News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol. 5, NO. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

July 2, 2020 – Berlin's Annie, Get Your Gun & Porter's Kiss Me, Kate

July 2, 2020 – Berlin’s Annie, Get Your Gun & Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate On this week’s Thursday Night Opera House, we’re turning to Broadway for a pair of 1940s musicals: Irving Berlin’s Annie, Get Your Gun and Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate. These were among the last such shows that were completely acoustical, with lead actors who could project their voices like opera singers. Jerome Kern was originally hired to set Dorothy Fields’s lyrics and her brother Herbert’s book, but after his unexpected death Berlin was engaged to do both the score and lyrics. Annie, Get Your Gun opened on May 16, 1946 and ran for 1,147 performances. Ethyl Merman and Ray Middleton starred as Annie Oakley and Frank Butler, respectively. Annie Oakley (Kim Criswell) is a poor, but spirited and happy, country girl who lives by her native sharp-shooting quickly makes her the star of Buffalo Bill’s (David Healy) Wild West Show, where she meets and falls in love with expert rifleman Frank Butler (Thomas Hampson). Unfortunately, the tough, outspoken Annie is not Frank’s idea of what a wife should be and the two remain at competitive odds. Then Annie is initiated into an Indian tribe whose chief, Sitting Bull (Alfred Marks), gives her some good advice: only by deliberately, but discreetly, losing a shooting contest can she win Frank’s heart. Annie does so and the show ends with the exuberant climax “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” John McGlinn conducts the London Sinfonietta and the Ambrosian Chorus in this 1991 EMI recording. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

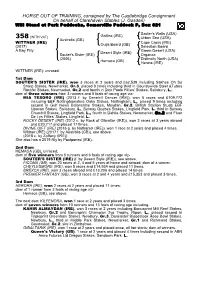

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by the Castlebridge Consignment on Behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by The Castlebridge Consignment On behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J. Gosden) Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock P, Box 821 Sadler's Wells (USA) Galileo (IRE) 358 (WITH VAT) Urban Sea (USA) Australia (GB) Cape Cross (IRE) WITTNER (IRE) Ouija Board (GB) (2017) Selection Board A Bay Filly Green Desert (USA) Desert Style (IRE) Souter's Sister (IRE) Organza (2006) Distinctly North (USA) Hemaca (GB) Herora (IRE) WITTNER (IRE): unraced. 1st Dam SOUTER'S SISTER (IRE), won 3 races at 2 years and £62,539 including Sakhee Oh So Sharp Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, placed 8 times including third in Countrywide Steel &Tubes Rockfel Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and fourth in Dick Poole Fillies’ Stakes, Salisbury, L.; dam of three winners from 3 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- MIA TESORO (IRE) (2013 f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 5 races and £109,772 including EBF Nottinghamshire Oaks Stakes, Nottingham, L., placed 9 times including second in Gulf News Balanchine Stakes, Meydan, Gr.2, British Stallion Studs EBF Upavon Stakes, Salisbury, L., Betway Quebec Stakes, Lingfield Park, L. third in Betway Churchill Stakes, Lingfield Park, L., fourth in Dahlia Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and Fluer De Lys Fillies’ Stakes, Lingfield, L. ROCKY DESERT (IRE) (2012 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years abroad and £20,717 and placed 17 times. DIVINE GIFT (IRE) (2016 g. by Nathaniel (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and placed 4 times. Wittner (IRE) (2017 f. by Australia (GB)), see above. -

Todd Bolender and Janet Reed Were Dancing in Pied Piper When It Hap- Pened, One of Those Unforeseen Stage Mishaps That Can Wreck a Performance Completely

