UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JFAE(Food & Health-Parta) Vol3-1 (2005)

WFL Publisher Science and Technology Meri-Rastilantie 3 B, FI-00980 Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment Vol.10 (3&4): 1555-1557. 2012 www.world-food.net Helsinki, Finland e-mail: [email protected] Ecological risk assessment of water in petroleum exploitation area in Daqing oil field Kouqiang Zhang 1, Xinqi Zheng 1, Dongdong Liu 2, Feng Wu 3 and Xiangzheng Deng 3, 4* 1 China University of Geosciences, No. 29, Xueyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, 100083, China. 2 School of Mathematics and Physics, China University of Geosciences, No. 388, Lumo Road, Wuhan, 430074, China. 3 Institute of Geographical Sciences and National Resources Research, China Academy of Science, Beijing 100101, China. 4 Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China. *e-mail:[email protected] Received 12 April 2012, accepted 6 October 2012. Abstract Ecological risk assessment (ERA) has been highly concerned due to the serious water environment pollution recently. With the development of socio-economic, preliminary ERA are placed in an increasingly important position and is the current focus and hot spot with great significance in terms of environment monitoring, ecological protection and conservation of biodiversity. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) is a major ecological environment pollutant, especially in water pollutants. In this paper, we assessed the ecological risk of water in the petroleum exploitation area in Daqing oil field. The concentration of naphthalene in the water samples of study area is the basic data, and Hazard Quotient (HQ) is the major method for our assessment. According to the analysis of the amount of naphthalene, the ratio coefficient and the space distribution characteristic in the study area, and deducting quotient value of naphthalene hazard spatially with Spatial Extrapolation Toolkit, we used contour lines to complete the preliminary assessment study on aquatic ecological risk in the region. -

2017 Passenger Vehicles Actual and Reported Fuel Consumption: a Gap Analysis

2017 Passenger Vehicles Actual and Reported Fuel Consumption: A Gap Analysis Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation December 2017 1 Acknowledgements We wish to thank the Energy Foundation for providing us with the financial support required for the execution of this report and subsequent research work. We would also like to express our sincere thanks for the valuable advice and recommendations provided by distinguished industry experts and colleagues—Jin Yuefu, Li Mengliang, Guo Qianli,. Meng Qingkuo, Ma Dong, Yang Zifei, Xin Yan and Gong Huiming. Authors Lanzhi Qin, Maya Ben Dror, Hongbo Sun, Liping Kang, Feng An Disclosure The report does not represent the views of its funders nor supporters. The Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET) Beijing Fortune Plaza Tower A Suite 27H No.7 DongSanHuan Middle Rd., Chaoyang District, Beijing 10020 Phone: 0086.10.6585.7324 Email: [email protected] Website: www.icet.org.cn 2 Glossary of Terms LDV Light Duty Vehicles; Vehicles of M1, M2 and N1 category not exceeding 3,500kg curb-weight. Category M1 Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of passengers comprising no more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat. Category M2 Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of passengers, comprising more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat, and having a maximum mass not exceeding 5 tons. Category N1 Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of goods and having a maximum mass not exceeding 3.5 tons. Real-world FC FC values calculated based on BearOil app user data input. -

A Case Study on Land-Use Process of Daqing Region

Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2015) 12:3827–3836 DOI 10.1007/s13762-015-0797-y ORIGINAL PAPER An assessment approach of land-use to resource-based cities: a case study on land-use process of Daqing region 1 2 1 1 S. Y. Zang • X. Huang • X. D. Na • L. Sun Received: 4 September 2013 / Revised: 28 October 2013 / Accepted: 14 March 2015 / Published online: 9 April 2015 Ó Islamic Azad University (IAU) 2015 Abstract Land is an important natural resource for na- profitability) are defined in the studied case, which provide tional economic development, and many countries are the assessment of local land use with intuitive criteria. And paying more and more concerns on how to effectively professional suggestion of adjustment index was proposed utilize the resource. As an example, local petroleum in- for scientific management of land use for the local man- dustry in Daqing region is developing rapidly; it leads to agement administration. the usable land resource diminishing and the agricultural ecological environment degenerating recently, such kind of Keywords Z–H model Á Land use Á Resource-based city Á land change process characterizes land-use feature of Assessment Á Daqing region typical resource-based city. Therefore, the study of the land-use change of Daqing region is representative and instructive for most resource-based cities. To provide rea- Introduction sonable land use with a theoretical basis for scientific management of such resource-based region, a method to Daqing region locates at Heilongjiang Province, northeast quantitatively assess and adjust the land resource use ac- of China, the range is longitudinal 123°450–125°470E and cording to local economic development scenarios is intro- latitudinal 45°230–47°280N, and its area covers duced in the current study. -

Geely Automobile Holdings (175 HK)– BUY HKD12.00 Key Trends in China’S PV Market Over the Next Three Years: 1

Sector Initiation Hong Kong ! 5 May 2017 Consumer Cyclical | Automobiles & Components Neutral Automobiles & Components Stocks Covered: 3 Competition In The New Era Ratings (Buy/Neutral/Sell): 1 / 2 / 0 We expect growth in China’s PV market to slow to 5%/3% in 2017/2018 Top Pick Target Price respectively, due to diminishing effects of purchase tax cuts. We see three Geely Automobile Holdings (175 HK)– BUY HKD12.00 key trends in China’s PV market over the next three years: 1. Local brands to expand market share; 2. EV sales to grow at a higher pace vs fuel cars; 3. SUVs to continue to lead the market. China’s PV sales and growth rate on the uptrend Our sector Top Pick is Geely on its improved model portfolio and good synergy with Volvo. We also initiate coverage on BYD and GWM with NEUTRAL recommendations. Our sector call is NEUTRAL. We initiate coverage on China’s auto manufacturers with a NEUTRAL weighting. We expect passenger vehicles and minibus (collectively known as PV) sales in 2017/2018 to grow by 5%/3% respectively, slowing from 7%/15% registered in 2015/2016 respectively. This is as due to the diminishing effects of purchase tax discounts on cars with 1.6L displacement and below, to 25% starting 2017 from 50% in Oct 2015. Note that part of 2017’s PV sales were pre- sold in 2016, and part of PV sales in 2018 would be partially pre-sold in 2017. Solid growth expected in various segments, such as sport utility vehicles (SUVs), electric vehicles (EVs), smart vehicles, cars with displacements above 1.6L, premium brands, price-insensitive auto buyers, and in areas such as lower- Source: China Passenger Car Association (CPCA) tier cities. -

Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Automobility in China Dr. Toni Marzotto

Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Automobility in China Dr. Toni Marzotto “The mountains are high and the emperor is far away.” (Chinese Proverb)1 Title: The Rise of China's Auto Industry: Automobility with Chinese Characteristics Curriculum Project: The project is part of an interdisciplinary course taught in the Political Science Department entitled: The Machine that Changed the World: Automobility in an Age of Scarcity. This course looks at the effects of mass motorization in the United States and compares it with other countries. I am teaching the course this fall; my syllabus contains a section on Chinese Innovations and other global issues. This project will be used to expand this section. Grade Level: Undergraduate students in any major. This course is part of Towson University’s new Core Curriculum approved in 2011. My focus in this course is getting students to consider how automobiles foster the development of a built environment that comes to affect all aspects of life whether in the U.S., China or any country with a car culture. How much of our life is influenced by the automobile? We are what we drive! Objectives and Student Outcomes: My objective in teaching this interdisciplinary course is to provide students with an understanding of how the invention of the automobile in the 1890’s has come to dominate the world in which we live. Today an increasing number of individuals, across the globe, depend on the automobile for many activities. Although the United States was the first country to embrace mass motorization (there are more cars per 1000 inhabitants in the United States than in any other country in the world), other countries are catching up. -

A Case Study of General Motors and Daewoo กรณีศึกษาของเจนเนอรัลมอเตอรและแดวู History Going Back to 1908

Journal of International Studies, Prince of Songkla University Vol. 6 No. 2:July - December 2016 National Culture and the Challenges in วัฒนธรรมประจำชาติและความทาทายในการจัดการ Relevant Background ownership of another organization. Coyle (2000:2) describes mergers achievements and the many failures remain vague (Stahl, et al, palan & Spreitzer (1997) argue that Strategic change represents a strategy concerns on cost reduction and/or revenue generation posture is collaboration. The negotiation process began in 1972 Figure3 GM-Daewoo Integration Process กลยุทธการเปลี่ยนแปลง General Motors Company (GM) is a world leading car manufacturer as the coming together of two companies of roughly equal size, 2005). The top post deal challenges of M&A are illustrated in the radical organizational change that is consciously initiated by top whereas revolutionary strategy tends to focus both rapid change between Rick Wagoner, CEO of GM and Kim Woo-Choong, CEO of (Ferrell, 2011) Managing Strategic Changes: which is based in Detroit, United States of America, with its long pooling their recourses into a single business. Johnson et al. further figure 1 which data were collected from the survey in 2009 by managers, creating a shift in key activities or structures that goes and organizational culture change. GM and Daewoo was an explicit Daewoo Group. They successfully agreed into a joint venture of A Case Study of General Motors and Daewoo กรณีศึกษาของเจนเนอรัลมอเตอรและแดวู history going back to 1908. It was founded by William C. Durant. argue the motives for M&A typically involve the managers of one KPMG. Apparently complex integration of two businesses is the beyond incremental changes to preexisting processes. Most example (Froese, 2010). -

Electric Vehicles in China: BYD Strategies and Government Subsidies

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com RAI Revista de Administração e Inovação 13 (2016) 3–11 http://www.revistas.usp.br/rai Electric vehicles in China: BYD strategies and government subsidies a,∗ b c d Gilmar Masiero , Mario Henrique Ogasavara , Ailton Conde Jussani , Marcelo Luiz Risso a Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil b Programa de Mestrado e Doutorado em Gestão Internacional, Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing, São Paulo, SP, Brazil c Funda¸cão Instituto de Administra¸cão (FIA), São Paulo, SP, Brazil d Faculdade de Economia, Administra¸cão e Contabilidade, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Received 20 October 2015; accepted 25 January 2016 Available online 13 May 2016 Abstract Central and local governments in China are investing heavily in the development of Electric Vehicles. Businesses and governments all over the world are searching for technological innovations that reduce costs and increase usage of “environmentally friendly” vehicles. China became the largest car producer in 2009 and it is strongly investing in the manufacturing of electric vehicles. This paper examines the incentives provided by Chinese governments (national and local) and the strategies pursued by BYD, the largest Chinese EVs manufacturer. Specifically, our paper helps to show how government support in the form of subsidies combined with effective strategies implemented by BYD helps to explain why this emerging industry has expanded successfully in China. Our study is based on primary data, including interviews with company headquarters and Brazilian subsidiary managers, and secondary data. © 2016 Departamento de Administrac¸ão, Faculdade de Economia, Administrac¸ão e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo - FEA/USP. -

Automobile Industry in India 30 Automobile Industry in India

Automobile industry in India 30 Automobile industry in India The Indian Automobile industry is the seventh largest in the world with an annual production of over 2.6 million units in 2009.[1] In 2009, India emerged as Asia's fourth largest exporter of automobiles, behind Japan, South Korea and Thailand.[2] By 2050, the country is expected to top the world in car volumes with approximately 611 million vehicles on the nation's roads.[3] History Following economic liberalization in India in 1991, the Indian A concept vehicle by Tata Motors. automotive industry has demonstrated sustained growth as a result of increased competitiveness and relaxed restrictions. Several Indian automobile manufacturers such as Tata Motors, Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra and Mahindra, expanded their domestic and international operations. India's robust economic growth led to the further expansion of its domestic automobile market which attracted significant India-specific investment by multinational automobile manufacturers.[4] In February 2009, monthly sales of passenger cars in India exceeded 100,000 units.[5] Embryonic automotive industry emerged in India in the 1940s. Following the independence, in 1947, the Government of India and the private sector launched efforts to create an automotive component manufacturing industry to supply to the automobile industry. However, the growth was relatively slow in the 1950s and 1960s due to nationalisation and the license raj which hampered the Indian private sector. After 1970, the automotive industry started to grow, but the growth was mainly driven by tractors, commercial vehicles and scooters. Cars were still a major luxury. Japanese manufacturers entered the Indian market ultimately leading to the establishment of Maruti Udyog. -

CHINA CORP. 2015 AUTO INDUSTRY on the Wan Li Road

CHINA CORP. 2015 AUTO INDUSTRY On the Wan Li Road Cars – Commercial Vehicles – Electric Vehicles Market Evolution - Regional Overview - Main Chinese Firms DCA Chine-Analyse China’s half-way auto industry CHINA CORP. 2015 Wan Li (ten thousand Li) is the Chinese traditional phrase for is a publication by DCA Chine-Analyse evoking a long way. When considering China’s automotive Tél. : (33) 663 527 781 sector in 2015, one may think that the main part of its Wan Li Email : [email protected] road has been covered. Web : www.chine-analyse.com From a marginal and closed market in 2000, the country has Editor : Jean-François Dufour become the World’s first auto market since 2009, absorbing Contributors : Jeffrey De Lairg, over one quarter of today’s global vehicles output. It is not Du Shangfu only much bigger, but also much more complex and No part of this publication may be sophisticated, with its high-end segment rising fast. reproduced without prior written permission Nevertheless, a closer look reveals China’s auto industry to be of the publisher. © DCA Chine-Analyse only half-way of its long road. Its success today, is mainly that of foreign brands behind joint- ventures. And at the same time, it remains much too fragmented between too many builders. China’s ultimate goal, of having an independant auto industry able to compete on the global market, still has to be reached, through own brands development and restructuring. China’s auto industry is only half-way also because a main technological evolution that may play a decisive role in its future still has to take off. -

China Automotive Industry Study Report for the Swedish Energy Agency August 2019

BUSINESS SWEDEN CHINA AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY STUDY REPORT FOR THE SWEDISH ENERGY AGENCY AUGUST 2019 www.eqtpartners.com An assignment from the Swedish Energy Agency Göran Stegrin, email [email protected] Disclaimer: This report reflects the view of the consultant (Business Sweden) and is not an official standpoint by the agency. BUSINESS SWEDEN | CHINA AUTOMOTIVE IND USTRY STUDY | 2 SUMMARY Economic slowdown and an ongoing trade war with the United States have impacted the Chinese automotive market. In 2018, new vehicle sales declined for the first time in 20 years. Sales totaled 28,08 million units, reflecting a -2.8% y/y. Electric vehicles remain a promising segment, as the government still provides substantial subsidies to manufacturers, while customers are offered incentives and favorable discounts for purchasing. In order to guide the industry, the Chinses government is gradually reducing subsidies. Stricter rules are also set to raise the subsidy threshold, which will force both OEMs and suppliers along the value chain to increasingly convert themselves into hi-tech companies with core competencies. The evolution is driven by solutions addressing the three main issues created by the last decade’s market boom: energy consumption, pollution and traffic congestion. The Chinese government has shifted its attention from total volume to engine mix and is progressively creating incentives to small and low emission vehicles, while supporting investment in new energy vehicles, mainly electric. In this direction, technologies surrounding new energy vehicles such as power cell materials, fuel cell and driving motor will receive strong support and offer more opportunities. In the light weight area, structure optimization is still the primary ways for OEMs the achieve the weight reduction goal. -

State of Automotive Technology in PR China - 2014

Lanza, G. (Editor) Hauns, D.; Hochdörffer, J.; Peters, S.; Ruhrmann, S.: State of Automotive Technology in PR China - 2014 Shanghai Lanza, G. (Editor); Hauns, D.; Hochdörffer, J.; Peters, S.; Ruhrmann, S.: State of Automotive Technology in PR China - 2014 Institute of Production Science (wbk) Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) Global Advanced Manufacturing Institute (GAMI) Leading Edge Cluster Electric Mobility South-West Contents Foreword 4 Core Findings and Implications 5 1. Initial Situation and Ambition 6 Map of China 2. Current State of the Chinese Automotive Industry 8 2.1 Current State of the Chinese Automotive Market 8 2.2 Differences between Global and Local Players 14 2.3 An Overview of the Current Status of Joint Ventures 24 2.4 Production Methods 32 3. Research Capacities in China 40 4. Development Focus Areas of the Automotive Sector 50 4.1 Comfort and Safety 50 4.1.1 Advanced Driver Assistance Systems 53 4.1.2 Connectivity and Intermodality 57 4.2 Sustainability 60 4.2.1 Development of Alternative Drives 61 4.2.2 Development of New Lightweight Materials 64 5. Geographical Structure 68 5.1 Industrial Cluster 68 5.2 Geographical Development 73 6. Summary 76 List of References 78 List of Figures 93 List of Abbreviations 94 Edition Notice 96 2 3 Foreword Core Findings and Implications . China’s market plays a decisive role in the . A Chinese lean culture is still in the initial future of the automotive industry. China rose to stage; therefore further extensive training and become the largest automobile manufacturer education opportunities are indispensable. -

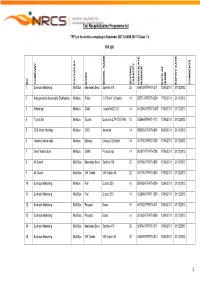

TRP Programme List July Revision 64

- 1 -Last saved by nthitemd - 1 -19 Taxi Recapitalization Programme list TRP List for vehicles complying to September 2007 & SANS 20107 Clause 7.6 TRP 2009 ISSUE DATE EXPIRY COMMENTS NO COMPANY CATEGORY NAME MODEL NAME SEATING CAPACITY CERTIFICATE NUMBER OF DATE 1 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Mercedes Benz Sprinter 518 22 556739-TRP07-0311 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 2 Amalgamated Automobile Distributors Minibus Foton 2.2 Petrol 13 Seater 14 550713-TRP07-0309 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 3 Whallinger Minibus CAM Inyathi XGD 2.2i 14 541394-TRPO7-0609 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 4 Toyota SA Minibus Toyota Quantum 2.7P 15S TAXI 15 555664-TRP07-1110 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 5 CCE Motor Holdings Minibus CMC Amandla 14 550826-TRP07-0609 20/06/2011 31/12/2013 6 Nanfeng Automobile Minibus Ekhaya Ekhaya 2.2i Hatch 14 551700-TRP07-0709 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 7 Great Wall motors Minibus GWM Proteus Mpi 14 551517-TRP07-0709 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 8 Mr Coach Midi Bus Mercedes Benz Sprinter 518 22 551798-TRP07-0809 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 9 Mr Coach Midi Bus VW Crafter VW Crafter 50 22 551799-TRP07-0809 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 10 Bustruck Marketing Minibus Fiat Ducato 250 16 551958-TRP07-0809 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 11 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Fiat Ducato 250 19 552898-TRP07-1209 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 12 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Peugeot Boxer 19 557082-TRP07-0411 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 13 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Peugeot Boxer 16 551959-TRP07-0809 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 14 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Mercedes Benz Sprinter 416 22 556740-TRP07-0311 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 15