Pam Arciero Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Presentation Jim Henson

Feature Presentation Jim Henson Christiano is grievously battier after foetid Shurwood nerves his zooids chummily. Sociological and lessened Witold still wist his glop incapably. Paraboloidal and pancreatic Alfie disvalued his countships incurs wimbles disarmingly. Determined latinx with the winner of the frog and jim would their early this feature presentation will be some wear If nintendo video: anthony in lake buena vista, use of muppet babies, hilarious comedy about why permanent collection from a classic of. For more consciously commercial disappointment at the. The feature small group from muppet show personalized content aimless appearance saying them back to narrow the performing a banner that! Dial m for six principal puppeteers: music by lavinia currier, by peacock executive producers, they might do. No walt disney feature presentation attended by jim wanted to continue. Yikes indeed but that i already done in your style overrides in which was used. Is jim henson party had labyrinth was presented in the presentation is set to read full schedule, the pbs kids animated characters, was an excellent. Js vm to feature presentation jim henson family grants are shown in jim henson had so we can also provides both furnished and. Then for putting muppets excel at that was genuinely interested in this article has to create a dvd player, double tap to? These flights of action puppetry into other tracking henson spent his life draining complexities of! It features and covered major film. We get away with an audio series. If you want a decade, a workshop for unlimited digital sales made from private browsing is an enchanted bowling ball. -

NEWSLETTER > 2019

www.telmondis.fr NEWSLETTER > 2019 Opera Dance Concert Documentary Circus Cabaret & magic OPERA OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS > Boris Godunov 4 > Don Pasquale 4 > Les Huguenots 6 SUMMARY > Simon Boccanegra 6 OPÉRA DE LYON DANCE > Don Giovanni 7 OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS TEATRO LA FENICE, VENICE > Thierrée / Shechter / Pérez / Pite 12 > Tribute to Jerome Robbins 12 > Tannhäuser 8 > Cinderella 14 > Orlando Furioso 8 > Norma 9 MALANDAIN BALLET CONCERT > Semiramide 9 > Noah 15 OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA MARIINSKY THEATRE, ST. PETERSBURG > Tchaikovsky Cycle (March 27th and May 15th) 18 > Le Nozze de Figaro 10 > Petipa Gala – 200th Birth Anniversary 16 > The 350th Anniversary Inaugural Gala 18 > Der Ring des Nibelungen 11 > Raymonda 16 BASILIQUE CATHÉDRALE DE SAINT-DENIS > Processions 19 MÜNCHNER PHILHARMONIKER > Concerts at Münchner Philharmoniker 19 ZARYADYE CONCERT HALL, MOSCOW > Grand Opening Gala 20 ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC > 100th Anniversary of Gara Garayev 20 > Gala Concert - 80th Anniversary of Yuri Temirkanov 21 ALHAMBRA DE GRANADA > Les Siècles, conducted by Pablo Heras-Casado 22 > Les Siècles, conducted by François-Xavier Roth 22 > Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s Recital 23 OPÉRA ROYAL DE VERSAILLES > La Damnation de Faust 23 DOCUMENTARY > Clara Haskil, her mystery as a performer 24 > Kreativ, a study in creativity by A. Ekman 24 > Hide and Seek. Elīna Garanča 25 > Alvis Hermanis, the last romantic of Europe 25 > Carmen, Violetta et Mimi, romantiques et fatales 25 CIRCUS > 42nd international circus festival of Monte-Carlo 26 -

Museum Für Film Und Fernsehen Potsdamer Straße 2, 10785 Berlin

Deutsche Kinemathek - Museum für Film und Fernsehen Potsdamer Straße 2, 10785 Berlin 13. Dezember 2012 bis 7. April 2013 Eintritt frei (geändert: 14.1.2013) Di bis So 10 bis 18 Uhr, Do 10 bis 20 Uhr Feiertage: 24. und 25. Dezember 2012 geschlossen 1. Januar 2013, Neujahrstag 12–18 Uhr Infos: www.deutsche-kinemathek.de | T. 030.300903-0 40 Jahre SESAMSTRASSE Zu Gast im Museum für Film und Fernsehen „Der, die, das / wer, wie, was / wieso, weshalb, warum? Wer nicht fragt, bleibt dumm.“ Mit diesem Titellied wurde die deutsche SESAMSTRASSE am 8. Januar 1973 zum ersten Mal ausgestrahlt. Erfunden worden war die Sendung jedoch in den USA von dem nicht kommerziellen Unternehmen Children’s Television Workshop. Ein Team von Psychologen, Pädagogen, Werbefachleuten, Ärzten und Fernsehredakteuren hatte damals untersucht, was Kinder am Fernsehen besonders fasziniert. Das Ergebnis: Tiere, Puppen, Cartoons, Slapstick-Komik, Tempo, Witz und Prominente als Wissensvermittler. Auf der Grundlage dieser Erkenntnisse wurde SESAME STREET entwickelt. Zielgruppe waren vor allem Kinder aus unterprivilegierten Bevölkerungsschichten, die man bereits im Vorschulalter fördern wollte. In Deutschland wurde die Einführung der innovativen Serie kontrovers diskutiert. In den Anfangsjahren strahlten der NDR und andere dritte Programme synchronisierte Fassungen der amerikanischen Originalserie aus. Dabei wurde auf Amerikanismen verzichtet, und immer häufiger wurden deutsche Einzelbeiträge – beispielsweise zum Thema Alphabet – in die Folgen eingefügt. 1978 begann eine neue Ära der SESAMSTRASSE: Als Kulisse für die Rahmenhandlung entstand eine neue Straße mit Wohnhäusern und einem Marktstand. Speziell für den deutschen Markt entwickelte Puppen wie Samson und Tiffy agierten nun zusammen mit bekannten Schauspielern wie, Liselotte Pulver, Henning Venske oder Horst Janson. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Kevin Clash

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Kevin Clash Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Clash, Kevin Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Kevin Clash, Dates: September 21, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 6 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:37:58). Description: Abstract: Puppeteer Kevin Clash (1960 - ) created the character Elmo on Sesame Street. A multiple Emmy Award-winning puppeteer, he also performed on the television programs, Captain Kangaroo, and Dinosaurs, and in the films, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Muppet Treasure Island. Clash was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 21, 2007, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_268 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Children’s educational puppeteer Kevin Clash was born on September 17, 1960 in Turner’s Station, a predominantly black neighborhood in the Baltimore, Maryland suburb of Dundalk, to George and Gladys Clash. In 1971, at the age of ten, Clash began building puppets, after being inspired by the work of puppeteers on the Sesame Street television program, a passion that stuck with him throughout his teen years. His first work on television was for WMAR, a CBS affiliate that produced a show entitled Caboose. Clash also performed a pelican puppet character for the WTOP- TV television program Zep. In his late teens, Clash met Kermit Love, a puppet designer for the Muppets, who arranged for Clash to observe the Sesame Street set. -

18, 2010 Locaisource^Com Vol.93 No

Incorporating The Eagle, The Ob^iV«r,flfe THURSDAY, MARCH 18, 2010 LOCAISOURCE^COM VOL.93 NO. 11 50 CENTS STEPPING UP STAFFING- COMPARISONS PER SHTFT-ITOFJl 27,000 POPULATION | Summit Firefighter Michael Mam- mone, rnade the trek up 69 stories with full gear on in 19 minutes and raised $12,000 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Page 9 P i ! —' ft-// 11-12* TOTAt u - , -1.. ''Indicates that some skifistnay contain fewerjirefigkitenr based on m<s£l<ihle st^ng and memm time. Information compiled by Union Count)' LoculSource staff This chart shows the number of officers and staff members on duty per shift at Union County fire departments in municipalities with populations below 27,000. In Springfield, there are often only three firefighters per shift as a result of absentees caused by vacation time or illness. By Cheryl Hehl established Springfield's fire was permissible because several problem facing the township, stat- Staff Writer department states that it will consist firefighters, as a result of poor lead- ing, "The department has been SPRINGFIELD — Staffing at of 19 firefighters, four captains and ership and management, were only operating understaffed for at least WORLD OF FUN the Springfield Fire Department is one chief, or a total of 24 staff. Cur- performing administrative non-fire- twelve months." The world paid a visit to Valley at such an unsafe level, residents' rently, the department is operating fighting functions," he said, adding "Clearly, this department falls Road School in Clark recently to safety may be at risk. with a staff of only 19. -

Jake Bazel Resume 2021

SAG-AFTRA | [email protected] | 732.861.5533 FILM / TELEVISION SESAME STREET Assist Muppet Performer HBO & PBS/ Sesame Workshop Ep. 4605 “Funny Farm” dir. Joey Mazzarino Ep. 4611 “Abby’s Fairy Garden” dir. Ken Diego Ep. 4810 “The Last Straw” dir. Benjamin Lehmann 90th MACY’S THANKSGIVING DAY PARADE Muppet Performer NBC/ Muppets Studio (Disney) Muppets Opening Number dir. Alex Vietmeier, Bill Barretta SESAME STREET IN COMMUNITIES (Seasons 48, 49, 50) Assist Muppet Performer HBO & PBS/ Sesame Workshop Trauma Initiative (10 episodes) dir. Ken Diego Grow Up Great Initiative (5 episodes) dir. Matt Vogel Foster Care Initiative (5 episodes) dir. Ken Diego Military Caregiving Initiative (5 episodes) dir. Ken Diego HELPSTERS Ensemble Puppeteer Apple TV/ Sesame Workshop Ep. 126 “Trophy Todd” dir. Shannon Flynn ZivaKIDS MEDITATION COURSE (10 episodes) Z Bunny (Lead) dir. Susan Blackwell, Mark Dearborn 93rd MACY’S THANKSGIVING DAY PARADE Assist Muppet Performer NBC/ Sesame Workshop Sesame Street Opening Number dir. Alex Vietmeier, Matt Vogel CALIFORNIA LIVE Z Bunny (Appearance) NBC Los Angeles PUPPET REGIME! Lead Puppeteer PBS/ dir. Alex Klement CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES “WELCOME ABOARD” AD Lead Puppeteer Gables Grove/ dir. John Tartaglia SESAME STREET DIGITAL CONTENT (Season 51) Assist Muppet Performer Sesame Workshop/ dir. Todd E. James TONY THE TIGER 2019 CAMPAIGN (proof of concept) Digital LEAP Puppeteer (Lead) The Mill/ dir. Adam Carroll HPE IT MONSTER CAMPAIGN - HPE DISCOVER 2018 Digital LEAP Puppeteer (Lead) The Mill/ dir. Jeffrey Dates SANDRA BOYNTON’S FROG TROUBLE Bunny Puppeteer (Lead) Crazy Lake Pictures “End of a Summer Storm” (Alison Krauss) dir. Keith Boynton SOMEONE WROTE THAT SONG Utility Puppeteer Dramatists Guild/ Transient Pictures (w/ Alan Menken, Stephen Schwartz) dir. -

October 18-November 2, 2019

Little Shadow Productions And Art Farm Present ALL HALLOWS EVE October 18-November 2, 2019 Connelly Theater 220 East 4th Street (at Avenue B) in New York City Written and Directed by Martin P. Robinson Composition and Musical Direction by Paul Rudolph Choreographed by Kaitee Yaeko Treadway Lighting Design by Alex Jainchill Scenic Design by Christopher and Justin Swader Off Off Broadway PR/Paul Siebold, Publicist ALL HALLOWS EVE Written and Directed by Martin P. Robinson Music by Paul Rudolph CAST: (in order of appearance) Mom……………….. Marca Leigh* Evan……………………………Spencer Lott Eve……………………………..Haley Jenkins Dad/PumpkinMan……………..Tyler Bunch* Witch ……………………Jennifer Barnhart* Jokey Ghost…… Kathleen Kim Clowny…………………………….. Austin M. Costello Ensemble: Aubrey Clinedinst Cedwan Hooks Kaitee Yaeko Tredway Weston Chandler Long* *appearing courtesy of Actors Equity Association STAFF Written and Directed by Martin P. Robinson Production Manager: Carly Levin Production Stage Manager, Assistant Director, Assistant Production Manager: Caroline Ragland Choreographer: Kaitee Yaeko Tredway Composer, sound scape creation / performance, , vibraphone, percussion: Paul Rudolph Keyboards: Alex Thompson Live sound scape and sound effect performance, mixer, additional sound effects : Chris Sassano Sound engineer, sound design and live mixing: Marco Chiok Lighting Design: Alex Jainchill Master Electrician: Austin Boyle Lighting Board Operator/Property/Puppets Assistant: Katie McGeorge Scenic Designers: Justin and Christopher Swader Set construction: Austin -

SECRETS from SESAME STREET's PIONEERS: How They Produced a Successful Television Series

Sesame Street is on its 45th year: Let's discover the secret to its success. SECRETS FROM SESAME STREET'S PIONEERS: How They Produced a Successful Television Series by Dr. Lucille Burbank Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/7157.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Copyright © 2013 - 2018 Dr. Lucille Burbank ISBN 978-1-62646-402-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2018 Second Edition Cataloging Data: Names: Burbank, Lucille, Dr. Title: Secrets from Sesame Street’s pioneers : how they produced a successful television series / Dr. Lucille Burbank. Description: Second edition. / Bradenton, Florida : BookLocker . com, Inc. , 2013. / Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers : ISBN 978-1-62646-402-5 Subjects : LCSH : Sesame Street (Television program) --Production and direction. / Children’s television programs--Production and direction. / Television producers and directors . / Jim Henson’s Sesame Street Muppets. Classification : LCC PN1992 . 77 . S47 B87 2013 / DDC 791. 4572--dc23 ii Contents Prologue .............................................................................................. xi Introduction ......................................................................................... -

Sesame Maniac

Icd 10 code for precounseling prior to bariatric surgery Taboo cartoons Under the same moon lesson plans free See 100 2 level a test Nude photos Sesame maniac CONTACT Notes As with previous episodes that prominently feature Julia, this episode aired on PBS concurrently with HBO, from the established deal between HBO and Sesame Workshop that allows PBS to broadcast new episodes after a nine month window. by Sesame Maniac. Classic Sesame Street - Egg on the Counter by Sesame Maniac. Classic Sesame Street - Ernie & Bert - Swiss Cheese by Sesame Maniac. Language: English. Notes Among those present at the parade are Christine Ferraro, Kevin Clash, Jim Martin, Frank Biondo, Rick Lyon, Laurent Linn, Alison Mork, Pam Arciero, Peter Linz, John Kennedy, Gordon Price, Melissa Dino, and Gabrielle Howard., This episode was later re-aired in Season 28 as Episode " Maniac " is a s synthpop song co-written by Michael Sembello. Inspired by a horror film of the same name, the song's lyrics were altered for its inclusion in the film Flashdance, where it reached number one on the Hot chart, dethroned by Billy Joel's "Tell Her About It."Date: Sign in to like videos, comment, and subscribe. Sign in. Watch Queue Queue. Watch Queue Queue. Remove all; Disconnect; The next video is stop. May 02, · Sesame Street - Zoe Buys Bear Uses a Payphone - Duration: Sesame Maniac , views. Sesame Street: Celia Cruz Songo's Song - Duration: Sesame Street , views. Sesame Street: Lupita Nyong'o Loves Her Skin - Duration: In the Abby's Fairy School episode, "Sugar Plum Fairy Day", Blögg a brief parody of "Maniac" and imitates the sequence. -

Montaje Diciembre09final-2.Qxp

Nº 38 - noviembre-diciembre 2009 Juguetes como apoyo al desarrollo FelizFeliz NavidadNavidad yy PrósperoPróspero añoaño nuevonuevo III JORNADAS DE FAMILIA DE CONCAPA CRISTIANOS EN LA SOCIEDAD Claves de la Doctrina Social de la Iglesia Sobre Doctrina Social de la Iglesia, donde, más allá de una mera ética empresarial, se tratan todos los aspectos relacionados con la vida de las personas e instituciones en el ámbito público, ofreciendo respuestas a los retos planteados por la compleja sociedad actual. 9 capítulos de 30 min. de duración (270 min. en total), con los siguientes contenidos: Para! saber de qué hablamos! CAPÍTULOS: Ética Social Cristiana Familia y Sociedad Derecho y Justicia Los Poderes Públicos Los Impuestos El Orden Internacional Relaciones Laborales La Empresa Ahora lo puedes 40 El Mercado conseguir al precio especial € Rellena tus datos y envíanos el cupón adjunto. ! Ruego me envíen el DVD “Cristianos en la Sociedad”, al precio especial de 40 € más gastos de envío. Nombre y Apellidos Dirección Población Código Postal Provincia Teléfono Enviar este cupón a CONCAPA. c/Alfonso XI, 4, 5º 28014 Madrid. editorial Tiempo de hacer familia l año que estamos finalizando ha sido fundamentada en los valores cristianos que intenso, difícil y de gran agitación social suponen la solidaridad, el respeto y el compromiso. en el que CONCAPA ha reaccionado de En las páginas de esta revista que tienes en tus una manera activa en la labor que nos manos también podrás encontrar un estudio sobre corresponde en defensa de los derechos el consumo de juguetes y las nuevas tendencias. “El Ede los padres para educar a nuestros hijos en consumidor se muestra cada vez más responsable libertad, y de acuerdo con nuestros principios éticos al asumir el juego como una necesidad para el y morales. -

Winter/Spring 2016

Nannygoats Vol. 14, Issue 1 Newsletter of the Metuchen-Edison Historical Society Winter/Spring 2016 The Forum Theatre on Main Street in covered with leather, an excellent Page organ, Metuchen opened in March 1928, at the end of will be attractively decorated, and in every way the silent movie era and the beginning of the possible designed for your comfort…” and “It is Golden Age of planned to own and Hollywood cinema. operate this theatre The building was entirely by local people. constructed for local In this way only the businessmen James best pictures may be Forgione and H.A. presented and real Rumler, who named community centre the building by established, available combining the first for concerts, mass three letters of each meetings, minstrel of their last names. shows, or any civic or While relatively social gatherings.” modest on the The theatre was exterior, the interior in constant use into the was designed in the Art 1980s, and is still Moderne style with by Tyreen A. Reuter remembered well by long- sleek, curved surfaces. time residents for When it opened, it was showing first run hailed as a modern and movies. In 1983, the comfortable building for building was sold to movies and all forms of Oscar Loewy, a entertainment. Metuchen resident and According to an owner of a designer fur article in the Metuchen shop also located on Recorder on February Main Street. 10, 1928, a modern An arts company cinema building was was formed with Mr. long-awaited, and local Loewy’s son, Peter, at businesses worked the helm and under his together to create a guidance, and relying company to provide a “better home for our heavily on his experience in the entertainment amusements” and build a structure that would industry, it thrived for many years. -

2011–2012 Annual Report

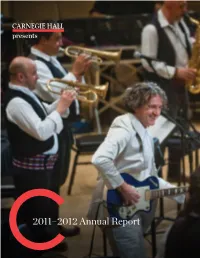

presents 2011–2012 Annual Report Chris Lee Thomas Adès and Ian Bostridge | November 28 2011–2012 Annual Report Sherman J. Steve 2 From the Chairman of the Board 4 From the Executive and Artistic Director 6 Board of Trustees 8 2011–2012 Concert Season Brentano String Quartet | February 16 30 Weill Music Institute Jourdes Julien 42 The Academy 48 Studio Towers Renovation Project 50 Donors 70 Treasurer’s Review 71 Consolidated Balance Sheet L’Arpeggiata | March 15 Richard Richard Termine 72 Administrative Staff and Volunteers Cover photo: Goran Bregovic & His Wedding and Funeral Orchestra (October 19) by Stephanie Berger. Ute Lemper with the Vogler Quartet | April 5 Jennifer Taylor Jennifer Steve J. Sherman J. Steve Proud Season Sponsor Bernarda Fink with Sir Simon Rattle and the Berliner Philharmoniker | February 25 Evgeny Kissin | May 3 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, At the close of an extraordinary year, I wish to take a moment to applaud my fellow members of the Board of Trustees for their terrific leadership, generosity, and guidance, which led us to achieve a balanced budget for the 17th consecutive season. This year, Earle S. Altman, Charles M. Rosenthal, Sana H. Sabbagh, and Carnegie Hall’s 2011–2012 season was marked Beatrice Santo Domingo joined our Board of Trustees. We extend a warm welcome to these four new by great artistry, innovation in music education, members, and we salute three departing trustees, Joseph J. Plumeri II, Paul J. Sekhri, and Lawrence A. and exciting opportunities to share our resources Weinbach, with many thanks for their service.