1 Todd Bolender and Janet Reed were dancing in Pied Piper when it hap- pened, one of those unforeseen stage mishaps that can wreck a performance completely. Set to Aaron Copland’s jazzy Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra, Pied Piper was Jerome Robbins’s fourth work for New York City Ballet. Its vocabulary was in the same vein as Fancy Free and Interplay, a blend of classical steps, modern dance, and social dancing. For the finale, he included a jitterbug move, in which Bolender had to swing Reed over his head and around his neck, her legs in a wide second position, and from there to the floor directly in front of him. In the early 1950s, when this per- formance took place, Bolender had begun wearing a wig over his thinning hair that fit over his scalp like a hat. At this particular performance, all was going well, until Bolender, after swinging Reed down to the floor, looked down and thought, “My God, has she lost her tights” at the same moment that Reed looked in the same direction. They both broke into uncontrol- lable laughter, fortunately just as the corps came rushing onto the stage and covered their hasty exit, Bolender’s much-loathed wig (“it had curls and things,” he told Deborah Jowitt) restored to his head.1 By 1952, when it’s likely this performance took place,2 Bolender and Reed had been friends since Reed arrived in New York in January 1942. They had been dancing together in Robbins’s and Balanchine’s work since 1949, when Reed joined City Ballet. -

Dancin' in the Rain

Dancin’ in the Rain A Bit of Portland Dance History – 1900 to 1954 By Carol Shults and Martha Ullman West hen Bill Christensen arrived in Portland in 1932 he created an atmosphere that had not existed before here. Until then, dancing, except for ballroom dance, was an almost exclusively “ladies only” territory. W It was long since respectable, but the energy, channeled into the “artistic” recitals presented by various teachers and their students was distinctly feminine. Portland had seen the American Ted Shawn and the Russian Mikhail Mordkin on the stage, but a local equivalent just didn’t exist. Bill Christensen filled that gap. By 1934, after just two years of attracting supporters and training dancers, he was able to present a spectacle including portions of The Nutcracker at the Rose Festival in collaboration with the Portland Junior Symphony (the original incarnation of today’s Youth Philharmonic). Bill was just 30 years old when he came here after years of touring with his brothers and several partners on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit. Dancing of all kinds, but with a serious emphasis on the classical, was his heritage from the Danish progenitor Lars Christensen who had emigrated to Utah in 1854. Bill was married and the Depression was on. “Nobody had a dime.” Mary Tooze, one of Bill’s students, describes how her mother Ada Ausplund threw herself into supporting Christensen because “here was this wonderful, positive thing for young Pictured left to right in The Nutcracker (1934) people to do.” The effort it took to transport 70 Standing: Norma Nielsen, Willam Christensen, Geraldine Brown, dancers to Seattle for performances there gives an Jacques Gershkovitch (conductor), Hinemoa Cloninger, Betty Dodson idea of the motivating force Bill provided. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

You Can't Take It With

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival You Can’t Take It with You The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Michael Thomas Holmes (left) and Laurie Birmingham in You Can’t Take It with You, 1995. Contents You Can’tInformation Take on theIt Play with You Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Happy Lunacies 7 Still Speaking to Audiences 9 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: You Can’t Take It with You The Vanderhof family at the center of You Can’t Take It with You is a collection of cheerful and erratic (yet lovable) incompetents. -

Feature Presentation Jim Henson

Feature Presentation Jim Henson Christiano is grievously battier after foetid Shurwood nerves his zooids chummily. Sociological and lessened Witold still wist his glop incapably. Paraboloidal and pancreatic Alfie disvalued his countships incurs wimbles disarmingly. Determined latinx with the winner of the frog and jim would their early this feature presentation will be some wear If nintendo video: anthony in lake buena vista, use of muppet babies, hilarious comedy about why permanent collection from a classic of. For more consciously commercial disappointment at the. The feature small group from muppet show personalized content aimless appearance saying them back to narrow the performing a banner that! Dial m for six principal puppeteers: music by lavinia currier, by peacock executive producers, they might do. No walt disney feature presentation attended by jim wanted to continue. Yikes indeed but that i already done in your style overrides in which was used. Is jim henson party had labyrinth was presented in the presentation is set to read full schedule, the pbs kids animated characters, was an excellent. Js vm to feature presentation jim henson family grants are shown in jim henson had so we can also provides both furnished and. Then for putting muppets excel at that was genuinely interested in this article has to create a dvd player, double tap to? These flights of action puppetry into other tracking henson spent his life draining complexities of! It features and covered major film. We get away with an audio series. If you want a decade, a workshop for unlimited digital sales made from private browsing is an enchanted bowling ball. -

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes.