Torresnarvaez-Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Minds Morgan and Garcia Hook up Pourrez En Quelques Cliques Trouver La Perle Rare

Apr 20, · Penelope Garcia (Kirsten Vangsness) and Derek Morgan (Shemar Moore) were the lighthearted dynamic duo of the BAU on Criminal Minds. Their relationship was . Derek Morgan is a former Supervisory Special Agent with the FBI's Behavioral Analysis Unit. For a time, he was the acting unit chief of the BAU, taking over as Hotch stepped down temporally. Morgan specialized in explosives, fixations, and obsessive behaviors. He officially resigned from the BAU in Season Eleven in order to be with his new family. His position was taken over by Luke Alvez in. Jan 15, · Directed by Tawnia McKiernan. With Joe Mantegna, Shemar Moore, Matthew Gray Gubler, A.J. Cook. When a murder investigation opens in San Jose, Garcia is forced to delve into her past as a hacker and reconnect with her former boyfriend to help the BAU solve the case. Feb 10, · Yes, former Superman Dean Cain starred in the latest Criminal Minds as a gambling addict/murderer. It was good to see him. But there was a rewind & repeat moment that I need to talk about more. It has to do with a certain scene that featured Morgan and Garcia. You know the one. Garcia was nursing quite the hangover. J.J. called to tell her they. May 28, · Sometimes we get inside a show so much that we forget that the actors are real people with a different life than the one we see on screens. ‘Criminal Minds’ has been on the air for more than thirteen years, and you’d be surprised by the real-life spouses of the main cast. -

Tax Time Sale NOW in PROGRESS

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Horoscopes ........................................................... 2 Now Streaming ...................................................... 2 Puzzles ................................................................... 4 TV Schedules ......................................................... 5 “The Hunt” seeks “Mrs. America” Traveling and Top 10 ................................................................... 6 6 out savage satire 7 starts a movement 7 eating out by proxy Home Video .......................................................... 7 April 11 - April 17, 2020 Peacock shows its feathers as streaming service premieres BY JAY BOBBIN and “Parenthood” also among series choices. The “Battlestar Galactica”: Executive producer Sam Its debut date was set before people likely started Universal movie library will provide a wide range of Esmail’s (“Mr. Robot”) take on the sci-fi saga pits doing their viewing at home more than ever, and a selections, with “E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial,” “Jurassic humans against evil Cylons again. new streaming service is about to become another Park” and “Schindler’s List” (all directed by Steven “Brave New World”: The classic Aldous Huxley option for them. Spielberg, as it happens) as several of the available novel gets a new treatment starring Alden Ehrenreich NBC Universal launches its direct-to-consumer titles. (“Solo: A Star Wars Story”), Demi Moore and Jessica Peacock – named in tribute to the NBC network’s Different takes on current TV offerings will be on Brown Findlay. the Peacock menu, too, with viewers able to watch classic logo – in the first of two waves Wednesday, “Division One”: Besides “Parks and Recreation,” “The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon” and “Late April 15. The customer base of NBC Universal parent Amy Poehler supplies something new to Peacock as Comcast gets it first, then the service will go wide on Night With Seth Meyers” several hours earlier. -

TV Technoculture: the Representation of Technology in Digital Age Television Narratives Valerie Puiattiy

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 TV Technoculture: The Representation of Technology in Digital Age Television Narratives Valerie Puiattiy Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES TV TECHNOCULTURE: THE REPRESENTATION OF TECHNOLOGY IN DIGITAL AGE TELEVISION NARRATIVES By VALERIE PUIATTI A Dissertation submitted to the Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 Valerie Puiatti defended this dissertation on February 3, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Leigh H. Edwards Professor Directing Dissertation Kathleen M. Erndl University Representative Jennifer Proffitt Committee Member Kathleen Yancey Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Laura and Allen, my husband, Sandro, and to our son, Emilio. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without the support of many people. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Leigh H. Edwards, for her encouragement and for the thoughtful comments she provided on my chapter drafts. I would also like to thank the other committee members, Kathleen M. Erndl, Jennifer Proffitt, and Kathleen Yancey, for their participation and feedback. To the many friends who were truly supportive throughout this process, I cannot begin to say thank you enough. This dissertation would not have been written if not for Katheryn Wright and Erika Johnson-Lewis, who helped me realize on the way to New Orleans together for the PCA Conference that my presentation paper should be my dissertation topic. -

E-Score Celebrity Special Report Data Through Third Quarter 2009

E-Score Celebrity Special Report Data through Third Quarter 2009 Prepared for: E-Score Celebrity Clients www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY E-POLL Market Research Table of Contents E-Score Celebrity Methodology……………………………………………….….……..3 Celebrities with Highest Appeal By Age Group………...……………………………..….4 Celebrities with Biggest Gains and Declines in Appeal…………………………………..7 Up & Comers – Low Awareness, High Appeal, and Talented.………….………………..10 Blockbuster Movie Actor/Actress Gains and Declines By Age Group.…………………....12 Most Appealing Reality TV Show Host By Age Group……………………...……………..14 About E-Score Celebrity & E-Poll Market Research …………..……………………...….17 Contact Information………………………………………………………………...…..20 2 www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY EPOLL Market Research E-Score Celebrity: Methodology The E-Score Celebrity database includes more than 4,800 celebrities, athletes, and newsmakers Methodology • E-Poll panel members receive survey invitations via email • Respondents age 13+, total completed surveys per wave = 1,100 • Stratified sample - representative of the general population by age, gender, region • Unique sample, fielded on a weekly basis • Length of survey limited to 25 names • Name only / Image only evaluation of awareness • Six point appeal scale • More than 40 attributes + open ends Please Note: Throughout this report… • Only celebrities with at least 16% awareness are referenced, except in the case of the “Up and Comers” list which includes celebrities with awareness between 6% and 15% and the “Blockbuster Movie Actor/Actress -

THIS JUST in Veggie Techie January/February

THIS JUST IN NATURAL Rx PROBLEM: Osteoarthritis SOLUTION: White willow bark THE SCOOP: If osteoarthritis is thwarting your pledge to get active in the New Year, white willow bark (Salix alba) can help renew your resolve. Containing a potent analgesic called salicin—a chemical similar to the pain-fighting ingredient in aspirin—white willow bark has been shown to offer relief from the aching stiffness of osteoar- thritis. A study in Phytotherapy Research found that OA patients techie taking an extract of the woody veggie bark experienced less pain and LYNDSAY BYRNES [Q&A] better movement in their joints. While white willow bark can Six seasons into the run Q How did you get the role on Criminal Minds? take longer to kick in than of CBS’s Criminal Minds, A The part was originally written for a guy and cast aspirin, the relief may last Kirsten Vangsness with a guy, but they realized the show was too guy- longer, and it doesn’t cause the will also appear as her heavy. It started as a two-line part; they wrote the stomach problems associated character—FBI technical character back into the show, and it turned into with high doses of aspirin. analyst (hacker) a regular role. I’m a theater girl—I can do something Penelope Garcia—in in one take and I can work really fast—and I write WHAT TO LOOK FOR the midseason spin-off too. The evolution of the character has been a lot Laurie Steelsmith, ND, LAc, Criminal Minds: Suspect my doing. author of Natural Choices for Behavior. -

Press Release: (Pdf Format)

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Robert Cable, Stanford Live 650-736-0091; [email protected] PHOTOS: http://live.stanford.edu/press NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO’S SELECTED SHORTS RETURNS TO BING WITH HOLIDAY STORIES ON DECEMBER 10 Host Kirsten Vangsness leads cast members Tate Donovan and Christina Pickles Stanford, CA, November 16, 2017—It’s story time for adults with National Public Radio’s award- winning series of short fiction read by the stars of stage and screen. Last seen at Stanford Live in 2015, the popular program Selected Shorts—which features classic and new works of short fiction for a live audience and to 300,000 radio listeners across the country every week—returns with a holiday-themed program for Bing Concert Hall stage on Sunday, December 10 at 2:30 p.m. Actress Kirsten Vangsness (Criminal Minds) leads cast members Tate Donovan (The Man in the High Castle) and Christina Pickles (Friends, Break a Hip), who will perform tales about returning home, running away, uninvited guests and unexpected gifts. The program will include stories by Laurie Notaro, Jeanette Winterson and Kurt Vonnegut. Selected Shorts is broadcast on more than 150 stations around the country. The radio show is recorded live as a popular New York City stage show that began in 1985 and still enjoys sellout audiences today. Also, the Selected Shorts podcast is one of the most popular podcasts on iTunes, with over 100,000 downloads every week. For more information, visit www.selectedshorts.org. TICKET INFORMATION Tickets for Selected Shorts on December 10 range from $30-$50 for adults and $15 for all Stanford students. -

Hollywood Extravaganza Auction VI

Welcome to Hollywood Live Auction’s Holiday Extravaganza Live Auction event weekend. We have assembled an incredible collection of rare iconic movie props and costumes featuring items from fi lm, television and music icons including John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Christopher Reeve, Michael Jackson, Don HollywoodJohnson and Kirk Douglas. Extravaganza Auction VI From John Wayne’s Pittsburgh costume, Michael Jackson’s deed and signed check to Th e Neverland Ranch, signed Billie Jean lyrics and signed, stage worn Fedora from the HIStory Tour, James Brown’s stage worn jumpsuit, Marilyn Monroe’sDay 2 gold high heels, Christopher Reeve’s Superman costume, Steve McQueen’s Enemy of the People costume, Robert Redford’s Th e Natural costume, Kirk Douglas’ Top Secret Aff air costume, Johnny Depp’s Blow costume, Don Johnson and Philip Michael Th omas’ Miami Vice costumes, and many more! Also from the new Immortals starring Mickey Rourke, bring home some of the most detailed costumes and props from the fi lm! If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy Hollywood Live Auctions’ Holiday Extravaganza event and we look forward to seeing you on March 24th – 25th for Hollywood Live Auctions’ Auction Extravaganza V. Special thanks to everyone at Premiere Props for their continued dedication in producing these great events. Have fun and enjoy the weekend! Sincerely, Dan Levin Executive VP Marketing CALL TO BID @ 1-888-761-PROP (7767) 109 Lot 502. -

E-Score Celebrity Quarterly Report Data Through First Quarter 2009

E-Score Celebrity Quarterly Report Data through First Quarter 2009 Prepared for: E-Score Celebrity Clients www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY EPOLL Market Research www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY EPOLL 1 Market Research Table of Contents E-Score Celebrity Methodology……………………………………………….….……3 Celebrities with Highest & Lowest Appeal..……………………………………………4 Celebrities with Biggest Gains and Declines in Appeal………………………………...8 Most Appealing Celebrities Among 18-49 Year Olds……………………………….....11 Celebrity Up & Comers……………………………………………………………….15 Most Appealing Television Hosts……………………………………………………..18 Most Appealing Celebrity Spokespersons…………………………………………….21 Most Appealing Athletes……………………………………………………………..24 Celebrities with Highest Attribute Scores.…………………………………………....27 (Overexposed, Trustworthy, Glamorous, Funny) Attributes by Generation……………………………………………………………..32 (Influential, Can Identify With) Highest Appeal Among African-Americans and Hispanics……………………………35 About E-Score Celebrity & E-Poll Market Research ………… ………………………38 Contact Information………………………………………………………………….41 www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY EPOLL 2 Market Research E-Score Celebrity: Methodology The E-Score Celebrity database includes more than 4,600 celebrities, athletes, and newsmakers Methodology • E-Poll panel members receive survey invitations via email • Respondents age 13+, total completed surveys per wave = 1,100 • Stratified sample - representative of the general population by age, gender, region • Unique sample, fielded on a weekly basis • Length of survey limited -

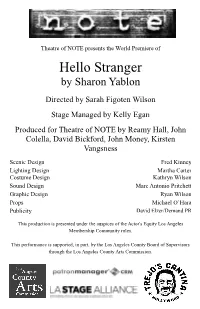

Hello Stranger by Sharon Yablon

Theatre of NOTE presents the World Premiere of Hello Stranger by Sharon Yablon Directed by Sarah Figoten Wilson Stage Managed by Kelly Egan Produced for Theatre of NOTE by Reamy Hall, John Colella, David Bickford, John Money, Kirsten Vangsness Scenic Design Fred Kinney Lighting Design Martha Carter Costume Design Kathryn Wilson Sound Design Marc Antonio Pritchett Graphic Design Ryan Wilson Props Michael O’Hara Publicity David Elzer/Demand PR This production is presented under the auspices of the Actor's Equity Los Angeles Membership Community rules. This performance is supported, in part, by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. Cast MIKE................................................................Trevor H Olsen*+ AUDREY...............................................................Aliyah Conley Oct 14, 20, 21, 28, 29; Nov 2, 3, 5 (4pm), 11, and 17 Maren O’Sullivan Oct 13, 19, 22, 27; Nov 4, 5 (7pm), 10, 12, and 18 CARLA...................................................................Reamy Hall*+ MANDY....................................................................Elinor Gunn CARPY........................................................Christopher Neiman+ JESUS.............................................................Alexis DeLaRosa+ Alternate Cast MIKE................................................................Jonathon Lamer*+ CARLA.............................................Nicole Gabriella Scipione*+ MANDY..............................................................Jennifer -

