!!! Use the same pitall trap, but add a bait to trap for burying and carrion beetles. ñ The American burying beetle, like all burying and carrion beetles, use dead animals for their repro- ducton and food source. ñ Using a bait that imitates the smell of dead animal can atract them to your trap! ñ Be sure to NOT add soapy water to your cups this tme, in case of collectng American burying beetles (remember, they are protected under the Endangered Species Act!) What you need: ñ Two solo cups or similar sized cups (yogurt cup, etc) ñ A shovel ñ Styrofoam plate This can be added in a smaller cup ñ Chopstcks or a baggie with holes in it, and ñ Danny King’s Catish placed inside your pitall cups Punch Bait (available at Walmart) ABB are in OK! Please be aware of your locaton and the possibly of catching American burying beetles. If you are in any of the eastern, blue countes of Oklahoma shown below, please use your pitall trap with cauton! Check them frequently, so as not to let the beetles trapped for too long. Oklahoma’s Brightest Orange! ABB Anatomy Elytra (wing coverings) Pronotum Clubbed antennae Mouthparts Legs Compound eye Abdomen Thorax Head Look Closely! The American burying beetle has distnctve or- ange markings on its head, pronotum and elytra. But, don’t be fooled! Other species have similar markings. ñ Can you tell the diference between these two? ñ Which one is the American burying beetle? Nicrophorus americanus Common Burying & Carrion Beetle Identification: Nicrophorus marginatus Nicrophorus carolinus “Marg” have bright orange bands that connect on “Carols” have small orange markings, the botom two their sides. -

NDOR American Burying Beetle Research Final Report

NDOR American Burying Beetle Research Final Report W. Wyatt Hoback, University of Nebraska at Kearney Introduction The American burying beetle, (Nicrophorus americanus) is a member of the carrion beetle family Silphidae, an important group of detritivores that recycle decaying materials into the ecosystem. The American burying beetle is the largest carrion-feeding insect in North America reaching a length of about 4 centimeters and a weight of 3 grams. Although it has historically been recorded from at least 150 counties in 35 states in the eastern and central United States, it declined from the 1920s to the 1960s and is currently only found at the peripheries of its former range. In 1983 the American burying beetle was included as an endangered species in the Invertebrate Red Book published by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. In the United States, it was placed on the state and federal endangered species lists in August, 1989. Considering the broad geographic range formerly occupied by the American burying beetle, it is unlikely that vegetation or soil type were historically limiting. Habitats in Nebraska where these beetles have been recently found consist of grassland prairie, forest edge and scrubland. Unlike other members of the Nicrophorus genus, no strong correlation with soil type or land use seems to exist (Bishop et al. 2002; Bishop and Hoback unpublished), however, adequate soil moisture levels appear critical (Hoback et al. unpublished). Within its remaining range in Nebraska, there is a large population (>500 individuals) in the southern loess hills and another significantly larger population in northern Nebraska and southern South Dakota (Hoback and Snethen unpublished). -

This Work Is Licensed Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. SOIL ZOOLOGY, THEN AND NOW - MOSTLY THEN D. Keith McE. Kevan Department of Entomology and Lyman Entomological Museum and Research Laboratory Macdonald College Campus, McGill University 21, 111 Lakeshore Road Ste-Anne de Bellevue, Que. H9X ICO CANADA Quaestiones Entomologicae 21:371.7-472 1985 ABSTRACT Knowledge of the animals that inhabit soil remained fragmentary and virtually restricted to a few conspicuous species until the latter part of the 19th Century, despite the publication, in 1549, of the first attempt at a thesis on the subject by Georg Bauer (Agricola). Even the writings of far-seeing naturalists, like White in 1789, and Darwin in 1840, did not arouse interest in the field. It was probably P.E. Midler in 1879, who first drew particular attention to the importance of invertebrate animals generally in humus formation. Darwin's book on earthworms, and the "formation of vegetable mould", published in 1881, and Drummond's suggestions, in 1887, regarding an analgous role for termites were landmarks, but, with the exception of a few workers, like Berlese and Diem at the turn of the century, little attention was paid to other animals in the soil, save incidentally to other investigations. Russell's famous Soil Conditions and Plant Growth could say little about the soil fauna other than earthworms.