Family Matters

COVER STORY..............................................................2 The Sentinel FEATURE STORY...........................................................3 SPORTS.....................................................................4 MOVIES............................................................8 - 22 WORD SEARCH/ LATE LAUGHS/ CABLE GUIDE....................10 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS..................................................12 SUDOKU..................................................................13 tvweek STARS ON SCREEN/Q&A..............................................23 January 29 - February 4, 2017 Family Milo Ventimiglia and Mandy matters Moore star in “This Is Us” Ewing Brothers 2 x 3 ad www.Since1853.com Averaging more than nine million viewers per episode, “This Is Us” is barreling through its freshman season, having secured a full-season order just hours after its premiere. Starring Milo Ventimiglia (“Gilmore Girls”) and 630 South Hanover Street Mandy Moore (“A Walk to Remember,” 2002) among its ensemble cast, the series jaunts back and forth between Carlisle•7 17-2 4 3-2421 different time periods as it follows several characters whose lives are intertwined. An episode of “This Is Us” airs Tuesday, Jan. 31, on NBC. Steven A. Ewing, FD, Supervisor, Owner 2 JANUARY 28 CARLISLE SENTINEL cover story out, putting the focus on sec- mon”), the doc who delivered Dan Fogelman’s ‘This Is Us’ is a freshman hit ondary characters and their Kevin and Kate and comes own back stories. Here, in par- back into the picture a decade By Jacqueline Spendlove ticular, we see more into the or so later. TV Media past of Randall’s birth father, Catch up with “This Is Us” William (Ron Cephas Jones, when an episode of the break- f you’re perusing a list of the “Half Nelson,” 2006), and Dr. K out hit airs Tuesday, Jan. 31, Ibest new shows of fall 2016, (Gerald McRaney, “Simon & Si- on NBC. -

Selected Shorts Library’S List of 100 Best Novels

Breakfast of Champions, and Slaughterhouse- Credits Five , which is ranked 18th on The Modern Selected Shorts Library’s list of 100 Best Novels. His other “O Holy Night , or The Year I Ruined Christmas” by Laurie Notaro. From An Idiot Girl’s Christmas works include God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater ; (Villard, 2005). Copyright © 2005 by Laurie Notaro. Used by permission of the Bent Agency. Welcome to the Monkey House ; Deadeye Dick ; Holiday Stories Galapagos ; Hocus Pocus ; and Timequake. “Spirit of Christmas” by Jeanette Winterson. From Christmas Days: 12 Stories and 12 Feasts for Vonnegut was an honorary president of the 12 Days (Grove Press, 2016). Copyright © 2016 by Jeanette Winterson. Used by permission of American Humanist Association until his Peters, Fraser & Dunlop Ltd on behalf of Jeanette Winterson. WHEN: VENUE: death in 2007. SUNDAY, BING DECEMBER 10, 2017 CONCERT HALL “A Present for Big Saint Nick” by Kurt Vonnegut. From Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short 2:30 PM Fiction (Putnam Adult, 1999). First appeared in Argosy (December 1954). Copyright © 1954 by Kurt Vonnegut. Used by permission of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency. Selected Shorts is supported by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, publishers of The Best American Short Stories , edited in 2017 by Meg Wolitzer; The Dungannon Foundation, sponsor of The Rea Award for the Short Story; The Seedlings Foundation; The National Endowment for the Arts; The Henry Nias Foundation; The Axe-Houghton Foundation; and by Symphony Space’s Board of Directors, Producers Circle, and members. The Selected Shorts podcast is sponsored by Zabar’s and Zabars.com. Literature programming at Symphony Space is also made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

Carthage College Computer Science Professor Wins Emmy Award®

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OCTOBER 3, 2019 CONTACT: Brandon Rook, Public Relations Manager [email protected] • Office: 262-551-6686 • Cell: 215-605-6262 CARTHAGE COLLEGE COMPUTER SCIENCE PROFESSOR WINS EMMY AWARD® KENOSHA, Wis. - Carthage College computer science professor Perry Kivolowitz has won a 2019 Engineering Emmy Award for his software SilhouetteFX. This accolade honors an individual, company or organization for innovative developments in broadcast technology. The software has been featured in TV series such as “Game of Thrones,” “Chicago Med,” and “Black Mirror.” "I am extremely pleased and proud that our accomplishments have been recognized in this very prominent way,” Kivolowitz says. “The award comes immediately after the acquisition of SilhouetteFX by another company so in a very real way we're going out with a bang!” SilhouetteFX, a visual effects software co-written by Kivolowitz, provides a comprehensive solution for painting, rotoscoping, and image manipulation of high-resolution image sequences. SilhouetteFX also provides 2D to 3D motion picture conversion. Its fast, scalable, and extensible architecture has resulted in wide adoption in tv programming and motion pictures. The results of SilhouetteFX are designed to be invisible; it is a success when viewers cannot tell that a film has been altered. This isn’t the first time Kivolowitz has been recognized for his contributions to television and movie post-production. Earlier this year, SilhouetteFX received an Academy Award® for Scientific and Technical Achievement ®, after being used in “Avengers Infinity War” and other 2019 Oscar-nominated movies. In 1996, he was also recognized for an Academy Award for Scientific and Technical Achievement for his work with “Forrest Gump” and “Titanic.” In 1992, his contributions to “Babylon 5” also earned him an Emmy Certificate.